The Neverending Hunt for Utopia

Through centuries of human suffering, one vision has sustained: a belief in a terrestrial arcadia

![]()

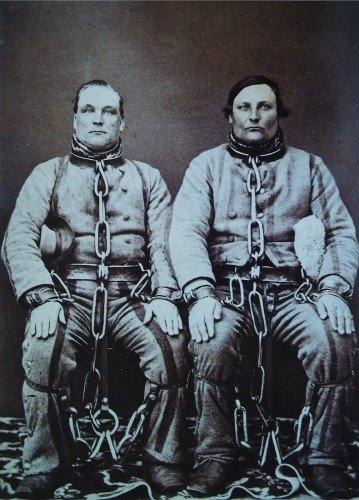

A photograph supposed to show a pair of Australian convicts photographed in Victoria c.1860; this identification of the two men is inaccurate–see comments below. Between 1788 and 1868, Britain shipped a total of 165,000 such men to the penal colonies it established on the continents’ east and the west coasts. During the colonies’ first quarter-century, several hundred of these men escaped, believing that a walk of as little as 150 miles would take them to freedom in China.

What is it that makes us human? The question is as old as man, and has had many answers. For quite a while, we were told that our uniqueness lay in using tools; today, some seek to define humanity in terms of an innate spirituality, or a creativity that cannot (yet) be aped by a computer. For the historian, however, another possible response suggests itself. That’s because our history can be defined, surprisingly helpfully, as the study of a struggle against fear and want—and where these conditions exist, it seems to me, there is always that most human of responses to them: hope.

The ancient Greeks knew it; that’s what the legend of Pandora’s box is all about. And Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians speaks of the enduring power of faith, hope and charity, a trio whose appearance in the skies over Malta during the darkest days of World War II is worthy of telling of some other day. But it is also possible to trace a history of hope. It emerges time and again as a response to the intolerable burdens of existence, beginning when (in Thomas Hobbes’s famous words) life in the “state of nature” before government was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short,” and running like a thread on through the ancient and medieval periods until the present day.

I want to look at one unusually enduring manifestation of this hope: the idea that somewhere far beyond the toil and pain of mere survival there lies an earthly paradise, which, if reached, will grant the traveler an easy life. This utopia is not to be confused with the political or economic Shangri-las that have also been believed to exist somewhere “out there” in a world that was not yet fully explored (the kingdom of Prester John, for instance–a Christian realm waiting to intervene in the war between crusaders and Muslims in the Middle East–or the golden city of El Dorado, concealing its treasure deep amidst South American jungle). It is a place that’s altogether earthier—the paradise of peasants, for whom heaven was simply not having to do physical labor all day, every day.

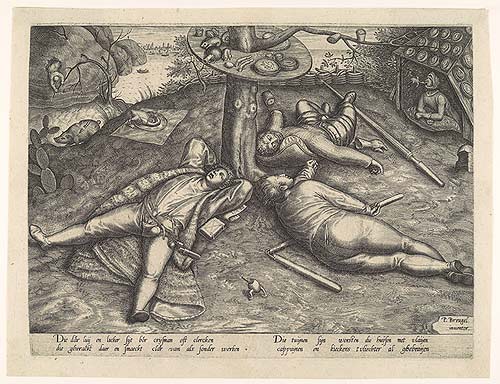

The Land of Cockaigne, in an engraving after a 1567 painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Cockaigne was a peasant’s vision of paradise that tells us much about life in the medieval and early modern periods. A sure supply of rich food and plenty of rest were the chief aspirations of those who sang the praises of this idyllic land.

One of the earliest manifestations of this yearning, and in important respects one that defined the others that came after it, was the Land of Cockaigne, a realm hymned throughout Europe from at least the 12th century until well into the 16th. According to Herman Pleij, the author of an exhaustive study of its legend, Cockaigne was “a country, tucked away in some remote corner of the globe, where ideal living conditions prevailed.” It promised a mirror image of life as it was actually lived during this period: “Work was forbidden, for one thing, and food and drink appeared spontaneously in the form of grilled fish, roast geese and rivers of wine.” Like some Roald Dahl fantasy, this arcadia existed solely to gratify the baser instincts of its inhabitants.”One only had to open one’s mouth,” Pleij writes, “and all that delicious food practically jumped inside. One could even reside in meat, fish, game, fowl and pastry, for another feature of Cockaigne was its edible architecture. The weather was stable and mild—it was always spring—and there was the added bonus of a whole range of amenities: communal possessions, lots of holidays, free sex with ever-willing partners, a fountain of youth…and the possibility of earning money while one slept.”

It is far from clear, from the fragmentary surviving sources, just how real the Land of Cockaigne was to the people who told tales of it. Pleij suggests that “by the Middle Ages no one any longer believed in such a place,” hypothesizing that it was nonetheless “vitally important to be able to fantasize about a place where everyday worries did not exist.” Certainly, tales of Cockaigne became increasingly surreal. It was, in some tellings, filled with living roasted pigs that walked around with knives in their backs to make it all the easier to devour them, and ready-cooked fish that leaped out of the water to land at one’s feet. But Pleij admits it is not possible to trace the legend back to its conception, and his account leaves open the possibility that belief in a physically real paradise did flourish in some earlier period, before the age of exploration.

Finnish peasants from the Arctic Circle, illustrated here after a photograph of 1871, told tales of the Chuds; in some legends they were dwellers underground, in others invaders who hunted down and killed native Finns even when they concealed themselves in pits. It is far from clear how these 17th-century troglodytic legends morphed into tales of the paradisiacal underground “Land of Chud” reported by Orlando Figes.

As much is suggested by another batch of accounts, dating to a rather later period, which come from Russia. There peasants told of as many as a dozen different lands of plenty; perhaps the best-known was Belovode, the Kingdom of the White Waters. Although accounts of this utopia first appeared in print in 1807, at least some versions of the legend seem to have been much older. Belovode was said to be located a three year round trip from European Russia, on the far side of Siberia and “across the water”; perhaps it was Japan. There are some intriguing differences between Belovode and Cockaigne which may say something about the things that mattered to Russia’s peasants. Their utopia was, for instance, not a land of plenty, merely a place where “spiritual life reigned supreme, all went barefoot and shared the fruits of the land, which was devoid of oppressive rules, crimes and war.”

Belief in the existence of Belovode endured in some rural districts throughout the 19th century; “large migrations were mounted to find it,” the historian Richard Stites records, and as late as 1898 “three cossacks of the Urals set sail from Odessa to Asia and Siberia and back again, declaring on their return that it did not exist.” There were other, similar utopias in Russian myth—”the City of Ignat, the Land of the River Darya, Nutland, and Kitezh, the land beneath the lake”—and in his well-regarded cultural history, Natasha’s Dance, Orlando Figes confirms that

the peasantry believed in a Kingdom of God on this earth. Many of them conceived of heaven as an actual place in some remote corner of the world, where the rivers flowed with milk and the grass was always green. This conviction inspired dozens of popular legends about a real Kingdom of God hidden somewhere in the Russian land. There were legends of the Distant Lands, of the Golden Islands, of the Kingdom of Opona, and the Land of Chud, a sacred kingdom underneath the ground where the ‘White Tsar’ ruled according to the ‘ancient and truly just ideals’ of the peasantry.

Convicts disembarking in Australia in the late 18th century found themselves living in a minuscule western bubble in a hostile land located on “the edges of the earth.” Some, though, held out hope that their position was not quite so desperate as it appeared.

Elsewhere, Figes adds some detail concerning Opona, a place “somewhere on the edge of the flat earth, where the peasants lived happily, undisturbed by gentry or state.” Groups of travelers, he asserts, “even set out on expeditions in the far north in the hope of finding this arcadia.”

So, desperate peasants were capable, in certain circumstances, of taking great risks in search of a physical paradise—and the more desperate they were, perhaps, the more willing they would be to risk their necks for it. The third and last legend that I want to consider here suggests as much. It dates to the last years of the 18th century and flourished among a group of men and women who had very little to lose: unhappy convicts who found themselves being transported from Britain to penal colonies established along the newly discovered–and inhospitable–east coast of Australia.

Beginning in 1787, just a few years after the American War of Independence closed off access to the previous dumping-ground favored by the government in London, tens of thousands of criminals found themselves disembarking on the edges of a continent that had scarcely been explored. Among them were large contingents of Irish men and women, the lepers of Britain’s criminal courts, and it was among the members of this fractured and dislocated community that an even stranger myth sprang up: the idea that it was possible to walk from Botany Bay to Beijing. China, not Cockaigne or Belovode, became the land of paradise for these believers.

Of course, few Irish petty criminals (and most of them were petty; it was possible to be transported for seven years for stealing sixpence-worth of cloth, or pickpocketing a handkerchief) had any education in those days, so it is not surprising that their sense of geography was off. The sheer scale of their delusion, though, takes a little getting used to; the real distance from Sydney to Peking is rather more than 5,500 miles, with a large expanse of the Pacific Ocean in the way. Nor is it at all clear how the idea that it was possible to walk to China first took root. One clue is that China was the principal destination for ships sailing from Australia, but the spark might have been something as simple as the hopeful boast of a single convict whom others respected. Before long, however, that spark had grown into a blaze.

Arthur Phillip, first governor of New South Wales, hoped that the craze for “Chinese traveling” was “an evil that would cure itself.” He was wrong.

The first convicts to make a break northward set out on November 1, 1791, little more than four years after the colony was founded. They had arrived there only two months earlier, on the transport ship Queen, which the writer David Levell identifies as the likely carrier of this particular virus. According to the diarist Watkin Tench, a Royal Marines officer who interviewed several of the survivors, they were convinced that “at a considerable distance northward existed a large river which separated this country from the back part of China, and that when it should be crossed they would find themselves among a copper coloured people who would treat them kindly.”

A total of 17 male convicts absconded on this occasion, taking with them a pregnant woman, wife to one; she became separated from the remainder of the group and was soon recaptured. Her companions pressed on, carrying with them their work tools and provisions for a week. According to their information, China lay no more than 150 miles away, and they were confident of reaching it.

The fate of this initial group of travelers was typical of the hundreds who came after them. Three members of the party vanished into the bush, never to be heard from again; one was recaptured after a few days, alone and “having suffered very considerably by fatigue, hunger and heat.” The remaining 13 were finally tracked down after about a week, “naked and nearly worn out by hunger.”

The Blue Mountains formed an impassable barrier to early settlers in New South Wales. Legends soon grew up of a white colony located somewhere in the range, or past it, ruled by a “King of the Mountains.” Not even the first successful passage of the chain, in 1813, killed off this myth.

The failure of the expedition does not seem to have deterred many other desperate souls from attempting the same journey; the “paradise myth,” Robert Hughes suggests in his classic account of transportation, The Fatal Shore, was a psychologically vital counter to the convicts’ “antipodean Purgatory”–and, after all, the first 18 “bolters” had been recaptured before they had the opportunity to reach their goal. Worse than that, the surviving members of the party helped to spread word of the route to China. David Collins, the judge advocate of the young colony, noted that the members of the original group “imparted the same idea to all their countrymen who came after them, engaging them in the same act of folly and madness.”

For the overstretched colonial authorities, it was all but impossible to dissuade other Irish prisoners from following in the footsteps of the earliest bolters. Their threats and warnings lacked conviction; Australia was so little explored that they could never state definitively what hazards absconders would face in the outback; and, given that all the convicts knew there was no fence or wall enclosing them, official attempts to deny the existence of a land route to China seemed all too possibly self-serving. Before long, a stream of “Chinese travelers” began to emulate the trailblazers in groups up to 60 strong–so many that when muster was taken in January 1792, 54 men and 9 women, more than a third of the total population of Irish prisoners, were found to have fled into the bush.

The fragmentary accounts given by the few survivors of these expeditions hint at the evolution of a complex mythology. Several groups were found to be in possession of talismanic “compasses”—which were merely ink drawings on paper—and others had picked up navigational instructions by word of mouth. These latter consisted, Levell says, of “keeping the sun on particular parts of the body according to the time of day.”

Over time, the regular discovery of the skeletons of those who had tried and failed to make it overland to China through the bush did eventually dissuade escaping convicts from heading north. But one implausible belief was succeeded by another. If there was no overland route to China, it was said, there might yet be one to Timor; later, tales began to circulate in the same circles of a “white colony” located somewhere deep in the Australian interior. This legend told of a land of freedom and plenty, ruled over by a benevolent “King of the Mountains,” that would have seemed familiar to medieval peasants, but it was widely believed. As late as 1828, “Bold Jack” Donohue, an Irish bushranger better known as “the Wild Colonial Boy,” was raiding farms in outlying districts in the hope of securing sufficient capital to launch an expedition in search of this arcadia. The colonial authorities, in the person of Phillip’s successor, Governor King, scoffed at the story, but King hardly helped himself in the manner in which he evaded the military regulations that forbade him to order army officers to explore the interior. In 1802 he found a way of deputing Ensign Francis Barrallier to investigate the impenetrable ranges west of Sydney by formally appointing him to a diplomatic post, naming him ambassador to the King of Mountains. Barrallier penetrated more than 100 miles into the Blue Mountains without discovering a way through them, once again leaving open the possibility that the convicts’ tales were true.

The bushranger Bold Jack Donahoe in death, soon after he began raiding farms in the hope of obtaining sufficient supplies to set out in search of the “white colony” believed to exist somewhere in Australia’s interior.

It is impossible to say how many Australian prisoners died in the course of fruitless quests. There must have been hundreds; when the outlaw John Wilson surrendered to the authorities in 1797, one of the pieces of information he bartered for his freedom was the location of the remains of 50 Chinese travelers whose bones—still clad in the tatters of their convict uniforms—he had stumbled across while hiding in the outback. Nor was there any shortage of fresh recruits to the ranks of believers in the tales; King wrote in 1802 that “these wild schemes are generally renewed as often as a ship from Ireland arrives.”

What remained consistent was an almost willful misinterpretation of what the convicts meant by fleeing. Successive governors viewed their absconding as “folly, rashness and absurdity,” and no more than was to be expected of men of such “natural vicious propensities.” Levell, though, like Robert Hughes, sees things differently—and surely more humanely. The myth of an overland route to China was, he writes, “never fully recognised for what it was, a psychological crutch for Irish hope in an utterly hopeless situation.”

Sources

Daniel Field. “A far-off abode of work and pure pleasures.” In Russian Review 39 (1980); Orlando Figes. Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia. London: Penguin, 2003; Robert Hughes. The Fatal Shore: A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787-1868. London: Folio Society, 1998; David Levell. Tour to Hell: Convict Australia’s Great Escape Myths. St Lucia, QLD: University of Queensland Press, 2008; Felix Oinas. “Legends of the Chuds and the Pans.” In The Slavonic and Eastern European Journal 12:2 (1968); Herman Pleij. Dreaming of Cockaigne: Medieval Fantasies of the Perfect Life. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001; R.E.F. Smith (ed). The Russian Peasantry 1920 and 1984. London: Frank Cass, 1977; Richard Stites. Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)