The Portrait of Sensitivity: A Photographer in Storyville, New Orleans’ Forgotten Burlesque Quarter

The Big Easy’s red light district had plenty of tawdriness going on—except when Ernest J. Bellocq was taking photographs of prostitutes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120328093034StoryvilleRaleighRyeGal-web.jpg)

In the decades after Reconstruction, sporting men came to New Orleans from across the country, drawn to horse racing during the day and to the city’s rampant vice by night. In saloons and honky tonks around Vieux Carre (French Quarter), the liquor flowed as men stumbled out onto streets pulsing with Afro-Caribbean styled music played by street urchins and lit by a system of electric flares. Brothels and gaming houses became so prevalent they were said to occupy nearly all of the city, and in the waning years of the 19th century, a reform movement had begun to gain momentum under the stewardship of an alderman named Sidney Story, a respected businessman and sworn enemy of the sin and depravity that he felt was plaguing the Crescent City.

To pen in the brothels and sporting houses so the police might gain some measure of control over the raging lawlessness, Story crafted legislation in 1897 that designated 16 square blocks just off the French Quarter where vice would be legal. Once the law was passed, hundreds of prostitutes celebrated by staging a parade down Canal Street, marching or riding nude or arrayed in elaborate Egyptian costumes. In self-proclaimed victory, they drank liquor and put on a bawdy display that brought hoots from the men on the streets who followed them into New Orleans’ new playground. Sidney Story saw it as a victory, too, but only until he learned that the district’s happy denizens had named it after him.

Storyville was born on January 1, 1898, and its bordellos, saloons and jazz would flourish for 25 years, giving New Orleans its reputation for celebratory living. Storyville has been almost completely demolished, and there is strangely little visual evidence it ever existed—except for Ernest J. Bellocq’s otherwordly photographs of Storyville’s prostitutes. Hidden away for decades, Bellocq’s enigmatic images from what appeared to be his secret life would inspire poets, novelists and filmmakers. But the fame he gained would be posthumous.

E.J. Bellocq was born in New Orleans in August 1873 to an aristocratic white Creole family with, like many the city, roots in France. By all accounts, he was oddly shaped and dwarf-like in appearance; as one New Orleans resident put it, he had very narrow shoulders but “his sitdown place was wide.”

Reminiscent of the French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose misshapen form was believed to be the result of inbreeding, Bellocq was believed to be hydrocephalic. His condition, commonly referred to as “water on the brain,” enlarges the head and often causes convulsions and mental disability. Bellocq’s forehead, one man who knew him said, was very high and “came to a point, and he was somewhat bald.” Bellocq masked it by wearing a hat constantly. He made his living as a commercial photographer, taking pictures of boats in a shipyard, city landmarks and industrial machinery. He was viewed as having no great talent.

Dan Leyrer, another photographer in New Orleans, knew Bellocq from seeing him around a burlesque house on Dauphine Street. He later recalled that people called him “Pap” and that he “had a terrific accent and he spoke in a high-pitched voice, staccato-like, and when he got excited he sounded like an angry squirrel.” Leyrer also noted that Bellocq often talked to himself, and “would go walking around with little mincing steps…he waddled a little bit like a duck.”

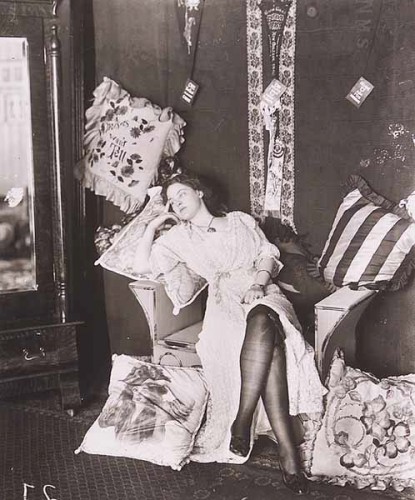

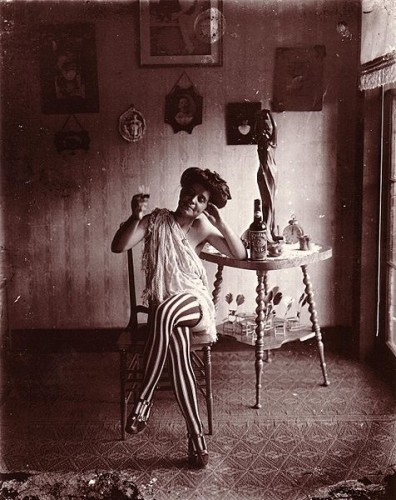

But E. J. Bellocq wasn’t just photographing ships and machines. What he kept mostly to himself was his countless trips to Storyville, where he made portraits of prostitutes at their homes or places of work with his 8-by-10-inch view camera. Some of the women are photographed dressed in Sunday clothes, leaning against walls or lying across an ironing board, playing with a small dog. Others are completely or partially nude, reclining on sofas or lounges, or seated in chairs.

The images are remarkable for their modest settings and informality. Bellocq managed to capture many of Storyville’s sex workers in their own dwellings, simply being themselves in front of his camera—not as sexualized pinups for postcards. If his images of ships and landmark buildings were not noteworthy, the pictures he took in Storyville are instantly recognizable today as Bellocq portraits—time capsules of humanity, even innocence, amid the shabby red-light settings of New Orleans. Somehow, perhaps as one of society’s outcasts himself, Bellocq gained the trust of his subjects, who seem completely at ease before his camera.

Bellocq continued to earn his living as a photographer, but never very successfully. In 1949, at the age of 76, he fell down some stairs in the French Quarter and hit his head; he died a week later in Charity Hospital. His brother Leo, a Jesuit priest, was summoned to the hospital, and when he returned to his brother’s apartment, he discovered the negatives of the portraits. They ended up stored in a junk shop—a run-down bathroom in an old slave quarters.

In 1958, 89 glass negatives were discovered in a chest, and nine years later the American photographer Lee Friedlander acquired the collection, much of which had been damaged because of poor storage. None of Bellocq’s prints were found with the negatives, but Friedlander made his own prints from them, taking great care to capture the character of Bellocq’s work. It is believed that Bellocq may have purposely scratched the negatives of some of the nudes, perhaps to protect the identity of his subjects.

Bellocq was also known to have taken his camera into the opium dens in New Orleans’ Chinatown, but none of those images have been found. His nudes and portraits have influenced the work of countless photographers over the years, and his mysterious life devoted to a secret calling has inspired characters in many novels, as well as a portrayal by Keith Carradine in the Louis Malle film Pretty Baby.

Storyville was shut down at the start of World War I and razed to make way for the Iberville Housing Projects in the early 1940s. A few buildings remain from the storied vice district of New Orleans, but they show nothing of the humanity and the spirit of a Bellocq photograph from that bygone experiment in urban reform.

Sources

Books: Lee Friedlander and John Szarkowski, E.J. Bellocq Storyville Portraits, Little Brown & Co., 1970. Richard Zacks, An Underground Education: Anchor Books, 1999. Al Rose, Storyville, New Orleans, University of Alabama Press, 1978. Richard and Marina Campanella, New Orleans Then and Now, Pelican Publishing, 1999.

Articles: “Sinful Flesh,” by Susan Sontag, The Independent, June 1, 1996. ”Bellocq’s Storyville: New Orleans at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” Weatherspoon Art Museum, http://weatherspoon.uncg.edu/blog/tag/e-j-bellocq/.”E.J. Bellocq,” Photography Now, http://www.photography-now.net/listings/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=438&Itemid=334. ”Hooker Heroes: The Models of Storyville,:” by Blake Linton Wilfong, http://wondersmith.com/heroes/models.htm. 19th Century New Orleans Brothels Revisited in New Book, by Susan Larson, Missourian, April 26, 2009. “The Whores of Storyville,” by David Steinberg, Spectator Magazine. “Storyville: The Red-Light District in New Orleans: Of Red Lights and Blue Books. http://www.southernmusic.net/STORYVILLE.htm http://www.freedomusa.org/coyotela/reviews.html “The Last Days of Ernest J. Bellocq,” by Rex Rose, Exquisite Corpse, http://www.corpse.org/archives/issue_10/gallery/bellocq/index.htm. ”An Interview with David Fulmer,” by Luan Gaines, Curled Up With a Good Book, http://www.curledup.com/intfulm.htm. ”Storyville New Orleans” http://www.storyvilledistrictnola.com/ “E.J. Bellocq 1873-1949) Profotos.com Photography Masters. http://www.profotos.com/education/referencedesk/masters/masters/ejbellocq/ejbellocq.shtml

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)