An Oral History of “Star Trek”

The trail-blazing sci-fi series debuted 50 years ago and has taken countless fans where none had gone before

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/83/8e831889-aaa8-4cda-8509-8ae42407c608/may2016_g01_startrek.jpg)

It was the most wildly successful failure in television history. First shown on NBC 50 years ago this September, the original “Star Trek” lasted just three seasons before it was canceled—only to be resuscitated in syndication and grow into a global entertainment mega-phenomenon. Four live-action TV sequels, with another digital-platform spinoff planned by CBS to launch next year. A dozen movies, beginning with 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture and resuming this July with the director Justin Lin’s Star Trek Beyond. It finds Capt. Kirk (Chris Pine) and Spock (Zachary Quinto) in deep space, where they are attacked by aliens and stranded on a distant planet—a plot that may make some viewers glad that at least the special effects are new. Over the decades “Star Trek” merchandise alone (because who does not need a Dr. McCoy bobblehead?) has reportedly brought in some $5 billion.

This is quite an outpouring for a concept that its creator, the Los Angeles police officer-turned-TV-writer Gene Roddenberry, pitched to producers as a “space western” and once described as a “‘Wagon Train’ to the Stars.” There’s much, much more to the appeal of the original “Star Trek” than gunplay in the wilderness, of course, as countless articles and dissertations have tried to explain, but in one key respect Roddenberry’s notion was right on target: People everywhere, especially Americans, are fascinated by the frontier, whether final or not. And fans are still intrigued that Roddenberry, a World War II veteran, set his 23rd-century multiracial epic in a universe that seemed to be moving beyond bigotry and petty conflict, a cold war-era imagining of the future that was reassuringly counter-dystopian. Plus, you’ve got to love the gadgets—mobile communicators, videoconferencing, diagnostic scanners, talking computers—which have had an uncanny habit of turning up in real life lately, a tribute to the wit and ingenuity of not only Roddenberry but also the show’s designers and writers.

The richness and persistence of the original vision are what make an extensive oral history of “Star Trek” so compelling. (The same cannot be said of “The Newlywed Game,” for instance, another TV show that debuted in 1966.)

For more than 30 years, Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman have made it their mission to document the creative process underlying “Star Trek” in all its iterations. In tens of thousands of hours of interviews conducted everywhere from Gene Roddenberry’s Bel Air mansion to movie set camper trailers, the writers recorded virtually anyone who put his or her stamp on this pop culture monument. The result is The Fifty-Year Mission: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Star Trek: The First 25 Years, excerpted here. (Volume 2 is in the works.) “What I loved about the oral history format,” says Altman, “was that it was like getting 500 people in a room and telling the story in a linear fashion.” It was, adds Gross, a “genuine labor of love.”

Gene Roddenberry (creator and executive producer, “Star Trek”)

I remember myself as an asthmatic child, having great difficulties at 7, 8 and 9 years old, falling totally in love with Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle and dreaming of having his strength to leap into trees and throw mighty lions to the ground.

There was a boy in my class who life had treated badly. He limped, he wheezed. He was a charming, intelligent person. Because of being unable to do many of the things that others were able to do, he had sort of gone into his own world of fantasy and science fiction. He had been collecting the wonderful old Amazing and Astounding magazines, and he introduced me to science fiction. I then discovered in our neighborhood, living above a garage, an ex-con who had come into science fiction when he was in prison. He introduced me to John Carter and those wonderful Burroughs things. By the time I was 12 or 13 I had been very much into the whole science fiction field.

In World War II, Roddenberry served in the U. S. Army Air Corps as a B-17 pilot. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department in 1949, and wrote speeches for Chief William Parker as well as articles for the LAPD newsletter, The Beat. Resigning in 1956, Roddenberry provided scripts to the screenwriter Sam Rolfe, for “Have Gun Will Travel,” the TV western starring Richard Boone. Roddenberry had his first pilot produced by MGM in 1963, for the short-lived NBC series “The Lieutenant.” The studio turned down his pitch for a new series called “Star Trek.” But his agents contacted Desilu Studios, which was looking to produce more dramas after years of success in comedy.

Gene Roddenberry

I was tired of writing for shows where there was always a shoot-out in the last act and somebody was killed. “Star Trek” was formulated to change that. I had been a freelance writer for about a dozen years and was chafing at the commercial censorship on television. You really couldn’t talk about anything you cared to talk about. It seemed to me that perhaps if I wanted to talk about sex, religion, politics, make some comments against Vietnam, and so on, that if I had similar situations involving these subjects happening on other planets to little green people, indeed it might get by, and it did.

Dorothy “D.C.” Fontana (writer, “Star Trek” story editor)

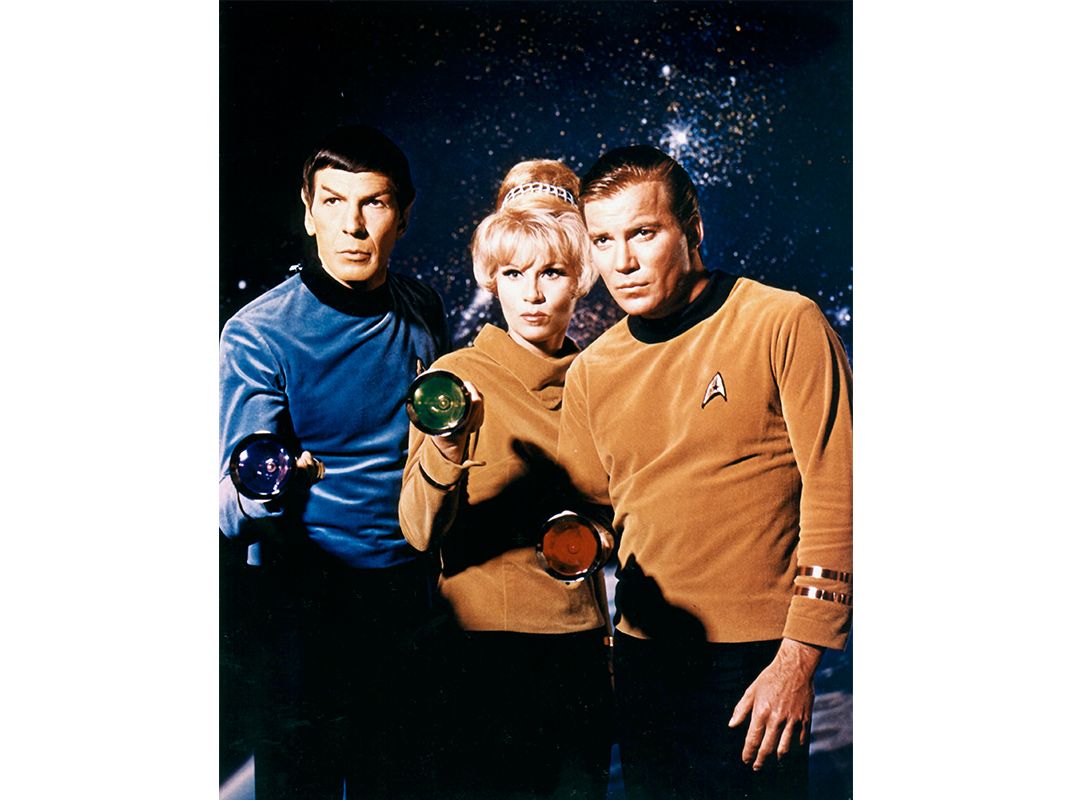

Gene asked me to read the very first proposal for “Star Trek” in 1964. I said, “I have only one question: Who’s going to play Mr. Spock?” He pushed a picture of Leonard Nimoy across the table.

Gene Roddenberry

Leonard Nimoy was the one actor I definitely had in mind—we had worked together previously. I was struck at the time with his high Slavic cheekbones and interesting face, and I said to myself, “If I ever do this science fiction thing, he would make a great alien. And with those cheekbones some sort of pointed ear might go well.” To cast Mr. Spock I made a phone call to Leonard and he came in. That was it.

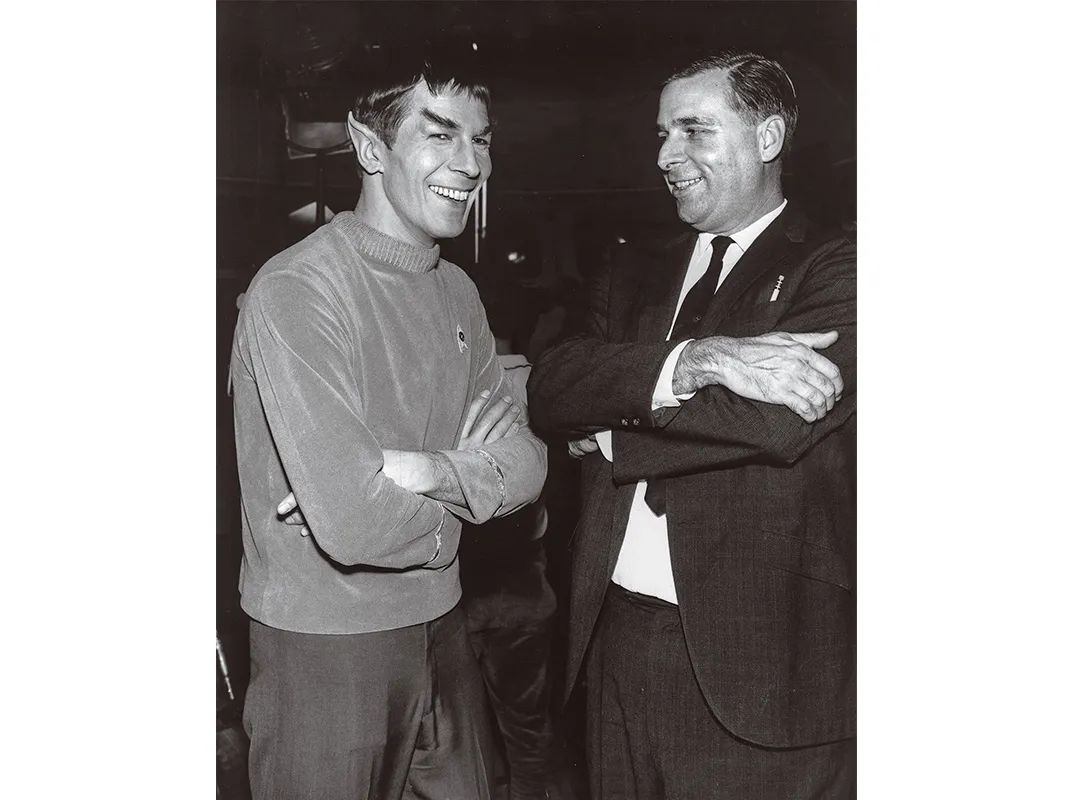

Leonard Nimoy (actor, “Mr. Spock”)

I went in to see Gene at Desilu Studios and he told me that he was preparing a pilot for a science fiction series to be called “Star Trek,” that he had in mind for me to play an alien character. I figured all I had to do was keep my mouth shut and I might end up with a good job here. Gene told me that he was determined to have at least one extraterrestrial prominent on his starship. He’d like to have more, but making human actors into other life-forms was too expensive for television in those days. Pointed ears, skin color, plus some changes in eyebrows and hair style were all he felt he could afford, but he was certain that his Mr. Spock idea, properly handled and properly acted, could establish that we were in the 23rd century and that interplanetary travel was an established fact.

Marc Cushman (author, “These Are the Voyages”)

Desilu came into existence because Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz owned “I Love Lucy.” It was the first time someone owned the rerun rights to a show. Seems like a no-brainer today, but back then no one had done it. Eventually CBS bought the rerun rights back from Lucy and Desi for a million dollars, a lot of money back then. Lucy and Desi take that money and buy RKO and turn it into Desilu Studios. The company grows, but then the marriage falls apart and Lucy ends up running the studio and by this point, they don’t have many shows. Lucy says, “We need to get more shows on the air,” and “Star Trek” was the one she took on, because she thought it was different.

Herbert F. Solow (executive in charge of production, “Star Trek”)

I had so many people at the studio, so many old-timers trying to talk me out of it. “You’re going to bankrupt us, you can’t do this. NBC doesn’t want us anyway, who cares about guys flying around in outer space?” The optical guy said it was impossible to do.

Marc Cushman

Desi wasn’t there anymore. So Lucy is asking herself, “What would Desi do?” because she really loved and respected him. “Desi would get more shows on the air that we own, not just that we’re producing for other companies.” That was her reasoning to do “Star Trek”—and she felt that this show could, if it caught on, rerun for years like “I Love Lucy.” And guess what? Those two shows—“I Love Lucy” and “Star Trek”—are two shows that have been rerunning ever since they originally aired.

In the teleplay for the first pilot, “The Cage,” starring Jeffrey Hunter as Capt. Christopher Pike, Roddenberry described the establishing shot in detail: “Obviously not a primitive ‘rocket ship’ but rather a true space vessel, suggesting unique arrangements and exciting capabilities. As CAMERA ZOOMS IN we first see tiny lettering ‘NCC 1701- U.S.S. ENTERPRISE.’”

Walter M. “Matt” Jefferies (production designer, “Star Trek”)

I had collected a huge amount of design material from NASA and the defense industry which was used as an example of designs to avoid. We pinned all that material up on the wall and said, “That we will not do.” And also everything we could find on “Buck Rogers” and “Flash Gordon” and said, “That we will not do.” Through a process of elimination, we came to the final design of the Enterprise.

Gene Roddenberry

I’d been an Army bomber pilot and fascinated by the Navy and particularly the story of the Enterprise, which at Midway really turned the tide in the whole war in our favor. I’d always been proud of that ship and wanted to use the name.

Roddenberry’s attention to detail even extended to the ship’s computer at a time when computers were punch card–operated behemoths that filled entire rooms. In a memo on July 24, 1964, to production designer Pato Guzman, Roddenberry suggested, “More and more I see the need for some sort of interesting electronic computing machine designed into the USS Enterprise, perhaps on the bridge itself. It will be an information device out of which the crew can quickly extract information on the registry of other space vessels, spaceflight plans for other ships, information on individuals and planets and civilizations.”

Gene Roddenberry

The ship’s transporters—which let the crew “beam” from place to place—really came out of a production need. I realized with this huge spaceship, I would blow the whole budget of the show just in landing the thing on a planet. And secondly, it would take a long time to get into our stories, so the transporter idea was conceived so we could get our people down to the planet fast and easy, and get our story going by Page 2.

Howard A. Anderson (visual effects artist, “Star Trek”)

For the transporter effect, we added another element: a glitter effect in the dematerialization and rematerialization. We used aluminum dust falling through a beam of high-intensity light.

Though the network had warned the studio not to make the pilot too esoteric—“Be certain there are enough explanations on the planet, the people, their ways and abilities so that even someone who is not a science fiction aficionado can clearly understand and follow the story,” a 1964 memo said—the network wasn’t satisfied. NBC commissioned another pilot—a rare second chance at being picked up for a series.

Gene Roddenberry

The reason they turned the pilot down was that it was too cerebral and there wasn’t enough action and adventure. “The Cage” didn’t end with a chase and a right cross to the jaw, the way all manly films were supposed to end. There were no female leads then—women in those days were just set dressing. So, another thing they felt was wrong was that we had Majel as a female second-in-command of the vessel.

Majel Barrett (actress, "Number One,""Nurse Christine Chapel")

NBC felt that my position as Number One would have to be cut because no one would believe that a woman could hold the position of second-in-command.

Gene Roddenberry

Number One was originally the one with the cold, calculating, computerlike mind. When we had to eliminate a feminine Number One—I was told you could cast a woman in a secretary’s role or that of a housewife, but not in a position of command over men on even a 23rd-century spaceship—I combined the two roles into one. Spock became the second-in-command, still the science officer but also the computerlike, logical mind never displaying emotion.

Leonard Nimoy

Vulcan unemotionalism and logic came into being.Gene felt the format badly needed the alien Spock, even if the price was acceptance of 1960s-style sexual inequality.

The network’s objections to Roddenberry’s Spock included taking exception to the character’s pointed ears, perceived as imparting a vaguely sinister Satanic appearance.

Gene Roddenberry

The idea of dropping Spock became a major issue. I felt that was the one fight I had to win, so I wouldn’t do the show unless we left him in. They said, “Fine, leave him in, but keep him in the background, will you?” And then when they put out the sales brochure when we eventually went to series, they carefully rounded Spock’s ears and made him look human so he wouldn’t scare off potential advertisers.

Work on the second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” began in 1965. The show aired on September 22, 1966, and featured William Shatner as Capt. James T. Kirk, replacing actor Jeffrey Hunter.

Gene Roddenberry

At that time, TV was full of antiheroes, and I had a feeling that the public likes heroes. People with goals in mind, with honesty and dedication, so I decided to go with the straight heroic roles, and it paid off. My model for Kirk was Horatio Hornblower from the C.S. Forester sea stories. Shatner was open-minded about science fiction, and a marvelous choice.

William Shatner (actor, “James T. Kirk”)

I talked to Gene Roddenberry about the objectives we hoped to achieve, and one was serious drama as well as science fiction. I felt confident that “Star Trek” would keep those serious objectives for the most part, and it did.

Scott Mantz (film critic, “Access Hollywood”)

I’d follow Kirk in a second. Shatner’s performance as Kirk is the reason I became a “Trek” fan.

Leonard Nimoy

Bill Shatner’s broader acting style created a new chemistry between the captain and Spock.

William Shatner

Captain Kirk and I melded. It may have been only out of the technical necessity; the thrust of doing a television show every week is such that you can’t hide behind too many disguises. You’re so tired that you can’t stop to try other interpretations of a line, you can only hope that this take is good, because you’ve got five more pages to shoot. You have to rely on the hope that what you’re doing as yourself will be acceptable. Captain Kirk is me. I don’t know about the other way around.

James Doohan (actor, “Montgomery ‘Scotty’ Scott”)

[A few days] before they were actually going to shoot the second “Star Trek” pilot, the director, Jim Goldstone, called me and said, “Jimmy, would you come in and do some of your accents for these ‘Star Trek’ people?” I had no idea who they were, but I did that on a Saturday morning. They handed me a piece of paper—there was no part there for an engineer, it was just some lines, but every three lines or so I changed my accent and ended up doing eight or nine accents for that reading. At the end, Gene Roddenberry said, “Which one do you like?” I said, “To me, if you want an engineer, he’d better be a Scotsman,” because those were the only engineers I had read anything about—all the ships they had built and so forth. Gene said, “Well, we rather like that, too.”

George Takei (actor, “Hikaru Sulu”)

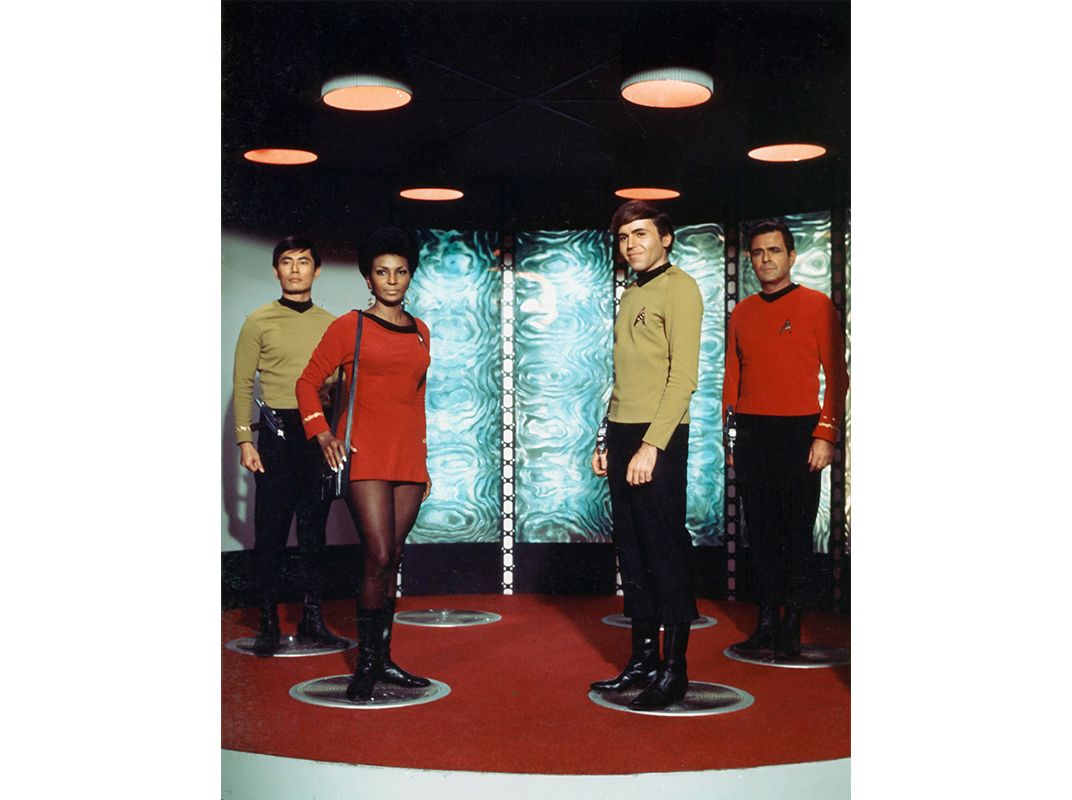

The first time I talked to Gene about “Star Trek,” it was for the second pilot and it was an exhilarating prospect, because almost every other opportunity was either inconsequential or defamatory, and here was something that was a breakthrough for a Japanese-American actor. Until then any regular series roles for an Asian or an Asian-American character were either servants, buffoons or villains.

Alexander Courage (composer, “Star Trek”)

When Lucille Ball bought Desilu, Wilbur Hatch came in as head of music. When “Star Trek” came on the scene, Wilbur suggested me to Roddenberry and I turned out a theme. Roddenberry liked it and that was it. He said, “I don’t want any space music. I want adventure music.”

The second pilot became a monumental achievement: It persuaded NBC to greenlight the series.

Gene Roddenberry

The biggest factor in selling the second pilot was that it ended up in a hell of a fistfight with the villain suffering a painful death. Then, once we got “Star Trek” on the air, we began infiltrating a few of our ideas, the ideas the fans have all celebrated.

Robert H. Justman (associate producer, “Star Trek”)

On the last day of production when we were a day over, we did two days’ work in one day. That’s the day that Lucy came on the stage, because we were supposed to have an end-of-picture party and we were still shooting, so in between setups she helped Herb Solow and me sweep out the stage. I think she just did that for effect, because she wanted to get the party started.

On March 6, 1966, Roddenberry dispatched a Western Union telegram to Shatner at the Hotel Richmond in Madrid: “Dear Bill. Good news. Official pickup today. Our Five Year Mission. Best Regards, Gene Roddenberry.”

Not long after “Star Trek” was launched, the audience embraced Leonard Nimoy’s Spock, and the stoic Vulcan science officer soon threatened to eclipse Captain Kirk. Nimoy came up with a list of demands that resulted in the possibility that the character would be replaced. In the end, Nimoy’s demands were met, and the scripts began focusing on Kirk and Spock as a team. But the sense of competition continued.

Marc Cushman

They almost didn’t have Spock for the second season of “Star Trek.” The fan mail got so intense during the first year, sacks and sacks of mail every day. His agent said, “He’s getting only $1,250 a week and he needs a raise.” But Desilu is losing money on the show and the board of directors was thinking of canceling it, even if NBC wanted to continue, because it was bankrupting the studio. The one that broke the stalemate was the one that didn’t want Spock in the first place: NBC. “You are not doing the show without that guy. Pay him whatever you need to pay him.”

David Gerrold (writer, “The Trouble With Tribbles”)

The problems with Shatner and Nimoy really began during the first season when Saturday Review did this article about “Trek” which stated that Spock was much more interesting than Kirk, and that Spock should be captain. Well, nobody was near Shatner for days. He was furious. All of a sudden, the writers are writing all this great stuff for Spock, and Spock, who’s supposed to be a subordinate character, suddenly starts becoming the equal of Kirk.

Ande Richardson (assistant to writer Gene L. Coon)

Shatner would take every line that wasn’t nailed down. “This should be the captain’s line!” He was very insecure.

Herbert F. Solow

The last thing we wanted was to have the network, the sponsors or the television audience feel that it was not a wonderful, marvelous family on “Star Trek.” We didn’t want anybody to see a crack in this dam that we built.

If push came to shove, and we had to recast both characters, it would have been easier to recast Bill’s part than Leonard’s, so you tell me: Who’s the star of the show?

William Shatner

Occasionally, I’ll hear something from an ardent fan of mine who’ll say, “So and so said this about you.” And it bewilders me because I have had no trouble with them. We have done our job and gone on and I have never had bad words with anyone.

On August 17, 1967, Roddenberry addressed an ultimatum to Shatner and Nimoy, with DeForest Kelley (Dr. McCoy) thrown in for good measure:

“Toss these pages in the air if you like, stomp off and be angry, it doesn’t mean that much since you’ve driven me to the edge of not giving a damn,” Roddenberry wrote in that letter, excerpted here for the first time: “No, William, I’m not really writing this to Leonard and just including you as a matter of psychology. I’m talking to you directly and with an angry honesty you haven’t heard before. And Leonard, you’d be very wrong if you think I’m really teeing off at Shatner and only pretending to include you. The same letter to both; you’ve pretty well divided up the market on selfishness and egocentricity.

“Star Trek began as one of the TV productions in town where actors, as fellow professionals, were not only listened to but actually invited to bring their script and series comments to the production office. When small problems and pettiness begins to happen as it happens on all shows, I instructed our people that it should be overlooked where possible because we should all understand the enormous physical and emotional task of your job....The result of Gene Roddenberry’s policy of happy partnership? Star Trek is going down the drain.

“. . . I want you to realize fully where your fight for absolute screen dominance is taking you. It’s already affecting the image of Captain Kirk on the screen. We’re heading for an arrogant, loud, half-assed Queeg character who is so blatantly insecure upon that screen that he can’t afford to let anyone else have an idea, give an order, or solve a problem. You can’t hide things like that from an audience.

“And now, Leonard. I must say that if I were Shatner, I’d be nervous and edgy about you by now, too. For a man who makes no secret of his own sensitivity, you show a strange lack of understanding of it in your fellow actors.

“For as long as I stay with the show, starting Monday,” Roddenberry decreed, “there will be no more line switches from one to another. No more of the long discussions about scenes which lose us approximately a half day of production a show—the director will permit it only when there is a valid dramatic story or interpretation point at stake which he believes makes it necessary. The director will be told he is also replaceable and failure to stay on top and in charge of the set will be grounds for his dismissal.

“All right, my three former friends and ‘unique professionals,’ that’s it. In straight talk.”

David Gerrold

All the episodes hold together because Shatner holds it together. Spock is only good when he has someone to play off of. Spock working with Kirk has the magic and it plays very well, and people give all of the credit to Nimoy, not to Shatner.

Leonard Nimoy

During the series we had a failure—I experienced it as a failure—in an episode called “The Galileo Seven.” The Spock character had been so successful that somebody said, “Let’s do a show where Spock takes command of a vessel.” We had this shuttlecraft mission where Spock was in charge. I really appreciated the loss of the Kirk character for me to play against. The Bill Shatner Kirk performance was the energetic, driving performance, and Spock could kind of slipstream along and offer advice, give another point of view. Put into the position of being the driving force, the central character, was very tough for me.

Thomas Doherty (professor of American studies, Brandeis University)

At the core of “Star Trek” is something profound, which is teamwork and adventure and tolerance. That’s why it’s a World War II motif in the space age. It really is a team; you’re making a heroic contribution by doing your bit.

At the beginning of the second season, several changes greeted viewers. Not only was DeForest Kelley’s name now added to the opening credits, there was a new face at the helm: Navigator Pavel Andreievich Chekov, played by Walter Koenig.

Gene Roddenberry

The Russians were responsible for the Chekov character. They put in Pravda that, “Ah, the ugly Americans are at it again. They do a space show, and they forget to include the people who were in space first.” And I said, “My God, they’re right.”

Walter Koenig (actor, “Pavel Chekov”)

They were looking for someone who would appeal to the bubblegum set. All that stuff about Pravda, that’s all nonsense. That was all just publicity. They wanted somebody who would appeal to 8- to 14-year-olds and the decision was to make him Russian. My fan mail came from 8- to 14-year-olds who weren’t that aware of the cold war. Getting fan mail was so novel to me that I read every single letter I got. I was getting about 700 letters a week.

Robert H. Justman

We had another problem in the second season. We were cut down on how much we could spend per show by a sizable amount of money.

Marc Cushman

Lucille Ball lost her studio because of “Star Trek.” She had gambled on the show, and you can read the memos where her board of directors is saying, “Don’t do this show, it’s going to kill us.” But she believed in it. She moved forward with it, and during the second season she had to sell Desilu to Paramount Pictures. Lucille Ball gave up the studio that she and her husband built, it’s all she had left of her marriage, and she sacrificed that for “Star Trek.”

Ralph Senensky (director, “Metamorphosis”)

Desilu was like a family. Herb Solow [the production head] used to come down and talk with you on the soundstage. Herb went out of his way to help you. Can you imagine a studio working like that? When Paramount bought it, a kind of corporate mentality took over. That’s why I resent Paramount having such a hit in “Star Trek.” If they had their way, they would have killed it off. It survived in spite of them. Now they have this bonanza making them all of this money.

Marc Cushman

Lucy’s instincts were right about “Star Trek,” that it would become one of the biggest shows in syndication ever. The problem was that her pockets weren’t deep enough. They were losing $15,000 an episode, which would be like $500,000 per episode today. You know, if she could have hung on just six months longer, it would have worked out, because by the end of the second season, once they had enough episodes, “Star Trek” was playing in, I believe, 60 different countries around the world. And all of that money is flowing in.

She had no choice but to sell. She actually took off and went to Miami. She ran away because it was so heartbreaking to sign the contract. They had to track her down to get her to do it. There’s a picture of her cutting the ribbon after they’ve torn down the wall between Paramount and Desilu, and she’s standing next to the CEO of Gulf and Western, which owns both studios now, and she’s trying to fake this smile for the camera, and you know it’s just killing her.

Among the now-classic episodes in Season 2 of the original are “Amok Time,” in which Spock is driven to return to Vulcan to mate or die and finds himself in a battle to the death with Kirk.

Joseph Pevney (director, “Amok Time”)

What made the fight in “Amok Time” dramatically interesting is that it took place between Kirk and Spock. During this episode, Leonard Nimoy and I also worked out the Vulcan salute and the statement “live long and prosper” together.

Gene Roddenberry

Leonard Nimoycame into my office and said, “I feel the need for a Vulcan salutation, Gene,” and he showed it to me. Then he told me a story about when he was a kid in synagogue. The rabbis said, “Don’t look or you’ll be struck dead or blind,” but Leonard looked and, of course, the rabbis were making that Vulcan sign. The idea of my Southern kinfolk walking around giving each other a Jewish blessing so pleased me that I said, “Go!”

Joseph Pevney

“The Trouble With Tribbles” was a delightful show. I had a lot of fun with it, went out and shopped for the tribbles. My biggest contribution was getting the show produced, because there was a feeling that we had no business doing an outright comedy. Bill Shatner had the opportunity to do the little comic bits he loves.

Season 2 also featured visits to a number of Earthlike planets, including one where the society mirrored the Roman Empire.

Ralph Senensky

Gene Roddenberry is a very creative man. When we did “Bread and Circuses,” we were doing the Roman arena in modern times with television. We didn’t want to tip that we were doing a Christ story from the word go. Originally when they were talking about the sun, you knew right away that they were talking about the son of God.

Dorothy “D.C.” Fontana

Certainly there was a nice philosophy going on there with the worshiping of the “sun,” and then the indication that it was the son of God, that Jesus or the concept had appeared on other planets.

The series was not a ratings powerhouse. Indeed, it seemed that Season 2 could very well be the show’s last. The future was in the hands of the fans.

Bjo & John Trimble (longtime fans)

Cancellation was certain at the end of the second season. We wrote up a preliminary letter, ran it off on our ancient little mimeograph machine, and mailed it out to about 150 science fiction fans. We didn’t have enough money to have a letter printed, so we used the Rule of Ten: Ask ten people to write a letter and they ask ten people to write a letter, and each of those ten asks ten people to write a letter.

NBC was convinced that “Star Trek” was watched only by drooling idiot 12-year-olds. They managed to ignore the fact that people such as Isaac Asimov and a multitude of other intellectuals enjoyed the show. So, of course, the suits were always looking for reasons to cancel shows they didn’t trust to be a raging success.

Elyse Rosenstein (early organizer of “Star Trek” conventions)

Do you realize how many pieces of mail NBC eventually received on “Star Trek”? They usually got about 50,000 for the year on everything, but the “Star Trek” campaign generated one million letters. They were handling the mail with shovels—they didn’t know what to do with it. So they made an unprecedented on-air announcement that they were not canceling the show and that it would be back in the fall.

Gene Roddenberry

The letter-writing campaign surprised me. What particularly gratified me was not the fact that there was a large number of people who did that, but I got to meet and know “Star Trek” fans, and they range from children to presidents of universities.

John Meredyth Lucas (producer; writer, “Patterns of Force”)

Some of the most fanatic support came from Caltech.

Gene Roddenberry

We won the fight when the show got picked up for a third season. NBC was certain I was behind every fan, paying them off. And they finally called me up and said, “Listen, we know you’re behind it.” And I said, “That’s very flattering, because if I could start demonstrations around the country from this desk, I’d get the hell out of science fiction and into politics.”

“Star Trek” concluded its second season on a high note, with NBC essentially acknowledging the success of the fans’ letter-writing campaign by announcing that the series would be returning.

Gene Roddenberry

I told NBC that if they would put us on the air as they were promising—on a weeknight at a decent time slot, 7:30 or 8 o’clock—I would commit myself to produce “Star Trek” for the third year. Personally produce the show as I had done at the beginning. About ten days or two weeks later, I received a phone call at breakfast, and the network executive said, “Hello, Gene, baby . . .” I knew I was in trouble right then. He said, “We have had a group of statistical experts researching your audience, and we don’t want you on a weeknight at an early time. We have picked the best youth spot that there is. All our research confirms this and it’s great for the kids and that time is 10 o’clock on Friday nights.” I said, “No doubt this is why you had the great kiddie show ‘The Bell Telephone Hour’ on there last year.” As a result, the only gun I then had was to stand by my original commitment, that I would not personally produce the show unless they returned us to the weeknight time they promised.

David Gerrold

Roddenberry, rather than try and do the very best show possible, walked away and picked Fred Freiberger [as the producer]. I wish Roddenberry had been there in the third season to take care of his baby.

Marc Cushman

NBC didn’t like Gene Roddenberry, and they didn’t like the type of shows that “Star Trek” was airing. It was too controversial and too sexy, and they couldn’t get Roddenberry to tone it down. So they move it to Friday night—they didn’t even want to pick it up, but there was the letter-writing campaign that made them cry uncle. They put it in the death slot. And they knew when they picked it up that they were determined that Season 3 would be the last year.

Robert H. Justman

If your audience is high-school kids and college-age people and young married people, they’re not home Friday nights. They’re out, and the old folks weren’t watching. So our audience was gone.

Margaret Armen (writer, “The Paradise Syndrome”)

Working with Gene was marvelous, because he was “Star Trek” and he related to the writers. Fred came in and to him “Star Trek” was “tits in space.” And that’s a direct quote. Fred had been signed to produce and was being briefed. He watched an episode with me, smoking a big cigar, and said, “Oh, I get it. Tits in space.” You can imagine how a real “Star Trek” buff like myself reacted to that.

Fred Freiberger (producer, “Star Trek,” Season 3)

Our problem was to broaden the viewer base. To do a science fiction show, but get enough additional viewers to keep the series on the air. I tried to do stories that had a more conventional story line within the science fiction frame.

Marc Cushman

You had some of the most talented people from “Star Trek” that were leaving. You didn’t have Gene Coon, Gene Roddenberry or Dorothy Fontana finessing the scripts. It’s like having the Beatles and taking away John Lennon and Paul McCartney. “OK, we still have George and Ringo. We’re still the Beatles.” No, you’re not. You’re still good, but not as good.

James Doohan

Fred Freiberger had no inventiveness in him at all. Paramount bought Desilu and here was this damn space show as part of the package and they couldn’t care less about it.

William Shatner

There was a feeling that a number of Fred Freiberger’s shows weren’t as good as the first and second season, and maybe that’s true. But he did have some wonderfully brilliant shows and his contribution has never been acknowledged.

Bjo & John Trimble

The third season ground down, show after show being worse than the last, until even the authors of the scripts were having their names removed or using pseudonyms. To be fair, there were a few good scripts in the third season, but in the main those few seemed to be almost mistakes that slipped by.

While the third year of “Star Trek” has largely been dismissed as a creative failure, several notable episodes were produced. “Spectre of the Gun” is a surrealistic western in which Kirk, Spock and McCoy find themselves reliving the shootout at the O.K. Corral. “Day of the Dove” focuses on an energy force that feeds on hatred. In “Plato’s Stepchildren,” aliens with telekinetic abilities torture Enterprise crewmen for their amusement—and Kirk and Uhura share television’s first interracial kiss.

Bjo & John Trimble

The last third-season episode, “Turnabout Intruder,” was very good; it might have won an Emmy for William Shatner. But all TV shows got rescheduled for President Eisenhower’s funeral coverage. So the episode missed the Emmy-nomination deadline.

Scott Mantz

That’s how production ended. There is something somewhat apropos about the last words of the last episode, “Turnabout Intruder”: “Her life could have been as rich as any woman’s. If only...If only.” And then Kirk walks off.