The road out of Mount Hagen deteriorates by the mile, the pitted blacktop of the little city crumbling to dirt before collapsing into reddish ruts scraped through the deep green of Papua New Guinea’s highlands. In the final stretch before Kilima, a bedraggled coffee plantation in the Nebilyer Valley, our Toyota Land Cruiser has to crawl in low gear, wobbling and tottering through craters and washouts.

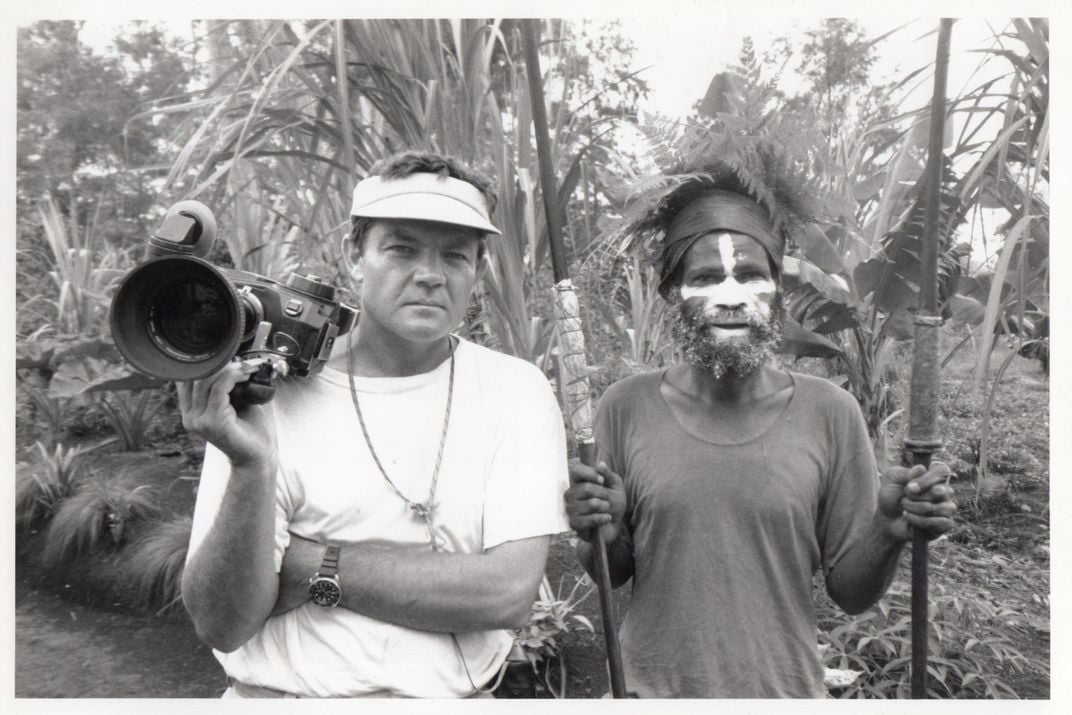

Bob Connolly bounces in the front seat, rolling with the pitch and yaw. He’s just over 70 years old but sturdy, dark-haired and barrel-chested, with a round face that still seems boyish. He grumbles about the drive: too much traffic in town, too little maintenance everywhere else. When he was a younger man, the drive from Mount Hagen to Kilima took him 35 minutes. Now it takes twice as long.

The highlands seemed to hold so much promise when Bob first came to Kilima in the early 1980s. Bob is an Australian documentary filmmaker, and he lived here for years in a hut thatched with kunai grass, making films with his wife, Robin Anderson. The plantation sprawled in endless rows, trees heavy with coffee cherries, wide fields pale with virgin beans drying in the sun. Back then, Kilima’s owner, Joe Leahy, was wealthy and powerful, and he employed dozens of local people to tend his groves and work his pulping factory. Many in the Ganiga tribe eventually became his partners, and they were going to get rich in the coffee business, too.

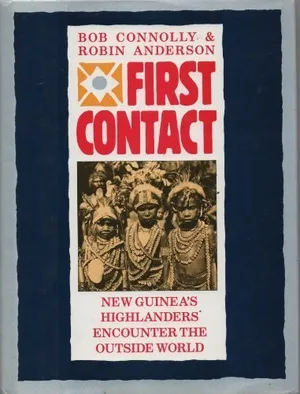

Bob and Robin made three documentaries in the highlands, two of them about Joe Leahy and his neighbors. Each was a triumph, and they still are recognized as such, icons of a genre, touchstones of both anthropology and film. The initial one, First Contact, was nominated for an Academy Award, and the last, Black Harvest, had “extraordinary historical resonance,” the New York Times wrote, “so rich that watching it feels like taking an inspired crash course in economics and cultural anthropology.” Newsweek said it had “the scale and richness of classical tragedy.” Which was true, because everything ended so badly.

On a clear, bright summer morning more than two decades later, Bob inhales a great gulp of crystalline air. Away from Mount Hagen, a chaotic burgh wrapped in barbed wire and wood smoke, the highlands are pristine. Bob always was struck by that, the clarity of the place. As for the rest—Kilima, Joe, the Ganiga who have lived on this land for untold generations—Bob isn’t sure how it all turned out, and that’s why he’s back for the first time in more than 25 years. Maybe he’ll even find enough story for a fourth film.

The road tumbles down a final derelict hill and flattens into a dirt plain between a rusted-out shed, which is old, and an iron-roofed fundamentalist church, which is new. Then it narrows and rises again toward Joe’s house, up on the next hill. There are five people walking along the road between the shed and the church, one of them a Ganiga man in a blue jacket and cap that seem too warm for the morning. He’s waving for the Toyota to stop.

It takes Bob a moment to recognize the man in the cap, to sort the face and the name from his memory. “Paraka!” he then says brightly, and Paraka beams. He leans in through the window, holds Bob in a light embrace. “Happy to see you,” Bob tells him in his still serviceable pidgin. “What’s going on up at the house?” Bob asks. Bob’s heard that Joe is going to kill a pig in honor of his return. He thinks there might be a celebration, a dozen or more tribesmen, all old friends. Perhaps there will be speeches, maybe even a welcoming sing-sing. “No, don’t tell me,” Bob says suddenly. He wants to be surprised.

Paraka watches as the Toyota starts up the hill, but he does not follow. He knows he’s not welcome at Joe Leahy’s place. Joe has a complicated relationship with his Ganiga neighbors, and that hasn’t changed at all.

**********

Long after missionaries and Europeans settled on the coast of New Guinea in the 19th century, the mountainous interior remained unexplored. As recently as the 1920s, outsiders believed the mountains, which run the length of the island from east to west, were too steep and rugged for anyone to live there. But when gold was discovered 40 miles inland, prospectors went north across the Coral Sea to seek their fortunes. Among them were three brothers from Queensland, Australia: Michael, James and Daniel Leahy, the children of Irish immigrants, who in the early 1930s hiked to the top of the ridges with a group of native porters and gun bois (or armed guards) from the coast.

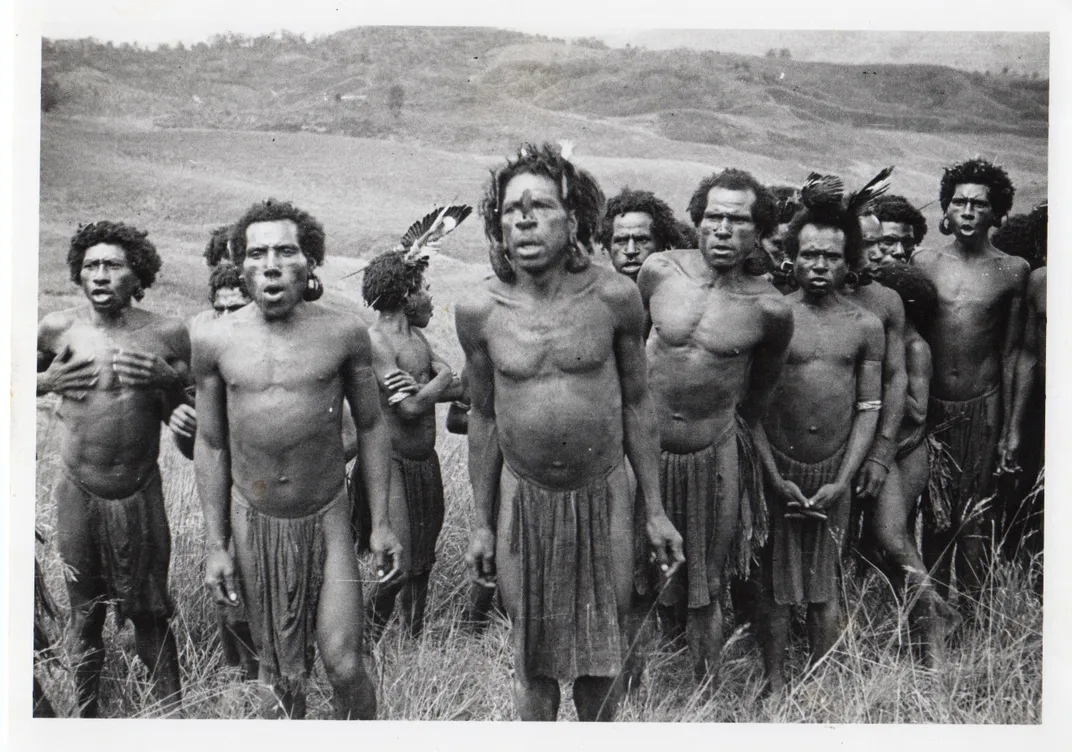

In the highlands the Leahys found wide, fertile valleys, groomed with garden plots that were later estimated to feed a million inhabitants sorted into hundreds of tribes and clans. The highlanders lived in huts of timber and kunai grass, used stone tools and fought with wooden spears and arrows. Just as white settlers had been unaware of their existence, the highlanders had no idea that anyone lived beyond the mountains.

At first, they suspected the white men were spirits, or maybe lightning come to earth. More curious than afraid, they traded with the white men, sweet potatoes and pigs and women in exchange for steel axes and shells (plentiful on the coast, but rare and highly prized in the highlands). When the expedition encountered new tribes, Michael “Mick” Leahy, the oldest brother and acknowledged leader, would shoot a pig to demonstrate his superior firepower. If a tribal “big man” tried to rally his warriors into a raiding party, Mick and his gun bois would shoot a few of them, too.

The Leahys traipsed through the highlands until, in 1933, they struck a claim near what is now Mount Hagen. There they built an airstrip, with friendly locals stamping the dirt flat in endless sing-sings, and settled in to make a modest fortune dredging shiny rocks from the streams. In time, the Leahys became famous for “opening” the interior to the outside world, and Mount Hagen grew into one of the country’s largest cities.

Nearly 50 years later, Bob Connolly, then a young journalist in Sydney, met Robin Anderson at the Australian Broadcasting Company, where they both worked making documentaries for television. The two fell in love and began looking for independent projects. One evening, at dinner with a friend who happened to be working on an oral history of the colonization of New Guinea, they learned that Mick Leahy, besides being a prospector and explorer, was also an amateur photographer—and not only had he brought a still camera and a movie camera on his expeditions, but his films and photographs were rumored to have survived.

Robin tracked down one of Mick Leahy’s sons in the coastal Papua New Guinea town of Lae, who went into his attic and retrieved 11 canisters of film. What was more, Robin heard stories that there were people in the highlands who still remembered when the white men first came. After flying back to Sydney, she soon returned—this time with Bob, along with camera equipment, and the two spent months retracing the Leahys’ original route.

The resulting film, First Contact, was released in 1983. It was a remarkable achievement, combining Mick’s jerky black-and-white footage and photographs of his encounters with the highlanders with Bob and Robin’s interviews with native men and women who had been there. Intercut with those were lengthy sit-downs with the two surviving Leahy brothers, both by then very old men and long settled in the highlands. (Mick had died in 1978.) Bob and Robin produced the film in the format to which they were accustomed: 54 minutes, television length, shot by a hired crew, narrated by a professional voice actor. A reconstruction of an archetypal story like this one—among the last encounters between two different cultures who had no knowledge of the other—must usually be dredged from diaries and ships’ logs and other centuries-old accounts and recreated from fragments, from dust. In this case, though, there was no need to guess at how the highlanders and the white men saw each other, to puzzle it out from stray clues: they all looked into a camera and spoke for themselves. “We not only have Cortez on the Aztecs,” Bob told friends. “We have the Aztecs on Cortez!”

They had a tight shot of an old man in a knit cap and a polyester shirt, recalling what it was like as a boy when the white men came. “This is what the people said: They are not of the living. They must be our ancestors from the place of the dead. We knew nothing then of the outside world. We thought we were the only living people. We believed our dead went over there”—he pointed to somewhere distant—“turned white and came back as spirits.”

They had Danny Leahy, mostly deaf and half-blind, explaining the pragmatism of violence with a touch of defensiveness: “The only reason that we killed people was simply that if we hadn’t have killed them, they would have killed us and all our carriers, all the people that were with us. The gold had nothing to do with it.”

Another old highlander, squatting on a slope: “My father had his head blown to pieces. And then they shot people there,” he said, gesturing. “And over there. Back there, and all around.”

Nine minutes from the end, the man in the wool cap again, now wearing a threadbare coat and tie: “In the past, every man was his own boss. But this ended when the white man came. When they told us to work, we worked.”

**********

While they were making First Contact, which was named best documentary feature in Australia, Bob and Robin met another of Mick Leahy’s sons: Joe Leahy, a 40-something coffee planter.

Joe’s mother was a woman from the Jiga tribe—“a stone-age woman,” he liked to say—who died when he was a toddler. Mick never acknowledged him, so Joe was raised by his mother’s clan, where he never quite fit in. His skin was lighter, his hair finer, never able to hold ceremonial feathers. His uncle Danny, who started growing coffee when the gold petered out, took Joe in when he was a teenager and taught him the coffee business, starting him on the labor line and making him work his way up.

By the time Bob and Robin met him, Joe had his own plantation, Kilima, and was one of the wealthiest men in the Nebilyer Valley. He owned property in Mount Hagen and drove a Range Rover and lived in a sturdy house of concrete blocks with a veranda and a formal dining room and a giant satellite dish in the front yard. He’d bought his land cheap from a big man of the Ganiga tribe named Tumul, and his labor came mostly from Ganiga tribal people, who lived all around him in grass huts, tending pigs and sweet-potato gardens.

There was no place for Joe in First Contact, which was about events that had taken place half a century earlier. Joe was, however, a product of those very encounters, the embodiment of Papua New Guinea’s jarring introduction to the modern world. “Joe’s mentors were the white, colonial Australians,” Bob says. “He was taught that you never show kindness, because kindness is weakness. You never let these people—you know, these people—get their heads up, and if they do, you knock ’em off.”

That Joe was, by birth, one of those people only complicated matters. Which made him an ideal subject for another film. Though Robin never took to Joe, Bob liked him well enough. “I admired him in a lot of ways,” he says. “I thought he was a man of tremendous strength, tremendous determination. And there was also my complete conviction that, in terms of observational documentary filmmaking, I would never find a better subject. Not just him, but the situation he was in. It’s easy to oversimplify things, but it was this monumental clash of cultures. I gradually realized that this sort of story happens once in your lifetime.”

In 1985, Bob and Robin returned to the highlands to make a new film about Joe Leahy. They stayed 18 months, living in a thatched hut on Joe’s land, lugging around a camera and sound gear, slowly piecing together scenes of an intensifying dispute between Joe and his Ganiga neighbors. With Kilima, Joe was running a capitalist enterprise in a land of communal customs, where the idea that land could be bought and sold, or that wealth could accrue to one man, was inconceivable. In fact, Tumul, the Ganiga big man, had given up his clan’s sweet-potato fields for a pittance because Joe’s knowledge of the white man’s bisnis was supposed to make Tumul’s people rich, too.

“All lies,” Joe fumed about Tumul in Joe Leahy’s Neighbors, which was released in 1989. “I never promised anyone anything.” It’s never quite clear from the film whether Joe really believed that, if this was a misunderstanding or a swindle. Nor does it really matter. The Ganiga wanted their due.

One of the film’s protagonists is a young tribesman named Joseph Madang, who eventually became one of Bob and Robin’s closest friends. “Say he’s made 800,000 profit,” Madang tells Bob’s camera. “Well, now we’d like to make 800,000. He owns it, eh? We own it. He only paid us 600 kina when he bought Kilima. We’re not happy. We’re joint owners. Joe and us. He’s wealthy, now it’s our turn. It’s not fair that one man should earn all the money.”

For more than a year, Bob and Robin filmed Madang’s clandestine attempt to raise money to buy back Kilima. At the same time, they followed Joe as he managed his obligations to his neighbors, dispensing a few kina here and there, offering funeral gifts and manhandling coffee thieves. At one point Joe appeases Tumul with nothing more than a broken-down truck, to the clear dissatisfaction of many of Tumul’s tribespeople.

Finally, after Madang’s effort to raise money collapses, and with the Ganiga increasingly agitated, Joe agrees to start a second plantation, which they call Kaugum, on the nearby land of another Ganiga big man named Popina Mai. Joe will put up the money, the tribe will put in the labor, and the profits will be split between them—60 percent for Joe, who argues he’s taking the financial risk, and 40 percent for 500 Ganiga supplying the land and the labor.

It’s an ending that is at once hopeful and ominous, the promise of a future straddling the precarious line between savvy and naiveté.

**********

Black Harvest, the final film in what became known as the “Highlands Trilogy,” picks up five years later, when Kaugum is flush with its first harvest of fat, ruby coffee cherries. “With good prices, you’ll be up to your necks in money,” Joe had said to Popina Mai, as they stood smiling in a grove of freshly planted coffee trees. “Up to your necks!”

Popina Mai beamed. “My tribe will be rich, and they’ll have us to thank,” he said. “Poor men will be rich, rich men richer.”

When Bob and Robin returned to the highlands and built another hut and planted a new garden—now with a newborn daughter in tow—they expected to make a movie about what the Ganiga would do with their newfound wealth: once Kaugum’s first crop was harvested, pulped, washed and dried, the Ganiga’s 40 percent share would have been worth several hundred thousand dollars.

Then two things happened: the price of coffee on the global market suddenly collapsed—for the Ganiga, a baffling development. What was the point of all that work, of the white man’s bisnis, if it could be obliterated by a distant wraith?

That calamity, however, was quickly compounded by something closer to home: the outbreak of a tribal war, after several women from an allied tribe were raped by enemies from across the valley. The crimes required retaliation, and though the Ganiga were not directly involved, tradition compelled them to join the fight. And Bob and Robin found themselves in the middle of it.

Tribal wars in the highlands were almost theatrical affairs, with battles scheduled for specific times and places—say, a field burned and stomped clear of grass so nobody could stage ambushes—and fought primarily with spears and arrows, big wooden shields and the occasional homemade shotgun. For a time, Bob and Robin were able to carry their gear onto the battlefield itself. There were dozens of casualties. At one point, Joseph Madang, by now one of Bob and Robin’s dearest friends, was outflanked, shot by one of those primitive guns, chopped with steel axes, killed. Bob wept openly at his funeral.

With the men fighting and coffee prices too low to support a good wage, Kaugum’s crop began to rot on the trees, and the film captures Joe vacillating between impotent rage and mounting despair for himself and the Ganiga he views with ambivalence as his wards. It seemed that capitalism and tribalism had conspired against him and the Ganiga both. Almost the entire crop shriveled, turned black. Joe, disgusted and defeated, left for Brisbane, Australia, where he owned land and had already sent his wife and his children to go to school.

At the end of Black Harvest, Popina Mai is devastated. His partner and patron has gone to Australia. His friend Madang is dead. The plantation on which he’d staked his fortune and reputation, which he’d believed would bring his tribe into the modern world, was covered with rotting coffee cherries. In despair, he walked onto the battlefield and waited for an arrow to strike.

And then the camera is on him in a hut, lying on his side. His chest is swollen with blood from an arrow wound. A friend sits at his feet, waving away flies. The room is dressed in shadows and gold light, a Pietà framed in Bob’s camera. “They’ve destroyed my plantation and me,” Popina says. “When the arrows came, I thought about my plantation. I thought about Joe. And then the arrow struck.” He grimaces. “That’s enough. It’s painful to talk.” The camera lingers, then cuts to surrounding coffee fields, empty and ruined.

This is where the “Highlands Trilogy” ends. “So often, other people’s misfortune is a filmmaker’s good fortune,” Bob says now. He lets that hang for a beat. “It’s a terrible thing to say, but it’s true.” The films went on to become documentary classics, still shown in university anthropology and film departments. “They’re landmark films, because they convey the sense of history,” says Alex Golub, an anthropologist at the University of Hawaii, who studies the highlands region. “At the same time, they convey a lot of the nuances that can get lost when you tell a very simple story of cultural contact. There’s a moral ambiguity. They avoid the story of triumphant white development bringing wisdom to the benighted black people, but they also avoid the story of brave indigenous people being crushed by colonialism.”

Not long after the scene in Popina’s hut, Bob and Robin left Kilima for a guesthouse near Mount Hagen. The plantation was a war zone, and they’d filmed what they needed. All that was left was translating dialogue with the help of a Ganiga named Thomas Thyme. One afternoon, a group of Ganiga tribesmen traveled to Mount Hagen, where they found Bob in the market, buying vegetables. They handed him a piece of cane bent into a figure eight. It was a symbol that what they had to say was extremely important: an enemy tribe, the Kulga, was going to kill Bob.

Bob was as dumbfounded as he was frightened. He and Robin had never taken sides. But it turned out Thomas Thyme had bought a gun, and the Kulga assumed that Bob and Robin had given him the money to do so. They assumed this, in part, because they’d heard that Bob had cried after Madang was killed. Robin was safe, as was their toddler daughter. But Bob was on a list of targets.

They couldn’t afford to fly Thomas to Sydney to finish the translations, so Bob borrowed a gun from a friend in the gold trade, which he kept nearby as he slept, and hired a pair of guards armed with axes. They rushed through a few more weeks of work, and then Bob and his family left. He never said goodbye.

**********

There are not a dozen or more Ganiga up at the house. Out back, past the small garden, there are only a few women peeling and cutting starchy vegetables—cassava, taro, plantain, sweet potatoes—and four men heating rocks in a wood fire. A pig snuffles a potato in the shade of a banana tree. “Four thousand kina, that pig,” Joe announces. About $1,200, maybe more. Bob learned years ago that, in the highlands, a pig is a measure of the man who provides it, though in a way Joe’s announcement sounds less like an offering than an accounting.

Joe met Bob in front of the house, by the giant satellite dish that’s now scabbed with rust and no longer linked to a satellite. It was an almost formal greeting, a handshake and hello, a few mutterings about how long it’s been. Joe is not a man given to displays of affection. He is either 77 or 80 years old now—he says both at different points—and he’s lost the thick dark hair with the authoritative gray at the temples. Otherwise, he looks pretty much the same as he did in Bob and Robin’s films, still sturdy from walking miles of Kilima every day.

Bob had never returned before now, he told me, out of fear. “I didn’t want to get my head blown off, to be honest,” he said. “I wasn’t confident they’d forgotten the circumstances under which I’d left.” He stayed in Australia, making documentaries, and wrote a book, Making Black Harvest, a memoir about his experience making that third, fateful film. In 2002, Robin died of cancer. Bob later fell in love with a musician and filmmaker named Sophie Raymond, and in 2015 they had a daughter.

Not long afterward, Bob received an email out of the blue that made him curious enough to brave a return to Kilima. It was from Joshaia Thyme, the son of his former translator, Thomas. Joshaia was living in Port Moresby, the capital on the coast, and was by his account the first Ganiga to graduate from college. He said a second Ganiga, a woman, had also earned a college degree. “Our leaders turned away from tribal fighting,” Joshaia wrote, “and everything is peaceful.”

Was this a story of hope? To find out, in July 2016 Bob teamed up with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation to make a half-hour television report about what had changed since he and Robin left. He also planned to do some scouting on his own to see if there was a fourth film to be made, a larger story about progress.

At the house, Joe leads Bob around to the back. A scrawny dog scuttles away. “I used to have another dog,” Joe says. “Three times, he bit me. So I had a stick. And I said, ‘Now you are biting the boss. This is what you get.’” He pauses, stares at Bob, almost as if he expects Bob to finish the sentence, but Bob does not. “I killed it,” Joe says. He glances at the skinny one. “This one’s a stupid dog.”

“Joe,” Bob tells me later, “I think is just a very damaged guy. When he used to get drunk, it all came out. Bloody white men, bloody kanakas,” he’d say, using the derogatory Australian slang for native laborers. “He hated everyone, and in a way he hated himself. I saw the war break out in him, and I felt infinitely sorry for him.”

And that was when Joe was a rich man, when he managed a small empire like a feudal lord. His house is still standing, but the paper is peeling from the walls, shards of glass hang loose in broken window frames, and a sagging gutter is held up with makeshift poles. The satellite dish that was a monument to his wealth mocks his decline. For years, he lived off what he grew—potatoes and ginger and mandarins and bananas. Even now he does most of his cooking on a wood stove in a shed in the backyard.

For a while after the tribal war started, Joe stayed in Australia, but within a few months he left his wife and three children to come back to what was left of his coffee. About five years ago, when Joe thought he was dying of cancer, he asked his son Jim, by then grown and living in Mount Hagen, to take over the plantation. Jim and his wife put two years and all of their savings into it, pruning trees, rebuilding the factory. They got cherries growing on the old trees again.

Then Joe got better, and he returned, and he kicked them out. He wanted things done his way. The plantation produces a little now, enough to employ a few pickers, which is a hundred or so fewer than when Bob first arrived. Joe’s trying to diversify, planting peanuts and sweet potatoes, and he has 27 pigs, including the one in the shade behind the big house.

When the vegetables are ready and the rocks are hot, the pig is led out to the fire. Then a man named Korapen bashes it in the face with a wooden club, and he keeps bashing it until the pig stops squealing and twitching.

Bob toes the ground, hands in his pockets. “Well,” he says to no one in particular, “that wasn’t so bad.” He looks away. “I’ve certainly seen worse.” The carcass is hefted onto the fire so the hair can be singed off before Joe and the other men butcher it, cleaving it in half lengthwise, then cutting the halves into smaller pieces. The pig and the vegetables are layered in a pit with the hot rocks and covered with banana leaves. The mumu will cook for hours.

**********

A few days later, Bob walks the red-dirt roads of the Nebilyer Valley and locals see him from their gardens and fields and cry out his name. They come to walk with him, a crowd of old friends gathering around him as he moves. Back in the ’80s, when Bob and Robin lived here, they were the only kundulya (white people) most of the highlanders had ever known who weren’t missionaries or bureaucrats.

“You people have held me in your hands,” Bob tells the crowd in his rusty pidgin, “and I’ve held you in my head and in my heart.”

There are warm smiles at that, a cheer. People tell him how sorry they are about Robin. They say how happy they are that he’s returned. They tell him the highlanders have turned away from war, have turned toward God, want to be prosperous and peaceful forevermore.

There is only one awkward moment, and it is not wholly unexpected. “Our documentary film that you’ve made,” a man named Joseph Wagaba begins, “has been telecast around the world, and you’ve received a top award for this as we all know. So the interest, what the people want to know from you, is there some form of compensation or payment that you will make to the community for helping you, for cooperating with you to make this film?”

Bob is under no illusions that the films could have been made without the cooperation of the Ganiga (or Joe), and among the numerous awards the works received was, for Black Harvest, the grand prize at a Japanese film festival in 1993 that was worth about $30,000. And Bob and Robin did believe that the money should be shared with the Ganiga. They deposited half of the proceeds in an account in Mount Hagen, control of which they turned over to Joe, Thomas Thyme and four Ganiga big men who were illiterate and marked the bank papers with an X. Bob and Robin suggested the money should be used for scholarships.

Then it disappeared.

Bob finally confronted Thomas about the disappeared funds a few days before he reached Kilima, in a shopping mall food court in Port Moresby. First Thomas said he’d taken only half of the money, which wasn’t true. He said he wanted to bring power lines into the village, but there wasn’t enough for that, and then he wanted to invest it in Kaugum, but none of the other big men agreed. Instead, he admitted, he spent it all on another rifle and bullets and a plane ticket to go fetch them. There was a war on, he said, and the Ganiga were outgunned.

Few of his tribespeople believe that that accounts for all the money. The consensus is Thomas simply took it. Not stole it—just took it, because, well, it belonged to the tribe and Thomas was part of the tribe.

Back in the highlands, Bob handles Joseph Wagaba’s question deftly. “We sent the money and felt really glad it was going to the Ganiga,” he says. “You alone look after the money. It’s got nothing to do with me. My job was finished. So now I’m happy to come and visit you, but I’m not happy you should be unhappy with me about this issue, which was resolved 25 years ago.”

That seems to settle that matter, for now. The speeches begin, and the talk is of development and business and the future. Joe’s son Jim Leahy is there, and he’s the last to speak, not to Bob but to the highlanders. It’s a stemwinder on work and sweat and learning how to fish, metaphorically, instead of always asking others for their fish. It’s striking how much the scene resembles so many from Bob’s films, when Joe would lecture the highlanders about investing, about bisnis and responsibility. “For 40 years, I’ve been listening to this talk,” Jim says, “but I haven’t seen any action.”

Jim walks off, and the people applaud.

**********

One afternoon, Bob and Joe hike down the long drive from Joe’s house to the field where Joe used to dry his coffee. It’s thick with kunai grass, waist high, swaying in a faint breeze. They cross to a small clearing where Bob and Robin built their houses. Bob points to a spot in the distance where Tumul is buried. Tumul gave Joe his land for a pittance but died before his people saw more than a secondhand truck out of the deal. Bob mentions that Tumul’s family chose that spot so that Joe would have to look at his grave every day.

Joe nods, expressionless. They had a complicated relationship, he and Tumul, and those connections have only grown more knotted with time: Korapen, the pig-killer, is Tumul’s son, one of the few Ganiga that Joe still gets on with.

Farther down the hill is the church, a squat building of plywood and corrugated metal belonging to a fundamentalist Christian denomination to which Joe now adheres. Bob is intrigued by this—Joe certainly did not seem like a religious man 25 years ago—and he takes the opportunity to ask Joe why he turned to Christianity.

“I tried all my traditional ways to make them understand,” Joe says at first, meaning the highlanders, which makes it sound less like a calling than a management tool. Bob pushes again, and Joe digresses into a meandering analogy about Moses wandering the desert. “I’ve become a Moses!” he laughs. Joe seems to mean religion, or at least a proliferation of churches, has finally brought peace to the Nebilyer. Or maybe he means that he’s seen the Promised Land, has led his people to it—but that, like Moses, he’s destined never to dwell there himself. Bob never does get a clearer answer. Joe believes himself to be a righteous man, though his faith does not appear to extend beyond believing that there is a God, and that he probably will not send Joe to hell.

They walk down to the church to contemplate this. Also, to rest, because neither is a young man anymore and Bob’s knee hurts. They sit on a bench in the back, under Christmas garlands hung in July, two old bulls.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen after I die,” Joe says.

“No?”

“I’ll be dead and gone.”

“This was your life’s work, though, wasn’t it? Kilima? You were really proud of the way you built it up,” Bob says.

“Exactly. We built the roads and all these things. But I gotta leave it one day.”

Joe says, there in the church, that he’ll sell Kilima. “Whoever comes with the money, they’ll take it,” he says, meaning the plantation. “It will be a good lesson for the Ganigas, too, because they’re not ready to take over.”

Bob reminds him that it’s not that simple, that for many of the highlanders, land isn’t a fungible commodity. “For them, land is not something you buy and sell,” he says. “They’d just as soon buy and sell their baby, their children. True?”

Joe snorts. “Exactly,” he says. “For money.”

Which, of course, isn’t what Bob meant at all.

**********

A dozen years ago, when Bob published Making Black Harvest, he’d already had a dozen years to think about the events he and Robin captured for posterity. At the end of the book, Bob recalled his last night in Papua New Guinea, terrified for his life, his wife and toddler daughter asleep while he stood guard at the window, a gun stowed nearby. The memory of that gun “is still with me now,” Bob wrote, along with “my black resolve that night to point the thing at someone and shoot them dead if I had to. With that resolve I had broken the rules, betrayed my calling, crossed the line between observer and participant. Never in all my years in New Guinea had I felt such an interloper. We had no business staying in this place any longer, no legitimacy. It was time to go home.”

Today Bob looks back at the time he spent making those films with relish and pride and a healthy dose of nostalgia. “Those 12 years were my personal and professional highlight,” he tells me. “And I confess,” he says, “I think the films are remarkable examples of observational filmmaking.”

But about his role in the history of the place, and where he stands in relation to the line between observer and participant—he’s pretty much finished thinking about that. He did the hard work of reflection long ago, and any suggestion that he was something other than a man with a camera seems to him beside the point. “We tried as hard as we could to be unobtrusive, neutral chroniclers,” Bob says. “Often when filming significant scenes, I used to think to myself that we were documenting historic events in the post-contact history of the tribe. I went further sometimes. ‘This is the stuff of Aeschylus or Sophocles,’ I found myself saying. A great tragedy was unfolding in front of us, and we didn’t have to be great playwrights—all we had to do was be patient, stick it out, keep a low profile, not interfere, stay neutral and get it in focus.

“Most of the tribal people we worked with had had little contact with films or media of any kind,” he goes on. “We never told people what to do or say, never got them to repeat action and scrupulously avoided taking sides—for example, thinking of Joe as the neocolonial exploiter, the Ganiga as colonial victims. Significant events happened all the time, which kept everyone very busy, and we were not considered important in the scheme of things. After a while we really were just part of the furniture, so to speak. I genuinely believe our presence did not influence what unfolded in any significant way.”

If he has any regrets, Bob admits to feeling queasy about how enraptured he was with his work toward the end. “I’m a bit worried by what sort of people we became as the war turned bad,” he says. He mentions filming Popina Mai, wounded by an arrow, and feeling ecstatic about how the scene would play—instead of immediately rushing him to a doctor. (In fact, Bob and Robin did take Popina Mai to a hospital after they shot the scene, and Popina survived the wound and lived a few more years.) “When you lock onto a narrative as compelling as this,” Bob says, “you yield a bit of your humanity to your creative ambition. Despite that, I’m still glad I did keep shooting. So read into that what you want.”

**********

And the future? Bob realized pretty quickly there would be no fourth film. What story was left for him to tell? That once-promising enterprises like Kilima and Kaugum hadn’t recovered after collapsing under their own contradictions? That the Ganigas’ communal culture and Joe’s bisnis hadn’t found a way to coexist, but were still grinding against each other, the way tectonic plates inexorably build pressure until one slips—until a war breaks out, or a commodity price collapses?

Bob and Robin already told those stories, and sadly there has not been enough progress to document in the time since. It’s not only the failure of the plantations—Kilima barely producing, Kaugum surrendered to the green tendrils of the bush. “There’s just been a gradual decline,” Bob says. At the time of his trip, Mount Hagen was like “a coiled spring,” ready to snap, and the Nebilyer Valley had been institutionally abandoned. There was no government presence to speak of. The roads still weren’t paved. The staff at Mount Hagen’s hospital had recently gone on strike after raw sewage leaked into an operating room. There was a new local primary school—the money to build it came from an Australian aid group—but the teacher wasn’t paid for three years, and there were no desks, chairs or books.

And yet Bob saw a fundamental hope in that fact. “That teacher was still there,” he says. “Why? Because he’s a Ganiga, and he had some land and his wife grew some sweet potatoes and that’s all he needed.” And it’s true: despite widespread poverty and a lack of public services or economic opportunity, 75 percent of Papua New Guinea is estimated to be self-sufficient in food and housing. It is a country where the government is largely irrelevant, and the population has learned to fend for itself.

In a way, then, maybe the Nebilyer Valley hasn’t deteriorated so much as simply reverted. Bob and Robin bore witness to Joe’s experiment in globalization only to see it undone by ancient tribalism. By some standards, tribal society would seem to hold back the highlands from modern economic prosperity; but from another perspective, it’s the thing that holds the place together. Communal traditions and customs and the support systems they cultivate, having functioned for millennia, can’t really be dismantled in less than a century, if ever they should be.

“That,” says Bob, “is the salvation of the place.”

All video courtesy of Documentary Educational Resources

First Contact: New Guinea's Highlanders Encounter the Outside World

The story of the extraordinary 1930 encounter between a team of gold prospectors and a pre-technological civilization ignorant of the outside world, as remembered and photographed by those whose lives it changed.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(2336x590:2337x591)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/85/4285ca0d-554a-4cbf-b413-98bd76580e6c/mar2018_c01_papuanewguine-wr.jpg)