The Rescue of Henry Clay

A long-lost painting of the Senate’s Great Compromiser finds a fitting new home in the halls of the U.S. Capitol

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Henry-Clay-portrait-Capitol-631.jpg)

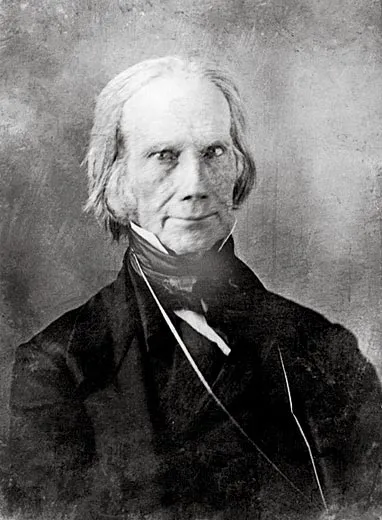

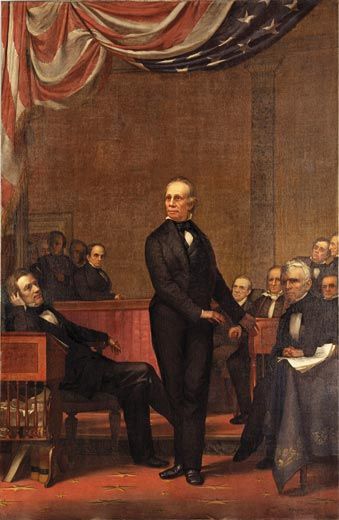

Six brawny movers gingerly made their way out of the LBJ Room in the Senate wing of the U.S. Capitol this past May 24. In their gloved hands, they carried a monumental canvas sheathed in plastic, maneuvering the 100-pound, 11- by 7-foot painting toward a staircase leading from the opulent Brumidi Corridor. Finally, the movers painstakingly removed the packing, revealing a pantheon of larger-than-life senators from the years preceding the Civil War. At the painting's center, towering over his colleagues, stands Kentucky's Henry Clay, careworn and majestic, apparently declaiming with the silver-tongued oratory for which he was famous.

Completed nearly a century and a half ago by Phineas Staunton (1817-67), the painting, Henry Clay in the U.S. Senate, had been all but forgotten and left to molder in a basement in upstate New York. Now, after a 17-month restoration, it has found a home in one of the handsomest settings in the Capitol. "I never thought I'd see this day," says Diane Skvarla, the U.S. Senate curator. "We've not only rediscovered this painting, we've rediscovered its beauty." The portrait was officially unveiled on September 23."Clay deserves this recognition, because he is eternally and deservedly associated with the art of legislative compromise," says Richard Allan Baker, former historian of the U.S. Senate.

Clay's career in Congress spanned nearly 40 years; he served Kentucky with distinction in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, with a four-year detour, beginning in 1825, as secretary of state under John Quincy Adams. He was also five times a contender for the presidency, and thrice a party nominee—in 1824, 1832 and 1844. A founder of the Whig Party, Clay was one of the first major politicians to advocate expansion of federal power. An enlarged role for the government, he believed, would promote the "safety, convenience, and prosperity" of the American people.

Clay's eloquence, wit and mellifluous voice were known to move listeners to tears. Spectators packed the Senate chamber to hear him. "As he set forth proposition after proposition with increasing energy and fire," journalist Oliver Dyer would recall, "his tall form would seem to grow taller and taller with every new statement, until it reached a supernatural height....His eyes flashed and his hair waved wildly about his head; his long arms swept through the air; every lineament of his countenance spoke and glowed, until the beholder might imagine that he saw a great soul on fire."

Clay's political gifts were apparent from the outset. He was a charismatic member of the Kentucky legislature when first appointed to a vacated Senate seat in 1806, at the age of 29—a year younger than the legal threshold of 30. (No one made an issue of it.) In 1811, he ran successfully for the House of Representatives, then regarded as the more important of the two bodies, and was elected speaker on the first day of the session—the only such instance in the nation's history. "The Founders considered the speaker a ‘traffic cop,' " says Robert V. Remini, historian of the U.S. House of Representatives and author of Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union. "Clay made it the most powerful office after the president, controlling legislation, controlling the committees, and making it possible for that body to really get things done." His talent for creative compromise repeatedly drew the nation back from sectional crisis and possible dissolution. In 1820, Missouri's imminent admission to statehood threatened to destabilize the Union. Slavery lay at the crux of the matter. Although a slave owner himself, Clay opposed expansion of bondage on principle. ("I consider slavery as a curse—a curse to the master, a wrong, a grievous wrong to the slave," he later declared.) Nonetheless, he defended slavery as both lawful and crucial to the Southern economy, dismissing advocates of immediate emancipation as "sentimentalists." He professed a belief in gradual emancipation and eventual return of freed slaves to Africa. But he believed in survival of the Union above all.

Missourians had made clear that they intended to enter the Union as a slave state. When the North resisted, the South began to speak of secession, even civil war. Clay brought all his powers of conciliation to bear. "He uses no threats or abuse—but is mild, humble, and persuasive—he begs, instructs, adjures, and beseeches us to have mercy on the people of Missouri," wrote New Hampshire Congressman William Plumer Jr. Those who resisted efforts to achieve compromise, however, experienced Clay's wrath as "continuous peals of thunder, interrupted by repeated flashes of lightning." With Massachusetts' Daniel Webster and South Carolina's John C. Calhoun, Clay crafted an agreement whereby Missouri would be admitted as a slave state balanced by a new free state, Maine. A line would be drawn across the Louisiana Purchase, west of Missouri: states to the north would be admitted as free; those to the south would permit slavery. For his achievement, Clay was praised by admirers in Congress and the press alike as "the great Pacificator" and "a second Washington."

It was during Clay's long Senate career, from 1831 to 1852 with a seven-year hiatus in the 1840s, that he left his deepest imprint. "He was one of the most effective senators in American history," says Baker. "He had vision, intellect, personality—a rare combination." In 1833, Clay was instrumental in defusing confrontation between the federal government and South Carolina, which threatened to "nullify" federal laws of which it didn't approve.

Arguably, Clay's greatest moment on the legislative stage came in 1850, when Southern states seemed on the verge of seceding over California's admission as a free state, tipping the balance in the Senate against the South for the first time. Stooped with age and racked by the tuberculosis that would kill him within two years, the 72-year-old Clay delivered an epic speech that extended over two days. He urged a complex "scheme of accommodation" that would extract concessions from each side. He concluded with a passionate plea for the Union. "I am directly opposed to any purpose of secession, or separation," he declared. "Here I am within it, and here I mean to stand and die. The only alternative is war, and the death of liberty for all." He begged Northerners and Southerners alike "to pause—solemnly to pause—at the edge of the precipice, before the fearful and disastrous leap is taken into the yawning abyss below."

Although Clay himself would collapse from exhaustion before the measures he advocated were enacted, he had created the framework for a visionary compromise. California would be admitted as a free state; to placate the South, the vast Utah and New Mexico territories would not be allowed to bar slavery (or to explicitly legalize it). The slave trade would be ended in Washington, D.C., as abolitionists desired; but a harsh new law would impose severe penalties on anyone daring to aid fugitive slaves, and make it easier for slave owners to recover their human property. "I believe from the bottom of my soul that this measure is the reunion of this Union," Clay asserted.

At the time, the compromise was widely hailed as a definitive settlement of the slavery question. Of course it was not. But it did stave off secession for another decade. "If Clay had been alive in 1860, there would have been no civil war," says Remini. "He would have come up with a detailed package of issues. He always seemed to know just the right thing to do. He understood that each side must gain something and lose something—that no one can get all the marbles."

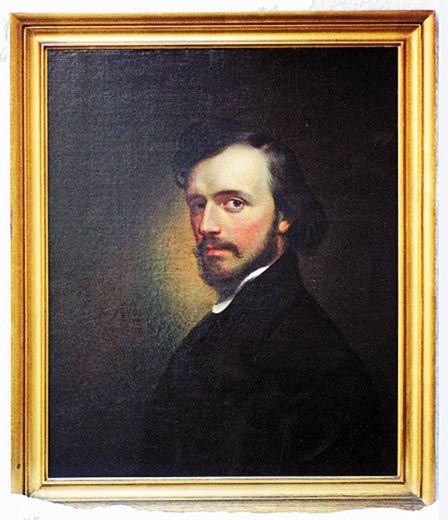

Although Phineas Staunton, who had trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, in Philadelphia, had once met Clay, the painter would not create the senator's portrait until 1865, when he entered a competition to memorialize Clay announced by the State of Kentucky. Staunton depicted Clay in the midst of the Compromise of 1850 debate. Staunton failed to win by a 4-to-3 vote of the judges. (Rumor had it that Staunton's inclusion of Northern senators had dashed his success.)

The painting was shipped back to Staunton's hometown, Le Roy, New York, near Rochester. Meanwhile, Staunton had signed on as an illustrator with a fossil-collecting expedition to South America sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution. He succumbed to tropical fever in Ecuador in September 1867 at age 49.

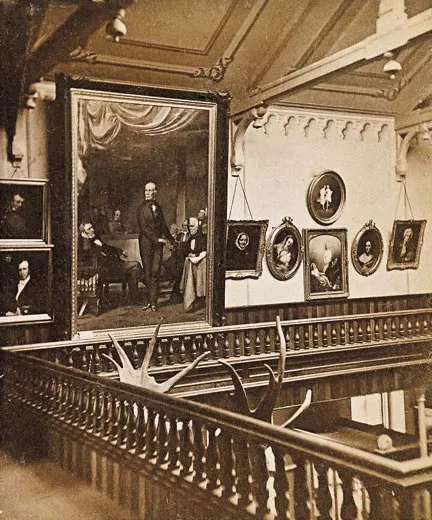

Until 1901, Henry Clay in the U.S. Senate hung in an art conservatory in Le Roy, and then for decades in a local public school, where Clay served as a target for peashooters, spitballs and basketballs, which left a moonscape of dents and tears on the canvas. In the 1950s, the painting was consigned to the basement of the Le Roy Historical Society's warehouse, amid carriages, cast-iron stoves and a 1908 Cadillac. Then, in January 2006, Lynne Belluscio, the society's director, received a call from Amy Elizabeth Burton, an art historian in the office of the U.S. Senate curator. Burton had learned of the painting from a descendant of Staunton. Did the society possess a portrait showing Clay in the Senate?

Burton was soon on a plane to Le Roy. There she found the canvas, cracked, flaking and so filthy that many figures were unrecognizable. "It was covered with grime," recalls Burton. "It was torn, it had blobs on it. But Clay's face shone out with that fateful gaze of his. All I could think of was, ‘Oh, my word, it's an art historian's dream come true!'" The painting's significance was immediately apparent: it is one of only a handful of works documenting the Old Senate Chamber, which, after expansion of the Capitol in 1859, was occupied by the Supreme Court until 1935. Would the Historical Society, Burton asked, ever consider parting with Staunton's work? "It took about a nanosecond," Belluscio recalls, "to say yes."

Restoration began in January 2008 and was completed this past May. "It was one of the largest paintings in the worst condition that I ever saw—maybe the worst," says Peter Nelsen, a senior conservator with Artex, a Landover, Maryland, restoration firm. "It looked as if it had been buried." Sections as small as one square inch had to be repaired, one at a time, 11,000 square inches in all. "It was the most challenging painting that we ever worked on," Nelsen adds. "It kept me awake at night with anxiety."

Gradually, figures began to emerge from the background: the legendary orator Daniel Webster; abolitionist William Henry Seward; blustering Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri; and Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, the "Little Giant" who finalized the 1850 compromise after the senator from Kentucky collapsed. At the center stood Clay, his face transfigured by Staunton with an unearthly radiance.

What, one wonders, would Clay make of the heated exchanges that occur across the aisle in Congress today? "Our discourse pales with comparison to the early history of the country," says Senator Mitch McConnell, a lifelong admirer of his Kentucky predecessor. For 14 years, McConnell sat at Clay's Senate desk. (Kentucky's junior senator, Jim Bunning, currently occupies it.) "The compromises he wrought were life and death issues for the nation, at a time when not everyone was sure the nation would last. If you are going to be able to govern yourself, you have to learn to compromise. You can either get something, or get nothing; if you want to get something, you have to compromise."

Senator Charles E. Schumer of New York concurs. "Henry Clay's talent repeatedly drew us back from the brink of calamity," he says. "The hanging of Clay's painting couldn't come at a more symbolic time. I hope it will be a reminder to all of us in the Senate that bipartisan agreement can help push us toward becoming a more prosperous nation."

Frequent contributor Fergus M. Bordewich's most recent book is Washington: The Making of the American Capital.