The Shock of War

World War I troops were the first to be diagnosed with shell shock, an injury – by any name – still wreaking havoc

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Shellshock-World-War-I-British-troops-Battle-of-Arras-631.jpg)

In September 1914, at the very outset of the great war, a dreadful rumor arose. It was said that at the Battle of the Marne, east of Paris, soldiers on the front line had been discovered standing at their posts in all the dutiful military postures—but not alive. “Every normal attitude of life was imitated by these dead men,” according to the patriotic serial The Times History of the War, published in 1916. “The illusion was so complete that often the living would speak to the dead before they realized the true state of affairs.” “Asphyxia,” caused by the powerful new high-explosive shells, was the cause for the phenomenon—or so it was claimed. That such an outlandish story could gain credence was not surprising: notwithstanding the massive cannon fire of previous ages, and even automatic weaponry unveiled in the American Civil War, nothing like this thunderous new artillery firepower had been seen before. A battery of mobile 75mm field guns, the pride of the French Army, could, for example, sweep ten acres of terrain, 435 yards deep, in less than 50 seconds; 432,000 shells had been fired in a five-day period of the September engagement on the Marne. The rumor emanating from there reflected the instinctive dread aroused by such monstrous innovation. Surely—it only made sense—such a machine must cause dark, invisible forces to pass through the air and destroy men’s brains.

Shrapnel from mortars, grenades and, above all, artillery projectile bombs, or shells, would account for an estimated 60 percent of the 9.7 million military fatalities of World War I. And, eerily mirroring the mythic premonition of the Marne, it was soon observed that many soldiers arriving at the casualty clearing stations who had been exposed to exploding shells, although clearly damaged, bore no visible wounds. Rather, they appeared to be suffering from a remarkable state of shock caused by blast force. This new type of injury, a British medical report concluded, appeared to be “the result of the actual explosion itself, and not merely of the missiles set in motion by it.” In other words, it appeared that some dark, invisible force had in fact passed through the air and was inflicting novel and peculiar damage to men’s brains.

“Shell shock,” the term that would come to define the phenomenon, first appeared in the British medical journal The Lancet in February 1915, only six months after the commencement of the war. In a landmark article, Capt. Charles Myers of the Royal Army Medical Corps noted “the remarkably close similarity” of symptoms in three soldiers who had each been exposed to exploding shells: Case 1 had endured six or seven shells exploding around him; Case 2 had been buried under earth for 18 hours after a shell collapsed his trench; Case 3 had been blown off a pile of bricks 15 feet high. All three men exhibited symptoms of “reduced visual fields,” loss of smell and taste, and some loss of memory. “Comment on these cases seems superfluous,” Myers concluded, after documenting in detail the symptoms of each. “They appear to constitute a definite class among others arising from the effects of shell-shock.”

Early medical opinion took the common-sense view that the damage was “commotional,” or related to the severe concussive motion of the shaken brain in the soldier’s skull. Shell shock, then, was initially deemed to be a physical injury, and the shellshocked soldier was thus entitled to a distinguishing “wound stripe” for his uniform, and to possible discharge and a war pension. But by 1916, military and medical authorities were convinced that many soldiers exhibiting the characteristic symptoms—trembling “rather like a jelly shaking”; headache; tinnitus, or ringing in the ear; dizziness; poor concentration; confusion; loss of memory; and disorders of sleep—had been nowhere near exploding shells. Rather, their condition was one of “neurasthenia,” or weakness of the nerves—in laymen’s terms, a nervous breakdown precipitated by the dreadful stress of war.

Organic injury from blast force? Or neurasthenia, a psychiatric disorder inflicted by the terrors of modern warfare? Unhappily, the single term “shell shock” encompassed both conditions. Yet it was a nervous age, the early 20th century, for the still-recent assault of industrial technology upon age-old sensibilities had given rise to a variety of nervous afflictions. As the war dragged on, medical opinion increasingly came to reflect recent advances in psychiatry, and the majority of shell shock cases were perceived as emotional collapse in the face of the unprecedented and hardly imaginable horrors of trench warfare. There was a convenient practical outcome to this assessment; if the disorder was nervous and not physical, the shellshocked soldier did not warrant a wound stripe, and if unwounded, could be returned to the front.

The experience of being exposed to blast force, or being “blown-up,” in the phrase of the time, is evoked powerfully and often in the medical case notes, memoirs and letters of this era. “There was a sound like the roar of an express train, coming nearer at tremendous speed with a loud singing, wailing noise,” recalled a young American Red Cross volunteer in 1916, describing an incoming artillery round. “It kept coming and coming and I wondered when it would ever burst. Then when it seemed right on top of us, it did, with a shattering crash that made the earth tremble. It was terrible. The concussion felt like a blow in the face, the stomach and all over; it was like being struck unexpectedly by a huge wave in the ocean.” Exploding at a distant 200 yards, the shell had gouged a hole in the earth “as big as a small room.”

By 1917, medical officers were instructed to avoid the term “shell shock,” and to designate probable cases as “Not Yet Diagnosed (Nervous).” Processed to a psychiatric unit, the soldier was assessed by a specialist as either “shell shock (wound)” or “shell shock (sick),” the latter diagnosis being given if the soldier had not been close to an explosion. Transferred to a treatment center in Britain or France, the invalided soldier was placed under the care of neurology specialists and recuperated until discharged or returned to the front. Officers might enjoy a final period of convalescence before being disgorged back into the maw of the war or the working world, gaining strength at some smaller, often privately funded treatment center—some quiet, remote place such as Lennel House, in Coldstream, in the Scottish Borders country.

The Lennel Auxiliary Hospital, a private convalescent home for officers, was a country estate owned by Maj. Walter and Lady Clementine Waring that had been transformed, as had many private homes throughout Britain, into a treatment center. The estate included the country house, several farms, and woodlands; before the war, Lennel was celebrated for having the finest Italianate gardens in Britain. Lennel House is of interest today, however, not for its gardens, but because it preserved a small cache of medical case notes pertaining to shell shock from the First World War. By a savage twist of fate, an estimated 60 percent of British military records from World War I were destroyed in the Blitz of World War II. Similarly, 80 percent of U.S. Army service records from 1912 to 1960 were lost in a fire at the National Personnel Records Office in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1973. Thus, although shell shock was to be the signature injury of the opening war of the modern age, and although its vexed diagnostic status has ramifications for casualties of Iraq and Afghanistan today, relatively little personal medical data from the time of the Great War survives. The files of the Lennel Auxiliary Hospital, however, now housed in the National Archives of Scotland, had been safeguarded amid other household clutter in the decades after the two world wars in a metal box in the Lennel House basement.

In 1901, Maj. Walter Waring, a distinguished officer and veteran of the Boer War and a Liberal MP, had married Lady Susan Elizabeth Clementine Hay and brought her to Lennel House. The major was in uniform for most of the war, on duty in France, Salonika and Morocco, and it was therefore Lady Clementine who had overseen the transformation of Lennel House into a convalescent home for neurasthenic soldiers. The daughter of the 10th Marquess of Tweeddale, “Clemmie,” as she was known to her friends, was 35 years old in 1914. She is fondly recalled by her grandson Sir Ilay Campbell of Succoth and his wife, Lady Campbell, who live in Argyll, as “a presence” and great fun to be with—jolly and amusing and charming. A catalog of Lady Clementine’s correspondence, in Scotland’s National Archives, gives eloquent evidence of her charm, referencing an impressive number of letters from hopeful suitors, usually young captains, “concerning their relationship and possible engagement.”

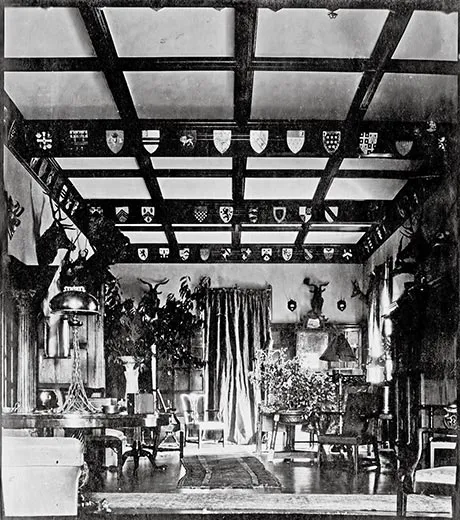

Generally arriving at Lennel from treatment centers in London and Edinburgh, convalescing officers were received as country house guests. A handsome oak staircase dominated Lennel’s entry hall and led under an ornate glass dome to the upper floor, where each officer found his own pleasant bedroom, with windows opening onto the garden or with views of the woodlands and the Cheviot Hills beyond; there appear to have been only about a dozen residents at any one time. Downstairs, the private study of Major Waring had been appropriated during his absence to the war as an officers’ mess, while his paneled library was available to the bookish: Siegfried Sassoon, who was to emerge as one of the outstanding poet chroniclers of the war, found here “a handsome octavo edition” of a Thomas Hardy novel, and spent a rainy day carefully trimming its badly cut pages. Meals were presided over by the officers’ hostess, the beautiful, diminutive Lady Clementine.

Their common status as officers notwithstanding, the men came from many backgrounds. Lt. R. C. Gull had been educated at Eton, Oxford and Sandhurst before receiving his commission in November 1914, for example, while Lieutenant Hayes, of the Third Royal Sussex Regiment, had been born in London, educated in England and Switzerland, and had emigrated to Canada, where he had been engaged in “Business & Farming” before the war. The officers had been Australian station managers, chartered accountants, partners in banking firms and, intriguingly, “a trader and explorer in Central Africa.” The men had seen action in many campaigns, on many fronts, including the Boer War. A number had served at Gallipoli, and all too many had been injured on the Western Front.

Life at Lennel was conducted in the familiar and subtly strict routine of the well-run country house, with meals at set times, leisurely pursuits and tea on the terrace. Lady Clementine’s family mixed freely with the officer guests, her youngest daughter, “Kitty,” who was only 1 year old when the war broke out, being a special favorite. Kept busy throughout the day with country walks, chummy conversation, piano playing, table tennis, fishing, golfing and bicycling, and semiformal meals, each officer nonetheless retired at night to his private room and here confronted, starkly and alone, the condition that had brought him this peaceful interlude in the first place.

“Has vivid dreams of war episodes—feels as if sinking down in bed”; “Sleeping well but walks in sleep: has never done this before: dreams of France”; “Insomnia with vivid dreams of fighting”; and “Dreams mainly of dead Germans...Got terribly guilty conscience over having killed Huns.”

The terse medical case notes, averaging some three pages per patient, introduce each officer by name and age, cite his civilian address as well as regiment and service details, and include a brief section for “Family History,” which typically noted whether his parents were still alive, any familial history of nervous disorders and if a brother had been killed in the war. Education, professional life and an assessment of the officer’s temperament before his breakdown were also duly chronicled. Captain Kyle, for example, age 23 and in service for three years and three months at the time of admittance to Lennel had previously been a “Keen athlete, enjoyed life thoroughly, no nerves.” Brigadier General McLaren had also been “Keen on outdoor sports”—always the benchmark of British mental health—but had “Not very many friends.”

Many treatments abounded for the neurasthenic soldier. The most notorious were undoubtedly Dr. Lewis Yealland’s electric shock therapies, conducted at the National Hospital for Paralysed and Epileptic, at Queen Square, London, where he claimed his cure “had been applied to upwards of 250 cases” (an unknown number of which were civilian). Yealland asserted that his treatment cured all the most common “hysterical disorders of warfare”—the shaking and trembling and stammering, the paralysis and disorders of speech—sometimes in a single suspect half-hour session. Electric heat baths, milk diets, hypnotism, clamps and machines that mechanically forced stubborn limbs out of their frozen position were other strategies. As the war settled in, and shell shock—both commotional and emotional—became recognized as one of its primary afflictions, treatment became more sympathetic. Rest, peace and quiet, and modest rehabilitative activities became the established regimen of care, sometimes accompanied by psychotherapy sessions, the skillful administration of which varied from institution to institution and practitioner to practitioner.

While the officers at Lennel were clearly under medical supervision, it is not evident what specific treatments they received. Lady Clementine’s approach was practical and common-sensical. She was, according to her grandson Sir Ilay, an early advocate of occupational therapy—keeping busy. Painting, in particular, seems to have been encouraged, and a surviving photograph in a family album shows Lennel’s mess hall ringed with heraldic shields, each officer having been instructed by Lady Clementine to paint his family coat of arms. (And if they didn’t have one? “I expect they made one up,” Sir Ilay recalled, amused.) But beyond the nature of the men’s treatment, of course, was the larger, central, burning question of what, really, was the matter.

The symptoms recorded in the case notes, familiar from literature of the time, are clear enough: “palpitations—Fear of fainting...feeling of suffocation, of constriction in throat”; “Now feels worn out & has pain in region of heart”; “Depression—Over-reaction—Insomnia—Headaches”; nervousness, lassitude, being upset by sudden noise”; “Patient fears gunfire, death and the dark...In periods of wakefulness he visualizes mutilations he has seen, and feels the terror of heavy fire”; “Depressed from incapacity to deal with easy subjects & suffered much from eye pain.” And there is the case of Second Lieutenant Bertwistle, with two years of service in the 27th Australian Infantry, although only 20 years of age, whose face wears a “puzzled expression” and who exhibits a “marked defect of recent and remote memory.” “His mental content appears to be puerile. He is docile,” according to the records that accompanied him from the Royal Victoria Military Hospital in Netley, on England’s south coast.

The official Report of the War Office Committee of Enquiry Into “Shell-Shock” made at war’s end gravely concluded that “shell-shock resolves itself into two categories: (1) Concussion or commotional shock; and (2) Emotional shock” and of these “It was given in evidence that the victims of concussion shock, following a shell burst, formed a relatively small proportion (5 to 10 per cent).” The evidence about damage from “concussion shock” was largely anecdotal, based heavily upon the observations of senior officers in the field, many of whom, veterans of earlier wars, were clearly skeptical of any newfangled attempt to explain what, to their mind, was simple loss of nerve: “New divisions often got ‘shell shock’ because they imagined it was the proper thing in European warfare,” Maj. Pritchard Taylor, a much-decorated officer, observed. On the other hand, a consultant in neuropsychiatry to the American Expeditionary Force reported a much higher percentage of concussion shock: 50 percent to 60 percent of shell shock cases at his base hospital stated they had “lost consciousness or memory after having been blown over by a shell.” Unfortunately, information about the circumstances of such injuries was highly haphazard. In theory, medical officers were instructed to state on a patient’s casualty form whether he had been close to an exploding shell, but in the messy, frantic practice of processing multiple casualties at hard-pressed field stations, this all-important detail was usually omitted.

Case notes from Lennel, however, record that a remarkable number of the “neurasthenic” officers were casualties of direct, savage blast force: “Perfectly well till knocked over at Varennes...after this he couldn’t sleep for weeks on end”; “He has been blown up several times—and has lately found his nerve was getting shaken.” In case after case, the officer is buried, thrown, stunned, concussed by exploding shells. Lieutenant Graves had gone straight from Gallipoli “into line & through Somme.” In fighting around Beaumont Hamel in France, a shell had landed “quite close & blew him up.” Dazed, he was helped to the company dugout, after which he “Managed to carry on for some days,” although an ominous “Weakness of R[ight] side was developing steadily.” Ironically, it was precisely the soldier’s ability “to carry on” that had aroused skepticism over the real nature of his malady.

The extent to which blast force was responsible for shell shock is of more than historic interest. According to a Rand Corporation study, 19 percent of U.S. troops sent to Iraq and Afghanistan, about 380,000, may have sustained brain injuries from explosive devices—a fact that has prompted comparisons with the British experience at the Somme in 1916. In 2009, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) made public the results of a two-year, $10 million study of the effects of blast force on the human brain—and in doing so, not only advanced the prospect of modern treatment but cast new light on the old shell shock conundrum.

The study revealed that limited traumatic brain injury (TBI) may manifest no overt evidence of trauma—the patient may not even be aware an injury has been sustained. Diagnosis of TBI is additionally vexed by the clinical features—difficulty concentrating, sleep disturbances, altered moods—that it shares with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a psychiatric syndrome caused by exposure to traumatic events. “Someone could have a brain injury and be looking like it was PTSD,” says Col. Geoffrey Ling, the director of the DARPA study.

Differentiation between the two conditions—PTSD and TBI, or the “emotional” versus “commotional” puzzle of World War I—will be enhanced by the study’s most important find: that at low levels the blast-exposed brain remains structurally intact, but is injured by inflammation. This exciting prospect of a clinical diagnosis was presaged by the observation in World War I that spinal fluid drawn from men who had been “blown up” revealed changes in protein cells. “They were actually pretty insightful,” Ling says of the early medics. “Your proteins, by and large, are immunoglobulins, which basically are inflammatory. So they were ahead of their time.”

“You can never tell how a man is going to do in action,” a senior officer had observed in the War Office Committee report of 1922, and it was this searing truth of self-discovery that the patients at Lennel feared. They were betrayed by the stammering and trembling they could not control, the distressing lack of focus, their unmanly depression and lassitude. No list of clinical symptoms, such as the written records preserve, can do justice to the affliction of the shellshocked patient. This is more effectively evoked in the dreadful medical training films of the war, which capture the discordant twitching, uncontrollable shaking and haunting vacant stares. “Certainly one met people who were—different,” Sir Ilay recalled gently, speaking of damaged veterans he had seen as a boy, “and it was explained of their being in the war. But we were all brought up to show good manners, not to upset.”

Possibly, it was social training, not medical, that enabled Lady Clementine to assist and solace the damaged men who made their way to Lennel. If she was unsettled by the sights and sounds that filled her home, she does not seem to have let on. That she and her instinctive treatment were beneficial is evident from what is perhaps the most remarkable feature of the Lennel archive—the letters the officers wrote to their hostess upon leaving.

“I am quite unable adequately to express my gratitude to you for your kindness and hospitality to me,” wrote Lieutenant Craven, as if giving thanks for a pleasant weekend in the country. Most letters, however, run to several pages, their eager anecdotes and their expressions of anxieties and doubt give evidence of the sincerity of the writer’s feeling. “I got such a deep breath of ‘Lennel,’ while I was reading your letter,” wrote one officer from the Somme in December 1916, “& I’ll bet you had your tennis shoes on, & no hat, & a short skirt, & had probably just come in from a walk across the wet fields”; “Did you really and truly mean that I would be welcome at Lennel if I ever get the opportunity for another visit?” one officer asked yearningly.

A number of the letters are written from hotels while awaiting the results of medical boards. Most hoped for light duty—the dignity of continued service but without the dreaded liabilities. “The Medical Board sent me down here for two months light duty after which I must return to the fray!” writes Lieutenant Jacob, and, as a wistful postscript; “Did you ever finish that jolly Japanese puzzle picture?!” For some, the rush of the outside world came at them too fast: “I have been annoyed quite a lot at little things & my stammer has returned,” one officer confided. Several write from other hospitals; “I had not the remotest idea of how & when I came here,” Lieutenant Spencer wrote to Lady Clementine. “I do not know what really happened when I took ill but I do sincerely hope that you will forgive me if I was the cause of any unpleasant situation or inconvenience.”

At war’s end, the legions of shellshocked veterans dispersed into the mists of history. One catches glimpses of them, however, through a variety of oblique lenses. They crop up in a range of fiction of the era, hallucinating in the streets of London, or selling stockings door to door in provincial towns, their casual evocation indicating their familiarity to the contemporary reader.

Officially they are best viewed in the files of the Ministry of Pensions, which had been left with the care of 63,296 neurological cases; ominously, this number would rise, not fall, as the years passed, and by 1929—more than a decade after the conclusion of the war—there were 74,867 such cases, and the ministry was still paying for such rehabilitative pursuits as basket making and boot repairing. An estimated 10 percent of the 1,663,435 military wounded of the war would be attributed to shell shock; and yet study of this signature condition—emotional, or commotional, or both—was not followed through in the postwar years.

Following the Great War, Major Waring served as Parliamentary private secretary to Winston Churchill. For her work at Lennel House, Lady Clementine was made a Commander of the British Empire. She died in 1962, by which time the letters and papers of her war service were stored in the Lennel House basement; there may be other country houses throughout Britain with similar repositories. Lennel House itself, which the family sold in the 1990s, is now a nursing home.

The fate of some officers is made evident by Lady Clementine’s correspondence: “Dear Lady Waring...my poor boys death is a dreadful blow and I cant realize that he has gone forever....Oh it is too cruel after waiting three long weary years for him to come home.” Very occasionally, too, it is possible to track an officer through an unrelated source. A photograph that had been in the possession of Capt. William McDonald before he was killed in action in France, in 1916, and which is now archived in the Australian War Memorial, shows him gathered with other officers on the Lennel House steps, with Lady Clementine. Some later hand has identified among the other men “Captain Frederick Harold Tubb VC, 7th Battalion of Longwood,” and noted that he died in action on 20 September 1917; this is the same “Tubby” who had written to Lady Clementine a month earlier, at the completion of an 11-hour march, heading his letter simply “In the Field”: “An aeroplane tried to shoot us last night with a m[achine] gun besides dropping sundry bombs around. It rained a heavy storm last night. It is raining off an[d] on today. The weather is warm though. My word the country round here is magnificent, the splendid wheat crops are being harvested....”

Caroline Alexander’s latest book is The War That Killed Achilles: The True Story of Homer’s Iliad and the Trojan War.