The Speech That Saved Teddy Roosevelt’s Life

Campaigning for president, Roosevelt was spared almost certain death when 50 pieces of paper slowed an assailant’s bullet headed for his chest

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/National-Treasure-Assassination-Roosevelt-speech-631.jpg)

On October 14, 1912, just after eight o’clock in the evening, Theodore Roosevelt stepped out of the Hotel Gilpatrick in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and into an open car waiting to take him to an auditorium where he would deliver a campaign speech. Although he was worn out and his voice nearly gone, he was still pushing hard to win an unprecedented third term in the White House. He had left politics in 1909, when his presidency ended. But his disappointment in the performance of William Howard Taft, his chosen successor, was so great that in 1912 he formed the National Progressive Party (better known as the Bull Moose Party). He was running against Taft and the Republicans, the Democrats’ Woodrow Wilson and the Socialist ticket headed by Eugene Debs.

The Bull Moose himself campaigned in more states (38) than any of his opponents. On October 14, he began his day in Chicago, and headed to Racine, Wisconsin, before pressing on to Milwaukee.

When Roosevelt departed the Gilpatrick, he was wearing his Army overcoat and carrying a 50-page speech—folded double to fit into the breast pocket where he had also tucked his metal spectacles case. A stretch of sidewalk had been cleared to speed his walk to the car. As Roosevelt was settling into the back seat, a roar went up from the crowd when they saw him. At the moment he stood to wave his hat in thanks, a man four or five feet away fired a Colt .38 revolver at Roosevelt’s chest.

The assailant, John Schrank, an unemployed saloonkeeper, was tackled and quickly taken away. TR asked the driver to head for the auditorium. His companions protested, but Roosevelt held firm. “I am going to drive to the hall and deliver my speech,” he said.

Having handled guns as a hunter, a cowboy and an officer during the Spanish-American War, Roosevelt knew enough to put a finger to his lips to see if he was bleeding from the mouth. When he saw that he was not, he concluded that the bullet had not entered his lung.

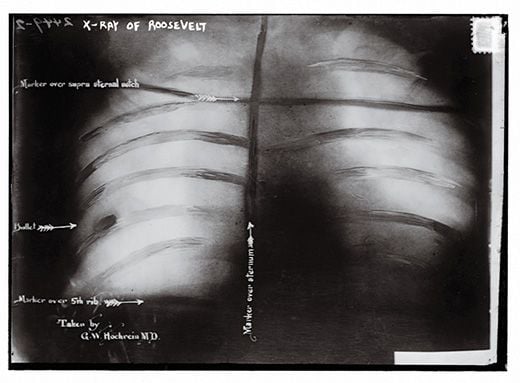

An examination by three doctors backstage at the auditorium revealed that the bullet had been slowed by the thick manuscript and the spectacles case. But there was a dime-size hole in his chest, below his right nipple, and a fist-size stain on his shirt. He requested a clean handkerchief to cover the wound and headed for the stage, where one of his bodyguards attempted to explain the situation to the audience. When someone shouted, “Fake!” Roosevelt stepped forward to show the crowd his shirt and the bullet holes in the manuscript. “Friends,” he said, “I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot—but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.”

Pale and not entirely steady on his feet, Roosevelt spoke slowly but with conviction. Roosevelt warned that if government neglected the well-being of all its citizens, violence of the sort that had just befallen him would become commonplace. “The poor man as such will be swayed by his sense of injury against the men who try to hold what they have improperly won” and “the most awful passions will be let loose.”

As he continued, TR followed his practice of dropping each page when he finished reading it. Journalists often took a leaf or two as souvenirs; on this occasion, Samuel Marrs, a Chicago photographer, scooped up the bullet-pierced page seen here. (The Smithsonian National Museum of American History acquired it in 1974 from his nephew.)

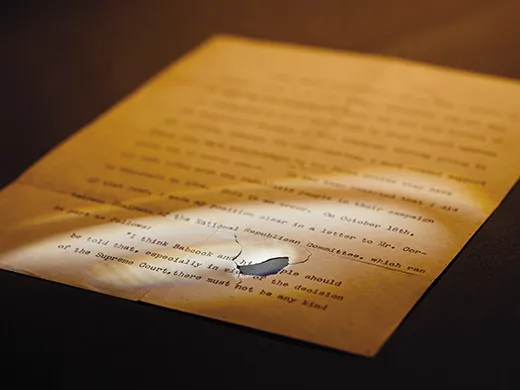

Half an hour into the speech, Roosevelt’s campaign manager walked to his side and put a hand on his arm. Roosevelt looked at him sternly and told the crowd, “My friends are a little more nervous than I am.” He went on for another 50 minutes. Once offstage, Roosevelt agreed to go to the hospital, where X-rays determined that the bullet had lodged in a rib. It would remain there for the rest of his life.

Roosevelt was well enough to resume his campaign one week before Election Day, but on November 5, voters handed the victory to Wilson.

Schrank believed that he was acting on orders from the ghost of President William McKinley, whose assassination in 1901 had made Roosevelt president. After examination by five court-appointed psychiatrists, Schrank was committed to an insane asylum in Wisconsin, where he died in 1943.

When asked how he could give a speech with a fresh bullet wound in his chest, Roosevelt later explained that after years of expecting an assassin, he hadn’t been surprised. Like the frontiersmen and soldiers he admired, he was determined not to wilt under attack. As he put it to his English friend Sir Edward Grey, “In the very unlikely event of the wound being mortal I wished to die with my boots on.”