The Top 10 Political Conventions That Mattered the Most

As the two parties shift their conventions to be mostly virtual, we look at those conventions that made a difference in the country’s political history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/60/f060eff5-76ee-42cc-86af-2db2178c6640/gettyimages-551888207.jpg)

Will there be a virtual balloon-drop? That is about the only intrigue left when it comes to what will happen at this year’s national political conventions. Even more so than usual, the chance for high drama at the twin events is largely zero. Not just because both the Democrats and the Republicans have chosen their candidates, but because both will mostly be held remotely in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

These events, presented entirely over cable news, streaming services, YouTube and social media, with limited network television coverage, will be at the same time boring and unprecedented. Conventions began out of resistance to the existing “caucus system,” in which nominees were chosen in secret by party members in Congress. Once the scene of bare-knuckle politicking and backroom deals, the modern conventions now provide comforting tableaus—full of sound and fury, but mostly signifying nothing.

Since primary elections now routinely determine the candidates, rather than being chosen by the party faithful at the convention, these quadrennial dog-and-pony shows offers ho-hum pageantry in which windy speeches are delivered and party platforms hammered out and often ignored. Thankfully missing this year will be delegates donning silly hats and holding up handmade signs extolling the virtues of candidates, causes and home states. (Though never underestimate the appeal of nostalgia finding a way.)

In 2012, I wrote the piece below detailing this history and more, particularly how the evolving primary process has eliminated the convention as a scene of a battle for a nomination. The convention had essentially become obsolete by the 1972 Democratic Convention in Miami. Following the party reforms of the early 1970s, state primary elections could provide enough delegates to choose the nominee. Senator George McGovern—who had helped write the Democratic Party’s new nominating rules—garnered a majority of Democratic delegates by the time the convention began. (McGovern was then crushed by Nixon in a landslide.) So we may never again have a repeat of 1924, when the Democrats took 17 days and 103 ballots in the longest convention ever to nominate John W. Davis –who was and remains an obscure congressman from West Virginia.

But once upon a time, conventions mattered. They chose the candidates, often with plenty of intrigue and horse-trading in the notorious “smoke-filled rooms” of yesteryear. And for that reason, some memorable conventions have changed the course of history. The 2020 conventions, for that matter, may be historic in their own way in that they signal a last hurrah for a venerable political spectacle.

In Milwaukee, the Democrats will have only a rump of delegates attending and completing official business. On each of the four nights, starting next week, the party delegates will cast their votes and, unless something truly unprecedented happens, will nominate Joe Biden for president. Virtual speeches will come from the nominee, vice presidential nominee Kamala Harris, the Obamas, other party luminaries, and former Republican governor of Ohio John Kasich.

The Republican convention, meanwhile, is back in its original location of Charlotte, North Carolina, after President Trump and the Republican National Committee attempted to move the main events to Florida to avoid COVID-19 restrictions on crowd size. The spike in cases in the Sunshine State, and throughout the rest of the country, has led to much uncertainty as to the convention’s agenda. Most recently, Trump suggested that he might deliver his acceptance speech at Gettysburg National Military Park or a location in Washington, D.C.

To the original list of conventions below that were included for their historic significance, two more recent landmarks should be added. In 2008, Democrat Barack Obama became the first African American nominee of a major party, then winning the first of two terms; his acceptance speech in an outdoor stadium drew a record 84,000 people. And in 2016, Hillary Clinton became the first woman nominated for president by a major party. Despite her victory in the national popular vote, she lost the election in the Electoral College. Below is the original list of 10.

1. 1831 Anti-Masonic Convention—Why start with one of the most obscure third parties in American history? Because they invented nominating conventions. The Anti-Masons, who feared the growing political and financial power of the secret society of Freemasons, formed in upstate New York; among their members was future president Millard Fillmore.

Before the Anti-Masons met in Baltimore in September 1831, candidates for president were chosen in the Congressional caucuses of two major parties –then the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans (soon to be the Democratic Party). In December 1831, the short-lived National Republican party followed the Anti-Mason lead and met in Baltimore to nominate Henry Clay, the powerful Kentucky congressman. The Democrats followed suit, also in Baltimore, selecting Andrew Jackson, the ultimate victor, in May 1832.

“King Caucus” was dead. The political convention had been born. And the country never looked back.

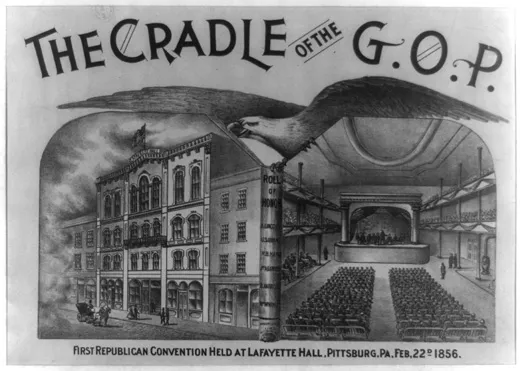

2. 1856 Republican Convention—The first national convention of the Republican Party marks the beginning of the two-party system as we know it. Meeting in Philadelphia, the new party chose John C. Frémont –the “Pathfinder” who mapped the way West for a generation of pioneers. A popular hero, Frémont also provided the new party with its slogan: “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free men, Frémont.” The slavery issue had become America’s undeniable fault line, even if most Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln, sought only to end the extension of slavery, not abolish it outright..

Frémont also ignited the first “birther” controversy. Opponents claimed he was born in Canada–and worse, back then, he was Catholic! (Former president Fillmore, onetime Anti-Mason, was nominated that year by the Know-Nothings, another odd third party which opposed immigration and foreigners.)

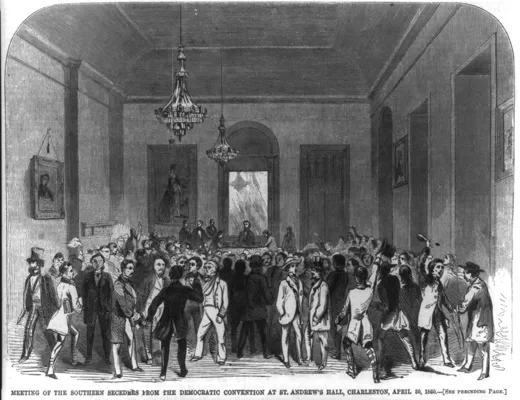

3. 1860 and its Four Conventions—This was the year of not one but four of the most important conventions, producing four candidates—two of them Democrats. In April, the Democrats met in Charleston, South Carolina, but produced no candidate, the first and only time to-date a convention has come up empty. Slavery split the party as southern delegates walked out.

In June, northern Democrats met in Baltimore and chose Stephen Douglas, the powerful Illinois Senator who had famously debated Abraham Lincoln in the 1858 Illinois Senate race. The disaffected southern Democrats also met in Baltimore and chose Kentucky’s John C. Breckenridge and demanding federal protection of slavery.

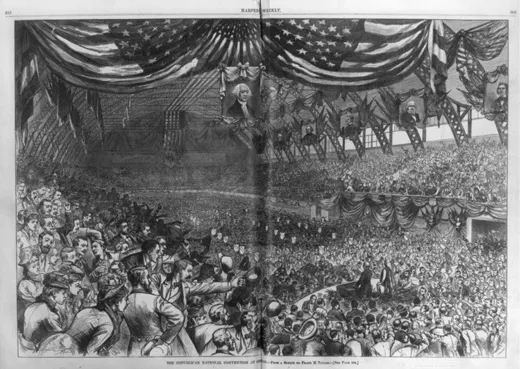

In the meantime, the Republicans met in the Wigwam, a huge building in Chicago, and on the third ballot, chose one-term Illinois Representative Abraham Lincoln. Another splinter group, the Constitutional Union Party, chose former Speaker of the House John Bell.

As all four candidates campaigned, the 1860 election went to Lincoln with about 40 percent of the vote. And the headlong race toward secession and Civil War quickly followed.

4. 1880 Republican Convention—The post-Civil War period produced lively conventions but few fireworks as Republicans dominated presidential politics for a generation. But the GOP meeting in Chicago in 1880 was stuck between two battling wings of the party: the “Stalwarts” who wanted to maintain the “boss system” in which powerful congressmen made the decisions; and the “Half-Breeds” who sought civil service reform among other changes. After 35 ballots, Civil War veteran, Ohio congressman James A. Garfield, was a surprise “dark horse” compromise, with the vice presidential nod going to Chester A. Arthur as a concession to the Stalwarts. A New York lawyer, Arthur had built his career on patronage jobs. Then an assassin’s bullet made Arthur, the “gentleman boss,” the president.

5. 1900 Republican Convention—With the death of Garret Hobart, William McKinley’s first vice president, in November 1899, the GOP was looking for a replacement for the upcoming election. (At the time, there was no Constitutional mechanism for replacing a vice president who died or succeeded to the presidency, a problem resolved in 1967 by the 25th Amendment.) “Under no circumstances could I or would I accept the nomination for the vice-president,” the young governor of New York announced in February 1900. But in June, Theodore Roosevelt changed his tune.

Powerful New York bosses wanted this reform-minded governor out of the way and pushed him onto the McKinley ticket at the Philadelphia convention where frenzied delegates rallied to the Rough Riding hero of San Juan Hill. “Don’t any of you realize,” warned McKinley advisor Senator Mark Hanna, “that there is only one life between that madman and the Presidency.”

In September 1901, McKinley was assassinated. Theodore Roosevelt became America’s youngest president.

6. 1912 Republican Convention—After Theodore Roosevelt completed his own full term in 1908, he contemplated another run but opted to uphold the two-term precedent. He turned the reins over to William Howard Taft, whose last name was said to stand for, “Take Advice From Theodore.”

But following a four-year hiatus, Roosevelt wanted to return to the White House and challenged his successor, winning several primaries but not a majority of delegates. The party regulars remained steadfast to the incumbent Taft and Roosevelt bolted the Chicago convention, claiming he had been robbed, and formed a third party, the Progressive, or “Bull Moose Party,” soon thereafter. The most successful third party candidate ever, Roosevelt finished second; he and Taft had split the Republican vote, leaving an opening for Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency.

7. 1932 Democratic Convention—No surprise here. As the Great Depression worsened, Democrats were confident that the GOP’s 12-year hold on the White House would end with Herbert Hoover’s defeat. But who would get the nod? New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt and former Governor Al Smith, who lost to Hoover in 1928, were rivals. On the fourth ballot, FDR was anointed, aided by Speaker of the House, Texas’ John Nance Garner who became his vice president.

FDR signaled a new era in American politics when he became the first candidate to address the convention, held in Chicago. In his acceptance speech, he promised America a “New Deal.”

In 1940, Eleanor Roosevelt became the first First Lady to address a convention in Chicago –also notable for giving FDR his third consecutive nomination and an unprecedented third term.

8. 1960 Democratic Convention—There was nothing new about television at the Democratic convention in Los Angeles. The first televised convention had been Philadelphia’s Republican gathering in 1940—but a lot more people had television sets 20 years later. And what they saw was America’s first great made for-television candidate, John F. Kennedy, deliver an acceptance speech promising a “New Frontier” echoing FDR’s “New Deal.” And the presidential game would never be the same. A few months later, the first televised debates against Republican Richard Nixon cemented TV’s place in the American political landscape.

9. 1968 Democratic Convention—Television also played a huge role when the Democrats met in Chicago. But it was mostly about what was happening outside the hall. The nation watched the spectacle of anti-war protestors in full battle with Chicago policemen. One Democratic Senator told the convention there were, “Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago.” The convention selected Hubert Humphrey, who lost a close race to Richard Nixon. But the violent debacle in Chicago led to the first wave of primary reforms that chipped away at the power of the convention.

This convention also marked the last time that Chicago, which had hosted more conventions than any other city, would welcome a convention until the Democrats returned in 1996 to nominate Bill Clinton for a second term.

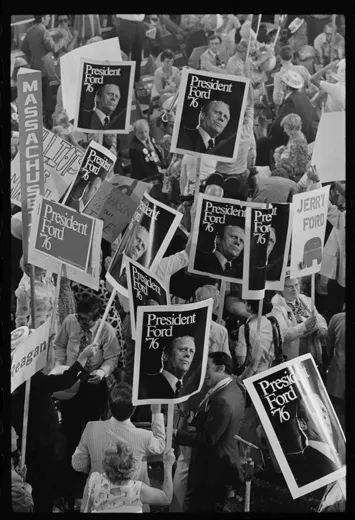

10. 1976 Republican Convention—This may have been the last hurrah for the national convention as a meaningful political battlefield. The incumbent President, Gerald Ford had succeeded to the office after Richard Nixon’s resignation. The only president never elected president or vice president, Ford faced a furious challenge from the right from former California Governor Ronald Reagan. Ford held onto the nomination in Kansas City, but lost the election to Jimmy Carter. And Ronald Reagan was probably thinking, “You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Editor's note: This story originally mistakenly referred to Garfield's assassin, Charles Guiteau, as an anarchist. This was not the case and we regret the error.