Shortly after Martha Washington became the inaugural first lady of the United States, she described her life in a letter to her niece as “more like a state prisoner than anything else.” Though Washington eventually adjusted to her status as a presidential spouse, her initial reaction to the unofficial position proved prescient for generations of first ladies. From Louisa Adams to Melania Trump, numerous first ladies have proven reluctant to take on the role.

“When people are going to criticize everything from the causes you support to the china that you pick to the clothing that you wear, how do you navigate that?” asks Lisa Kathleen Graddy, curator of the first ladies collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. “You have all of the public aspects of the job. But it’s not an office you ran for. And it doesn’t come with political aspects, but you’re treated as if it did.”

“The First Lady,” a new Showtime series created by Aaron Cooley, dramatizes the challenges faced by three first wives: Eleanor Roosevelt (portrayed by Gillian Anderson), Betty Ford (Michelle Pfeiffer) and Michelle Obama (Viola Davis). The ten-episode first season follows the women from their youth to their courtships with their future husbands to the campaign trail and beyond. Despite their many differences, executive producer Cathy Schulman tells Variety that the trio shared a key conviction: “[N]one of them wanted to be there.”

“Eleanor wanted to be there, but only if she could be president. She didn’t want to be there as first lady,” Schulman says. “And Betty went into the White House kicking and screaming. And Michelle was absolutely terrified for the lives of herself and her family.”

The showrunner adds, “[F]inding that living in that house turned out to be a benefit to themselves, to their families, to their country, ultimately, was a really interesting unifier.”

Each episode features moments in the three women’s lives and explores how they thematically intersect. Here’s what you need to know about the true history behind “The First Lady”—and the office it explores—ahead of its premiere on Sunday, April 17.

What does it mean to be first lady?

The first lady is a role “that does not exist in the Constitution, [nor] in any written-down way,” says Graddy. “There is no job description for the first lady,” and the titleholder receives no salary. Initially envisioned as a hostess, with first ladies welcoming visitors to the White House and presiding over social events, the position has “evolved over time to [become] … an adviser to the president,” says Katherine Jellison, a scholar of first ladies at Ohio University. Oftentimes, first ladies take on a public project or cause: Jackie Kennedy, for instance, championed historic preservation, while Claudia “Lady Bird” Johnson established a center dedicated to wildflowers and native plants.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/81/a1/81a11f0c-fc30-4bd4-afc2-f7f796b02194/first_ladies_at_ronald_reagan_presidential_library.jpeg)

Like their predecessors and successors, each of the three women featured in the series reshaped the public’s perception of what the first lady could be. While Eleanor connected with Americans through radio and a daily newspaper column, Betty embraced the medium of broadcast television to offer her unfiltered thoughts on relatable, contemporary problems. Michelle capitalized on the rising ubiquity of social media, using Twitter, Instagram and Facebook to reach tens of millions directly.

“The fact that [the role] is amorphous allows the first lady to create the job and … modify it as they go along,” says Graddy. “She creates it out of her own personal interests, out of the needs of the presidential administration, and [out of] the expectations of the American public both for women in general and first ladies in particular.”

Eleanor Roosevelt

In the trailer for “The First Lady,” Eleanor offers a playful rebuke to her husband, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (played by Kiefer Sutherland), reminding him that “you are the husband of a wife who has a mind and a life of her own.” The line serves as an insightful summary of Eleanor’s priorities both in and outside of the White House.

“I knew what traditionally would lie before me” as first lady, Eleanor later recalled, “and I cannot say I was very pleased with the prospect. The turmoil in my heart and mind was rather great” the night of Franklin’s election in 1932.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bc/de/bcde169f-2cd1-4d05-a0dd-70735d719349/franklin_d_roosevelt_and_eleanor_roosevelt_in_washington_washington_dc_-_nara_-_195979.jpg)

Potential conflicts of interest led Eleanor to surrender her assorted careers upon arriving at the White House, including teaching at a finishing school for girls in New York, overseeing a small factory at Val-Kill Industries and advocating for social reform. “She’s desperate to find something to do,” says Graddy. “So she finds a way to go out and gather information on what’s happening to people.” Between 1933 and 1937, she traveled an average of 40,000 miles per year, traversing the nation as her husband’s “eyes and ears.”

Eleanor “could use the excuse of ‘I’m just serving as [his] surrogate here’ and get away with doing some nontraditional kinds of activities for a first lady,” according to Jellison. Establishing herself as a beloved public figure, the first lady used her newfound platform to advocate for civil rights, women’s rights and a litany of other causes.

“She took what she initially saw as a deficit” of being first lady—the lack of privacy—and transformed it into a strength, using her high profile to bring issues “to a much larger audience than would have been the case otherwise,” says Jellison. After her 12 years in the White House, she continued this work, serving as chair of the United Nations’ Human Rights Commission and President John F. Kennedy’s Commission on the Status of Women.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/76/0f/760f4d12-325f-4347-851f-8f627db0beb2/frank.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/97/1597dbd3-807d-41d5-92a5-4f6bd6298ba0/wedding.jpg)

Born in New York in 1884, Eleanor was a member of the wealthy Roosevelt family. (Her great uncle was Theodore Roosevelt.) Orphaned at a young age, she spent her late teenage years at a boarding school in England, where her progressive views quickly took shape. She married Franklin, her fifth cousin once removed, in 1905, when she was 20 and he was 22. Over the next decade or so, the couple had six children, five of whom survived to adulthood.

As World War I drew to a close in 1918, the Roosevelts confronted the fallout of a crisis closer to home: Franklin’s affair with Eleanor’s social secretary, Lucy Mercer. After discovering letters exchanged by the lovers, Eleanor contemplated divorce, only agreeing to reconcile with her husband in order to save his political career and avoid the ire of his mother. The betrayal forever altered the couple’s relationship, transforming it into what their son James later described as “an armed truce that endured until the day [Franklin] died.”

In 1921, the couple faced yet another challenge. Then just 39, Franklin contracted polio, a disease that more typically affected children. The infection left him paralyzed from the waist down and, in an era when disability was viewed as a personal failing, threatened to end his burgeoning political career. But with the support of his family, he underwent physical therapy and mounted a successful return to politics, serving as governor of New York before his election to the presidency.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c7/c3/c7c35b63-ee94-4804-9b6c-6f9323ea4618/2560px-eleanor_roosevelt_and_lorena_hickok_-_nara_-_195609.jpeg)

On the campaign trail, Eleanor grew close to Lorena Hickok, a reporter who was assigned to cover her for the Associated Press. The women became such good friends that Hickok—realizing she could no longer objectively write about Eleanor—left journalism, took a job with the Roosevelt administration and moved into a private room adjoining the first lady’s at the White House. The pair exchanged more than 3,000 letters over some 30 years, offering intimate details of their likely romantic relationship. As Eleanor wrote to Hickok on March 11, 1933, “Oh! how I wanted to put my arms around you in reality instead of in spirit. I went & kissed your photograph instead & the tears were in my eyes.”

In “The First Lady,” Hickok (played by Lily Rabe) acts as a source of support for Eleanor, reminding her of the power of her platform. “You have an audience, your audience, your [newspaper] columns and the most powerful man in the country,” she tells Eleanor. “Use it.”

The real Hickok similarly inspired Eleanor, encouraging her to publish a syndicated daily newspaper column. Titled “My Day,” the column ran from 1935 to a few months before Eleanor’s death in November 1962, only skipping four days in April 1945, when Franklin died unexpectedly. The daily musings offer a rare glimpse into the inner workings of the White House and, in the words of Allida M. Black, director and editor of the Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project, are “the most important source on [Eleanor], period.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d4/84/d484f553-a9cf-40ab-9f00-69ec93b8dd46/ellie.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b2/07/b2079712-774c-4bb7-a9a8-451a0dcc657f/eleanor_roosevelt_-_nara_-_196187.jpeg)

Eleanor’s “My Day” entry for February 27, 1939, alludes to one of the crowning moments of her 12 years as first lady: her resignation from the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). “I belong to an organization in which I can do no active work,” she wrote. “They have taken an action which has been widely talked of in the press. To remain as a member implies approval of that action, and therefore I am resigning.”

The DAR was a historically all-white heritage group that had refused to allow Black opera singer Marian Anderson to perform at Constitution Hall, then the largest auditorium in Washington. Eleanor not only resigned from the DAR in protest but also helped organize Anderson’s history-making performance on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial later that year.

The public concert “was seen as an incredible slap in the face of Jim Crow,” says Jellison. “[Eleanor] takes the platform of being the first lady in directions that it hadn’t been taken before, and that allowed her to do so much more than if she had just been Mrs. Roosevelt.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/11/3611592d-7022-4e65-a77e-1a8a2a82f565/2560px-eleanor_roosevelt_and_marian_anderson_in_japan_-_nara_-_195989.jpeg)

Betty Ford

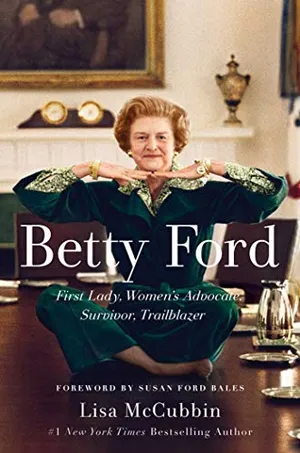

Betty and Gerald Ford (portrayed in “The First Lady” by Aaron Eckhart) never expected to end up in the White House. But fate, in the form of Vice President Spiro Agnew’s October 1973 resignation, intervened just as Gerald—then in his 25th year in Congress—was preparing to retire. “Basically their whole married life, he’d been a congressman and was traveling all the time,” says Lisa McCubbin, author of Betty Ford: First Lady, Women's Advocate, Survivor, Trailblazer. “And [Betty] said, ‘You know, I’m ready to have my husband back.”

Betty Ford: First Lady, Women's Advocate, Survivor, Trailblazer

From Lisa McCubbin, the inspiring story of an ordinary Midwestern girl thrust onto the world stage and into the White House under extraordinary circumstances

Far from stepping out of the spotlight, Gerald found himself elevated to the nation’s second-highest office in December 1973. (Advisers told President Richard Nixon that Gerald, then the popular House minority leader, was the Republican most likely to be easily confirmed by Congress.) His tenure as vice president was brief, lasting less than a year. As the threat of Nixon’s impeachment grew stronger, the president’s chief of staff, Al Haig, advised Gerald to prepare himself for yet another unexpected promotion. On August 8, 1974, the day after Nixon’s resignation, Gerald was sworn in as the U.S.’ 38th commander-in-chief, becoming the first person to hold the title without being elected as either president or vice president.

Betty was less than enthused by this turn of events. “Within a span of nine months, she went from being a relatively unknown congressman's wife to being first lady,” says McCubbin. “It was like whiplash, completely unexpected and something that she had never sought or wanted.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e4/64/e464ee4f-7b89-452a-bf6d-c31e660d3e7b/bloomer.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a8/6c/a86ce08e-5e2c-4f20-a998-989d0c8ae81c/1280px-gerald_r_ford_with_mrs_ford_and_michael_ford_-_nara_-_7064467.jpg)

Then a 56-year-old mother of four, Betty had a somewhat atypical background for a first lady. A former dancer (she’d trained under Martha Graham) and divorcée (she split from her first husband in 1947), she arrived at the White House ready to “do the best I can” while remaining true to herself. As she later recalled, “[I]f they don’t like it, they can kick me out, but they can’t make me somebody I’m not.”

A few weeks into her time as first lady, Betty held a press conference that set the tone for the next two and a half years. She expressed her support for the Equal Rights Amendment and less restrictive abortion laws, traded barbs with reporters, and refused to shy away from difficult questions. As her husband worked to restore the public’s trust in the office of the president, Betty brought “a new sense of candor and immediacy to the role of the first lady,” says Jellison. In interviews with the press, she discussed topics that women across the country were debating—abortion, marijuana, women’s rights, sex—in a way that no first lady ever had before.

“I feel very strongly that it was the best thing in the world when the Supreme Court voted to legalize abortion and ... bring it out of the backwoods,” Betty told “60 Minutes” in 1975. A few minutes later, the first lady breezed through a question about her daughter’s sex life, saying she “wouldn’t be surprised” if Susan, “a perfectly normal human being like all young girls,” was “having an affair,” as moderator Morley Safer put it. From there, the interview moved on to marijuana, with Betty declaring that she “probably would have” tried the drug if it had been available in her youth.

Public backlash to the segment was immediate, with critics decrying Betty’s comments as tasteless and obscene. In the long run, however, the interview helped boost her approval rating, cementing her status as a truly modern, outspoken first lady.

Shortly after Betty held her first press conference in September 1974, she faced arguably the defining moment of her time in the White House. After a routine checkup uncovered a malignant lump in her right breast, she underwent a radical mastectomy—and, true to form, kept the public updated on every step of the health scare. Defying the taboo surrounding breast cancer at the time, she encouraged other women to conduct self-breast exams and schedule mammograms, raising awareness of the disease and kickstarting efforts to improve early detection rates.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2f/b3/2fb3a25f-a1e0-4ab3-975e-cfe320cff691/1024px-president_richard_nixon_pat_nixon_vice_president_gerald_ford_and_betty_ford_walking_from_the_white_house_to_the_presidents_helicopter.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0b/93/0b93ea2b-8299-4a80-97f1-455e21dda93b/1024px-first_lady_betty_ford_dancing_on_the_cabinet_room_table_-_nara_-_45644161.jpeg)

“She realized that being first lady carries this weight,” says McCubbin. “It was a platform like no other, a megaphone that she could use for good.”

Betty was similarly transparent about her post-White House health struggles. Settling back into civilian life after Gerald’s loss to Jimmy Carter in the 1976 presidential election, she developed an addiction to alcohol and pills, which she’d been taking for years to treat her arthritis and mental health. Frightened by her rapid downward spiral, the Fords staged an intervention in April 1978. Betty agreed to enter an intensive, four-week inpatient treatment, and later that month, revealed her addiction to the public in a characteristically candid statement. In 1982, she and a friend founded the Betty Ford Center, an addiction treatment facility in southern California that catered largely to women.

“[Betty] herself wished she’d never had any acquaintance with breast cancer and substance abuse,” says Jellison. “But she didn’t hide these challenges in her life from the American public. Instead, she embraced them and brought a new awareness that saved the lives of countless other women.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/a4/8da48028-d59c-4462-8fab-be558c0d6dd0/first_lady_betty_ford_and_comedian_marty_allen_dancing_in_the_grand_hall_following_a_state_dinner_honoring_the_president_and_first_lady_of_liberia_-_nara_-_12007069.jpeg)

Michelle Obama

As the first Black woman to hold the title of first lady, Michelle faced an added layer of pressure upon arriving at the White House in January 2009. She had to be likable and accessible to the public in the way that all first ladies do, says Graddy, while simultaneously navigating overt and veiled racism. “If there was a presumed grace assigned to my white predecessors, I knew it was not likely to be the same for me,” Michelle wrote in her 2018 memoir, Becoming. “... My grace would need to be earned.”

The first lady also had to contend with the fact that she was “a descendant of the very caste of people that some of the previous first ladies had owned,” noted journalist Isabel Wilkerson for the New York Times in 2018. The paternal great-great granddaughter of Jim Robinson, who was born enslaved in South Carolina around 1850, she acknowledged the irony of “wak[ing] up every morning in a house that was built by slaves, … watch[ing] my daughters, two beautiful, intelligent, Black young women, playing with their dogs on the White House lawn.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d5/8b/d58b8e92-2e10-4b63-9f18-1974a34cdd4d/barack_michelle.jpeg)

The daughter of a homemaker and a city water plant employee whose struggles with multiple sclerosis loomed over her childhood, Michelle and her brother, Craig, grew up in a one-bedroom apartment on the South Side of Chicago. Her parents “poured their energy into their children, who they hoped would fulfill the families’ as yet unrealized aspirations,” according to Wilkerson. “We were their investment, me and Craig,” wrote Michelle in Becoming. “Everything went into us.”

After graduating from high school in 1981 as the salutatorian of her class, Michelle followed in her brother’s footsteps by attending Princeton University. She then earned a law degree from Harvard and started working at a law firm in Chicago, where, in 1989, she was assigned to mentor an associate named Barack (played by O-T Fagbenle in “The First Lady”). Unimpressed by his “poorly lit head shot of a guy with a big smile and a whiff of geekiness,” Michelle was also reluctant to date someone she was advising. But Barack eventually won her over, and the couple wed in October 1992. Michelle gave birth to their daughters, Malia and Sasha, in 1998 and 2001, respectively.

As Barack pursued a career in politics, serving first in the Illinois Senate and then the U.S. Senate, Michelle established herself as a leading figure in Chicago’s public sector. Though Barack never explicitly asked Michelle to give up her career, she chose to join him on the presidential campaign trail and eventually took a leave of absence from her job at the University of Chicago Hospitals.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/58/5f/585f60cd-a5a4-49e3-a723-1d94fd6b8146/barack_obama_family_portrait_2011.jpeg)

“The way I look at it is we’re running for president of the United States. Me, Barack, Sasha, Malia, my mom, my brother, his sisters—we’re all running,” Michelle told Vanity Fair in 2007. “If I really felt it was more important for me to be vice president of community and external affairs full-time, I would do that. But the bigger goal here is to get a good president—somebody I believe in, like Barack, who’s really going to be focused on the needs of ordinary people.”

Once in the White House, Michelle strived to keep preserve at least a modicum of privacy for her daughters as they came of age. In her more public-facing role as first lady, she championed such causes as expanding post-high school education opportunities, educating girls around the world and ending childhood obesity.

“Michelle Obama always approached the topic of health care from the perspective of a mom, of a family, of someone who cares about the generation of kids that are going to come after the Obama administration,” political scientist Lauren Wright told NBC News in 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/54/36543e06-f95e-4aef-9994-3d766281e1ad/michelle_obama_at_snhu_october_2016.jpeg)

Beyond her core areas of advocacy, Michelle earned the public’s admiration with her eloquent speeches, savvy use of social media and grace under pressure—attributes she has continued to embrace in her post-White House life. “When they go low, we go high,” she famously said at the 2016 Democratic National Convention.

“Her power is a symbolic power,” Nell Irvin Painter, a historian at Princeton, told the Washington Post in 2016. “... She has grace, there is no question, but I would add elegance. It’s a kind of assurance that is also something new for a Black woman in public life. She is the symbol of what an American can be. Michelle Obama has presented a universal American identity.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/98/28/9828ba28-be38-42e9-96ce-4515434f3ad5/first_lady3.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)