Two aspiring knights stood side by side, one welcoming his first son and heir, the other acting as his godfather—“virtually a family member,” according to historian Eric Jager.

Just over a decade later, however, the two men, Jean de Carrouges and Jacques Le Gris, met on a field in Paris for a highly publicized duel to the death. Jager chronicled how the former friends’ relationship devolved—and the woman and rape allegation at the center of the conflict—in the 2004 nonfiction book The Last Duel. Now, the story of the 1386 trial by combat is the subject of a blockbuster film of the same name. Directed by Ridley Scott, the movie stars Matt Damon as Carrouges, Adam Driver as Le Gris and Jodie Comer as Carrouges’ second wife, Marguerite. Ben Affleck co-wrote the script with Damon and Nicole Holofcener and appears as a feudal lord and compatriot of both leading men.

On December 29, 1386, before a crowd presided over by French king Charles VI, Carrouges and Le Gris eyed each other warily. Marguerite, who had accused Le Gris of raping her, watched from the sidelines; clad entirely in black, she was keenly aware that her husband’s defeat would be viewed as proof of perjury, vindicating her attacker and ensuring her execution by burning at the stake for the crime of bearing false witness.

“Lady, on your evidence I am about to hazard my life in combat with Jacques Le Gris,” Carrouges said to Marguerite in the moments leading up to the duel. “You know whether my cause is just and true.” She replied, “My Lord, it is so, and you can fight with confidence, for the cause is just.” And so Le Gris’ trial by combat began.

From the mechanics of trial by combat to the prosecution of sexual violence in medieval society, here’s what you need to know about the true history behind The Last Duel ahead of the film’s October 15 debut. (Spoilers ahead.)

Who’s who in The Last Duel?

A bit of a crash course on medieval France: At the top of society was the king, advised by his high council, the Parlement of Paris. Beneath him were three main ranks of nobility: barons, knights and squires. Barons like Affleck’s character, Count Pierre d’Alencon, owned land and often acted as feudal lords, providing property and protection to vassals—the term for any man sworn to serve another—in exchange for their service. Knights were one step above squires, but men of both ranks often served as vassals to higher-ranking overlords. (Le Gris and Carrouges both started out as squires and vassals to Count Pierre, but Carrouges was knighted for his military service in 1385.) At the bottom of the social ladder were warriors, priests and laborers, who had limited rights and political influence.

Is The Last Duel based on a true story?

In short, yes. The first two chapters of the three-act film, penned by Damon and Affleck, draw heavily on Jager’s research, recounting Marguerite’s rape and the events surrounding it from the perspectives of Carrouges and Le Gris, respectively. (Jager offered feedback on the film’s script, suggesting historically accurate phrasing and other changes.) The third and final section, written by Holofcener, is told from Marguerite’s point of view. As Damon tells the New York Times, this segment “is kind of an original screenplay … because that world of women had to be almost invented and imagined out of whole cloth.”

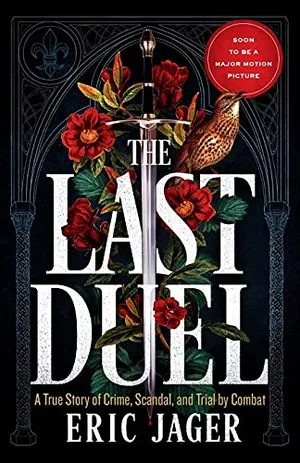

The Last Duel: A True Story of Crime, Scandal, and Trial by Combat

The gripping true story of the duel to end all duels in medieval France as a resolute knight defends his wife’s honor against the man she accuses of a heinous crime

The film adaptation traces the trio’s relationship from its auspicious beginnings to its bloody end. After Marguerite’s rape, Carrouges petitions the French court to try Le Gris through judicial combat. (Writing for History News Network, Jager explains that “the ferocious logic of the duel implied that proof was already latent in the bodies of the two combatants, and that the duel’s divinely assured outcome would reveal which man had sworn falsely and which had told the truth.”) Marguerite, as chief witness in the case, will be executed if her husband loses the duel, thereby “proving” both of their guilt.

Much like Jager’s book, the film doesn’t offer a sympathetic portrayal of either of its leading men. Carrouges views himself as a chivalrous knight defending his wife’s honor, while Le Gris casts himself as the Lancelot to Marguerite’s Guinevere, rescuing her from an unhappy marriage. Only in the final section of the film, when Marguerite is allowed to speak for herself, does the truth of the men’s personalities emerge: Carrouges—a “jealous and contentious man,” in Jager’s words—is mainly concerned with saving his own pride. Le Gris, “a large and powerful man” with a reputation as a womanizer, is too self-centered to acknowledge the unwanted nature of his advances and too self-assured to believe that, once the deed is done, Marguerite will follow through on her threat of seeking justice.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a0/3d/a03d3c49-f5f5-42c2-8e15-fe9df3514061/v7kopkduazwz5vkraoelylrcmu.jpeg)

“The penalty for bearing false witness is that you are to be burned alive,” an official tells Marguerite in the movie’s trailer. “I will not be silent,” she responds, teary-eyed but defiant.

The film’s shifting viewpoints underscore the thorny nature of truth in Marguerite’s case, which divided observers both at the time and in the centuries since. Some argued that she’d falsely accused Le Gris, either mistaking him for someone else or acting on the orders of her vindictive husband. Enlightenment thinkers Diderot and Voltaire favored Le Gris’ cause, decrying his “barbaric and unjust trial by combat” as an example of “the supposed ignorance and cruelty of the Middle Ages,” writes Jager. Later encyclopedia entries echoed this view, seemingly solidifying the question of Le Gris’ innocence.

Jager, for his part, tells Medievalists.net that he “never would have embarked on writing this book if I had not believed Marguerite.” Le Gris’ lawyer, Jean Le Coq, arguably summarized the case best, noting in his journal that “no one really knew the truth of the matter.”

What events does The Last Duel dramatize?

Born into a noble Norman family around the 1330s, Carrouges met Le Gris, a lower-born man who rose through the ranks by virtue of his own political savvy, while both were serving as vassals of Count Pierre. The pair enjoyed a close friendship that soured when the count showered lavish gifts of land and money on Le Gris, fomenting Carrouges’ jealousy. An intensely personal rivalry, exacerbated by a series of failed legal cases brought by Carrouges, emerged between the onetime friends.

In 1384, Carrouges and Marguerite encountered Le Gris at a mutual friend’s party. Seemingly resolving their differences, the men greeted each other and embraced, with Carrouges telling Marguerite to kiss Le Gris “as a sign of renewed peace and friendship,” according to Jager. The event marked the first meeting between Carrouges’ wife—described by a contemporary chronicler as “beautiful, good, sensible and modest”—and Le Gris. (At this point, the two men were in their late 50s, which places Damon at close to the right age for his role but Driver a good generation off the mark.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bb/f9/bbf91868-c79b-4433-9dcc-dfa2bfda1633/screen_shot_2021-10-13_at_93924_pm_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/39/65/39656d82-1b61-48ef-8a47-a4013f0ecbe0/screen_shot_2021-10-13_at_93303_pm_1.png)

Whether Carrouges and Le Gris actually ended their quarrel at this point is debatable. But Marguerite certainly made an impression on Le Gris, who likely still held a grudge against his litigious former friend: After running into the newly knighted Carrouges in January 1386, Le Gris sent a fellow courtier, Adam Louvel, to keep an eye on Marguerite, who’d been left behind with her mother-in-law while Carrouges traveled to Paris. As Jager explains, “With a motive, revenge against the knight, and a means, the seduction of his wife, all [Le Gris] needed now was an opportunity.”

No one really knew the truth of the matter.

Le Gris’ window arrived on January 18, when Marguerite happened to be left alone with just one maidservant. According to testimony later provided by Carrouges and Marguerite, she heard a knock on the door and opened it to find Louvel. Recognizing the courtier, who claimed to have come to ask a favor and warm himself by the fire, she allowed him to enter the house, at which point he turned the conversation to Le Gris, saying, “The squire loves you passionately, he will do anything for you, and he greatly desires to speak to you.” Alarmed by the sudden shift in tone, Marguerite attempted to rebuke Louvel, only to turn around and see Le Gris, who’d snuck in through the unlocked door.

Le Gris quickly turned violent, forcing her upstairs and enlisting Louvel to help restrain her as she desperately fought back. After the sexual assault, Le Gris told Marguerite, “Lady, if you tell anyone what has happened here, you will be dishonored. If your husband hears of it, he may kill you. Say nothing, and I will keep quiet, too.” In response, Marguerite said, “I will keep quiet. But not for as long as you need me to.” Tossing a sack of coins at the young woman, Le Gris taunted her, claiming that his friends would give him an airtight alibi.

“I don’t want your money!” Marguerite replied. “I want justice! I will have justice!”

How did victims of sexual violence seek justice in medieval society?

When Carrouges returned home three or four days after Marguerite’s rape, he found his wife “sad and tearful, always unhappy in expression and demeanor, and not at all her usual self.” She waited until the two were alone before revealing what had happened and urging her husband to seek vengeance against Le Gris. Barred from bringing a case against Le Gris herself, Marguerite had to rely entirely on her husband to mount legal action.

The majority of medieval rape victims lacked the means to seek justice. Per historian Kathryn Gravdal, a register of crimes recorded in four French hamlets between 1314 and 1399 lists just 12 rape or attempted rape cases, as “only virgins or high-status rape victims”—like Marguerite—“actually had their day in court.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/85/78/8578e8e8-272c-4186-8b69-bf58280769d1/g_thelastduel_4_21551_9481ed30.jpeg)

Those who did report their rapes found the odds “really stacked against them,” with the onus on the survivor to “make a big judicial issue of it as quickly as possible,” says historian Hannah Skoda, author of the 2012 book Medieval Violence. She adds, “If there’s any gap between the act and … making people aware [of it], that raises huge questions.”

Medieval law treated rape as a horrific crime on par with other capital offenses. But conceptions of rape varied widely, with some commentators arguing that women enjoyed being taken by force and others accusing survivors of falsely accusing men in order to trick them into marriage. (Rapists sometimes escaped punishment by marrying their victims.) The dominant belief that women had to enjoy sex in order to conceive further complicated matters, leaving those impregnated by their rapists on even shakier legal ground. Marguerite, who found herself pregnant soon after the attack, largely left this fact out of her account, either due to uncertainty over the child’s paternity—he may have been conceived before Carrouges left for Paris—or an awareness that making this claim would weaken her testimony in the eyes of the court. She gave birth to a son, Robert, shortly before Le Gris’ trial by combat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/76/51/7651aed0-d174-4401-8262-5cb0080411b5/christine_de_pisan_-_cathedra.jpeg)

Because rape was viewed less as an act of sexual violence than a property crime against the victim’s husband or guardian, rapists often avoided harsh penalties by paying a fine to the man in question. The burden of proof lay almost entirely on victims, who had to prove they’d resisted the rapist’s advances while recounting their testimony in precise detail. Even a small mistake, such as misstating the day the attack happened, could result in the case being thrown out and the victim being punished for perjury.

“Marguerite tells her story, and she knows … that she needs to be extremely consistent, despite this absolutely horrific trauma that she’s just gone through,” says Skoda. “She has to relive it over and over again—and she gets it right.”

Initially, Carrouges brought Marguerite’s case to Count Pierre. Given the count’s strong relationship with Le Gris and combative past with Carrouges, he was quick to dismiss the claim, even arguing that Marguerite “must have dreamed it.” Undeterred, Carrouges raised an appeal with the king.

The fate that awaited Marguerite if her husband’s attempts failed—being burned at the stake for bearing false witness—represented an extreme example of the potential repercussions faced by accusers. “If the case is not proven, then [the woman] doesn’t just get to walk away,” says Skoda. “She’s going to face some kind of penalty.” Instead of being executed, however, most women on the losing side of rape cases endured “custodial or financial [punishment], which in medieval terms is kind of the end of everything anyway,” according to Skoda.

Despite the threat of public humiliation and potentially deadly outcome of disclosing one’s rape, women like Marguerite spoke out, perhaps as a way of working through their trauma or simply refusing to “passively accept [what had] happened to them,” says Skoda. Pointing out that women’s voices are actually “loud and clear,” albeit filtered through the court system and notaries, in many medieval documents, the historian explains, “It’s a really nice way of sort of flipping our stereotypes of the Middle Ages. ... It was a patriarchal and deeply misogynist [time]. But that doesn’t mean that women were silenced. They still spoke out, and they still fought against the grain.”

How did Marguerite’s case lead to a trial by combat?

French law stipulated that noblemen appealing their cause to the king could challenge the accused to a judicial duel, or trial by combat. Known as the “judgment of God,” these ordeals were thought to have a divinely ordained outcome, with the loser proving his guilt by the very act of defeat. Cases had to meet four requirements, including exhausting all other legal remedies and confirming that the crime had actually occurred.

Legal historian Ariella Elema, whose PhD research centered on trial by combat in France and England, says judicial duels were most common in “cases where the evidence was really unclear and it was difficult to solve the [matter] by any other means.” Such clashes had become increasingly rare by the late 14th century, with lawyers largely using the prospect of duels to incentivize individuals to settle cases out of court. Of the judicial duels that actually took place, few ended in death. Instead, Elema explains, authorities overseeing trials typically imposed a settlement after the fighters had exchanged a few blows.

For Carrouges and Le Gris, whose dispute had sparked widespread interest across France, settling the case would have been viewed as “either an admission of guilt or [a] false accusation,” says Elema. “There [wasn’t] going to be a settlement without one of them losing their reputation.”

After hearing both parties’ testimony, the Parlement of Paris agreed to authorize a duel—France’s first trial by combat for a rape case in more than 30 years. According to Jager, the court “may have feared taking sides and arousing even more controversy, deciding instead to grant the knight’s request, authorize a duel and leave the whole perplexing matter in the hands of God.”

Five contemporary or near-contemporary chronicles offer accounts of what happened when Le Gris and Carrouges met on December 29, 1386. Jean Froissart, writing after the duel, describes Marguerite praying as she watched the fight, adding, “I do not know, for I never spoke with her, whether she had not often regretted having gone so far with the matter that she and her husband were in such grave danger.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/63/20/63203198-95b3-445a-9c9c-794fd46930f4/gerichtskampf_mair.jpeg)

Elema’s interpretation of the sources differs from Jager’s comparatively colorful recounting. As she argues, “Instead of a duel that was long and drawn out and involved many different weapons and a whole variety of exciting scenarios, it seems to have been a very short affair that shocked the audience.”

Two likely eyewitnesses—the author of the Chronicle of the Monk of Saint-Denis and Le Coq—agree that Le Gris landed the first blow, piercing Carrouges’ thigh with his sword. In Le Coq’s words, his client “attacked his adversary very cruelly and did it on foot, although he would have had the advantage if he had done it on horseback.” By drawing blood, writes Elema for the Historical European Martial Arts and Sports Community, Le Gris prevented the king from halting the duel, as “once the scales had tipped in one fighter’s favor, no one could stop the fight without the appearance of partiality.”

A seasoned warrior with more fighting experience than Le Gris, Carrouges quickly rebounded from his injury, gaining the upper hand and pushing his opponent to the ground. Unable to rise due to the weight of his body armor, Le Gris resisted Carrouges’ calls to confess, declaring, “In the name of God, and on the peril and damnation of my soul, I am innocent of the crime.” Enraged, Carrouges delivered the death blow, perhaps by stabbing Le Gris’ exposed neck or thighs. Le Gris’ final moments appear to have been grisly even by the standards of the day: The monk of Saint-Denis, who served as Charles VI’s official historian, reported that Carrouges “killed his enemy with great difficulty because he was encased in armor.” In accordance with tradition, authorities dragged Le Gris’ body to the gallows and hung him as a final insult to his sullied reputation.

What happened after the duel?

Though Scott’s film and its source text afford the fight the weighty title of the last duel, Le Gris’ trial by combat was far from the last duel to ever take place. Rather, it was the last judicial duel sanctioned by the Parlement of Paris—a decision possibly motivated by the decidedly unchivalrous nature of the event. Duels of honor, as well as judicial duels authorized by other governing bodies, continued to take place centuries after Carrouges’ triumph.

The knight’s victory saved both him and his wife, earning the formerly notorious couple wealth and prestige. Carrouges died roughly a decade after the duel, falling in combat against the Ottoman Turks. Marguerite’s fate is unknown, though later historians convinced of the falsity of her claims suggested she retired to a convent out of shame.

Far from echoing these Enlightenment-era assessments of Marguerite’s misguided intentions, the film adaptation of The Last Duel presents the noblewoman as its protagonist, the “truth teller [whose account is] so much more resonant, strong and evident” than her male counterparts’, as Affleck tells GMA News.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/12/93/129331a5-34f2-40f2-9f81-9aad73e74019/nicopol_final_battle_1398.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ba/20/ba20fc74-4a95-483c-b88c-abcd2ea1827f/madness.jpg)

The actor continues, “It’s an anti-chivalry movie in some sense because the great illusion of chivalry is that it was about … [protecting] the innocent female. And in fact it was a code, a manner of behavior that denied women’s basic humanity.”

Skoda and Elema argue that Marguerite’s case exemplifies the complexity of medieval society, which is often painted in broad, reductive strokes.

“People tend to think of the Middle Ages being less sophisticated than they actually are, but there’s this this huge, fascinating legal tradition that’s the origin of pretty much all of Western legal tradition,” Elema says.

Skoda adds, “It’s all too tempting to talk about the Middle Ages as this horrible, misogynist, patriarchal, oppressive society, as a way of even implicitly just saying, ‘Look how far we’ve come.’ … Whereas to complicate what things looked like in the 14th century complicates what we’re doing now.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(600x337:601x338)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/09/9a/099aff12-775d-4d4b-bf11-ccea60f4e1de/13239beb-0e3e-4942-869d-b215e913e3ca_w1200_r177_fpx34_fpy39.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)