The True Story of the Battle of Bunker Hill

Nathaniel Philbrick takes on one of the Revolutionary War’s most famous and least understood battles

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Patriot-Games-Bunker-Hill-631.jpg)

The last stop on Boston’s Freedom Trail is a shrine to the fog of war.

“Breed’s Hill,” a plaque reads. “Site of the Battle of Bunker Hill.” Another plaque bears the famous order given American troops as the British charged up not-Bunker Hill. “Don’t fire ’til you see the whites of their eyes.” Except, park rangers will quickly tell you, these words weren’t spoken here. The patriotic obelisk atop the hill also confuses visitors. Most don’t realize it’s the rare American monument to an American defeat.

In short, the nation’s memory of Bunker Hill is mostly bunk. Which makes the 1775 battle a natural topic for Nathaniel Philbrick, an author drawn to iconic and misunderstood episodes in American history. He took on the Pilgrim landing in Mayflower and the Little Bighorn in The Last Stand. In his new book, Bunker Hill, he revisits the beginnings of the American Revolution, a subject freighted with more myth, pride and politics than any other in our national narrative.

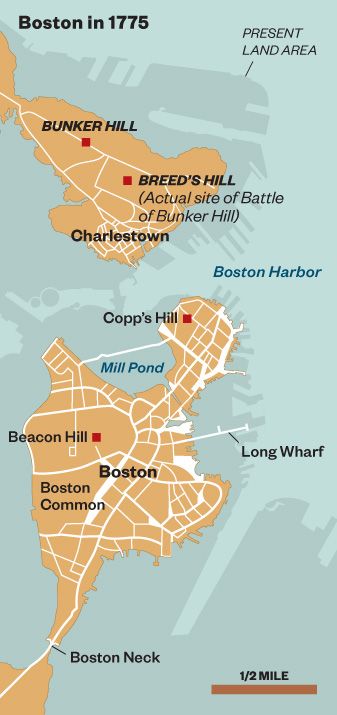

“Johnny Tremain, Paul Revere’s Ride, today’s Tea Partiers—you have to tune all that out to get at the real story,” Philbrick says. Gazing out from the Bunker Hill Monument—not at charging redcoats but at skyscrapers and clotted traffic—he adds: “You also have to squint a lot and study old maps to imagine your way back into the 18th century.”

***

Boston in 1775 was much smaller, hillier and more watery than it appears today. The Back Bay was still a bay and the South End was likewise underwater; hills were later leveled to fill in almost 1,000 acres. Boston was virtually an island, reachable by land only via a narrow neck. And though founded by Puritans, the city wasn’t puritanical. One rise near Beacon Hill, known for its prostitutes, was marked on maps as “Mount Whoredom.”

Nor was Boston a “cradle of liberty”; one in five families, including those of leading patriots, owned slaves. And the city’s inhabitants were viciously divided. At Copp’s Hill, in Boston’s North End, Philbrick visits the grave of Daniel Malcom, an early agitator against the British identified on his headstone as “a true son of Liberty.” British troops used the patriot headstone for target practice. Yet Malcom’s brother, John, was a noted loyalist, so hated by rebels that they tarred and feathered him and paraded him in a cart until his skin peeled off in “steaks.”

Philbrick is a mild-mannered 56-year-old with gentle brown eyes, graying hair and a placid golden retriever in the back of his car. But he’s blunt and impassioned about the brutishness of the 1770s and the need to challenge patriotic stereotypes. “There’s an ugly civil war side to revolutionary Boston that we don’t often talk about,” he says, “and a lot of thuggish, vigilante behavior by groups like the Sons of Liberty.” He doesn’t romanticize the Minutemen of Lexington and Concord, either. The “freedoms” they fought for, he notes, weren’t intended to extend to slaves, Indians, women or Catholics. Their cause was also “profoundly conservative.” Most sought a return to the Crown’s “salutary neglect” of colonists prior to the 1760s, before Britain began imposing taxes and responding to American resistance with coercion and troops. “They wanted the liberties of British subjects, not American independence,” Philbrick says.

That began to change once blood was shed, which is why the Bunker Hill battle is pivotal. The chaotic skirmishing at Lexington and Concord in April 1775 left the British holed up in Boston and hostile colonists occupying the city’s surrounds. But it remained unclear whether the ill-equipped rebels were willing or able to engage the British Army in pitched battle. Leaders on both sides also thought the conflict might yet be settled without full-scale war.

This tense, two-month stalemate broke on the night of June 16, in a confused manner that marks much of the Revolution’s start. Over a thousand colonials marched east from Cambridge with orders to fortify Bunker Hill, a 110-foot rise on the Charlestown peninsula jutting into Boston Harbor. But the Americans bypassed Bunker Hill in the dark and instead began fortifying Breed’s Hill, a smaller rise much closer to Boston and almost in the face of the British.

The reasons for this maneuver are murky. But Philbrick believes it was a “purposeful act, a provocation and not the smartest move militarily.” Short on cannons, and the know-how to fire those they had with accuracy, the rebels couldn’t do much damage from Breed’s Hill. But their threatening position, on high ground just across the water from Boston, forced the British to try to dislodge the Americans before they were reinforced or fully entrenched.

On the morning of June 17, as the rebels frantically threw up breastworks of earth, fence posts and stone, the British bombarded the hill. One cannonball decapitated a man as his comrades worked on, “fatigued by our Labour, having no sleep the night before, very little to eat, no drink but rum,” a private wrote. “The danger we were in made us think there was treachery, and that we were brought there to be all slain.”

Exhausted and exposed, the Americans were also a motley collection of militia from different colonies, with little coordination and no clear chain of command. By contrast, the British, who at midday began disembarking from boats near the American position, were among the best-trained troops in Europe. And they were led by seasoned commanders, one of whom marched confidently at the head of his men accompanied by a servant carrying a bottle of wine. The British also torched Charlestown, at the base of Breed’s Hill, turning church steeples into “great pyramids of fire” and adding ferocious heat to what was already a warm June afternoon.

All this was clearly visible to the many spectators crowded on hills, rooftops and steeples in and around Boston, including Abigail Adams and her young son, John Quincy, who cried at the flames and the “thunders” of British cannons. Another observer was British Gen. John Burgoyne, who watched from Copp’s Hill. “And now ensued one of the greatest scenes of war that can be conceived,” he wrote of the blazing town, the roaring cannons and the sight of red-coated troops ascending Breed’s Hill.

However, the seemingly open pasture proved to be an obstacle course. The high, unmown hay obscured rocks, holes and other hazards. Fences and stone walls also slowed the British. The Americans, meanwhile, were ordered to hold their fire until the attackers closed to 50 yards or less. The wave of British “advanced towards us in order to swallow us up,” wrote Pvt. Peter Brown, “but they found a Choaky mouthful of us.”

When the rebels opened fire, the close-packed British fell in clumps. In some spots, the British lines became jumbled, making them even easier targets. The Americans added to the chaos by aiming at officers, distinguished by their fine uniforms. The attackers, repulsed at every point, were forced to withdraw. “The dead lay as thick as sheep in a fold,” wrote an American officer.

The disciplined British quickly re-formed their ranks and advanced again, with much the same result. One British officer was moved to quote Falstaff: “They make us here but food for gunpowder.” But the American powder was running very low. And the British, having failed twice, devised a new plan. They repositioned their artillery and raked the rebel defenses with grapeshot. And when the infantrymen marched forward, a third time, they came in well-spaced columns rather than a broad line.

As the Americans’ ammunition expired, their firing sputtered and “went out like an old candle,” wrote William Prescott, who commanded the hilltop redoubt. His men resorted to throwing rocks, then swung their muskets at the bayonet-wielding British pouring over the rampart. “Nothing could be more shocking than the carnage that followed the storming [of] this work,” wrote a royal marine. “We tumbled over the dead to get at the living,” with “soldiers stabbing some and dashing out the brains of others.” The surviving defenders fled, bringing the battle to an end.

In just two hours of fighting, 1,054 British soldiers—almost half of all those engaged—had been killed or wounded, including many officers. American losses totaled over 400. The first true battle of the Revolutionary War was to prove the bloodiest of the entire conflict. Though the British had achieved their aim in capturing the hill, it was a truly Pyrrhic victory. “The success is too dearly bought,” wrote Gen. William Howe, who lost every member of his staff (as well as the bottle of wine his servant carried into battle).

Badly depleted, the besieged British abandoned plans to seize another high point near the city and ultimately evacuated Boston. The battle also demonstrated American resolve and dispelled hopes that the rebels might relent without a protracted conflict. “Our three generals,” a British officer wrote of his commanders in Boston, had “expected rather to punish a mob than fight with troops that would look them in the face.”

The intimate ferocity of this face-to-face combat is even more striking today, in an era of drones, tanks and long-range missiles. At the Bunker Hill Museum, Philbrick studies a diorama of the battle alongside Patrick Jennings, a park ranger who served as an infantryman and combat historian for the U.S. Army in Iraq and Afghanistan. “This was almost a pool-table battlefield,” Jennings observes of the miniature soldiers crowded on a verdant field. “The British were boxed in by the terrain and the Americans didn’t have much maneuverability, either. It’s a close-range brawl.”

However, there’s no evidence that Col. Israel Putnam told his men to hold their fire until they saw “the whites” of the enemies’ eyes. The writer Parson Weems invented this incident decades later, along with other fictions such as George Washington chopping down a cherry tree. In reality, the Americans opened fire at about 50 yards, much too distant to see anyone’s eyes. One colonel did tell his men to wait until they could see the splash guards—called half-gaiters—that British soldiers wore around their calves. But as Philbrick notes, “‘Don’t fire until you see the whites of their half-gaiters’ just doesn’t have the same ring.” So the Weems version endured, making it into textbooks and even into the video game Assassin’s Creed.

The Bunker Hill Monument also has an odd history. The cornerstone was laid in 1825, with Daniel Webster addressing a crowd of 100,000. Backers built one of the first railways in the nation to tote eight-ton granite blocks from a quarry south of Boston. But money ran out. So Sarah Josepha Hale, a magazine editor and author of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” rescued the project by organizing a “Ladies’ Fair” that raised $30,000. The monument was finally dedicated in 1843, with the now-aged Daniel Webster returning to speak again.

Over time, Brahmin Charlestown turned Irish and working class, and the monument featured in gritty crime movies like The Town, directed by Ben Affleck (who has also acquired the movie rights to Philbrick’s book). But today the obelisk stands amid renovated townhouses, and the small park surrounding it is popular with exercise classes and leisure-seekers. “You’ll be talking to visitors about the horrible battle that took place here,” says park ranger Merrill Kohlhofer, “and all around you are sunbathers and Frisbee players and people walking their dogs.” Firemen also visit, to train for climbing tall buildings by scaling the 221-foot monument.

Philbrick is drawn to a different feature of the park: a statue of what he calls the “wild man” and neglected hero of revolutionary Boston, Dr. Joseph Warren. The physician led the rebel underground and became major general of the colonial army in the lead-up to Bunker Hill. A flamboyant man, he addressed 5,000 Bostonians clad in a toga and went into the Bunker Hill battle wearing a silk-fringed waistcoat and silver buttons, “like Lord Falkland, in his wedding suit.” But he refused to assume command, fighting as an ordinary soldier and dying from a bullet in the face during the final assault. Warren’s stripped body was later identified on the basis of his false teeth, which had been crafted by Paul Revere. He left behind a fiancée (one of his patients) and a mistress he’d recently impregnated.

“Warren was young, charismatic, a risk-taker—a man made for revolution,” Philbrick says. “Things were changing by the day and he embraced that.” In death, Warren became the Revolution’s first martyr, though he’s little remembered by most Americans today.

***

Before leaving Charlestown, Philbrick seeks out one other site. In 1775, when Americans marched past Bunker Hill and fortified Breed’s instead, a British map compounded the confusion by mixing up the two hills as well. Over time, the name Breed’s melted away and the battle became indelibly linked to Bunker. But what of the hill that originally bore that name?

It’s visible from the Bunker Hill Monument: a taller, steeper hill 600 yards away. But Charlestown’s narrow, one-way streets keep carrying Philbrick in the wrong direction. After 15 minutes of circling his destination he finally finds a way up. “It’s a pity the Americans didn’t fortify this hill,” he quips, “the British would never have found it.”

It’s now crowned by a church, on Bunker Hill Street, and a sign says the church was established in 1859, “On the Top of Bunker Hill.” The church’s business manager, Joan Rae, says the same. “This is Bunker Hill. That other hill’s not. It’s Breed’s.” To locals like Rae, perhaps, but not to visitors or even to Google Maps. Tap in “Bunker Hill Charlestown” and you’ll be directed to...that other hill. To Philbrick, this enduring confusion is emblematic of the Bunker Hill story. “The whole thing’s a screw-up,” he says. “The Americans fortify the wrong hill, this forces a fight no one planned, the battle itself is an ugly and confused mess. And it ends with a British victory that’s also a defeat.”

Retreating to Boston for lunch at “ye olde” Union Oyster House, Philbrick reflects more personally on his historic exploration of the city where he was born. Though he was mostly raised in Pittsburgh, his forebears were among the first English settlers of the Boston area in the 1630s. One Philbrick served in the Revolution. As a championship sailor, Philbrick competed on the Charles River in college and later moved to Boston. He still has an apartment there, but mostly lives on the echt-Yankee island of Nantucket, the setting for his book about whaling, In the Heart of the Sea.

Philbrick, however, considers himself a “deracinated WASP” and doesn’t believe genealogy or flag-waving should cloud our view of history. “I don’t subscribe to the idea that the founders or anyone else were somehow better than us and that we have to live up to their example.” He also feels the hated British troops in Boston deserve reappraisal. “They’re an occupying army, locals despise them, and they don’t want to be there,” he says. “As Americans we’ve now been in that position in Iraq and can appreciate the British dilemma in a way that wasn’t easy before.”

But Philbrick also came away from his research with a powerful sense of the Revolution’s significance. While visiting archives in England, he called on Lord Gage, a direct descendant of Gen. Thomas Gage, overall commander of the British military at the Bunker Hill battle. The Gage family’s Tudor-era estate has 300 acres of private gardens and a chateau-style manor filled with suits of armor and paintings by Gainsborough, Raphael and Van Dyck.

“We had sherry and he could not have been more courteous,” Philbrick says of Lord Gage. “But it was a reminder of the British class system and how much the Revolution changed our history. As countries, we’ve gone on different paths since his ancestor sent redcoats up that hill.”

Read an excerpt from Philbrick's Bunker Hill, detailing the tarring and feathering of loyalist John Malcom on the eve of the Revolutionary War, here.