The Ugliest, Most Contentious Presidential Election Ever

Throughout the 1876 campaign, Tilden’s opposition had called him everything from a briber to a thief to a drunken syphilitic

![]()

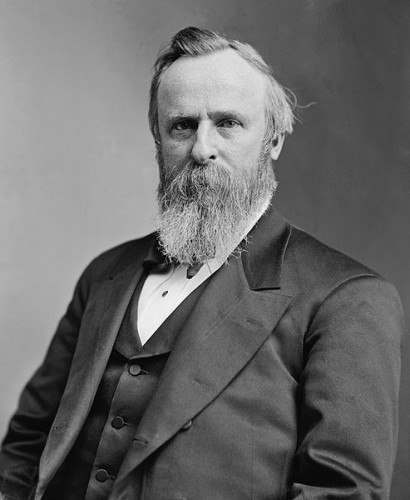

For Rutherford B. Hayes, election evening of November 7, 1876, was shaping up to be any presidential candidate’s nightmare. Even though the first returns were just coming in by telegraph, newspapers were announcing that his opponent, the Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, had won. Hayes, a Republican, would indeed lose the popular vote by more than a quarter-million, but he had no way of knowing that as he prepared his concession speech. He went to bed a gloomy man and consoled his wife, Lucy Webb. “We soon fell into a refreshing sleep,” Hayes wrote in his diary, “and the affair seemed over.”

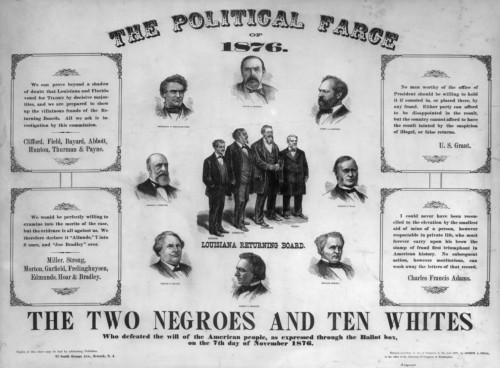

But the ugliest, most contentious and most controversial presidential election in U.S. history was far from over. Throughout the campaign, Tilden’s opposition had called him everything from a briber to a thief to a drunken syphilitic. Suspicion of voter fraud in Republican-controlled states was rampant, and heavily armed and marauding white supremacist Democrats had canvassed the South, preventing countless blacks from voting. As a result, Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina were deemed too close to call, and with those states still in question, Tilden remained one electoral vote short of the 185 required by the Constitution to win election. With 165 electoral votes tallied for Hayes, all he needed to do was capture the combined 20 electoral votes from those three contested states, and he’d win the presidency. The ensuing crisis took months to unfold, beginning with threats of another civil war and ending with an informal, behind-the-scenes deal—the Compromise of 1877—that gave Hayes the presidency in exchange for the removal of federal troops from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction.

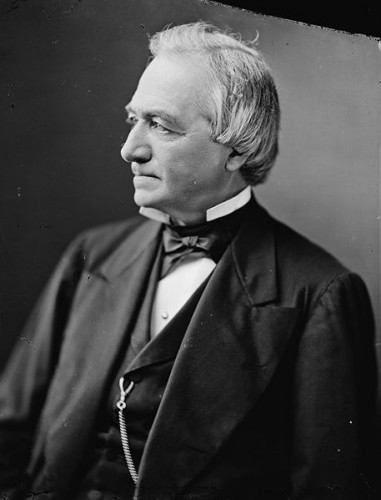

For Samuel Tilden, the evening of November 7, 1876, was cause for celebration. He was on his way toward winning an absolute majority of votes cast (he would capture 51.5 percent to Hayes’s 48 percent) and gave newfound hope to Democrats, who had been largely shut out of the political process in the years following the Civil War.

Born in 1814 in New York State, Tilden studied at Yale and New York University. After being admitted to the bar in 1841, he made himself rich as a corporate lawyer, representing railroad companies and making real estate investments. After the Civil War, he built up a relationship with William M. “Boss” Tweed, the head of Tammany Hall, the Democratic political machine that dominated New York politics in the 19th century. But when Tilden entered the New York State Assembly in 1872, he earned a reputation for stifling corruption, which put him at odds with the machine. He became governor of New York State in 1874, and gained a national reputation for his part in breaking up massive fraud in the construction and repair of the state’s canal system. His efforts gained him the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination.

Tilden was attacked on everything from his chronic ill health and his connections to the railroad industry, widely viewed as rife with corporate corruption at the time. Sixty-two and a lifelong bachelor, he was respected for his commitment to political reform though considered dull. With corruption charges plaguing associates of the sitting president, Ulysses S. Grant, Tilden’s candidacy could not have been better timed for Democrats to regain national power.

Although he captured the popular vote, the newly “reconstructed” states of Louisiana, Florida and South Carolina, still under federal occupation, hung in the balance. The Republican Party, which controlled the canvassing boards, quickly challenged the legitimacy of those states’ votes, and on a recount, supposedly supervised by personal agents who were dispatched to these states by President Grant (along with federal troops), many of Tilden’s votes began to be disqualified for unspecified “irregularities.” Democrats had no doubts Republicans were stuffing ballot boxes and claimed there were places where the number of votes exceeded the population. Most egregious was Louisiana’s alleged offer by the Republican-controlled election board: For the sum of $1,000,000, it would certify that the vote had gone to the Democrats. The Democratic National Committee rejected the offer, but similar reports of corruption, on both sides, were reported in Florida and South Carolina.

After all three contested states submitted two sets of electoral ballots (one for each candidate), Congress established an electoral commission in January of 1877, made up of five senators, five Supreme Court justices and five members of the House of Representatives. The commission—seven Republicans, seven Democrats and one Independent—heard arguments from lawyers who represented both Hayes and Tilden. Associate Justice Joseph P. Bradley of New Jersey emerged as the swing vote in the decision to name the next president of the United States.

Associate Justice Joseph P. Bradley, the swing vote on the Electoral Commission, changed his mind at the last moment. Photo: Wikipedia

On the evening before the votes were to be cast, Democrats paid a visit to Bradley, who read his opinion, indicating that Florida’s three electoral votes would be awarded to Tilden, giving him enough to win. But later that evening, after Democratic representatives had left Bradley’s home, Republican Senator Frederick T. Frelinghuysen of New Jersey and George M. Robeson, Secretary of the Navy, arrived for some last-minute lobbying. Aided by Mary Hornblower Bradley, the Justice’s wife, the two Republicans managed to convince Bradley that a Democratic presidency would be a “national disaster.” The commission’s decision made the final electoral tally 185 to 184 for Hayes.

Democrats were not done fighting, however. The Constitution required a president to be named by March 4, otherwise an interregnum occurred, which opened up numerous possibilities for maneuvering and chaos. The Democrats threatened a filibuster, which would delay the completion of the election process and put the government in uncharted waters. The threat brought Republicans to the negotiating table, and over the next two days and nights, representatives from both parties hammered out a deal. The so-called Compromise of 1877, would remove federal troops from the South, a major campaign issue for Democrats, in exchange for the dropped filibuster.

The compromise enabled Democrats to establish a “Solid South.” With the federal government leaving the region, states were free to establish Jim Crow laws, which legally disenfranchised black citizens. Frederick Douglass observed that the freedmen were quickly turned over to the “rage of our infuriated former masters.” As a result, the 1876 presidential election provided the foundation for America’s political landscape, as well as race relations, for the next 100 years.

While Hayes and the Republicans presumptively claimed rights to victory, Tilden proved to be a timid fighter and discouraged his party from challenging the commission’s decision. Instead, he spent more than a month preparing a report on the history of electoral counts—which, in the end, had no effect on the outcome.

“I can retire to public life with the consciousness that I shall receive from posterity the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people,” Tilden said after his defeat, “without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office.”

His health did indeed fail him shortly after the election. He died in 1886 a wealthy man, leaving $3 million to the New York Public Library.

Sources

Articles: ”The Election That Got Away,” by Louis W. Koenig, American Heritage, October, 1960. “Samuel J. Tilden, The Man Who Should Have Been President,” Great Lives in History, February 9, 2010, http://greatlivesinhistory.blogspot.com/2010/02/february-9-samuel-j-tilden-man-who.html ”Volusion Confusion: Tilden-Hayes,” Under the Sun, November 20, 2000, http://www.historyhouse.com/uts/tilden_hayes/

Books: Roy Morris, Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the Stolen Election of 1876, Simon & Schuster, 2003. John Bigelow and Nikki Oldaker, The Life of Samuel J. Tilden, Show Biz East Productions, 2009.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)