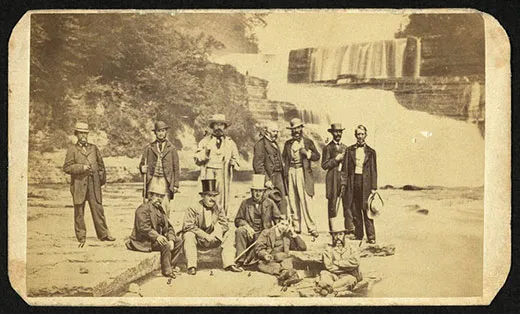

The Unknown Contributions of Brits in the American Civil War

Historian Amanda Foreman discusses how British citizens took part in the war between the Union and the Confederacy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Brits-in-the-Civil-War-631.jpg)

Though often overlooked, more than 50,000 British citizens served in various capacities in the American Civil War. Historian Amanda Foreman looked at their personal writings and tells the story of the war and Britain’s involvement in it in her latest book, A World on Fire, recently named one of the New York Times’ 100 Notable Books of 2011.

I spoke with the author—born in London, raised in Los Angeles and schooled at Sarah Lawrence College, Columbia University and Oxford University—about the role Britain, and one particular Brit, Henry Morton Stanley, played in the conflict.

Why is it that more people don’t know about international involvement in the American Civil War?

When teaching time is limited, you are just going to stick to the bare essentials. Who fought the war. What were the major battles. When did it end. What was the war about. You are not going to look at other aspects in high school. That’s the first thing.

The second thing is when you get to college and you start looking at the Civil War in a more nuanced way, generally that means race, class and gender. The international dimensions of the war cut across all three and therefore end up falling between the cracks because they don’t sit exclusively within one of those particular areas.

There are lots of legitimate reasons why people haven’t thought about international aspects of the war for a very long time. But the reason why you have to is because it turns out that those very aspects played a very important role in the war. I believe it is impossible to understand the war without also understanding those aspects.

What were the most surprising revelations you made about the war by looking at it from a world perspective?

The first thing I really understood was the limitations of foreign diplomacy in early American politics. It was very much the custom in the 19th century and especially in the mid-century for secretaries of state to consider their role a steppingstone towards the White House. In no way was it a tool for actual foreign diplomacy. When William Henry Seward, who was the secretary of state at the time, took office he just resolutely refused to accept that the pronouncements he made in the U.S. for a domestic audience were having such a crushingly disastrous effect on America’s reputation abroad. His own words served to drive Europe, and in particular Britain, from being willing allies at the beginning of the war towards the North into hostile neutrals.

By turning Britain into a hostile neutral, it meant that the South suddenly had an enormous leg up in the war. All the actions that Britain could have taken to make life difficult for the South—for example, barring any Southern ship from landing in British ports—never happened. And, in fact, the South began to genuinely believe that it had a chance of winning recognition from Britain of Southern independence, which I believe helped prolong the war by at least two years.

In what ways was Britain invested or really tied up in the war?

At the beginning of the war, cotton impacted the livelihoods of one in five Englishmen in some way. Everyone was worried that the cotton embargo would destroy Britain’s financial might. But it turned out that there was a huge cotton glut in 1860. There was too much cotton in England in warehouses, and it was bringing down the price of finished goods. So what the war did was rescue Britain from a serious industrial slump that was about to take place. For the first 18 months of the war, British merchants just used up the cotton that they had stored. Then, finally, when the cotton became scarce, truly, truly scarce midway through the war, there were other sources of cotton coming from India and Egypt. By then, Britain had become completely invested in the war because of the war economy. Guns, cannons, rifles, bullets, uniforms, steel plating of all kind, engines, everything that a war needs, Britain was able to export to the North and to the South. In fact, Britain’s economy grew during the Civil War. So just from a financial point of view, Britain was heavily invested industrially.

Second of all, Britain was heavily invested because of the bonds. Both the South and the North needed to sell bonds on the international market to raise money to fight the war. The British were the largest holder of these bonds.

Of course, what is interesting to us is not so much that, but what the British people were thinking and feeling. We know they felt a great deal because over 50,000 sailed from Britain to the U.S. to take part, to fight, to volunteer.

Can you talk about some of the capacities in which they served?

They served in all capacities. We have the famous actor-manager Charles Wyndham. If you go to London, Wyndham’s Theatre is one of the famous theaters on Drury Lane. But before he became the famous Charles Wyndham, he actually had trained to be a doctor. He wasn’t a very successful doctor. He was having difficulty keeping his patients in England as a young man. So when the war started he went out and he joined the federal army as a surgeon and accompanied Gen. [Nathaniel P.] Banks on his Red River campaign in Louisiana. He spent the first three years of the war as a surgeon until finally he went back in 1864.

The head of the Oxford Infirmary [in England] was a man called Charles Mayo. He also volunteers as a surgeon and became second in command of the medical corps in Vicksburg and was there for the fall of Vicksburg.

These are British soldiers who really played a prominent part in the military life of the war, who just resigned their positions and came over to fight. There is even an English Medal of Honor winner, Philip Baybutt. Sir John Fitzroy De Courcy, who later became Lord Kingsale, was the colonel of the 16th Ohio Volunteers. He was the colonel who captured the Cumberland Gap from the Confederacy. They all have their part to play. Then, of course, you have those on the Southern side, who are in some ways more characterful because it was harder to get to the South. They had to run the blockade. There was no bounty to lure them. They literally went there out of sheer idealism.

Henry Morton Stanley, a Welsh journalist and explorer of Africa best known for his search for Dr. Livingstone, served in the Civil War. How did he get involved?

He had come [to the United States] before the war. He was living in Arkansas, apprenticed to someone. He hadn’t actually had any intention of joining up, but he was shamed into joining when he was sent a package with women’s clothes inside of it—a southern way of giving him the white feather. So he joined the Dixie Grays. He took part in the Battle of Shiloh. He was captured and sent to Camp Douglas, one of the most notorious prison camps in the North, in Chicago. It had a terrible death rate.

He was dying, and he just decided that he wanted to live. He was a young man, and so he took the oath of loyalty and switched sides. Then he was shipped out to a northern hospital prior to being sent into the field. As he began to get better, he realized that he didn’t want to fight anymore. So he very quietly one day got dressed and walked out of the hospital and didn’t look back. That was in 1862. He went back to Wales, where he discovered his family didn’t want to know him. Then he went back to New York. He clerked for a judge for a while. He decided this wasn’t earning him enough money, so he joined the Northern navy as a ship’s writer and was present at the Battle of Wilmington at Fort Fisher, the last big naval battle in 1865. About three weeks after the Battle of Wilmington, he jumped ship with a friend.

So he didn’t really have moral reasons for allying with either side?

No, not at all. He was a young man. He just got caught up. He kept a diary, which is a little bit unreliable but pretty good. It is very eloquent. When he was captured after the Battle of Shiloh, he got into an argument with his captors. He was saying, “Well, what is the war about?” And they said, “Well, it’s about slavery.” He suddenly realized that maybe they were right. He just never thought of it. He said, “There were no blackies in Wales.”

How does Stanley’s experience of the war compare with those of other Brits who served?

Henry joined out of necessity, not out of ideology. That is different from most British volunteers who joined the Confederate army. So he was very rare in the fact that he was so willing to switch sides. Also, he is one of the very rare prisoners to survive incarceration in a federal prison or a prisoner of war camp. His description of what it was like is very valuable because it is so vivid and horrendous. He saw people drowning in their own feces. They had such bad dysentery they would fall into a puddle of human waste and drown there, too weak to pull themselves out.

In their recent book Willpower, authors Roy Baumeister and John Tierney show how willpower works through different character studies, including one of Henry Morton Stanley. Is there a time during Stanley’s service or imprisonment where you think he displays incredible willpower?

Oh, sure. This is a young man who is able to keep his eye on the prize, which is survival. Also, he wants to make something of himself. He keeps those two things at the forefront of his mind and doesn’t allow the terrible, crushing circumstances around him to destroy him.

Did you come across any techniques of his to actually get through the suffering?

Yes, his remarkable ability to lie and believe the lie as truth.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)