The Unsuccessful Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln

On the eve of his first inauguration, President Lincoln snuck into Washington at night, evading the would-be assassins who waited for him in Baltimore

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lincoln-Assasination-House-Peril-631.jpg)

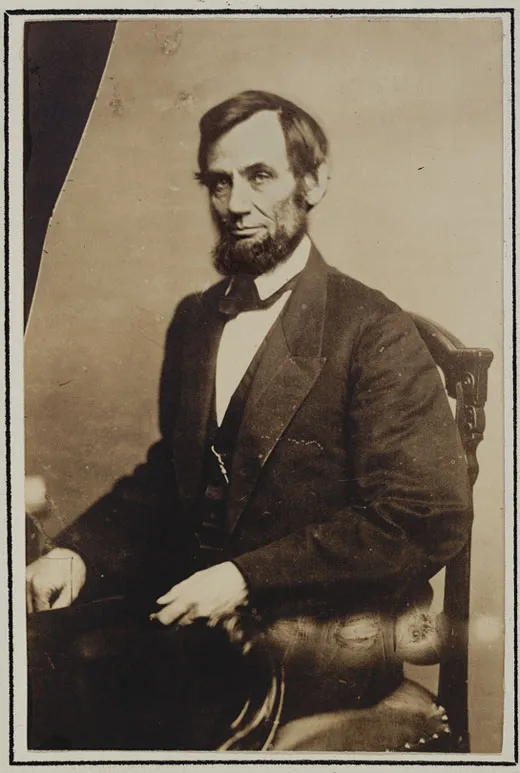

As he awaited the outcome of the voting on election night, November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln sat expectantly in the Springfield, Illinois, telegraph office. The results came in around 2 a.m.: Lincoln had won. Even as jubilation erupted around him, he calmly kept watch until the results came in from Springfield, confirming that he had carried the town he had called home for a quarter century. Only then did he return home to wake Mary Todd Lincoln, exclaiming to his wife: “Mary, Mary, we are elected!”

At the new year, 1861, he was already beleaguered by the sheer volume of correspondence reaching his desk in Springfield. On one occasion he was spotted at the post office filling “a good sized market basket” with his latest batch of letters, and then struggling to keep his footing as he navigated the icy streets. Soon, Lincoln took on an extra pair of hands to assist with the burden, hiring John Nicolay, a bookish young Bavarian immigrant, as his private secretary.

Nicolay was immediately troubled by the growing number of threats that crossed Lincoln’s desk. “His mail was infested with brutal and vulgar menace, and warnings of all sorts came to him from zealous or nervous friends,” Nicolay wrote. “But he had himself so sane a mind, and a heart so kindly, even to his enemies, that it was hard for him to believe in political hatred so deadly as to lead to murder.” It was clear, however, that not all the warnings could be brushed aside.

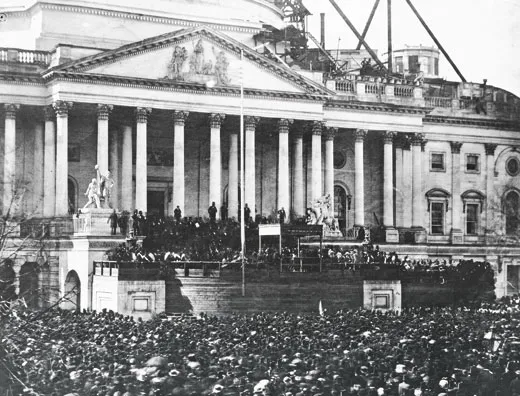

In the coming weeks, the task of planning Lincoln’s railway journey to his inauguration in the nation’s capital on March 4 would present daunting logistical and security challenges. The task would prove all the more formidable because Lincoln insisted that he utterly disliked “ostentatious display and empty pageantry,” and would make his way to Washington without a military escort.

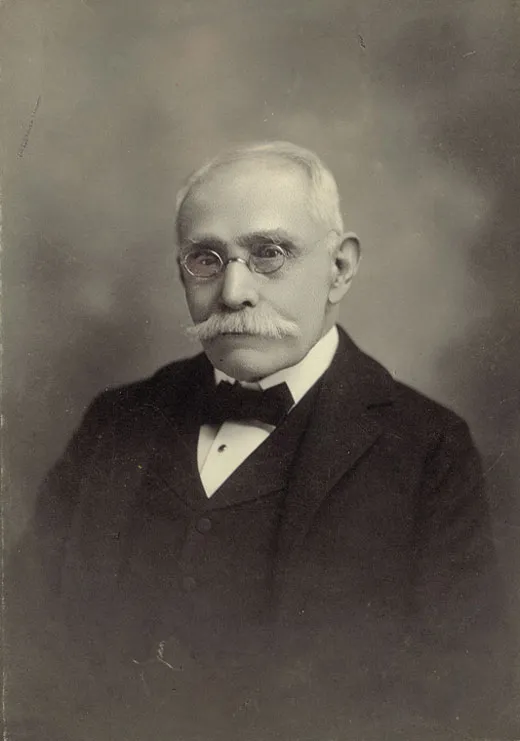

Far from Springfield, in Philadelphia, at least one railway executive—Samuel Morse Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad—believed that the president-elect had failed to grasp the seriousness of his position. Rumors had reached Felton—a stolid, bespectacled blueblood whose brother was president of Harvard at the time—that secessionists might be mounting a “deep-laid conspiracy to capture Washington, destroy all the avenues leading to it from the North, East, and West, and thus prevent the inauguration of Mr. Lincoln in the Capitol of the country.” For Felton, whose track formed a crucial link between Washington and the North, the threat against Lincoln and his government also constituted a danger to the railroad that had been his life’s great labor.

“I then determined,” Felton recalled later, “to investigate the matter in my own way.” What was needed, he realized, was an independent operative who had already proven his mettle in the service of the railroads. Snatching up his pen, Felton dashed off an urgent plea to “a celebrated detective, who resided in the west.”

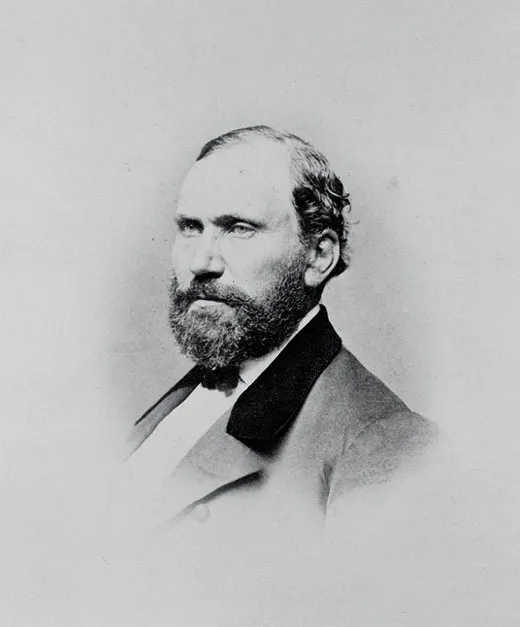

By the end of January, with barely two weeks remaining before Lincoln was to depart Springfield, Allan Pinkerton was on the case.

A Scottish immigrant, Pinkerton had started out as a cooper making barrels in a village on the Illinois prairies. He had made a name for himself when he helped his neighbors snare a ring of counterfeiters, proving himself fearless and quick-witted. He had gone on to serve as the first official detective for the city of Chicago, admired as an incorruptible lawman. By the time Felton sought him out, the ambitious 41-year-old Pinkerton presided over the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Among his clients was the Illinois Central Railroad.

Felton’s letter landed on Pinkerton’s desk in Chicago on January 19, a Saturday. The detective set off within moments, reaching Felton’s office in Philadelphia only two days later.

Now, as Pinkerton settled into a chair opposite Felton’s broad mahogany desk, the railroad president outlined his concerns. Shocked by what he was hearing, Pinkerton listened in silence. Felton’s plea for help, the detective said, “aroused me to a realization of the danger that threatened the country, and I determined to render whatever assistance was in my power.”

Much of Felton’s line was on Maryland soil. In recent days four more states—Mississippi, Florida, Alabama and Georgia—had followed the lead of South Carolina and seceded from the Union. Louisiana and Texas would soon follow. Maryland had been roiling with anti-Northern sentiment in the months leading up to Lincoln’s election, and at the very moment that Felton poured out his fears to Pinkerton, the Maryland legislature was debating whether to join the exodus. If war came, Felton’s PW&B would be a vital conduit of troops and ammunition.

Both Felton and Pinkerton appear to have been blind, at this early stage, to the possibility of violence against Lincoln. They understood that the secessionists sought to prevent the inauguration, but they had not yet grasped, as Felton would later write, that if all else failed, Lincoln’s life was to “fall a sacrifice to the attempt.”

If the plotters intended to disrupt Lincoln’s inauguration—now only six weeks away—it was evident that any attack would come soon, perhaps even within days.

The detective departed immediately for “the seat of danger”—Baltimore. Virtually any route that the president-elect chose between Springfield and Washington would pass through the city. A major port, Baltimore had a population of more than 200,000—nearly twice that of Pinkerton’s Chicago—making it the nation’s fourth-largest city, after New York, Philadelphia and Brooklyn, at the time a city in its own right.

Pinkerton brought with him a crew of top agents, among them a new recruit, Harry Davies, a fair-haired young man whose unassuming manner belied a razor-sharp mind. He had traveled widely, spoke many languages and had a gift for adapting himself to any situation. Best of all from Pinkerton’s perspective, Davies possessed “a thorough knowledge of the South, its localities, prejudices, customs and leading men, which had been derived from several years residence in New Orleans and other Southern cities.”

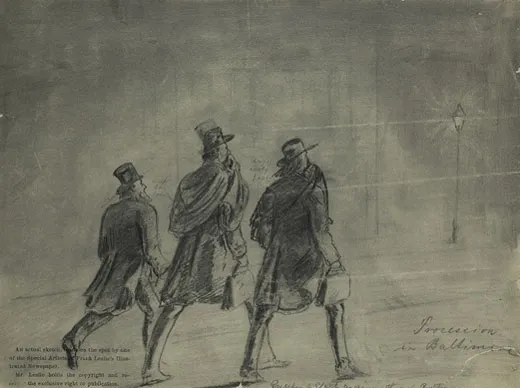

Pinkerton arrived in Baltimore during the first week of February, taking rooms at a boarding house near the Camden Street train station. He and his operatives fanned out across the city, mixing with crowds at saloons, hotels and restaurants to gather intelligence. “The opposition to Mr. Lincoln’s inauguration was most violent and bitter,” he wrote, “and a few days’ sojourn in this city convinced me that great danger was to be apprehended.”

Pinkerton decided to set up a cover identity as a newly arrived Southern stockbroker, John H. Hutchinson. It was a canny choice, as it gave him an excuse to make himself known to the city’s businessmen, whose interests in cotton and other Southern commodities often gave a fair index of their political leanings. In order to play the part convincingly, Pinkerton hired a suite of offices in a large building at 44 South Street.

Davies was to assume the character of “an extreme anti-Union man,” also new to the city from New Orleans, and put himself up at one of the best hotels, Barnum’s. And he was to make himself known as a man willing to pledge his loyalty and his pocketbook to the interests of the South.

Meanwhile, from Springfield, the president-elect offered up the first details of his itinerary. Lincoln announced that he would travel to Washington in an “open and public” fashion, with frequent stops along the way to greet the public. His route would cover 2,000 miles. He would arrive at Baltimore’s Calvert Street Station at 12:30 on the afternoon of Saturday, February 23, and depart Camden Street Station at 3. “The distance between the two stations is a little over a mile,” Pinkerton noted with concern.

Instantly, the announcement of Lincoln’s imminent arrival became the talk of Baltimore. Of all the stops on the president-elect’s itinerary, Baltimore was the only slaveholding city apart from Washington itself; there was a distinct possibility that Maryland would vote to secede by the time Lincoln’s train reached its border. “Every night as I mingled among them,” Pinkerton wrote of the circles he infiltrated, “I could hear the most outrageous sentiments enunciated. No man’s life was safe in the hands of those men.”

A timetable for Lincoln’s journey was supplied to the press. From the moment the train departed Springfield, anyone wishing to cause harm would be able to track his movements in unprecedented detail, even, at some points, down to the minute. All the while, moreover, Lincoln continued to receive daily threats of death by bullet, knife, poisoned ink—and, in one instance, spider-filled dumpling.

***

In Baltimore, meanwhile, Davies set to work cultivating the friendship of a young man named Otis K. Hillard, a hard-drinking regular of Barnum’s. Hillard, according to Pinkerton, “was one of the fast ‘bloods’ of the city.” On his chest he wore a gold badge stamped with a palmetto, the symbol of South Carolina’s secession. Hillard had recently signed on as a lieutenant in the Palmetto Guards, one of several secret military organizations springing up in Baltimore.

Pinkerton had targeted Hillard because of his association with Barnum’s. “The visitors from all portions of the South located at this house,” Pinkerton noted, “and in the evenings the corridors and parlors would be thronged by the long-haired gentlemen who represented the aristocracy of the slaveholding interests.”

Although Davies claimed to have come to Baltimore on business, at every turn, he quietly insinuated that he was far more interested in matters of “rebeldom.” Davies and Hillard soon became inseparable.

Just before 7:30 on the morning of Monday, February 11, 1861, Abraham Lincoln began knotting a hank of rope around his traveling cases. When the trunks were neatly bundled, he hastily scrawled an address: “A. Lincoln, White House, Washington, D.C.” At the stroke of 8 o’clock, the train bells sounded, signaling the hour of departure from Springfield. Lincoln turned to face the crowd from the rear platform. “My friends,” he said, “no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything...I now leave, not knowing when or whether I may return, to a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington.” Moments later, the Lincoln Special gathered steam and pushed east toward Indianapolis.

The next day, Tuesday, February 12, a significant break came for Pinkerton and Davies. In Davies’ room, he and Hillard sat talking into the early hours of the morning. “[Hillard] then asked me,” Davies reported later, “if I had seen a statement of Lincoln’s route to Washington City.” Davies lifted his head, at last catching sight of a foothold among all the slippery hearsay.

Hillard outlined his knowledge of a coded system that would allow the president-elect’s train to be tracked from stop to stop, even if telegraph communications were being monitored for suspicious activity. The codes, he continued, were only a small part of a larger design. “My friend,” Hillard said grimly, “that is what I would like to tell you, but I dare not—I wish I could—anything almost I would be willing to do for you, but to tell you that I dare not.” As the two men parted, Hillard cautioned Davies to say nothing of what had passed between them.

Meanwhile, Pinkerton, posing as the gregarious stockbroker Hutchinson, was engaged in a running debate with businessman James H. Luckett, who occupied a neighboring office.

The detective steered the conversation toward Lincoln’s impending passage through Baltimore. At the mention of Lincoln’s journey, Luckett turned suddenly cautious. “He may pass through quietly,” Luckett said, “but I doubt it.”

Seizing his opportunity, the detective pulled out his wallet and counted out $25 with a dramatic flourish. “I am but a stranger to you,” Pinkerton said, avowing his own secessionist fervor, “but that I have no doubt that money is necessary for the success of this patriotic cause.” Pressing the bills into Luckett’s hand, Pinkerton asked that the donation be used “in the best manner possible for Southern rights.” Shrewdly, Pinkerton offered a piece of advice along with his largesse, warning his new friend to be “cautious in talking with outsiders.” One never knew, Pinkerton said, when Northern agents might be listening.

The ploy worked. Luckett took the warning—along with the money—as proof of Pinkerton’s trustworthy nature. He told the detective that only a small handful of men, members of a cabal sworn to the strictest oaths of silence, knew the full extent of the plans being laid. Perhaps, Luckett said, Pinkerton might like to meet the “leading man” of the secret organization, a “true friend of the South” ready to give his life for the cause. His name was Capt. Cypriano Ferrandini.

The name was familiar to Pinkerton, as that of the barber who plied his trade in the basement of Barnum’s. An immigrant from Corsica, Ferrandini was a dark, wiry man with a chevron mustache. A day or so earlier, Hillard had brought Davies around to the barbershop, but Ferrandini had not been there to receive them.

Ferrandini was said to be an admirer of the Italian revolutionary Felice Orsini, a leader of the secret brotherhood known as the Carbonari. In Baltimore, Pinkerton believed, Ferrandini was channeling the inspiration he drew from Orsini into the Southern cause. Whether Ferrandini and a rabidly secessionist young actor known to frequent Barnum’s—John Wilkes Booth—met there remains a matter of conjecture, but it is entirely possible that the two crossed paths.

“Mr. Luckett said that he was not going home this evening,” Pinkerton reported, “and if I would meet him at Barr’s Saloon on South Street, he would introduce me to Ferrandini.”

Captain Ferrandini, he said, “had a plan fixed to prevent Lincoln from passing through Baltimore.” He would see to it that Lincoln would never reach Washington, and never become president. “Every Southern Rights man has confidence in Ferrandini,” Luckett declared. “Before Lincoln should pass through Baltimore, Ferrandini would kill him.” Smiling broadly, Luckett gave a crisp salute and left the room, leaving a stunned Pinkerton staring after him.

Pinkerton had come to Baltimore to protect Samuel Felton’s railroad. With Lincoln’s train already underway, he found himself forced to consider the possibility that Lincoln himself was the target.

Now it was clear to Pinkerton that a warning must be sent to Lincoln. Years before, during his early days in Chicago, Pinkerton had often encountered Norman Judd, the former Illinois state senator who had been instrumental in Lincoln’s election. Judd, Pinkerton knew, was now aboard the special train as a member of the president-elect’s “suite.” The detective reached for a telegraph form. Addressing his dispatch to Judd, “in company with Abraham Lincoln,” Pinkerton fired off a terse communiqué: I have a message of importance for you. Where can it reach you by special Messenger.—Allan Pinkerton

On the night of February 12, Pinkerton stepped around the corner from his office to Barr’s Saloon to keep his appointment with Luckett. Entering the bar, he called out to Luckett, who came forward to present him to Ferrandini. “Luckett introduced me as a resident of Georgia, who was an earnest worker in the cause of secession,” Pinkerton recalled, “and whose sympathy and discretion could be implicitly relied upon.” In a lowered voice, Luckett reminded Ferrandini of “Mr. Hutchinson’s” generous $25 donation.

Luckett’s endorsement had the desired effect. Ferrandini seemed to warm to the detective immediately. After ordering drinks and cigars, the group withdrew to a quiet corner. Within moments, Pinkerton noted, his new acquaintance was expressing himself in terms of high treason. “The South must rule,” Ferrandini insisted. He and his fellow Southerners had been “outraged in their rights by the election of Lincoln, and freely justified resorting to any means to prevent Lincoln from taking his seat.”

Pinkerton found that he could not dismiss Ferrandini as just another crackpot, noting the steel in his voice and easy command of the men clustered about him. The detective recognized that this potent blend of fiery rhetoric and icy resolve made Ferrandini a dangerous adversary. “He is a man well calculated for controlling and directing the ardent minded,” the detective admitted. “Even I myself felt the influence of this man’s strange power, and wrong though I knew him to be, I felt strangely unable to keep my mind balanced against him.”

“Never, never shall Lincoln be president,” Ferrandini vowed. “He must die—and die he shall.”

Despite Pinkerton’s efforts to draw him out further that night, Ferrandini did not disclose details of the plot, saying only, “Our plans are fully arranged and they cannot fail. We shall show the North that we fear them not.”

***

By Sunday, February 17, Pinkerton, after piecing together rumors and reports, had formed a working theory of Ferrandini’s plan. “A vast crowd would meet [Lincoln] at the Calvert Street depot,” Pinkerton stated. “Here it was arranged that but a small force of policemen should be stationed, and as the president arrived a disturbance would be created.” While the police rushed off to deal with this diversion, he continued, “it would be an easy task for a determined man to shoot the President, and, aided by his companions, succeed in making his escape.”

Pinkerton was convinced that Otis Hillard held the key to uncovering the final details of the plot, as well as the identity of the designated assassin. Hillard, he believed, was the weak link in Ferrandini’s chain of command.

The next evening, February 18, as Hillard and Davies dined together, Hillard confirmed that his National Volunteers unit might soon “draw lots to see who would kill Lincoln.” If the responsibility fell upon him, Hillard boasted, “I would do it willingly.”

Davies demanded to be taken to this fateful meeting, insisting that he, too, be given the “opportunity to immortalize himself” by murdering the president-elect. By February 20, Hillard returned to Davies in exuberant spirits. If he would swear an oath of loyalty, Davies could join Ferrandini’s band of “Southern patriots” that very night.

As evening fell, Hillard conducted Davies to the home of a man well known among the secessionists. The pair were ushered into a large drawing room, where 20 men stood waiting silently. Ferrandini, dressed for the occasion in funereal black from head to toe, greeted Davies with a crisp nod.

In the flickering light of candles, the “rebel spirits” formed a circle as Ferrandini instructed Davies to raise his hand and swear allegiance to the cause of Southern freedom. The initiation completed, Ferrandini reviewed the plan to divert police at the Calvert Street Station. As he brought his remarks to a “fiery crescendo,” he drew a long, curved blade from beneath his coat and brandished it high above his head. “Gentlemen,” he cried to roars of approval, “this hireling Lincoln shall never, never be President!”

When the cheers subsided, a wave of apprehension passed through the room. “Who should do the deed?” Ferrandini asked his followers. “Who should assume the task of liberating the nation of the foul presence of the abolitionist leader?”

Ferrandini explained that paper ballots had been placed into the wooden chest on the table in front of him. One ballot, he continued, was marked in red to designate the assassin. “In order that none should know who drew the fatal ballot, except he who did so, the room was rendered still darker,” Davies reported, “and everyone was pledged to secrecy as to the color of the ballot he drew.” In this manner, Ferrandini told his followers, the identity of the “honored patriot” would be protected until the last possible instant.

One by one, the “solemn guardians of the South” filed past the box and withdrew a folded ballot slip. Ferrandini himself took the final ballot and held it aloft, telling the assembly in a hushed but steely tone that their business had now come to a close.

Hillard and Davies walked out into the darkened streets together, after first withdrawing to a private corner to open their folded ballots. Davies’ own ballot paper was blank, a fact he conveyed to Hillard with an expression of ill-concealed disappointment. As they set off in search of a stiffening drink, Davies told Hillard that he worried that the man who had been chosen to carry it out—whoever he might be—would lose his nerve at the crucial moment. Ferrandini had anticipated this possibility, Hillard said, and had confided to him that a safeguard was in place. The wooden box, Hillard explained, had contained not one, but eight red ballots. Each man would believe that he alone was charged with the task of murdering Lincoln, and that the cause of the South rested solely upon “his courage, strength and devotion.” In this way, even if one or two of the chosen assassins should fail to act, at least one of the others would be certain to strike the fatal blow.

Moments later, Davies burst into Pinkerton’s office, launching into his account of the evening’s events. Pinkerton sat at his desk furiously scribbling notes as Davies spoke.

It was now clear that Pinkerton’s period of surveillance—or “unceasing shadow,” as he called it—had come to an end.

“My time for action,” he declared, “had now arrived.”

***

By the morning of February 21, Lincoln was departing New York City for the first leg of that day’s travel to Philadelphia.

Pinkerton had already traveled to Philadelphia by this time, where he was putting the finishing touches on a “plan of operation” he had devised in Baltimore. It had been only three weeks since he had met with Felton in the Quaker City.

Pinkerton believed that if he could spirit the president-elect through Baltimore ahead of schedule, the assassins would be caught off guard. By the time they took their places for the February 23 arrival in Baltimore, Lincoln would already be safe in Washington.

Pinkerton knew that what he was proposing would be risky and perhaps even foolhardy. Even if Lincoln departed ahead of schedule, the route to the capital would pass through Baltimore in any case. If any hint of a change of plan leaked out, Lincoln’s position would become far more precarious. Instead of traveling openly with his full complement of friends and protectors, he would be relatively alone and exposed, with only one or two men at his side. That being the case, Pinkerton knew that secrecy was even more critical than ever.

Shortly after 9 a.m., Pinkerton met Felton and walked with him toward the depot of the PW&B Railroad. He told Felton that his investigation left no room for doubt: “There would be an attempt made to assassinate Mr. Lincoln.” Moreover, Pinkerton concluded, if the plot were successful, Felton’s railroad would be destroyed to prevent retaliation by the arrival of Northern troops. Felton assured Pinkerton that all the resources of the PW&B would be placed at Lincoln’s disposal.

Pinkerton hurried back to his hotel, the St. Louis, and told one of his top operatives, Kate Warne, to stand by for further instructions. In 1856, Warne, a young widow, had stunned Pinkerton when she appeared at his Chicago headquarters, asking to be hired as a detective. Pinkerton at first refused to consider exposing a woman to danger in the field, but Warne persuaded him that she would be invaluable as an undercover agent. She soon demonstrated extraordinary courage, helping to apprehend criminals—from murderers to train robbers.

Pinkerton, before going out to continue making arrangements, also dispatched a trusted young courier to take a message to his old friend, Norman Judd, traveling with Lincoln.

As Lincoln arrived in Philadelphia and made his way to the luxurious Continental hotel, Pinkerton returned to his room at the St. Louis and lit a fire. Felton arrived shortly afterward, Judd at 6:45.

If Lincoln abided by his current itinerary, Pinkerton told Judd, he would be reasonably safe while still on board the special. But from the moment he landed at the Baltimore depot, and especially while riding in the open carriage through the streets, he would be in mortal peril. “I do not believe,” he told Judd, “it is possible he or his personal friends could pass through Baltimore in that style alive.”

“My advice,” Pinkerton continued, “is that Mr. Lincoln shall proceed to Washington this evening by the eleven o’clock train.” Judd made to object, but Pinkerton held up a hand for silence. He explained that if Lincoln altered his schedule in this manner, he would be able to slip through Baltimore unnoticed, before the assassins made their final preparations. “This could be done in safety,” Pinkerton said. In fact, it was the only way.

Judd’s face darkened. “I fear very much that Mr. Lincoln will not accede to this,” he said. “Mr. Judd said that Mr. Lincoln’s confidence in the people was unbounded,” Pinkerton recalled, “and that he did not fear any violent outbreak; that he hoped by his management and conciliatory measures to bring the secessionists back to their allegiance.”

In Judd’s view, the best chance of getting Lincoln to change his mind rested with Pinkerton himself. There is nothing in Pinkerton’s reports to suggest that he expected to take his concerns directly to Lincoln, nor is it likely, given his long-established passion for secrecy, that he welcomed the prospect. He had made a career of operating in the shadows, always taking care to disguise his identity and methods.

It was now nearly 9 in the evening. If they were going to get Lincoln on a train that night, they had barely two hours in which to act.

Finally, at 10:15, Pinkerton, by now waiting at the Continental, got word that Lincoln had retired for the evening. Judd dashed off a note asking the president-elect to come to his room: “so soon as convenient on private business of importance.” At last, Lincoln himself ducked through the doorway. Lincoln “at once recollected me,” Pinkerton said, from the days when both men had given service to the Illinois Central Railroad, Lincoln as a lawyer representing the railroad and Pinkerton as a detective overseeing security. The president-elect had a kind word of greeting for his old acquaintance. “Lincoln liked Pinkerton,” Judd observed, and “had the utmost confidence in him as a gentleman—and a man of sagacity.”

Pinkerton carefully reviewed “the circumstances connected with Ferrandini, Hillard and others,” who were “ready and willing to die to rid their country of a tyrant, as they considered Lincoln to be.” He told Lincoln in blunt terms that if he kept to the published schedule, “an assault of some kind would be made upon his person with a view to taking his life.”

“During the entire interview, he had not evinced the slightest evidence of agitation or fear,” Pinkerton said of Lincoln. “Calm and self-possessed, his only sentiments appeared to be those of profound regret, that the Southern sympathizers could be so far led away by the excitement of the hour, as to consider his death a necessity for the furtherance of their cause.”

Lincoln rose from his chair. “I cannot go tonight,” he said firmly. “I have promised to raise the flag over Independence Hall tomorrow morning, and to visit the legislature at Harrisburg in the afternoon—beyond that I have no engagements. Any plan that may be adopted that will enable me to fulfill these promises I will accede to, and you can inform me what is concluded upon tomorrow.” With these words, Lincoln turned and left the room.

The detective saw no alternative but to accede to Lincoln’s wishes, and immediately set to work on a new plan. Struggling to anticipate “all the contingencies that could be imagined,” Pinkerton would work through the entire night.

Just after 8 a.m., Pinkerton met again with Judd at the Continental. The detective remained secretive about the details of his plan, but it was understood that the broad strokes would remain the same: Lincoln would pass through Baltimore ahead of schedule.

The Lincoln Special pulled away from the West Philadelphia depot at 9:30 that morning, bound for Harrisburg. The detective himself stayed behind in Philadelphia to complete his arrangements. As the train neared Harrisburg, Judd told Lincoln that the matter was “so important that I felt that it should be communicated to the other gentlemen of the party.” Lincoln concurred. “I reckon they will laugh at us, Judd,” he said, “but you had better get them together.” Pinkerton would have been horrified at this development, but Judd was resolved to notify Lincoln’s inner circle before they sat down to dinner.

Arriving in Harrisburg at 1:30 p.m., and making his way to the Jones House hotel with his host, Gov. Andrew Curtin, Lincoln also decided to bring Curtin into his confidence. He told the governor that “a conspiracy had been discovered to assassinate him in Baltimore on his way through that city the next day.” Curtin, a Republican who had forged a close alliance with Lincoln during the presidential campaign, pledged his full cooperation. He reported that Lincoln “seemed pained and surprised that a design to take his life existed.” Nevertheless, he remained “very calm, and neither in his conversation or manner exhibited alarm or fear.”

At 5 that evening, Lincoln dined at the Jones House with Curtin and several other prominent Pennsylvanians. At about 5:45, Judd stepped into the room and tapped the president-elect on the shoulder. Lincoln now rose and excused himself, pleading fatigue for the benefit of any onlookers. Taking Governor Curtin by the arm, Lincoln strolled from the room.

Upstairs, Lincoln gathered a few articles of clothing. “In New York some friend had given me a new beaver hat in a box, and in it had placed a soft wool hat,” he later commented. “I had never worn one of the latter in my life. I had this box in my room. Having informed a very few friends of the secret of my new movements, and the cause, I put on an old overcoat that I had with me, and putting the soft hat in my pocket, I walked out of the house at a back door, bareheaded, without exciting any special curiosity. Then I put on the soft hat and joined my friends without being recognized by strangers, for I was not the same man.”

A “vast throng” had gathered at the front of the Jones House, perhaps hoping to hear one of Lincoln’s balcony speeches. Governor Curtin, anxious to quiet any rumors if Lincoln were spotted leaving the hotel, called out orders to a carriage driver that the president-elect was to be taken to the Executive Mansion. If the departure drew any notice, he reasoned, it would be assumed that Lincoln was simply paying a visit to the governor’s residence. As Curtin made his way back inside, he was joined by Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln’s friend and self-appointed bodyguard. Drawing Lamon aside, Curtin asked if he was armed. Lamon “at once uncovered a small arsenal of deadly weapons. In addition to a pair of heavy revolvers, he had a slung-shot and brass knuckles and a huge knife nestled under his vest.” The slung-shot, a crude street weapon involving a weight tied to a wrist strap, was popular at that time among street gangs.

When Lincoln emerged, Judd would report, he carried a shawl draped over his arm. The shawl, according to Lamon, would help mask Lincoln’s features as he emerged from the hotel. Curtin led the group toward the side entrance of the hotel, where a carriage waited. As they made their way along the corridor, Judd whispered to Lamon: “As soon as Mr. Lincoln is in the carriage, drive off. The crowd must not be allowed to identify him.”

Reaching the side door, Lamon climbed into the carriage first, then turned to help Lincoln and Curtin. The first phase of Pinkerton’s scheme had gone according to plan.

Among the crew of Felton’s railroad, it appeared that the most notable thing to occur on the evening of February 22 had been a set of special instructions concerning the 11 p.m. train from Philadelphia. Felton himself had directed the conductor to hold his train at the station to await the arrival of a special courier, who would hand off a vitally important parcel. Under no circumstance could the train depart without it, Felton warned, “as this package must go through to Washington on tonight’s train.”

In fact, the package was a decoy, part of an elaborate web of bluffs and blinds that Pinkerton had constructed. In order to make the package convincing, Felton would recall, he and Pinkerton assembled a formidable-looking parcel done up with an impressive wax seal. Inside was a stack of useless old railroad reports. “I marked it ‘Very important — To be delivered, without fail, by eleven o’clock train,’” Felton recalled.

Lincoln would have to cover more than 200 miles in a single night, running in darkness for most of the route, with two changes of train. The revised scheme would accomplish Pinkerton’s original goal of bringing Lincoln through Baltimore earlier than expected. In addition, Lincoln would make his approach to the city on a different rail line, and arrive at a different station.

Though Lincoln would be making the first leg of his trip in a private train, Pinkerton could not risk using special equipment for the remaining two segments of the journey, as it would draw attention to Lincoln’s movements to have an unscheduled special on the tracks that night. In order to travel anonymously, Lincoln would have to ride on regular passenger trains, gambling that the privacy of an ordinary sleeping compartment would be sufficient to conceal his presence.

Having charted this route, Pinkerton now confronted a scheduling problem. The train carrying Lincoln from Harrisburg would likely not reach Philadelphia in time to connect with the second segment of the journey, the 11 p.m. train to Baltimore. Felton’s decoy parcel, it was hoped, would hold the Baltimore-bound train at the depot without drawing undue suspicion, until Lincoln could be smuggled aboard. If all went according to plan, Lincoln would arrive in Baltimore in the dead of night. His sleeper car would be unhitched and drawn by horse to Camden Street Station, where it would be coupled to a Washington-bound train.

The task of getting Lincoln safely aboard the Baltimore-bound passenger train would be especially delicate, as it would have to be done in plain view of passengers and crew. For this, Pinkerton needed a second decoy, and he counted on Kate Warne to supply it. In Philadelphia, Warne made arrangements to reserve four double berths on the sleeper car at the back of the train. She had been instructed by Pinkerton to “get in the sleeping car and keep possession” until he arrived with Lincoln.

Once aboard that night, Warne flagged down a conductor and pressed some money into his hand. She needed a special favor, she said, because she would be traveling with her “invalid brother,” who would retire immediately to his compartment and remain there behind closed blinds. A group of spaces, she implored, must be held at the back of the train, to ensure his comfort and privacy. The conductor, seeing the concern in the young woman’s face, nodded his head and took up a position at the rear door of the train, to fend off any arriving passengers.

***

In Harrisburg, arrangements were carried out by a late addition to Pinkerton’s network: George C. Franciscus, a superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Pinkerton had confided in Franciscus the previous day, since the last-minute revision of his plan required Lincoln to make the first leg of his journey on Franciscus’ line. “I had no hesitation in telling him what I desired,” Pinkerton reported, because he had worked with Franciscus previously and knew him to be “a true and loyal man.”

A Pennsylvania Railroad fireman, Daniel Garman, later recalled that Franciscus came hurrying up to him, “very much excited,” with orders to get a special train charged and ready. “I quick went and oiled up the engine and lighted the head light and turned up my fire,” Garman recalled. As he finished, he looked out to see engineer Edward Black running along the track at full speed, having been ordered by Franciscus to report for emergency duty. Black hopped up into the cab and scrambled to make ready, apparently under the impression that a private train was needed to carry a group of railroad executives to Philadelphia. They ran the two-car special a mile south toward Front Street, as instructed, and idled at a track crossing to wait for their passengers.

Franciscus, meanwhile, had circled back to the Jones House in a carriage, pulling up just as Governor Curtin, Lamon and Lincoln himself—his appearance masked by his unfamiliar hat and shawl—emerged from the side entrance of the hotel. As the door closed behind the passengers, Franciscus flicked his whip and started off in the direction of the railroad tracks.

At the Front Street crossing, Black and Garman looked on as a tall figure, escorted by Franciscus, quietly alighted from a carriage and made his way down the tracks to the saloon car. Lincoln’s 250-mile dash to Washington was underway.

Even as the train vanished into the darkness, a lineman directed by Pinkerton was climbing a wooden utility pole two miles south of town, cutting off telegraph communication between Harrisburg and Baltimore. Governor Curtin, meanwhile, returned to the Executive Mansion and spent the evening turning away callers, so as to give the impression that Lincoln was resting inside.

On board the train, Black and Garman were making the best time of their lives. All trains had been shunted off the main line to allow the special an unimpeded run.

In the passenger coach, Lincoln and his fellow travelers sat in the dark, so as to reduce the chance that the president-elect would be spotted during watering stops. The precaution wasn’t entirely successful. At one of the stops, as Garman bent to connect a hose pipe, he caught sight of Lincoln in the moonlight streaming through the door of the coach. He ran forward to tell Black that “the rail-splitter was on the train,” only to be muzzled by Franciscus, who warned him not to say a word. “You bet I kept quiet then,” Garman recalled. Climbing into the cab alongside Black, Garman could not entirely contain his excitement. He cautiously asked his colleague if he had any idea what was going on in the saloon car. “I don’t know,” the engineer replied, “but just keep the engine hot.” By that time, Black may have had his own suspicions. “I have often wondered what people thought of that short train whizzing through the night,” Black would later say. “A case of life and death, perhaps, and so it was.”

In Philadelphia, Pinkerton readied himself for the next phase of the operation. At the Pennsylvania Railroad’s West Philadelphia depot, Pinkerton left a closed carriage waiting at the curb. He was joined by H.F. Kenney, another of Felton’s employees. Kenney reported that he had just come from the PW&B depot across town, where he had issued orders to hold the Baltimore-bound train for Felton’s “important parcel.”

Just after 10, the squeal of brake blocks and hiss of steam announced the arrival of the two-car special from Harrisburg, well ahead of schedule. In fact, Garman and Black’s heroic efforts had created a problem for Pinkerton. As he stepped forward and exchanged hushed greetings with Lincoln, Pinkerton realized that the early arrival of the Harrisburg train left him with too much time. The Baltimore-bound train was not scheduled to leave for nearly an hour; Felton’s depot was only three miles away.

It wouldn’t do to linger at either train station, where Lincoln might be recognized, nor could he be seen on the streets. Pinkerton decided that Lincoln would be safest inside a moving carriage. To avoid rousing the carriage driver’s suspicions, he told Kenney to distract him with a time-consuming set of directions, “driving northward in search of some imaginary person.”

As Franciscus withdrew, Pinkerton, Lamon and Lincoln, his features partly masked by his shawl, took their seats in the carriage. “I took mine alongside the driver,” Kenney recalled, and gave a convoluted set of orders that sent them rolling in aimless circles through the streets.

Lincoln was sandwiched between the small, wiry Pinkerton and the tall, stocky Lamon. “Mr. Lincoln said that he knew me, and had confidence in me and would trust himself and his life in my hands,” Pinkerton recalled. “He evinced no sign of fear or distrust.”

At last, Pinkerton banged on the roof of the carriage and barked out an order to make straight for the PW&B depot. Upon arrival, Lamon kept watch from the rear as Pinkerton walked ahead, with Lincoln “leaning upon my arm and stooping...for the purpose of disguising his height.” Warne came forward to lead them to the sleeper car, “familiarly greeting the President as her brother.”

As the rear door closed behind the travelers, Kenney made his way to the front of the train to deliver Felton’s decoy parcel. Pinkerton would claim that only two minutes elapsed between Lincoln’s arrival at the depot and the departure of the train: “So carefully had all our movements been conducted, that no one in Philadelphia saw Mr. Lincoln enter the car, and no one on the train, except his own immediate party—not even the conductor—knew of his presence.”

***

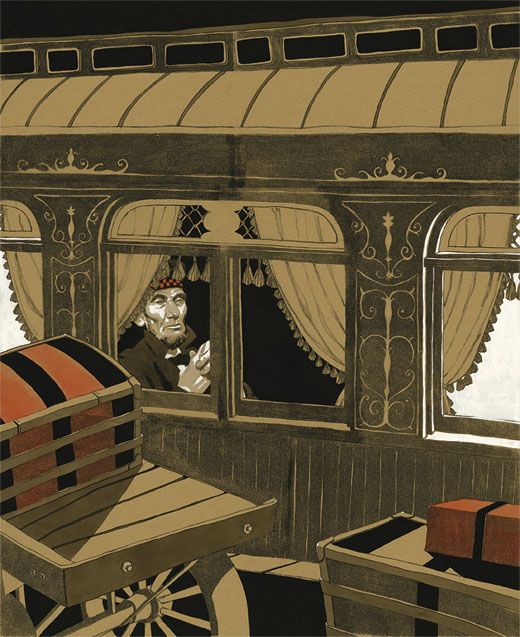

The journey from Philadelphia to Baltimore was expected to take four and a half hours. Warne had managed to secure the rear half of the car, four pairs of berths in all, but there was little privacy. Only a curtain separated them from the strangers in the forward half, so the travelers were at pains to avoid drawing attention. Lincoln remained out of sight behind hanging drapes, but he would not be getting much rest that night. As Warne noted, he was “so very tall that he could not lay straight in his berth.”

As the train pressed on toward Baltimore, Pinkerton, Lamon and Warne settled into their berths. Lamon recalled that Lincoln relieved the tension by indulging in a joke or two, “in an undertone,” from behind his curtain. “He talked very friendly for some time,” said Warne. “The excitement seemed to keep us all awake.” Apart from Lincoln’s occasional comments, all was silent. “None of our party appeared to be sleepy,” Pinkerton noted, “but we all lay quiet.”

Pinkerton’s nerves kept him from lying still for more than a few minutes at a time. At regular intervals he stepped through the rear door of the car and kept watch from the back platform, scanning the track.

At 3:30 in the morning, Felton’s “night line” train steamed into Baltimore’s President Street depot on schedule. Warne took her leave of Lincoln while the train idled at the station, as she was no longer needed to pose as the sister of the “invalid traveler.”

Pinkerton listened intently as rail workers uncoupled the sleeper and hitched it to a team of horses. With a sudden lurch, the car began its slow, creaking progress through the streets of Baltimore toward Camden Street Station, just over a mile away. “The city was in profound repose as we passed through,” Pinkerton remarked. “Dark- ness and silence reigned over all.”

Pinkerton had calculated that Lincoln would spend only 45 minutes in Baltimore. Arriving at Camden Street Station, however, he found that they would have to endure an unexpected delay, owing to a late-arriving train. For Pinkerton, who feared that even the smallest variable could upset his entire plan, the wait was agonizing. At dawn, the busy terminus would spring to life with the “usual bustle and activity.” With every passing moment, discovery became more likely. Lincoln, at least, seemed perfectly sanguine about the situation. “Mr. Lincoln remained quietly in his berth,” Pinkerton said, “joking with rare good humor.”

As the wait dragged on, however, Lincoln’s mood darkened briefly. Now and then, Pinkerton said, “snatches of rebel harmony” would reach their ears, sung by passengers waiting at the depot. At the sound of a drunken voice roaring through a chorus of “Dixie,” Lincoln turned to Pinkerton and offered a somber reflection: “No doubt there will be a great time in Dixie by and by.”

As the skies began to brighten, Pinkerton peered through the blinds for a sign of the late-arriving train that would carry them the rest of the way to Washington. Unless it came soon, all advantage would be swept away by the rising sun. If Lincoln were to be discovered now, pinned to the spot at Camden Street and cut off from any assistance or reinforcements, he would have only Lamon and Pinkerton to defend him. If a mob should assemble, Pinkerton realized, the prospects would be very bleak indeed.

As the detective weighed his limited options, he caught the sound of a familiar commotion outside. A team of rail workers had arrived to couple the sleeper to a Baltimore & Ohio train for the third and final leg of the long journey. “At length the train arrived and we proceeded on our way,” Pinkerton later recorded stoically, perhaps not wishing to suggest that the outcome had ever been in doubt. Lamon was only slightly less reserved: “In due time,” he reported, “the train sped out of the suburbs of Baltimore, and the apprehensions of the President and his friends diminished with each welcome revolution of the wheels.” Washington was now only 38 miles away.

At 6 a.m. on February 23, a train pulled into the Baltimore & Ohio depot in Washington, and three stragglers—one of them tall and lanky, wrapped in a thick traveling shawl and soft, low-crowned hat—emerged from the end of the sleeping car.

Later that morning, in Baltimore, as Davies accompanied Hillard to the appointed assassination site, rumors swept the city that Lincoln had arrived in Washington. “How in hell,” Hillard swore, “had it leaked out that Lincoln was to be mobbed in Baltimore?” The president-elect, he told Davies, must have been warned, “or he would not have gone through as he did.”

Decades later, in 1883, Pinkerton would quietly sum up his exploits. “I had informed Mr. Lincoln in Philadelphia that I would answer with my life for his safe arrival in Washington,” Pinkerton recalled, “and I had redeemed my pledge.”

***

Although Harry Davies likely continued in Pinkerton’s employ, the records documenting his dates of service were lost in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

Kate Warne succumbed to a lingering illness in 1868 at age 35. She was buried in the Pinkerton family plot.

Ward Hill Lamon was in Richmond, Virginia, on the night of Lincoln’s murder in 1865. He would accompany the funeral train to Springfield.

During the Civil War, Allan Pinkerton served as chief of the Union Intelligence Service in 1861 and 1862. When news of Lincoln’s assassination reached him, he wept. “If only,” Pinkerton mourned, “I had been there to protect him, as I had done before.” He presided over the Pinkerton National Detective Agency until his death at age 63 in 1884.

Excerpted from The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War by Daniel Stashower. Copyright (c) 2013. With the permission of the publisher, Minotaur Books