The White House’s First Celebrity Dog

Bo, the Obama’s First Pooch, has a legacy to live up to in Laddie Boy, the family pet of President Harding

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Laddie-Boy-silver-portrait-new-631.jpg)

UPDATED: April 13, 2009

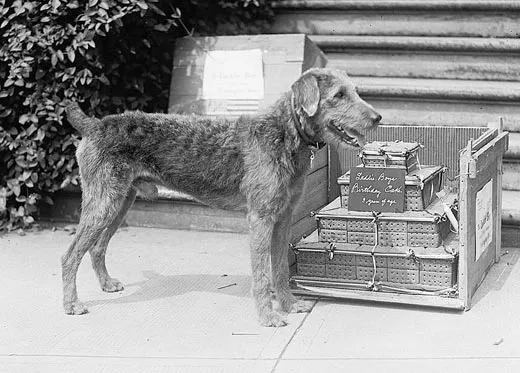

Over the Easter weekend, a carefully guarded White House secret leaked out: The Obama girls, Malia and Sasha, finally have a puppy. His name is Bo, and he’s a six-month-old Portuguese water dog. Just hours after his identity was revealed, Bo was already an Internet sensation. But he won't be the first celebrity White House dog. That honor goes to Laddie Boy, an Airedale terrier who was the pet of President Warren G. Harding and his wife, Florence.

Though there were many presidential pets before him, Laddie Boy was the first to receive regular coverage from newspaper reporters. "While no one remembers him today, Laddie Boy's contemporary fame puts Roosevelt's Fala, LBJ's beagles and Barney Bush in the shade," says Tom Crouch, a Smithsonian Institution historian. "That dog got a huge amount of attention in the press. There have been famous dogs since, but never anything like this."

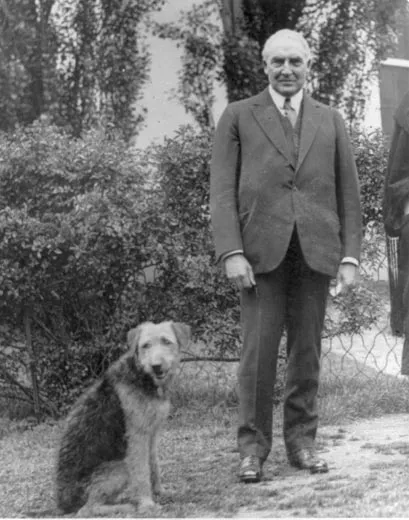

During their time in the White House, from 1921 to 1923, the Hardings included their dog in almost every aspect of their daily lives. When Harding golfed with friends, Laddie Boy tagged along. During cabinet meetings, the dog sat in (perched on his own chair). At fundraising events, the first lady frequently had Laddie Boy make appearances. The dog was such a prominent White House personality that the Washington Star and the New York Times seemed to run stories about the terrier almost daily in the months after Harding took office. In a 39-day period in the spring of 1921, these are just some of the headlines that appeared in the Times:

"Gets Airedale as Mascot"

"Laddie Boy a Newsboy"

"Trees White House Cat"

"Laddie Boy Gets Playmate"

Born on July 26, 1920, at the Caswell Kennels in Toledo, Ohio, Laddie Boy was 6 months old when he arrived at the White House on March 5, 1921, the day after Harding's inauguration. A sitting U.S. senator from Marion, Ohio, Harding had won the 1920 presidential election with 60 percent of the popular vote. Harding, who had brought his relaxed and informal work style to the presidency, instructed his staff to bring Laddie Boy to him as soon as he was delivered to the White House. The staff obeyed, interrupting Harding's first cabinet meeting to unveil the terrier. "With many manifestations of pleasure, the President led his new pet into his office, where he made himself at home," wrote a Times reporter on March 5.

Will the future Obama dog get the kind of Oval Office access that Laddie Boy had? If Barack Obama is as besotted with his dog as Harding was with Laddie Boy, possibly. But it's probably fair to say that Obama would not be getting a dog had he not promised his daughters a puppy to make up for the inconveniences they endured during the presidential campaign. "I guess I'm a little disappointed that he didn't have a dog previously," says Ronnie Elmore, associate dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine at Kansas State University, who has developed a side career as a historian of presidential pets. "And then that it has taken so long to get the dog. There are kennels in the White House, and a dog could be assimilated into the White House scene very quickly and without any real responsibility for the Obamas other than to play with the dog once in a while."

The White House kennels existed in Laddie Boy's day, but the Airedale seems to have spent little time there. He was too busy roaming the White House living quarters, where the Hardings doted on him like the child they never had—together. Before her marriage to Harding, Florence had struggled to support herself as an unwed mother after giving birth to a son when she was 20. When the boy was 4 years old, he was sent to live with Florence's wealthy parents, who raised the child as their son. As for Harding, throughout his marriage, he relentlessly—and successfully—pursued sexual relationships with other women, at least one of whom bore him a child.

Tall and handsome, Harding certainly looked presidential, and he was an eloquent speaker, but he likely would not have won the White House without the help of the ambitious Florence, who was five years his senior. Before beginning his political career, Harding had been the owner of a struggling newspaper in Marion. After marrying Harding, Florence did her best to bring order to her husband's private and professional lives. Under her expert management, Harding's newspaper became profitable. No wonder Harding referred to his wife as "the Duchess." "Psychologically, they were a whale of an interesting couple," says historian Crouch.

However much Florence tried to keep her husband on the right path, she was unable to prevent the scandals that would rock his administration. Harding appointed several of his friends to his cabinet, many of whom were not worthy of a president's trust. While Harding's cabinet included the future 31st president, Herbert Hoover, as secretary of commerce, it also had Albert Fall as secretary of interior, who rented federal land to oil companies in exchange for personal loans.

While Harding was a flawed president, he was, in the words of a New York Times story published on March 12, "kindly, simple, neighborly and genuine." His kindness found expression in love for animals; indeed both Hardings supported the humane treatment of all creatures. In an editorial that Harding had authored while still editor of the Marion Star, he wrote: "Whether the Creator planned it so, or environment and human companionship have made it so, men may learn richly through the love and fidelity of a brave and devoted dog." The president took such pleasure in Laddie Boy that he had 1,000 bronze miniatures made in the dog's image shortly after taking office. Like a proud father handing out cigars to celebrate the birth of a child, Harding had the dog statuettes sent to his political supporters in Washington, D.C., and to those back in Ohio.

The Laddie Boy miniatures have become a rare find for collectors of presidential memorabilia, commanding between $1,500 and $2,000, says Kansas State veterinarian Elmore. He feels fortunate to have one in his collection. "I had been looking for one all over the country and on eBay," he says. "And one afternoon my wife was at an antiques store here in Manhattan, Kansas, and just as she was leaving, she looked down and saw Laddie Boy in a glass case. And she just about fainted. It turns out that there was an elderly person that lived here who had died, and at the estate sale, the antique's dealer bought a box of junk, and Laddie Boy was in there."

Harding enjoyed his pet's fame; in fact, he cultivated it by writing letters to the press pretending to be Laddie Boy. But the president drew the line at commercializing his dog. "During the Harding administration, numerous toy manufacturers sent letters to the White House asking permission to have exclusive rights to produce a stuffed toy in the likeness of Laddie Boy," says Melinda Gilpin, historic site manager of the Harding Home State Memorial in Marion. "Harding refused to endorse any such endeavor." At least one company did go ahead and manufacture a stuffed animal Laddie Boy, an example of which is on display at the Harding Home.

For those Harding admirers for whom a stuffed toy Laddie Boy was not enough, they could always get a real Airedale. Sure enough, the breed's popularity grew during the Harding White House. Perhaps we ought to brace ourselves for an increased demand for either labradoodles or Portuguese water dogs. (During an interview with ABC news anchor George Stephanopoulos that aired on January 11, Obama said that his family was favoring these two breeds.)

"Airedales are very people-oriented and want to please their masters," says Kansas State's Elmore. Laddie Boy did his best to keep the Hardings happy. He brought the newspaper to the president at breakfast each morning. He did charitable work at the behest of Florence. On April 20, 1921, the Times published a story reporting that the terrier had been invited to lead an animal parade that would benefit the Humane Education Society in Washington, D.C. The unidentified reporter wrote: "Announcement that Laddie Boy had accepted the invitation was made today at the White House." As if Laddie Boy had his own press secretary!

Occasionally, though, the Airedale balked at life in the presidential fishbowl. Like other administrations before them, the Hardings continued the tradition of the annual Easter Egg Roll, held on the White House lawn. On April 18, 1922, the Times published a story about the well-attended event: "It wouldn't have been a children's party without Laddie Boy, [who] was the first resident of the White House to appear on the south portico. His keeper let him loose down the steps, but so many were the little hands put out to pat him that Laddie Boy raced back and spent the remainder of the morning sitting proudly on a table. There was almost as large a crowd of youngsters watching the Harding Airedale as there was around the five truckloads of bottled pop on the driveway."

Fourteen months later, Harding undertook a cross-country train tour, in part to distract the American public from allegations of wrongdoing by some of his cabinet secretaries. Harding, who had an enlarged heart, had been in failing health before leaving Washington, D.C., and during the trip, his cardiovascular troubles became more acute. On August 2, 1923, the nation's 29th president died in his room at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco.

The Hardings had not taken Laddie Boy on the whistle-stop tour, instead leaving him in the care of his White House handler. The day after Harding died, the Associated Press ran a story about the dog: "There was one member of the White House household today who could not quite comprehend the air of sadness which hung over the Executive Mansion. It was Laddie Boy, President Harding's Airedale friend and companion. Of late he has been casting an expectant eye and cocking a watchful ear at the motor cars which roll up on the White House drive. For, in his dog sense way, he seems to reason that an automobile took [the Hardings] away, so an automobile must bring them back. White House attachés shook their heads and wondered how they were going to make Laddie Boy understand."

Sympathy for the grieving dog inspired a woman named Edna Bell Seward to write the lyrics for a song titled "Laddie Boy, He's Gone," which was available on sheet music and piano roll. The third verse reads:

As you wait—brown eyes aglisten

For a master's face that's gone

He is smiling at you, Laddie

From the peace of the Beyond

While making arrangements to leave the White House, Florence gave Laddie Boy to Harry Barker, the Secret Service agent who had been assigned to protect her. Barker had been like a son to Florence, and when his White House assignment ended, he was transferred to the agency's Boston office. Laddie Boy settled into a new life at the home of Barker and his wife in Newtonville, Massachusetts.

To honor Harding's background as a newspaperman, more than 19,000 newsboys around the country each donated a penny for a memorial to the fallen president. The pennies were melted down and cast into a life-size sculpture of Laddie Boy by Boston-based sculptor, Bashka Paeff. While Paeff worked on the sculpture, Laddie Boy was required to complete 15 sittings. Today, the sculpture is part of the collection at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History (the artifact is not currently on display).

Florence Harding died on November 21, 1924, at a sanitarium in Marion. She was survived by Laddie Boy, who passed away on January 22, 1929, nearly six years after he had reigned as first dog. Ever the faithful chronicler of Laddie Boy's charmed life, the New York Times ran a story describing the terrier as "magnificent," and reporting that the "end came while the dog, ailing for many months of old age, rested his head on the arms of Mrs. Barker." The Airedale was then buried at an undisclosed location in Newtonville.

Laddie Boy's celebrity as a presidential pet might never be surpassed—even by the Obama dog. Certainly, current news-gathering technology makes filing stories now a lot easier than it was in 1921. But with our country fighting two wars and the U.S. economy in turmoil, it's hard to imagine New York Times reporters giving as much sustained coverage to the Obama dog as they did to Laddie Boy. In the end, though, who can resist a cute dog story?