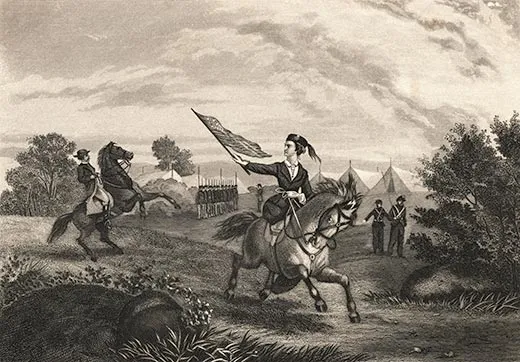

The Women Who Fought in the Civil War

Hundreds of women concealed their identities so they could battle alongside their Union and Confederate counterparts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/women-civil-war-Sarah-Edmonds-Frank-Thompson-631.jpg)

Even though women weren’t legally allowed to fight in the Civil War, it is estimated that somewhere around 400 women disguised themselves as men and went to war, sometimes without anyone ever discovering their true identities.

Bonnie Tsui is the author of She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers in the Civil War, which tells the stories of some of these women. I spoke with the San Francisco-based writer about her research into the seldom-acknowledged participation of women in the Civil War.

Why weren’t women allowed to fight in the Civil War?

At the time, women weren’t perceived as equals by any stretch of the imagination. It was the Victorian era and women were mostly confined to the domestic sphere. Both the Union and Confederate armies actually forbade the enlistment of women. I think it was during the Revolutionary War that they established women as nurses because they needed help on the front when soldiers were injured. But women weren’t allowed to serve in combat. Of course, women did disguise themselves and enlist as men. There is evidence that they also did so during the Revolutionary War.

How did they do it?

Honestly, the lore is that the physical exams were not rigorous at all. If you had enough teeth in your head and could hold a musket, you were fine. The funny thing is, in this scenario, a lot of women didn’t seem any less manly than, for example, the teenage boys who were enlisting. At the time, I believe the Union had an official cutoff age of 18 for soldiers, but that was often flouted and people often lied. They had a lot of young guys and their voices hadn’t changed and their faces were smooth. The Confederacy never actually established an age requirement. So [women] bound their breasts if they had to, and just kind of layered on clothes, wore loose clothing, cut their hair short and rubbed dirt on their faces. They also kind of kept to themselves. The evidence that survived often describes them as aloof. Keeping to themselves certainly helped maintain the secret.

When the women were found out, did it provoke an uproar?

Even in the cases where these women were found out as soldiers, there does not actually seem to be much uproar. More or less, they were just sent home. The situations in which they were found out were often medical conditions; they were injured, or they got sick from dysentery or chronic diarrhea. Disease killed many more soldiers than bullets did. You’re sitting in camps among all these people who are in close quarters. There wasn’t a lot of knowledge then about bacterial infection and particularly in close quarters there wasn’t much chance to prevent it.

There is some documentation that shows that some soldiers that were discovered as women were briefly imprisoned. In the letter of one [female disguised as a male] prison guard, it said that there were three [other] women in the prison, one of whom was a major in the Union Army. She had gone to battle with her fellow men and was jailed because she was a woman. It’s really interesting hearing about her being a woman, disguised as a man, standing as a prison guard for a woman imprisoned for doing the same thing.

What was the motivation on the part of the women you studied? Did it seem pretty much the same as the men?

It absolutely did. I think by all accounts, the women seemed honestly to want to fight in the war for the same reasons as men, so that would range from patriotism, to supporting their respective causes, for adventure, to be able to leave home, and to earn money. Some of the personal writings that survive show that they were also running away from family lives that were really unsatisfying. You can imagine that perhaps they felt trapped at home or weren’t able to marry and felt that they were financial burdens to their families. If you profile the substantiated cases of these women, they were young and often poor and from farming families, and that is the exact profile of the typical male volunteer. If you think about that, girls growing up on a farm would have been accustomed to physical labor. Maybe they even would have worn boys’ clothing to do farm chores. But then there are also some cases in which women follow their husbands or a brother into battle, and so there are at least a couple of those cases in which female soldiers were on record of enlisting with their relative.

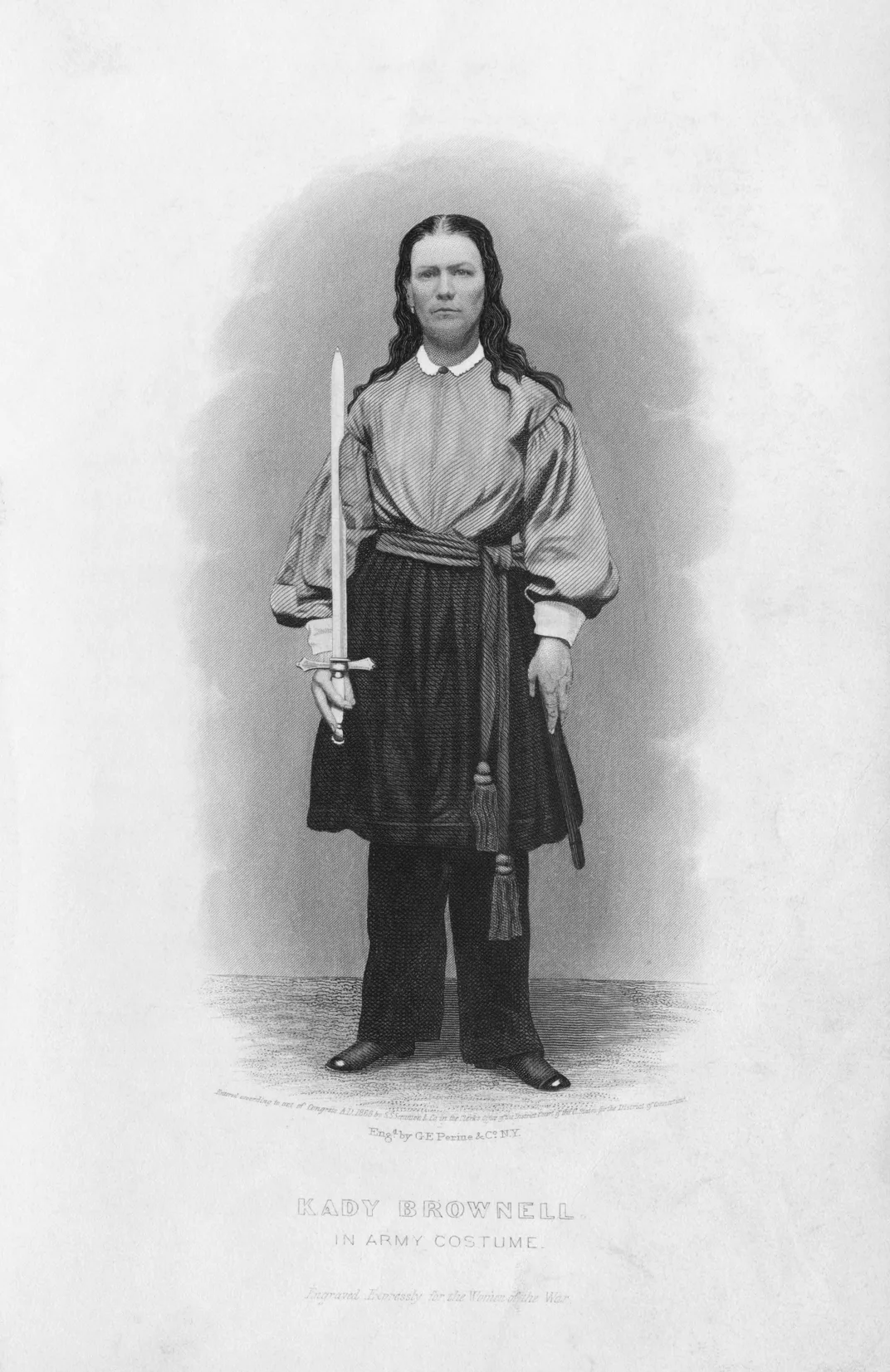

What duties did the women perform?

They did everything that men did. They worked as scouts, spies, prison guards, cooks, nurses and they fought in combat. One of the best-documented female soldiers is Sarah Edmonds—her alias was Frank Thompson. She was a Union soldier, and she worked for a long time during the war as a nurse. You often can’t really draw a delineation between “civilian workers” and battle, because these people had to be in battle, tending to soldiers. They were often on the field or nearby trying to get to the wounded, so you could argue that it was just as dangerous for them to work as nurses as to be actively shooting and emptying gunfire.

What is another one of your favorite stories from your research?

One of my favorite stories of the Civil War era is of Jennie Hodgers, and she fought as Albert Cashier. She enlisted in Illinois and she fought the entire Civil War without being discovered and ended up living out the rest of her life as a man for another fifty years. She even ended up receiving a military pension and living at the sailors’ and soldiers’ home in Illinois as a veteran. The staff at the home kept her secret for quite sometime, even after they discovered that she was a woman.

Even though it seems pretty outstanding that women were disguising themselves as men and going off to fight, it seems like actually they were accepted amongst their peers. This kind of loyalty to your fellow soldier in battle did in certain cases transcend gender. It’s pretty amazing; there was a lot of respect.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)