The Women Who Mapped the Universe and Still Couldn’t Get Any Respect

At the beginning of the 20th century, a group of women known as the Harvard Observatory computers helped revolutionize the science of astronomy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130918012130pickering-470.jpg)

In 1881, Edward Charles Pickering, director of the Harvard Observatory, had a problem: the volume of data coming into his observatory was exceeding his staff’s ability to analyze it. He also had doubts about his staff’s competence–especially that of his assistant, who Pickering dubbed inefficient at cataloging. So he did what any scientist of the latter 19th century would have done: he fired his male assistant and replaced him with his maid, Williamina Fleming. Fleming proved so adept at computing and copying that she would work at Harvard for 34 years–eventually managing a large staff of assistants.

So began an era in Harvard Observatory history where women—more than 80 during Pickering’s tenure, from 1877 to his death in 1919— worked for the director, computing and cataloging data. Some of these women would produce significant work on their own; some would even earn a certain level of fame among followers of female scientists. But the majority are remembered not individually but collectively, by the moniker Pickering’s Harem.

The less-than-enlightened nickname reflects the status of women at a time when they were–with rare exception–expected to devote their energies to breeding and homemaking or to bettering their odds of attracting a husband. Education for its own sake was uncommon and work outside the home almost unheard of. Contemporary science actually warned against women and education, in the belief that women were too frail to handle the stress. As doctor and Harvard professor Edward Clarke wrote in his 1873 book Sex in Education, “A woman’s body could only handle a limited number of developmental tasks at one time—that girls who spent to much energy developing their minds during puberty would end up with undeveloped or diseased reproductive systems.”

Traditional expectations of women slowly changed; six of the “Seven Sisters” colleges began admitting students between 1865 and 1889 (Mount Holyoke opened its doors in 1837). Upper-class families encouraged their daughters to participate in the sciences, but even though women’s colleges invested more in scientific instruction, they still lagged far behind men’s colleges in access to equipment and funding for research. In a feeble attempt to remedy this inequality, progressive male educators sometimes partnered with women’s institutions.

Edward Pickering was one such progressive thinker–at least when it came to opening up educational opportunities. A native New Englander, he graduated from Harvard in 1865 and taught physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he revolutionized the method of scientific pedagogy by encouraging students to participate in experiments. He also invited Sarah Frances Whiting, an aspiring young female scientist, to attend his lectures and to observe his experiments. Whiting used these experiences as the basis for her own teaching at Wellesley College, just 13 miles from Pickering’s classroom at MIT.

Pickering’s approach toward astronomic techniques was also progressive; instead of relying solely on notes from observations made by telescope, he emphasized examining photographs–a type of observation known today as astrophotography, which uses a camera attached to a telescope to take photos. The human eye, he reasoned, tires with prolonged observation through a telescope, and a photograph can provide a clearer view of the night sky. Moreover, photographs last much longer than bare-eye observations and notes.

Early astrophotography used the technology of the daguerreotype to transfer images from a telescope to a photographic plate. The process was involved and required long exposure time for celestial objects to appear, which frustrated astronomers. Looking for a more efficient method, Richard Maddox revolutionized photography by creating a dry plate method, which unlike the wet plates of earlier techniques, did not have to be used immediately–saving astronomers time by allowing them to use dry plates that had been prepared before the night of observing. Dry plates also allowed for longer exposure times than wet plates (which ran the risk of drying out), providing for greater light accumulation in the photographs. Though the dry plates made the prep work more efficient, their sensitivity to light still lagged behind what astronomers desired. Then, in 1878, Charles Bennett discovered a way to increase the sensitivity to light, by developing them at 32 degrees Celsius. Bennet’s discovery revolutionized astrophotography, making the photographs taken by the telescopes nearly as clear and useful as observations seen with the naked eye.

When Pickering became director of the Harvard Observatory in 1877, he lobbied for the expansion of the observatory’s astrophotography technology, but it wasn’t until the 1880s, when the technology greatly improved, that these changes were truly implemented. The prevalence of photography at the observatory rose markedly, creating a new problem: there was more data than anyone had time to interpret. The work was tedious, duties thought to lend themselves to a cheaper and less-educated workforce thought to be capable of classifying stars rather than observing them: women. By employing his female staff to engage in this work, Pickering certainly made waves in the historically patriarchal realm of academia.

But it’s hard to tout Pickering as a wholly progressive man: by limiting the assistants’ work to largely clerical duties, he reinforced the era’s common assumption that women were cut out for little more than secretarial tasks. These women, referred to as “computers,” were the only way that Pickering could achieve his goal of photographing and cataloging the entire night sky.

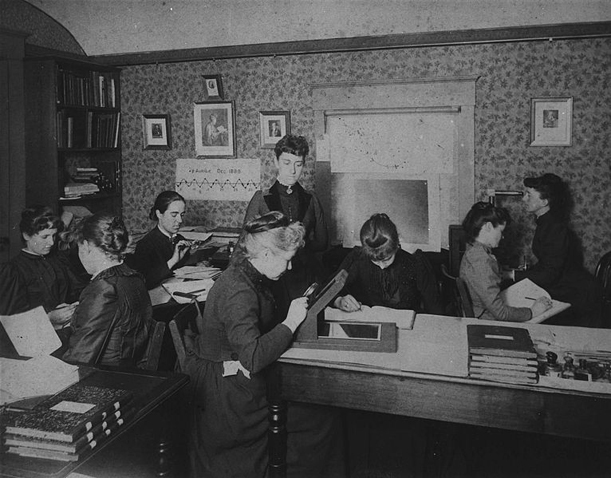

All told, more than 80 women worked for Pickering during his tenure at the Harvard Observatory (which extended to 1918), putting in six-day weeks poring over photographs, and earning 25 to 50 cents an hour (half what a man would have been paid). The daily work was largely clerical: some women would reduce the photographs, taking into account things like atmospheric refraction, in order to render the image as clear and unadulterated as possible. Others would classify the stars through comparing the photographs to known catalogs. Others cataloged the photographs themselves, making careful notes of each image’s date of exposure and the region of the sky. The notes were then meticulously copied into tables, which included the star’s location in the sky and its magnitude. It was a grind. As Fleming noted in her diary:

In the Astrophotographic building of the Observatory, 12 women, including myself, are engaged in the care of the photographs…. From day to day my duties at the Observatory are so nearly alike that there will be little to describe outside ordinary routine work of measurement, examination of photographs, and of work involved in the reduction of these observations.

Pickering’s assistants examine photographs for astronomical data. Photo from the Harvard College Observatory.

But regardless of the unequal pay and distribution of duties, this work was incredibly important; the data provided the empirical foundations for larger astronomical theory. Pickering allowed some women to make telescopic observations, but this was the exception rather than the rule. Mostly, women were barred from producing real theoretical work and were instead relegated to analyzing and reducing the photographs. These reductions, however, served as the statistical basis for the theoretical work done by others. Chances for great advancement were extremely limited. Often the most a woman could hope for within the Harvard Observatory would be a chance to oversee less-experienced computers. That’s what Williamina Fleming was doing when, after almost 20 years at the observatory, she was appointed Curator of Astronomical Photos.

One of Pickering’s computers, however, would stand out for her contribution to astronomy: Annie Jump Cannon, who devised a system for classifying stars that is still used today. But as an article written in The Woman Citizen‘s June 1924 issue reported: “The traffic policeman on Harvard Square does not recognize her name. The brass and parades are missing. She steps into no polished limousine at the end of the day’s session to be driven by a liveried chauffeur to a marble mansion.”

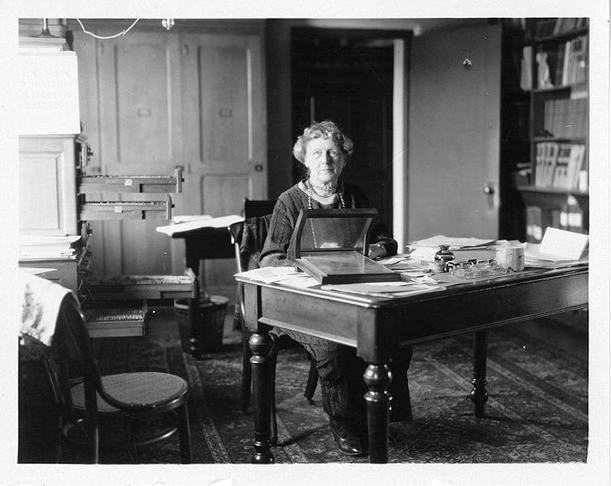

Annie Jump Cannon at her desk at the Harvard Observatory. Photo from the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Cannon was born in Dover, Delaware, on December 11, 1863. Her father, a shipbuilder, had some knowledge of the stars, but it was her mother who passed on her own childhood interest in astronomy. Both parents nourished her love of learning, and in 1880, when she enrolled at Wellesley College, she became one of the first young women from Delaware to go away to college. At Wellesley, she took classes under Whiting, and while doing graduate work there she helped Whiting conduct experiments on x-rays. But when the Harvard Observatory began to gain fame for its photographic research, Cannon transferred to Radcliffe College in order to work with Pickering, beginning in 1896. Pickering and Fleming had been working on a system for classifying stars based on their temperatures; Cannon, adding to work done by fellow computer Antonia Maury, greatly simplified that system, and in 1922, the International Astronomical Union adopted it as the official classification system for stars.

In 1938, two years before Cannon retired and three years before she died, Harvard finally acknowledged her by appointing her the William C. Bond Astronomer. During Pickering’s 42-year tenure at the Harvard Observatory, which ended only a year before he died, in 1919, he received many awards, including the Bruce Medal, the Astronomical Society of the Pacific’s highest honor. Craters on the moon and on Mars are named after him.

And Annie Jump Cannon’s enduring achievement was dubbed the Harvard—not the Cannon—system of spectral classification.

Sources: “Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College, Volume XXIV,” on Take Note, An Exploration of Note-Taking in Harvard University Collections, 2012. Accessed September 3, 2013; “Annie Cannon (1863-1914)” on She Is An Astronomer, 2013. Accessed September 9, 2013; “Annie Jump Cannon” on Notable Name Database, 2013. Accessed September 9, 2013; “Brief History of Astrophotography” on McCormick Museum, 2009. Accessed September 18, 213; “The ‘Harvard Computers’” on WAMC, 2013. Accessed September 3, 2013; “The History of Women and Education” on the National Women’s History Museum, 207. Accessed August 19, 2013; Kate M. Tucker. “Friend to the Stars” in The Woman Citizen, June 14, 1924; Keith Lafortune. “Women at the Harvard College Observatory, 1877-1919: ‘Women’s Work,’ The ‘New’ Sociality of Astronomy, and Scientific Labor,” University of Notre Dame, December 2001. Accessed August 19, 2013; Margaret Walton Mayhall. “The Candelabrum” in The Sky. January, 1941; Moira Davison Reynolds. American Women Scientists: 23 Inspiring Biographies, 1900-2000. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1999; “Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming (1857–1911)” on the Harvard University Library Open Collections Program, 2013. Accessed September 3, 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)