The World’s First “Carphone”

Meet the 1920 radio enthusiast who had the foresight to invent the annoying habit of talking on the phone while in the car

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201201251000591920-March-Sandusky-Register-Sandusky-OH-470x251.jpg)

As I noted last week, the term “wireless telephone” in the early 1920s didn’t necessarily mean a device that could both transmit and receive messages. In fact, most radio devices during this time were simply either a transmitter or a receiver. However, some inventors were having a lot of fun tinkering with what was essentially walkie-talkie technology, in that they were developing transceivers — devices that could both transmit and receive radio messages. An article in the March 21, 1920 Sandusky Register in Sandusky, Ohio retold the story of a man in Philadelphia named W. W. Macfarlane who was experimenting with his own “wireless telephone.” With a chauffeur driving him as he sat in the back seat of his moving car he amazed a reporter from The Electrical Experimenter magazine by talking to Mrs. Macfarlane, who sat in their garage 500 yards down the road.

Headline for an article in the March 21, 1920 Sandusky Register (Sandusky, Ohio)

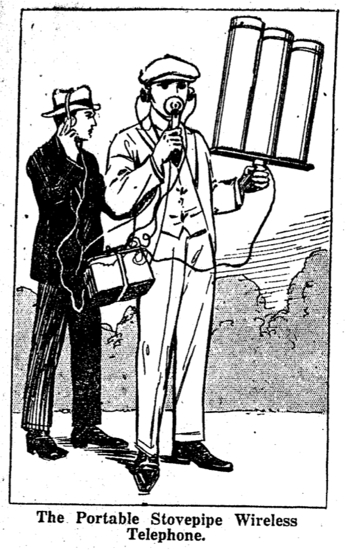

A man with a box slung over his shoulder and holding in one hand three pieces of stove pipe placed side by side on a board climbed into an automobile on East Country Road, Elkins Park, Pa.

As he settled in the machine he picked up a telephone transmitter, set on a short handle, and said:

“We are going to run down the road. Can you hear me?”

Other passengers in the automobile, all wearing telephone receivers, heard a woman’s voice answering: “Yes, perfectly. Where are you?”

By this time the machine was several hundred yards down the road and the voice in the garage was distinctly heard.

This was one of the incidents in the first demonstration of the portable wireless telephone outfit invented by W. W. Macfarlane, of Philadelphia, as described by the Electrical Experimenter.

Mrs. Macfarlane, sitting in the garage back of the Macfarlane home, was talking through the wireless telephone to her husband, seated comfortably in a moving automobile 500 yards away.

The occupants of the car were a chauffeur, a reporter and a photographer. All wore the telephone receivers and could hear everything Mrs Macfarlane was saying. The chauffeur had no other apparatus than the receiver with the usual telephone cord attached to a metal clip to his steering wheel.

Lying beside Mr. Macfarlane was the foot-square box, the only “secret” in the whole demonstration. What is in the box is the inventor’s mystery. This box weighs about twelve pounds. The other machinery used consisted only of the usual telephone transmitter and receivers and the three pieces of stove pipe standing erect on a plain piece of board. This forms the aerial of the apparatus.

The mobile transceiver developed by W. W. Macfarlane in 1920

As the article notes, this story was first reported in an issue of Hugo Gernsback’s magazine The Electrical Experimenter. Gernsback was an important popular figure in the development of radio and in 1909 opened the world’s first store specializing in radios at 69 West Broadway in New York. The reporter from the Experimenter asked Macfarlane if his device, which he said cost about $15 to make (about $160 adjusted for inflation), had any practical uses in the future. Macfarlane instead looks backward and wonders how it might have shaped World War I, which ended less than two years before.

“If this could have been ready for us in the war, think of the value it would have had. A whole regiment equipped with the telephone receivers, with only their rifles as aerials, could advance a mile and each would be instantly in touch with the commanding officer. No runners would be needed. There could be no such thing as a ‘lost battallion.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)