She’s the “avenging angel,” the “ministering angel,” the “lady with the lamp”—the brave woman whose name would become synonymous with selflessness and compassion. Yet as Britain prepares to celebrate Florence Nightingale’s 200th birthday on May 12—with a wreath-laying at Waterloo Place, a special version of the annual Procession of the Lamp at Westminster Abbey, a two-day conference on nursing and global health sponsored by the Florence Nightingale Foundation, and tours of her summer home in Derbyshire—scholars are debating her reputation and accomplishments.

Detractors recently have chipped away at Nightingale’s role as a caregiver, pointing out that she served as a nurse for only three years. Meanwhile, perhaps surprisingly, some British nurses themselves have suggested they are tired of working in her shadow. But researchers are calling attention to her pioneering work as a statistician and as an early advocate for the modern idea that health care is a human right. Mark Bostridge, author of the biography Florence Nightingale, attributes much of the controversy to Nightingale’s defiance of Victorian conventions. “We are very uncomfortable still with an intellectually powerful woman whose primary aim has nothing to do with men or family,” Bostridge told me. “I think misogyny has a lot to do with it.”

To better understand this epic figure, I not only interviewed scholars and searched the archives but went to the place where the crucible of war transformed Nightingale into perhaps the most celebrated woman of her time: Balaklava, a port on the Crimean Peninsula, where a former Russian military officer named Aleksandr Kuts, who served as my guide, summed up Nightingale as we stood on the cliff near the site of the hospital where she toiled. “Florence was a big personality,” he said. “The British officers didn’t want her here, but she was a very insistent lady, and she established her authority. Nobody could stand in her way.”

* * *

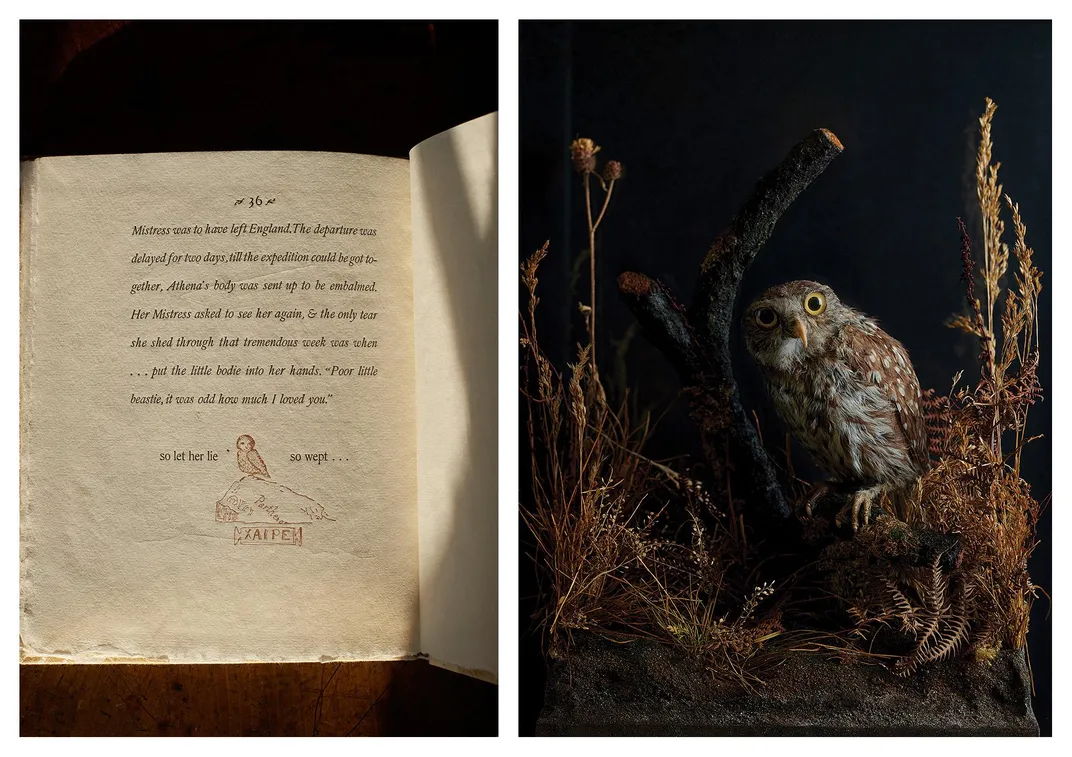

She was named in honor of the Italian city where she was born on May 12, 1820. Her parents had gone there after being married. Her father, William Nightingale, had inherited at age 21 a family fortune amassed from lead smelting and cotton spinning, and lived as a country squire in a manor house called Lea Hurst in Derbyshire, set on 1,300 acres about 140 miles north of London. Tutored by their father in mathematics and the classics, and surrounded by a circle of enlightened aristocrats who campaigned for outlawing the slave trade and other reforms, Florence and her older sister, Parthenope, grew up amid intellectual ferment. But while her sister followed their mother’s example, embracing Victorian convention and domestic life, Florence had greater ambitions.

She “craved for some regular occupation, for something worth doing instead of frittering away time on useless trifles,” she once recalled. At 16, she experienced a religious awakening while at the family’s second home, at Embley Park, in Hampshire, and, convinced that her destiny was to do God’s work, she decided to become a nurse. Her parents—especially her mother—opposed the choice, since nursing in those days was regarded as disreputable, suitable only for lower-class women. Nightingale overcame her parents’ objections. “Both sisters were trapped in a gilded cage growing up,” says Bostridge, “but only Florence broke out of it.”

For years, she divided her time between the comforts of rural England and rigorous training and caregiving. She traveled widely in continental Europe, mastering her profession at the highly regarded Kaiserswerth nursing school in Germany. She served as superintendent of the Institution for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen on Upper Harley Street in London, a hospital for governesses. And she cared for prostitutes during a cholera epidemic in 1853.

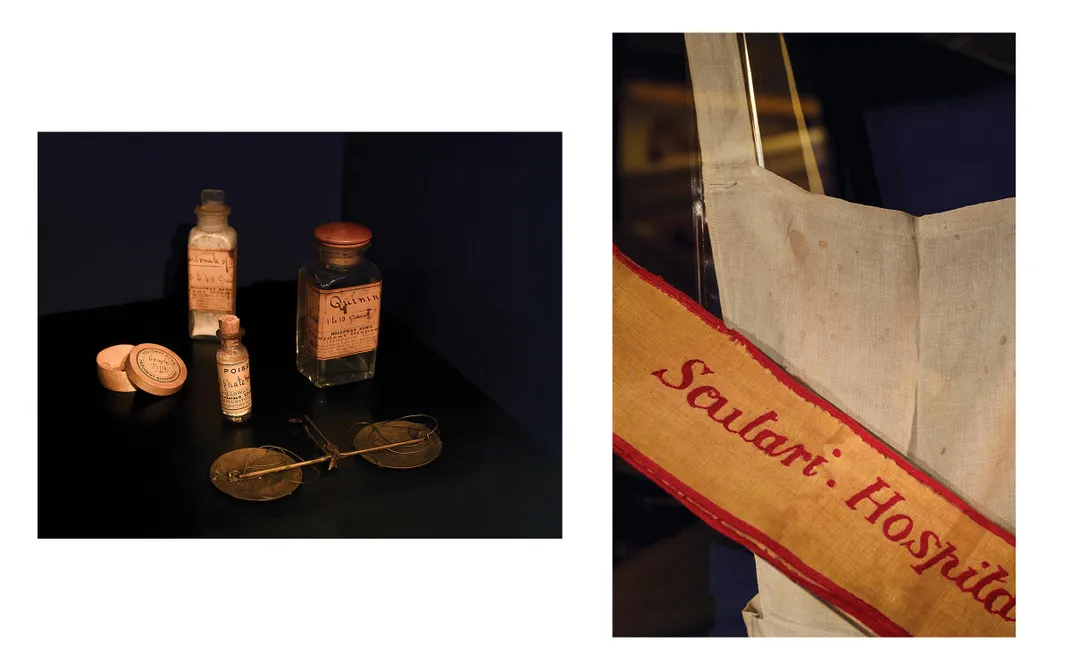

In 1854, British troops invaded the Russian-held Crimean Peninsula in response to aggressive moves by Czar Nicholas I to expand his territory. With the Ottoman and French armies, the British military laid siege to Sevastopol, headquarters of the Russian fleet. Sidney Herbert, the secretary of state for war and a friend of the Nightingales, dispatched Florence to the Barrack Hospital at Scutari, outside Constantinople, where thousands of wounded and sick British troops had ended up, after being transported across the Black Sea aboard filthy ships. Now with 38 nurses under her command, she ministered to troops packed in squalid wards, many of them wracked by frostbite, gangrene, dysentery and cholera. The work would be later romanticized in The Mission of Mercy: Florence Nightingale receiving the wounded at Scutari, a large canvas painted by Jerry Barrett in 1857 that today hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London. (Barrett found Nightingale to be an impatient subject. Their first encounter, reported one of Barrett’s traveling companions, “was a trying one and left a painful impression. She received us just as a merchant would have during business hours.”)

Nightingale rankled commanding officers by going around them. “Miss Nightingale shows an ambitious struggling after power inimical to the true interests of the medical department,” John Hall, the chief British Army medical officer in Crimea, wrote angrily to his superior in London in late 1854 after Nightingale went over his head to order supplies from his stores. Yet she failed initially to stem the suffering. During her first winter at Scutari, 4,077 soldiers died—ten times more from typhus, cholera, typhoid fever and dysentery than from battle wounds. It wasn’t until a newly installed British government dispatched a sanitary commission to Scutari in March 1855 that deaths began to diminish. The commission cleaned out latrines and cesspits, flushed out sewers and removed a dead horse that was polluting the water supply. Within a few months, the mortality rate dropped from 42.7 percent to 2.2 percent.

Today, historians and public health experts debate Nightingale’s role in the turnaround at Scutari. Avenging Angel, a controversial 1998 biography by Hugh Small, contends that Scutari had the highest death rates of any hospital in the Crimean theater, that Nightingale didn’t grasp the role of sanitation in disease prevention until many thousands had died—the author maintains that she focused instead on giving troops warm clothing and hearty food—and that “repressed guilt” over her failures caused her to have a nervous breakdown, which, he argues, turned her into an invalid for long stretches throughout the rest of her life. The British news media picked up Small’s claims—“Nightingale’s Nursing Helped ‘Kill’ Soldiers,” a Sunday Times headline declared in 2001.

But Lynn McDonald, a professor emerita at the University of Guelph near Toronto and a leading Nightingale scholar, disputes Small’s claims. All Crimean War hospitals were ghastly, she insists, and the statistics suggest that at least two had higher death rates than Scutari. McDonald also makes a persuasive case that Nightingale believed the blame for Scutari’s dreadful state lay elsewhere. In her letters, she pointed repeatedly at military doctors and administrators, chastising them for a host of “murderous” errors including sending cholera cases to overcrowded wards and delaying having the hospital “drained and ventilated.” The sanitary commission’s investigation confirmed Nightingale’s suspicions about the links between filth and disease, McDonald contends, and she became determined never to let those conditions occur again. “That is the foundation of all she does in public health for the rest of her life,” McDonald says.

* * *

The Crimean War is largely forgotten now, but its impact was momentous. It killed 900,000 combatants; introduced artillery and modern war correspondents to conflict zones; strengthened the British Empire; weakened Russia; and cast Crimea as a pawn among the great powers. To reach Crimea, I had driven two hours south from the Ukrainian city of Kherson to one of the world’s tensest borders, where I underwent a three-hour interrogation by the FSB, the successor to the KGB. Besides questioning me about my background and intentions, the agents wanted to know how I felt about Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and even about President Trump’s decision to pull U.S. forces out of Syria. Just as it was a century and a half ago, Crimea has become a geopolitical hotbed, pitting an expansionist Russia against much of the world.

In Balaklava, a fishing port, the rhythmic crash of waves against a sea wall resounded through the early morning air as I hiked up a goat trail. The ruins of two circular stone towers built by Genoese traders in the 14th century loomed on the hilltop a few hundred feet above me.

The rugged, boulder-strewn hills presented as treacherous an ascent as they did 165 years ago, when 34-year-old Nightingale would climb from the harbor to the Castle Hospital, a collection of huts and barracks on a flat patch of ground overlooking the Black Sea. She had sailed from Scutari across the Black Sea in May 1855 to inspect medical facilities near the front lines. “You are stepping on the same stones that Florence walked on,” says Aleksandr Kuts, my guide.

After an arduous half-hour, Kuts and I arrive at the plateau where the Castle Hospital once stood. There’s no physical trace of it now, but Nightingale’s letters and the accounts of colleagues who served beside her have kept the place alive in literature—and attest to her physical bravery.

At the Castle Hospital, Nightingale drilled borehole wells to improve the water supply and insulated huts with felt to protect wounded soldiers against the winter cold. Nightingale did indeed try to improve their food; she made sure that the soldiers regularly received meat, not just gristle and bone, along with fresh bread, which she had shipped in daily from Constantinople. She traveled constantly—by carriage, on horseback and on foot—with artillery fire echoing in the background, to inspect other hospitals in the hills that surrounded Balaklava. She even visited the trenches outside Sevastopol, where she was moved by the sight of the troops “mustering & forming at sundown,” she wrote, and plucked a Minié bullet from ground “ploughed with shot & shell” to send to her sister in England as a souvenir. Throughout her sojourn, she faced the resentment of officers and bureaucrats who regarded her as an interloper. “There is not an official who would not burn me like Joan of Arc if he could,” Nightingale wrote from Crimea, “but they know that the War Office cannot turn me out because the country is with me.”

Walking across the windswept plateau overlooking the Black Sea, I tried to imagine Nightingale waking in her cottage on these grounds to face another day caring for the sick and battling bureaucratic inertia in a war zone far from home. On her first interlude here, Nightingale fell ill with a malady that the British troops called “Crimean Fever,” later identified as almost certainly spondylitis, an inflammation of the vertebrae that would leave her in pain and bedridden for much of her life. Despite her illness, she was determined to work until the last British troops had gone home, and she returned twice during the war—once in October 1855, after the fall of Sevastopol, when she stayed for a little more than two months, and again amid the bitter winter of March 1856, and remained until July. “I have never been off my horse until 9 or 10 o’clock at night, except when it was too dark to walk home over these crags even with a lantern,” she wrote to Sidney Herbert in April 1856. “During the greater part of the day I have been without food, except a little brandy and water (you see I am taking to drinking like my comrades in the army).”

* * *

Nightingale sailed for England from Constantinople on July 28, 1856, four months after the signing of the Treaty of Paris that ended the Crimean War. She had spent nearly two years in the conflict zone, including seven months on the Crimean Peninsula. Vivid dispatches filed from Scutari by correspondent Sir William Howard Russell, as well as a front-page engraving in the Illustrated London News showing Nightingale making her rounds with her lamp, had established her in the public eye as a selfless and heroic figure. By the time she returned home, she was the most famous woman in England after Queen Victoria.

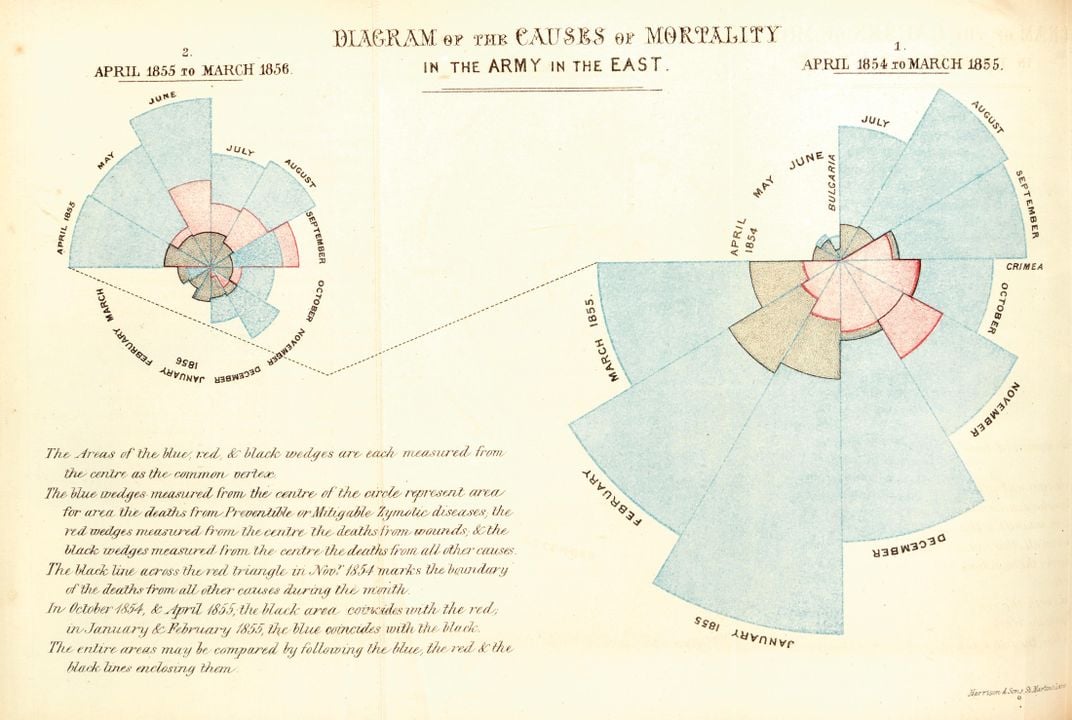

Still, Nightingale had little interest in her celebrity. With William Farr, a mentor and noted government statistician, she gathered data from military hospitals in Constantinople that verified what she had long suspected: Nearly seven times as many British soldiers had died of disease in the Crimean War than in combat, and the deaths dropped dramatically once hospitals at the front were cleaned up. She also collated data from military hospitals in Great Britain, which revealed that these facilities were so poorly ventilated, filthy and overcrowded that their mortality rates far exceeded those at Scutari following the changes implemented by the Sanitary Commission. “Our soldiers enlist to death in the barracks,” she wrote. In “Notes Affecting the Health, Efficiency, and Hospital Administration of the British Army,” published in 1858, she and Farr displayed their findings in graphic illustrations known as coxcombs—circular designs divided into 12 sectors, each one representing a month—that clearly laid out the direct relationship between improved sanitation and plummeting death rates. These innovative diagrams, she said, were “designed ‘to affect thro’ the Eyes what we may fail to convey to the brains of the public through their word-proof ears.”

Swayed by her presentations, the military improved hospitals throughout Great Britain, and Parliament voted to finance the first comprehensive sewage system for London. “She was a one-woman pressure group and think tank,” says David Spiegelhalter, a University of Cambridge statistician and author.

Though often bedridden in London hotels and rented flats over the years, Nightingale continued to gather data on every aspect of medical care. She sent questionnaires to hospital administrators, collected and analyzed results, wrote reports, established investigative commissions. She produced findings on the proportion of recoveries and deaths from various diseases, average disease recovery times according to patients’ age and gender, and high rates of communicable disease such as septicemia among hospital workers. Nightingale came to believe, says Spiegelhalter, that “using statistics to understand how the world worked was to understand the mind of God.” In 1858, she became the first woman to be made a fellow of the Royal Statistical Society.

Nightingale founded the country’s first nurses’ training school, at St. Thomas Hospital in London, across the Thames from the Houses of Parliament, in 1860. She viewed the project as a moral crusade intended “to promote the honest employment, the decent maintenance and provision, to protect and restrain, to elevate in purifying...a number...of poor and virtuous women,” she wrote at the time.

Concern for society’s disadvantaged shaped her initiatives for the rest of her life. She criticized the Poor Laws, prodding Parliament to improve the workhouses—shelters for the indigent—by establishing separate wards for the sick and the infirm, introducing trained nurses and forming oversight boards. “She had a nonjudgmental, nonmoralistic view of the poor, which was radical at the time,” says Spiegelhalter. She wrote prolifically about crime, labor and the social causes of madness, and originated the concept that soldiers injured in war should be considered “neutral” and that they and their caregivers should be accorded protection on the battlefield. That ethic would become central to the International Committee of the Red Cross, founded in Geneva in 1863.

Nightingale’s personal life was complicated, and fuels speculation to this day. As a young woman, she had considered several marriage proposals, including one from Richard Monckton Milnes, an aristocratic politician and poet who was a frequent visitor at Lea Hurst, the Nightingale family estate. Charmed by him but also ambivalent about the compromises she would have to make as a married woman, Nightingale hesitated until it was too late. “Her disappointment when she heard he was getting married to someone else because she had waited so long was considerable,” says Bostridge. “But you have a choice as a Victorian woman. If you want to go out in the world and do something, then marriage and children are not really an option.” She was, in any case, a driven figure. “She has little or none of what is called charity or philanthropy,” her sister, Parthenope, wrote. “She is ambitious—very, and would like...to regenerate the world.”

Elizabeth Gaskell, the novelist and family friend who visited Lea Hurst in 1854, observed that Nightingale appeared far more interested in humanity in general than individuals. Bostridge is sympathetic. “It’s understandable when you’re trying to reform the world in so many ways, to be centered on the universal idea of mankind rather than individuals,” he says.

Some of Nightingale’s public health campaigns went on for decades. In the 1860s, she joined the social reformer Harriet Martineau in an attempt to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts, which authorized the arrest and compulsory inspection for venereal disease of prostitutes around naval bases and garrison towns. Nightingale believed that the women’s male clientele were as responsible as the women in spreading disease, and she compiled statistical charts that showed the forced inspections were having no effect at bringing down the infection rates. The law was at last overturned in 1886.

Yet few members of the British public were aware of Nightingale’s role in the campaign, or in any of the other reforms that changed the face of British society. She had expressed her discomfort with fame as early as 1850, when she wrote in her diary that God had called upon her and asked, “Would I do good for Him, for Him alone, without the reputation?” After her Crimean War glory, “much of the British public thought she had died,” says Bostridge. But in 1907, Nightingale became the first woman to receive the Order of Merit, a highly prestigious award instituted by Edward VII. The ceremony resulted in a surge of renewed interest in the nearly forgotten nurse and social reformer. She died three years later, at the age of 90.

* * *

More than a century after her death, it may seem strange that out of all those who have stepped up to criticize Nightingale, perhaps the most vociferous have been some nurses in the British public services union UNISON. Some regard her as a privileged elitist who favored a strictly hierarchical approach to nursing, opposed higher education for nurses and wanted them to remain devout, chaste and obedient. UNISON declared in 1999 that Nightingale had “held the nursing profession back too long” and represented its most “negative and the backward elements.” The union demanded that International Nurses Day, celebrated on Nightingale’s birthday, be moved to a different date. Nightingale’s defenders fired back, insisting that the criticism was misplaced, and the attempt failed.

Meanwhile, a group in London recently campaigned to recognize the contributions of a different woman in the Crimean War: Mary Seacole, a black Jamaican entrepreneur who ran a restaurant for officers in Balaklava during the war and sometimes prepared medicines and conducted minor surgery on troops. Champions of Seacole insisted that she deserved the same kind of recognition that Nightingale has enjoyed, and, after years of lobbying, succeeded in erecting a statue of Seacole at St. Thomas Hospital. The monument contains the words of one of Seacole’s admirers, Times correspondent Sir William Howard Russell: “I trust that England will not forget one who nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them, and who performed the last offices for some of her illustrious dead.”

The tribute outraged devotees of Nightingale, who insist that Seacole deserves no such recognition. “British nurses fell for the Seacole line,” says Lynn McDonald, who wrote a biography entitled Mary Seacole: The Making of the Myth that minimized her role as a nurse. McDonald claims that Seacole even harmed some troops by treating dysentery with lead and mercury. “She was feisty, independent and set up her own business,” McDonald says. “But what she mainly did was provide meals and wine to officers in her restaurant and takeaway. I’d be happy to have the statue disappear.”

The controversy would probably have vexed Nightingale, who had a pleasant encounter with Seacole in 1856, when the Jamaican stopped in Scutari on the way to Balaklava. Though Nightingale would later express misgivings about reports of hard drinking at Seacole’s restaurant, she would mostly have warm words for her. “I hear she has done a great deal of good for the poor soldiers,” she would say, even contributing to a fund for Seacole after she was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1857. Seacole returned the compliment, praising Nightingale in her autobiography with words that would make a fitting epitaph: “That Englishwoman whose name shall never die but sound like music on the lips of men until the end of doom.”

* * *

Lea Hurst is perched on a hill overlooking rolling lawns, groves of birch trees and the Derwent River. The 17th-century estate retains a pastoral, cloistered feeling, with gabled windows, stone chimneys jutting from the roof and deep red Virginia creeper climbing the handsome gray stone facade. Many years ago the Nightingale family property was eventually converted into a nursing home, but Peter Kay, a former banker who had worked in Singapore and Manila, purchased it four years ago. He lives here with his wife and four children and has been turning the house into a kind of Florence Nightingale museum.

Kay and his wife renovated the once-crumbling mansion and, with the help of an antiquarian friend in London, are filling it with period pieces and Nightingale memorabilia. A pocket-size prayer book signed by Nightingale sits on a sideboard, near a wooden sedan chair that a British officer seized from a Russian fort in Sevastopol.

Kay leads me through the green-painted library, where William Nightingale tutored his daughters. A nook with bay windows designed and built by Florence, an amateur architect, looks out over handsome fall foliage. Kay is now seeking to acquire the carriage that Nightingale rode in during her inspection tours through the hills of Crimea. It’s currently on display at the former home of Parthenope and her husband, Harry Verney, administered by the National Trust.

Kay and I walk upstairs to the bedroom wing, which he has recently made available to guests. I put down my suitcase in Nightingale’s bedchamber, with a balustraded balcony looking out on the Derwent River. “She had the option of having a society life in a nice big house, with a staff of servants. It was all mapped out for her,” says Kay, a self-taught Nightingale authority. “But she pushed against it and devoted herself to a higher calling. And she would single-mindedly break down barriers.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/b7/c1b7744d-970d-440c-b210-19ace7eca747/opener-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/c8/20c89fb0-dd7b-4938-a99c-a9ae80987d7a/opener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)