The Writer Who Built the World’s First Engine-Powered Submarine

Narcis Monturiol loved the ocean’s corals so much, that he built a machine so he could better enjoy them

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ictineo_plan-631.jpg)

A man cannot one day just decide to build a submarine, much less the first powered submarine, much less if that man is a writer. Yet that is just what Narcis Monturiol did.

As a young firebrand of the mid-19th century, Monturiol flirted with inflammatory subjects including feminism and Communism, placing him under the watchful eye of an oppressive regime. When he fled to Cadaqués, an isolated town on the Mediterranean coast of Spain, he found a peaceful fishing village where he could expand on his ideas of a Utopian world. It turned out that Cadaqués would also be the inspiration for his biggest idea.

In Cadaqués, the few locals mostly fished from the shore or from boats. Others dove for coral and returned with a magical diversity of things—fish, crabs, snails and, of course, great and wondrous corals, sold as decoration for local homes. Monturiol became transfixed by these treasures, seeing them as baubles befitting a Utopia. He admired the coral divers for their quest—a quest for discovery in an the unknown realm beneath the waters that he called “the new continent”—but was troubled by an accident in 1857 that left one diver dead by drowning.

He was so affected by the sight that he wanted to do something to make the life of coral divers easier. As Robert Roberts, one of Monturiol’s later collaborators put it, “The harvesting of valuable coral and the relatively scarce fruits born to those that dedicate their livelihood to this miserable industry…incited Narcís Monturiol.”

Munturiol had always been a dreamer. He was born in 1819 in Figueres, a town in Catalonia, the region that would later give birth to eminent artists including Salvador Dali, Antony Gaudi, Pablo Picasso and Joan Miro.

Monturiol’s father was a cooper, designing and building barrels for the wine industry. Monturiol could have continued in his father’s footsteps but instead chose to become a writer and socialist revolutionary. At an early age, Monturiol began to write about feminism, pacifism, Communism and a new future for Catalonia, all of which are the sort of things that make dictatorships, such as that of then Spanish statesman Ramón María Narváez, uncomfortable. Persecuted for his beliefs, Monturiol fled to France for a while before returning to Spain. When his writings got in trouble again, this time in France, he came to Cadaqués, the coastal town just a few miles from Figueres.

In 1857, with visions of the new continent in his mind, his Utopia that he and his friends would create through writing and art, Monturiol went home to Figueres to begin his project. This all sounds ridiculous and quixotic, because it is.

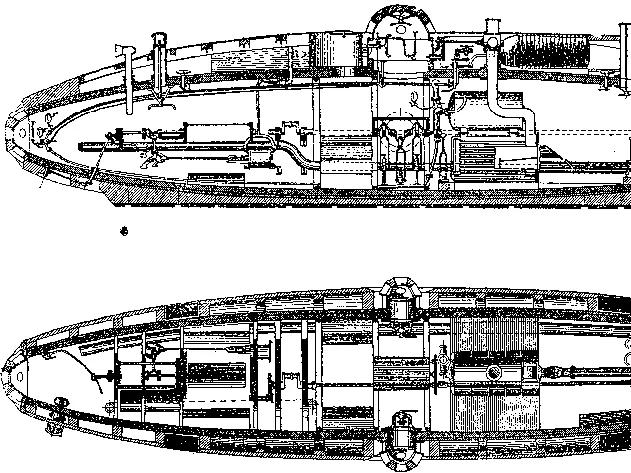

Just how Monturiol came up with his specific plans is unclear. Perhaps thanks to his father’s influence, though Monturiol also hired a master builder of ships and a designer to help, the submarine came to look a bit like a giant wine barrel, tapered at both ends. It was at once simple and sophisticated.

Submarine technology wasn’t new to Monturiol or his contemporaries: historical mentions of “diving boats” can be traced to the time of Alexander the Great. The first real submarine – a boat capable of navigating underwater – was built by Cornelius Drebbel, a Dutch inventor who served in the court of England’s King James I during the Renaissance. Drebbel’s crafts were manually powered, requiring 12 oarsmen to row the underwater vessel whose submersion was controlled by the inflating – or deflating – of rope-tied pig’s bladders placed under each oarsmen’s seat. Into the 18th and 19th centuries, the Russians perfected Drebbel’s vision, creating the first prototype for a weaponized submarine under the patronage of Czar Peter I in June of 1720. Submarine technology continued to pique the interest of innovators – especially in Russia and Germany – but economic and scientific constraints hindered the expansion of submarine technology into the 19th century.

By the summer of 1859, just two years after the drowning, his dream was built. The submarine was 23 feet long and equipped with appendages for gathering coral and whatever else could be found in the great and unknown abyss. Monturiol was eager to test the submarine and took it for a trial with a crew of two other men, including the boat builder, in Barcelona’s harbor—even he was not bold enough to attempt a maiden voyage in in Cadaqués’ stormy bay. The submarine, named Ictíneo, a word Monturiol created out of the Greek words for fish and boat, was double-hulled, with each hull made of olive wood staves sheathed in copper. It moved thanks to Monturiol’s own foot power via two pedals, or at least that is how he hoped it would move.

Monturiol untied the mooring rope as a small crowd looked on, climbed in, waved and closed the hatch. The submarine began to move under human power and as it did, it disappeared into the water. It worked! Monturiol eventually completed more than 50 dives and established that the submarine was capable of diving to 60 feet and staying submerged for several hours. The submarine was able to dive deeper and for more hours than any submarine that had ever been built.

To Monturiol, the experience was at once tremendous and terrifying. As he would later write: “The silence that accompanies the dive…; the gradual absence of sunlight; the great mass of water, which sight pierces with difficulty; the pallor that light gives to the faces; the lessening movement in the Ictíneo; the fish that pass before the portholes—all this contributes to the excitement of the imaginative faculties."

For a while, Monturiol enjoyed the excitement and tried to drum up interest among investors for the production of more-advanced submarines. Catalonians pledged money at concerts, theatre performances, and other gatherings were held, town to town, to garner funds and support for his endeavors. Then, one day in 1862, a freighter drilled straight into the sub, which was docked in Barcelona’s Harbor, and crushed it. No one was harmed, and yet the dream splintered.

Monturiol was distraught. The Ictineo had taken years of his life. Now he had no choice. He would have to build the Ictineo II, an even larger submarine.

In 1867, the Ictineo II launched successfully. Monturiol descended to 98 feet and yet, to him, the endeavor still seemed clumsy. It was hard to power a submarine with nothing but one’s legs. Monturiol opted to develop a steam engine to be used inside the submarine. The steam engine, like the submarine, was not a new invention. It had been around for almost two centuries: Thomas Newcomen first patented the idea in 1705, and James Watt made innumerable improvements in 1769. In a standard steam engine, hot air is forced into a chamber with a piston, whose movement produces the power to motor practically anything, such as a submarine. For Monturiol, however, he couldn’t simply apply the technology of a standard steam engine because it would use up all of the valuable oxygen in the sub. The standard steam engine relies on combustion, using oxygen and another fuel substance (usually coal or fire) to produce the heat needed to create steam. This wouldn’t work. Instead, he used a steam engine run by a chemical reaction between potassium chlorate, zinc, and manganese dioxide that produced both heat and oxygen. It worked, making the Ictineo II the first submarine to use a combustion engine of any kind. No one would replicate his feat for more than 70 years.

Others tried to copy the concept of an engine-propelled submarine, but many failed to replicate the anaerobic engine Monturiol had created. It wasn’t until the 1940s that the German Navy created a submarine that ran on hydrogen peroxide, known as the Walter Turbine. In the modern era, the most common anaerobic form of submarine propulsion comes from nuclear power, which allows submarines to use nuclear reactions to generate heat. Since this process can occur without any oxygen, nuclear submarines can travel submerged for extended periods of time – for several months, if need be.

When Monturiol began constructing his submarine, the United States was entangled in the Civil War. Both sides in the conflict used submarine technology, though their vessels were rudimentary and often sank during missions. When Monturiol read about the Civil War – and attempts to use submarine technology in the conflict – he wrote to Gideon Welles, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy, to offer his expertise and designs to the North. Unfortunately, by the time Welles responded to Monturiol’s solicitation, the Civil War had ended.

The submarine was an incredible innovation, but the timing was wrong. He could not sell the submarine and for whatever reason he did not choose to explore on his own. He desperately needed and wanted more funding to feed himself and, of course, produce more submarines and, at this point, would do nearly anything for it. He even installed a cannon on the submarine to interest the military—either that of Spain or, as he later tried, the United States (so much for pacifism)—all to no avail. In 1868, he sold his dream submarine for scrap. Its windows went into Spanish bathrooms and its engine—the first submarine engine in the world—became part of a device used to grind wheat. The grand machinery of his imagination would be used to make food, each bite bearing, one supposes, some taste of Monturiol’s dreams.

Monturiol died broke, and his submarines do not seem to have directly inspired any others. Yet, in Catalonia he has come to have a kind of understated fame. He was Dali before Dali, Catalonia’s first visionary artist, who worked with the tools of engineering rather than painting. The most concrete testimonies are a replica of his submarine in Barcelona harbor and a sculpture of him in the square in Figueres. In the sculpture, Monturiol is surrounded by muses. Even though the muses are naked, the statue seems to go largely unnoticed, overshadowed in the town by the more prominent legacy of Dali. But maybe the real testimony to Monturiol is that his spirit seems to have continued just beneath the surface in Catalonia. People know his story and every so often, his spirit seems to rise up like a periscope through which the visionaries—be they Dali, Picasso, Gaudi, Miro or anyone else—can see the world as he saw it, composed of nothing but dreams.