Turn-of-the-Century Kid’s Books Taught Wealthy, White Boys the Virtues of Playing Football

A founder of the NCAA, Walter Camp thought that sport was the cure for the social anxiety facing parents in America’s upper class

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/2c/042caa69-9b76-4c5a-a8e1-87bc0f2aaa55/d11h4d.jpg)

More than anyone, Walter Camp helped popularize the game of football in the United States during the late 1800s and early 1900s. In addition to playing for and coaching Yale’s powerhouse team, Camp played a prominent role in establishing the rules for modern football and launching the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). He promoted the sport for decades, writing and lecturing on football’s health benefits into the 1920s, and inaugurated the tradition of naming an annual All-American team of the nation’s best college players. His influence lasted long enough that in 1967, more than four decades after his death, the NCAA named its Player of the Year Award after him.

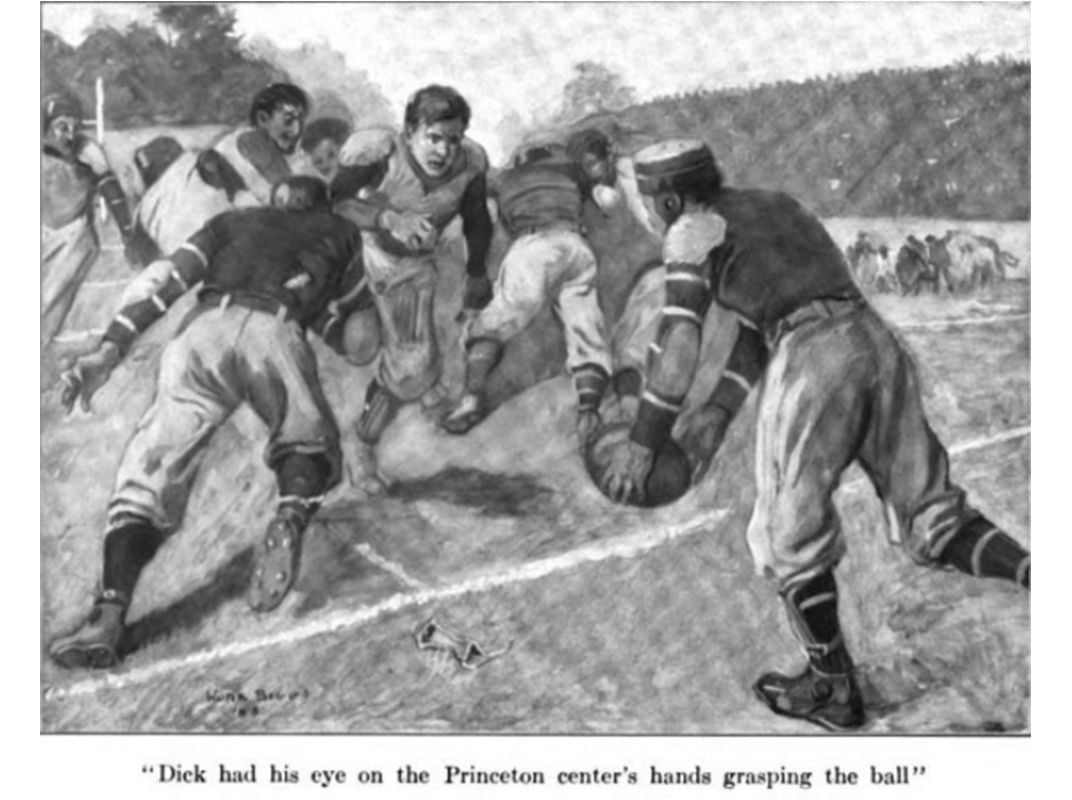

Forgotten among these accomplishments, however, are the series of novels for boys that Camp published between 1909 and 1917. These books, popular in their time, illuminate Camp’s thinking on why football (and sports in general) was crucial to the physical and mental development of the nation’s elite young men. When considered in historical context, the novels also reveal the flip side of his argument. In the half-century after the Civil War, series books were marketed to the children, and particularly the boys, of wealthy, white Americans, as was organized sport. The two pastimes – reading and football—fuse together in Camp’s novels, illuminating how integral social anxieties about these boys were to the emergence of football as mass entertainment.

The world that Camp presents in his novels is one of whiteness and wealth. When Dick Goddard, the protagonist of the series’ first book The Substitute, describes the “colored chap who played tackle on our team up at school” as “white enough,” “a good player,” and “a good deal more decent than some men I know,” he reveals not only the singularity of this nameless teammate, but also the passive discrimination of the series. The novels feature almost no women, no people of color, and no immigrants (at a time when the percentage of immigrants within the U.S. population was at a historic peak). Less-than-wealthy Americans are represented only by the character Thomas Hall, an orphan putting himself through Yale after an anticipated inheritance from his grandfather failed to materialize.

This perspective was common in children’s series books of the era. Around the turn of the century, these books surged in popularity by giving young characters both more exciting adventures and more freedom to act independently than did other genres of children’s literature. American boys in these series fought in the Spanish-American and Russo-Japanese Wars. Characters like Tom Swift and the Rover Boys experimented with modern technology like motorcycles and submarines while traveling the world without supervision (later series such as the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew added mysteries that the young protagonists solved free of – or sometimes despite-- adult interference).

One limitation of these freedoms was that the protagonists had to be white and from prosperous families; only villains and sidekicks could display any degree of ethnic, racial or class diversity. This uniformity, along with their price of a dollar or more per book at a time when dime and half-dime novels remained common, reflects the intention of publishers to appeal to a wealthy, white, Protestant audience.

Camp’s main characters are promising but flawed young men. The protagonist of Old Ryerson, for example, is a large, slow-moving high schooler who excels at his studies but struggles with social and physical tasks, causing family members and classmates to discount him as a “dig” and a “grind” incapable of effective leadership. Danny Phipps, the protagonist of three books, is naturally charismatic and athletic but fails to control his temper and defer to coaches and other authority figures. Even Dick Goddard, who earns praise for being “steady as a rock,” is immature and has difficulty developing strategies for self-improvement.

These storylines exemplify the broader concerns held among educated and prosperous white Americans of the time about the likelihood that their next generation would be able to retain status atop American society. Confronted by declining white birth rates and rising immigrant and (in the North) African-American populations, these adults worried that extended schooling, urban living and the diminution of physical labor were making their children physically and mentally weak at a time when their control over the nation’s future seemed less secure than ever before. The most alarmist of these critics raised fears that white Americans were heading toward “race suicide.”

Camp and other successful men offered sports, particularly when played within the protective environment of preparatory schools and universities, as one prescription for these problems. The Substitute begins with a paragon of this approach: Fairfax, an “old graduate” of Dick Goddard’s school and currently the captain of Yale’s football team. Fairfax gives Dick and his classmates a long speech encapsulating Camp’s philosophy: work hard, play fair but play to win, and strive to be part of something larger than yourself. Throughout the series, Dick and his friends follow Fairfax’s advice and example, and gradually their participation in sports—baseball, crew, wrestling, and most of all football – instills these virtues into their inconstant but improving young minds.

This faith in the developmental value of football was crucial to the game’s survival amidst an existential crisis of its own. During the first decade of the 1900s, a wave of dozens of deaths and even more crippling injuries to high school and college football players led educators and political leaders, including President Theodore Roosevelt, to call for tougher regulation and in some cases even abolition of the game. These ongoing debates over the game’s safety culminated with several prominent schools (including Columbia, Duke, Northwestern and Georgetown) shutting down their teams and with the implementation of fundamental rule changes (including the legalization of the forward pass) intended to mollify football’s many critics. The game’s perceived role in molding the characters of the nation’s elite young men was not the only reason football survived this moment—the financial benefits the game provided for both universities and the press also helped – but the beliefs of advocates, including Roosevelt who promoted the benefits of “rough, manly sports,” certainly aided the cause.

The centrality of wealthy white boys these now-familiar debates over football’s safety may seem peculiar now when it’s poor and minority young men who predominate in the game. Camp’s books, though, exemplify more than just this inversion. They also reveal that football, like series books and other leisure products and activities, thrived during his time as part of a reconstruction of American childhood. Parents’ focus shifted away from sheltering children from the outside world and toward helping young people develop skills that would enable them to prosper in a rapidly changing culture. It was under these transitional circumstances that football gained legitimacy, and only after this acceptance was the game able to expand into the mass-market entertainment that it is today.