These Photo Albums Offer a Rare Glimpse of 19th-Century Boston’s Black Community

Thanks to the new acquisition, scholars at the Athenaeum library are connecting the dots of the city’s social network of abolitionists

:focal(392x205:393x206)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/4e/e14ebe70-e948-44d7-a533-2a88dfbedda9/letterboxed.jpg)

With a quiet, unflinching confidence, Virginia L. Molyneaux Hewlett Douglass posed for the photographer, one slender hand rustling the pleats of her fine silk dress. Although portraits were trendy and accessible in the 1860s when hers was shot, hand-colored photographs were a luxury, and this one is saturated with shades of emerald and lilac, underlining Virginia’s wealth and high social standing as the wife of Frederick Douglass, Jr., son of the celebrated abolitionist. Her name is handwritten above the portrait in flowery cursive as Mrs. Frederick Douglas, pasted into one of two recently discovered albums that have the potential to change much of what we know of the network of African-Americans centered around the steep north slope of Boston’s Beacon Hill in the 1860s and beyond.

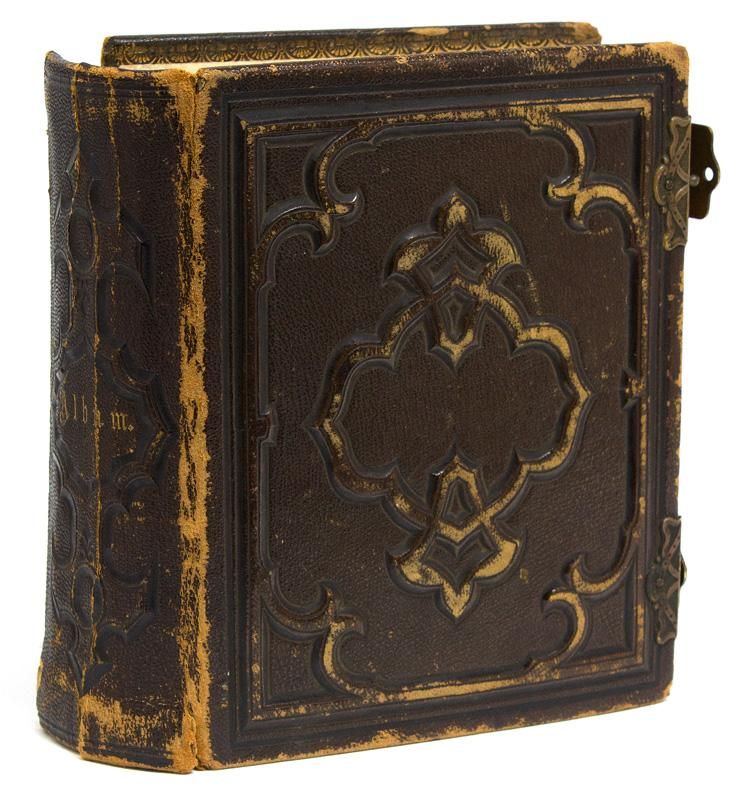

Last fall, the Boston Athenaeum—one of the nation’s oldest independent libraries—quietly acquired the two leather-bound photo albums believed to have been compiled in the 1860s by Harriet Bell Hayden, who fled slavery in the South to become a deeply respected member of the city’s African-American community.

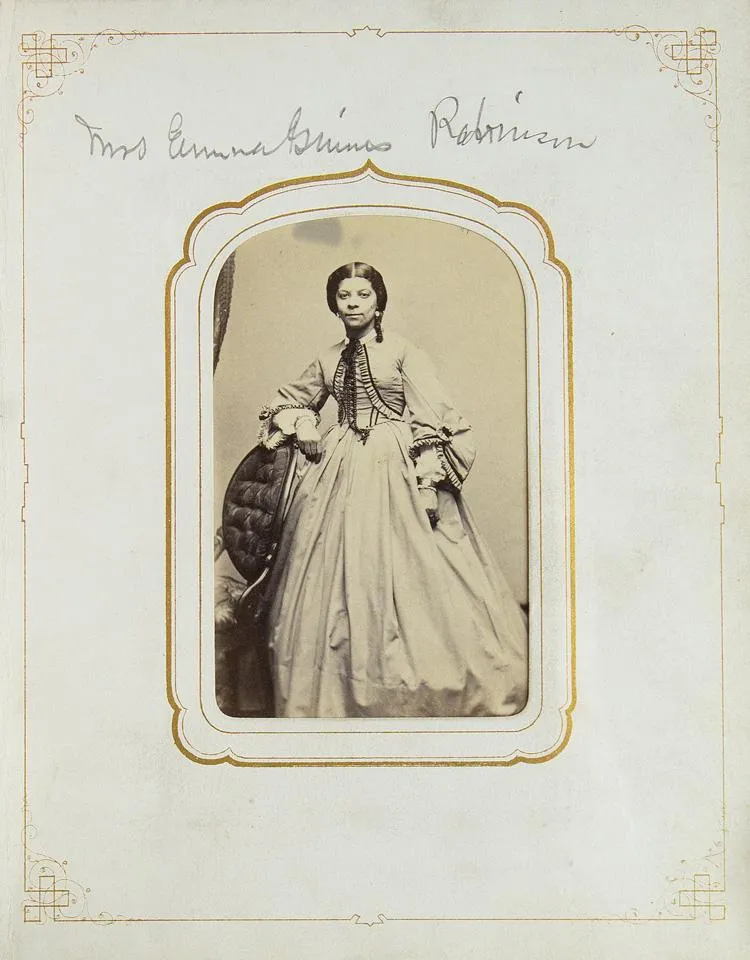

Inside the albums’ delicate brass clasps lie a treasure trove of 87 portraits, a veritable “Who’s Who” of 19th-century Black Boston dressed to the nines in Victorian finery. The images bring to life politicians, military officers, literary figures, financiers, abolitionists and children, formally posed in opulent studio settings and gazing with great dignity directly at the camera.

Procured from a dealer who had acquired the albums at auction, the two albums were tenderly preserved by a New England family for generations, says John Buchtel, the Athenaeum’s curator of rare books. The albums provide the opportunity to piece together details of a remarkably courageous life all too often reduced to having simply been wed to an important man. “We don’t know a lot about Harriet Hayden. Her name is always linked to [her husband, Lewis],” concedes Jocelyn Gould, a guide with the National Parks Boston who gives lectures at the African Meeting House, the church that formed the socio-political cornerstone of the Haydens’ community.

As for Lewis, we know that it was his experiences as an enslaved laborer, including having his first wife and son sold away, that built a fiery drive to not only escape slavery but bring others out of it as well. The Haydens and their son escaped from bondage in 1844, arriving in Canada with the help of two abolitionists from Oberlin College. They ultimately resettled in Boston in 1846 out of a moral compulsion to further the abolitionist cause.

“By the 1860s, you have a vibrant community here who are Boston-born, but also many who have heard about this community and decided to resettle here,” says Gould. “Some of those people are free and others are fugitive slaves, but because you have religion, school, and community life established already, there's a safety net in place to make people feel comfortable staying despite the ever-present threat of danger of being sent back into slavery.” She also cites an 1860 census that lists Beacon Hill as having the largest population of Black Bostonians, though it’s hard to get an accurate number as the neighborhood was also shared by lower-income white residents.

Lewis, meanwhile, taught himself to read and write, then campaigned on behalf of the American Anti-Slavery Society and joined the Boston Vigilance Committee. He was ultimately elected in 1873 as a representative to the Massachusetts State legislature, and the Haydens became a Beacon Hill power couple of their day.

They also risked their own lives—and freedom—to turn their home at 66 Phillips Street into a stop on the Underground Railroad. In 1853, Harriet Beecher Stowe visited the home to conduct research for Uncle Tom’s Cabin and counted 13 fugitive slaves in residence.

Although Lewis is always mentioned before Harriet, largely in part to his political successes, she was managing the home, hosting fugitive slaves, political figures, and white abolitionist financiers alike. An 1894 obituary (published in The Cleveland Gazette a year after her death) names Harriet as “a favorite with the young ladies of Boston,” suggesting that her social reach transcended race. Her final act—astonishing for a woman who never had access to formal education herself—was to endow The Lewis and Harriet Hayden Scholarship Fund for the education of African-American physicians at Harvard Medical School.

* * *

Most images in the albums are in cartes de visite format, approximately three-by-four-inch black-and-white portraits mounted on sturdy cardboard. First patented in 1854 in France and popular in the United States by 1860, the process was more accessible than painted portraiture, which was an indulgence only for the elite, and daguerreotype photography, which was more expensive and only yielded one print at a time with copies available only to those of means. The rampant popularization of the cartes de visite offered everyday Americans the chance to visit local photography studios and sit for affordable, commercial portraits that were cheaply reproduced to hand out to family and friends, sent by post, or commissioned as a keepsake before a soldier left for battle.

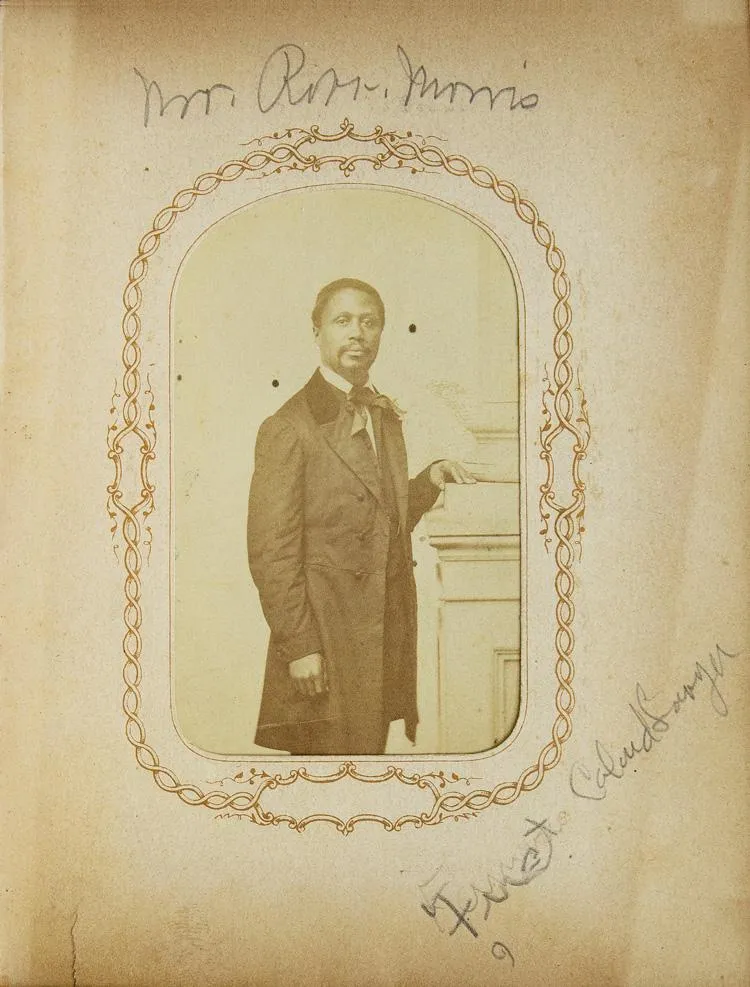

The albums are formally inscribed as gifts to Harriet, one in 1863 from Robert Morris, the first black lawyer to win a lawsuit in the U.S. and a gutsy abolitionist who famously defended Shadrach Minkins, a fugitive who escaped from Virginia and found work in Boston, only to be captured and tried under the contentious Fugitive Slave Act. During the trial, Lewis Hayden led a band of abolitionists in storming the courtroom and forcibly pushed aside the marshals, carrying off Minkins and hiding him in a Beacon Hill attic until safe passage to Canada was arranged.

Hayden, Morris, and others involved were subsequently indicted, tried and acquitted. “It makes sense, that as a pillar of the community, Morris would have known and been close to [the Haydens],” says Gould. The other album was presented with an inscription by S.Y. Birmingham M.D., and although his wife and children appear in the album, the Athenaeum is still working to uncover information about the family and their relationship to the Haydens.

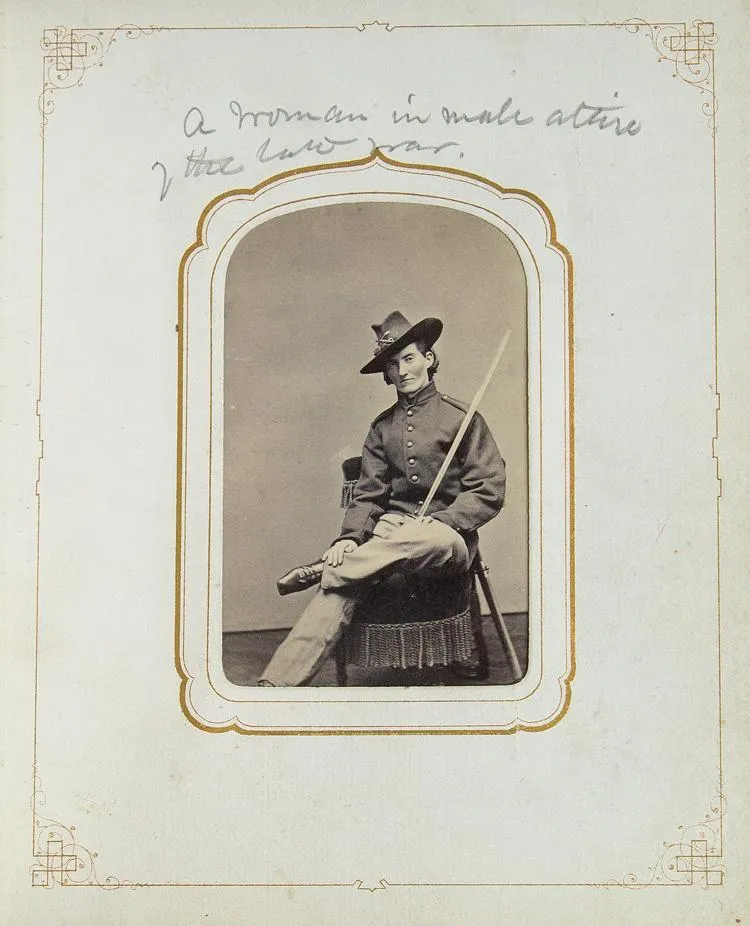

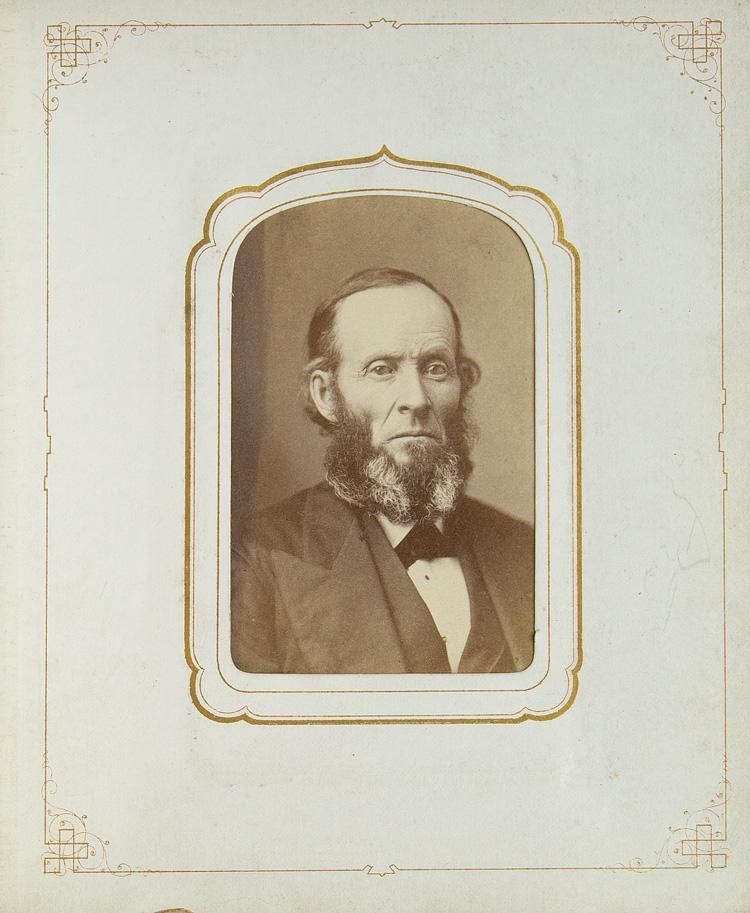

Other images include Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, an anti-slavery orator and author; Frances Clayton, a white woman who disguised herself in male attire and joined the Union Army; and Leonard Grimes, founder of Twelfth Baptist Church. Also included is a bust portrait of abolitionist Calvin Fairbank, who helped the Haydens escape Kentucky and was later captured, tried and jailed. It was Lewis who subsequently freed Fairbank, raising the required funds to release him.

In much of the day’s media, African-Americans were cruelly portrayed as inferior, and the popularization of cartes de visite may have marked the first opportunity for many of those pictured in Harriett Hayden’s album to present themselves exactly as they wished to be regarded by society. Theo Tyson, a visiting scholar at the Athenaeum says, “[The portraits] offer a sartorial resistance. There is fashion equity in their presentation. They don’t appear as enslaved, former slaves, or even abolitionists. They appear as people of their time unlike anyone else that would be walking the streets of Boston.”

Curiously, Hayden’s own image doesn’t appear in her albums and neither does that of her husband, though a sketched portrait appeared in Harriet’s obituary and handsome photographs of Lewis are easy to find online. Two sets of notations exist throughout the pages, one of which is believed to be Harriet’s penmanship. Many subjects are identified by name with the occasional witty remark. In the inside back cover of one album one of the hands glibly concludes, “3 pictures I like in this book.” Buchtel says the Athenaeum will run a handwriting analysis comparing the penmanship to a sample of Hayden’s writing from another source. The second hand remains a mystery that the Athenaeum will have to sleuth out.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/59/a1593082-0a08-4304-93e3-b6ab73628e30/07_boston_athenaeum_second_floor_horiz_img_8794.jpg)

The library plans to first conserve with new bindings, and then the institution’s curators will conduct research to confirm the identities of as many of the portraits’ subjects as possible—using watermarks from photography studios printed on the back of the images, as well as public ledgers, military records, clips from The Liberator, a leading American abolitionist newspaper of the day, and account books from the Boston Vigilance Committee, an organization that funded the sheltering of escaped slaves.

Curators will also examine the clothing and hairstyle trends such as flatteringly buttoned bodices, three-piece men’s suits, and ornately braided “updos” as clues to date the photographs. Lewis opened a successful tailor and shoe shop in Beacon Hill in the 1850s, and it’s entirely possible that some of the portraits feature his creations.

The acquisition and future plans for the albums are a part of the members-only library’s larger attempt to shed its reputation as an elite Boston Brahmin club and steer toward a more inclusive future. In the next few years, the albums will be digitized and made accessible online, as well as shown in a future exhibition, which will be open to the general public.