Hazel Ying Lee circled the biplane, looking for anything suspicious. Missing something on a precheck could cost you your life. She checked the engine and confirmed that no oil had collected in its lower cylinder.

Starting a Fleet biplane involved choreography. Lee grasped the propeller with one hand and pulled it backward. “Just walk it through. You don’t need to use force,” her instructor, Al Greenwood, yelled from the cockpit. She repeated the process four times; each time, she heard the click that told her she’d done it correctly. Then, with both hands on the propeller, she raised her left leg forward. Swinging it behind her for leverage, she pulled, and the unique thumping that identified the Kinner engine began.

After climbing onto the wing and into the cockpit, Lee inspected the instrument panel, starting with the fuel. The tank held close to three hours of fuel when full. If a car ran out of gas or had engine trouble, the driver could pull to the roadside. In flight, the best you could hope for was to find a good field, and quickly.

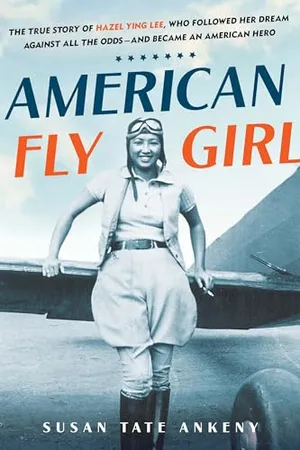

American Flygirl

One of World War II’s most uniquely hidden figures, Hazel Ying Lee joined the WASPs and flew for the United States military amid widespread anti-Asian sentiment and policies.

As 19-year-old Lee performed her preflight check in July 1932, Greenwood’s other training biplane, called the Student Prince, taxied down the runway, piloted by one of the Chinese Flying Club of Portland boys earning solo hours. Founded in 1931, Greenwood’s school trained Chinese American pilots to go to China and help defend against the invading Japanese.

These young men would become a vital part of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s stand against the invasion. As the head of China’s Nationalist government, Chiang and his party were trying to establish control in a nation divided among revolutionists, nationalists, Indigenous warlords, and a developing communist army and government. Now, Japan seemed determined to take China’s resources. Many Chinese Americans supported Chiang and believed he would help China emerge from years of strife and discord.

China’s fledgling air force, with barracks and hangars still being constructed in the north, was easily defeated by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force. The Chinese needed pilots. Delegates traveled to the United States to scout out flying schools that could teach young Chinese American pilots to fly for China. Across the country, branches of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA), a group made up of local merchants and businessmen, agreed to help raise funds to train the young men.

The association was established in 1882 with the purpose of aiding and protecting Chinese Americans by providing assistance with housing, jobs and other issues that arose. Portland residents Chan Lam and Ting Lee made impassioned speeches to raise money for an aviation school, ultimately raising enough money to sponsor 36 local students. Chinese flight schools opened not only in Portland but also in Boston, San Francisco, Los Angeles and other cities across the country. In total, around 200 Chinese American pilots would undergo training at these schools before joining China’s defense against Japan. Before a student was accepted into the program, he had to pledge his life to China, to the interests of China and to Chinese aviation. The pledge to die for China would take precedence over any personal relationships that might develop.

Greenwood had purchased the Prince exclusively for the students in his Chinese flying school. He was essentially running two businesses simultaneously. With the new school under his direction, most of his time was spent training young men for combat in China, but he continued to give private flying lessons to students like Lee.

Greenwood’s first class of 15 boys quickly became idols to Lee. For as many hours as she could spare, she watched them practice. They treated her like a kid sister, though all of them were about the same age, and good-naturedly tolerated her enthusiastic antics and questions. She was fun to have around, laughing and playing tricks on them, with a wide smile and deep-voiced wisecracks.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/5d/0c5d6e50-ddc7-4d35-a6c2-59571cfad775/hazel-reszied.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/81/37/813715cb-056e-4b4b-9f02-107ae7b502d3/5a_lee_hazelnew.jpg)

Lee had kept the photo of the first class that appeared in the Oregonian newspaper in January 1931. Looking like a motley crew of street urchins, the young men posed in front of the Prince, uncertain of what they were in for before Greenwood began his process of transforming them into pilots bound for war.

Lee had never been among others who shared her passion for aviation. Flying was all that Greenwood’s students talked about, and they knew as much about airplanes—and sometimes more—than experienced pilots. It was practice that they needed, practice flying. And Greenwood would provide it.

The “boys,” as Greenwood called them, proved to be able students, a little heavy on the control stick at first, but never lacking courage or a willingness to try anything. Training required ten hours of primary work and ten hours of advanced aerobatics from each student—an enormous task for one instructor. Other pilots were hired to provide instruction to the students.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6e/b2/6eb2a174-4146-43ef-af42-17e04c4dcf2f/3c_afg_airshow.jpg)

Greenwood peppered his instruction with stories of his exploits, like one about his narrowest escape, to demonstrate the deadly consequences of fear. While practicing spins with a student, he’d turned the plane over at 7,000 feet and let it spin for about 5,000 feet. The student grabbed the stick, panicking, and, as a magazine article about Greenwood described it, “began to do things, all of which were wrong,” while using up nearly every one of the remaining 2,000 feet before Greenwood finally regained control—just before the wheels hit the tips of the grass. Controlling fear was essential no matter what happened in the air.

Born in Portland in 1912, Lee was the second of eight children born to Chinese immigrants. After she discovered her love of aviation at age 19, Lee began dressing like a flier, in baggy pants tucked into riding boots. People stared and pointed, talking behind their hands. “There’s the girl who is learning to fly.” “So foolish.” “Her poor mother.”

One evening, Lee and her friend Elsie Chang sat on the schoolyard grass in the gathering twilight, while Lee dramatically explained everything about flying, as if she were taking Chang along for a ride. Lee described what she could see while flying, how she steered the airplane, how the air made the plane rock and bounce, and all the dangers that needed to be avoided, like stalling on a landing. To Chang, it all sounded terrifying.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a2/9f/a29f5cdc-104a-42e5-bd00-5b2474ed2ec2/7a_mss_330c4307.jpg)

Lee was such a good storyteller that Chang closed her eyes and felt the wind and the weightlessness and heard the engine and smelled the trees in the air aloft. They fell back on the grass and stared up at the darkening sky, waiting for the first star to flicker.

Lee told Chang that no other Asian American woman had a pilot’s license in the United States. She was going to be the first.

Lee counted the minutes until she could get back in an airplane, with the wind in her face and the lulling rumble of the engine to soothe her. She loved the speed, the rhythmic, percussive thump of the engine, the rush of air surrounded by the silent expanse of sky. Lee experienced a new kind of solitude. Away from her family and the tight quarters of a home filled with younger siblings, an elevator operator job where she had to try to be invisible, she was alone without any expectations or judgments. It didn’t matter that she was of Chinese descent. No one could see her race; no one could see her gender. In the sky, she wasn’t Chinese or American, man or woman, visible or invisible. She was just herself. In the sky, she felt limitless.

Lee refused to be tied to a home and children when there were more exciting things to do. She saw how conformity ruled women’s lives, offering a suffocating security in return. Women moved from their fathers’ homes to their husbands’, where their sons would have more power than they ever would. For most women, groomed to deny their own capabilities, to distrust themselves and defer to men, the decision to fly was fraught with fears, not only of flying but also of being independent. In an age when women were encouraged to stay grounded, Lee’s desire to fly was the ultimate expression of individuality. A husband might insist she give up flying, and that was something she would never do.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/19/8a/198a3c46-3801-4973-98f2-215d303e2046/image-hazel_ying_lee.jpeg)

If Lee could convince Greenwood and the CCBA to accept her into the next class of students training to go to China, she would sign the pledge without hesitation. To fly against the Japanese invaders would be the ultimate experience and worthy of any sacrifice. She’d die in battle fighting the enemy without any regrets. But the Chinese Flying Club, like all the related programs across the country, didn’t allow women. Lee decided that needed to change. There were few opportunities for a Chinese woman already. If she wasn’t admitted to Greenwood’s flying school, her future options were not just limited, they were unthinkable.

In August 1932, Greenwood’s first class of 15 students eagerly awaited their departure for China, still heady from newspaper interviews and farewell speeches delivered at banquets in their honor. Four of the original 19 had failed to complete the class due to physical handicaps such as colorblindness. The proud graduates ready to embark on the adventure of a lifetime posed in front of the Prince in two rows, wearing tentative smiles and looking like boys not used to being photographed. Most wore ties, a few wore crewneck sweaters over white shirts, and several wore the bomber-style zip-up jackets popular at the time. They had learned more than flying under Greenwood’s guidance; they now believed themselves to be confident young men, no longer boys, ready to fight a war and, if necessary, die for China.

While the men of the CCBA wondered if these kids would have the toughness required to survive combat, Greenwood expressed an unwavering faith in his students. In an interview with Webster A. Jones of the Oregonian, Greenwood tried to deflate the accepted belief that people of Chinese descent could not possibly be as capable as white American pilots. “Chinese make rattling good fliers,” he said. “This myth about Orientals not being able to fly is pure bunk. They are as good as Americans—or other Occidentals—in natural ability, and they are superior in a lot of ways.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/79/05/7905e14d-0462-4f71-a8ea-8d7f11c7d297/6a.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/4d/b64dcd04-950e-4f04-b142-85288c8c989a/6b.jpg)

After the graduates were photographed, Greenwood invited his other flying students to pose for a photo. Lee sauntered over to stand in front of the Prince, wearing wide khaki jodhpurs tucked into black riding boots, a polo shirt and a flight vest. Her goggles had been pushed up onto her flight cap. She took a drag from her cigarette and leaned back on the wing.

Greenwood recognized Lee’s transformation. She moved in a slow, confident stride, with a graceful swagger. Over the summer, she had made rapid progress and would soon fly solo. In a few short months, she had come into her own, and in doing so, had become something completely unique. Greenwood understood her need to be first, to compete with the boys and the girls, too. He smiled and nodded toward her as the camera shutter snapped.

Lee was as talented as any of the male fliers, but the CCBA had not yet granted permission. Since the Chinese elders and businessmen supporting the school paid all the training expenses for the students, they had to be convinced that girls were worth the investment. Greenwood’s latest argument, that the grant to train 36 students had not stipulated they be boys, proved incorrect. The contract called for “young men.” He would have to convince them that Lee was a crack pilot worthy of their financial investment. She had to pass her flying test to receive her license first, but that wasn’t going to be any trouble for her.

Greenwood became a fierce advocate for Lee, telling the Oregonian that she had received the same training as her male counterparts and was just as capable as them, if not more so. He believed Lee would prove his long-held belief that flying involved more finesse than muscle, and that keen intelligence was more important than brute strength.

Besides helping China defend itself against the Japanese invasion and having the opportunity to fly, Lee had another reason for wanting to go to China. Her father’s children from a previous marriage—her half-siblings—as well as her aunts, uncles and cousins still lived in the village where her father had grown up. This could be her chance to fulfill her dream of visiting her father’s homeland.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e2/74/e274d7ce-d6eb-46e5-bcc7-53ef611c7236/5c_mss_25085.jpg)

On October 24, 1932, Lee passed the rigorous Department of Commerce pilot examination. Having also accumulated 50 flying hours, half of which were solo, Lee was granted a private pilot’s license. The document described her as a 5-foot-3, 117-pound woman. On November 1, the Oregon Journal reported on Lee’s achievement with the headline “Portland Elevator Girl Masters Flying and Gets License.” The reporter wrote, “The fifth floor of the H. Liebes & Co. [department store] was not high enough for Hazel Lee, 20, elevator operator there, so she got up early mornings to learn to fly an airplane. … Miss Lee took an airplane ride a year ago, got interested, and now that she can fly, she plans someday to go to China and interest women there in aviation.”

Lee was, in fact, the first Chinese American woman in the U.S., not just in Oregon, to earn a pilot’s license. (Katherine Sui Fun Cheung, born in China in 1904, earned her pilot’s license a few months before Lee and was the first woman of Chinese descent to do so in the U.S.; she later became a naturalized citizen.) Over the next decade, Lee would fly planes in both China and the U.S., becoming one of just two Chinese Americans accepted into the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) during World War II. She died at age 32 on November 25, 1944, two days after her plane collided with another aircraft and burst into flames. “Of the 1,102 women who [flew] in the WASP program, 38 died in service,” notes the Federal Aviation Administration. “Lee was the last.”

Adapted from American Flygirl by Susan Tate Ankeny. Published by Kensington Publishing Corp. Copyright © 2024 by Susan Tate Ankeny. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/73/48735891-e63f-4436-9706-ffd0117101df/hazel.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/susan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/susan.png)