Tillie Black Bear Was the Grandmother of the Anti-Domestic Violence Movement

The Lakota advocate helped thousands of domestic abuse survivors, Native and non-Native alike

:focal(918x778:919x779)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f8/14/f81476c5-3b4b-4505-9151-804bf062949c/gettyimages-51582056.jpg)

As a girl growing up on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota in the 1970s, Connie Brushbreaker sometimes saw her mother, Tillie Black Bear, beaten by the man who lived with them. It typically happened when Black Bear’s partner, a member of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe, was drunk. They’d be home watching TV or driving in her mother’s tiny green and black Mustang when he’d become violent.

Soon, though, Black Bear’s abuser did something she couldn’t take: He started hitting her young daughters. In response, Black Bear took his belongings, tossed them in her front yard and calmly told him to leave her house. He did.

Black Bear, who died in 2014 at age 67, went on to do more than anyone else in history to prevent violence against Native women and girls. “Before Tillie, no one was focusing on Native women in a national way,” says Suzanne Blue Star Boy, a prominent Native activist from the Yankton Sioux Tribe who worked beside Black Bear for many years. “She took in the national movement that was happening to raise awareness around domestic violence and refocused it on Indian Country.”

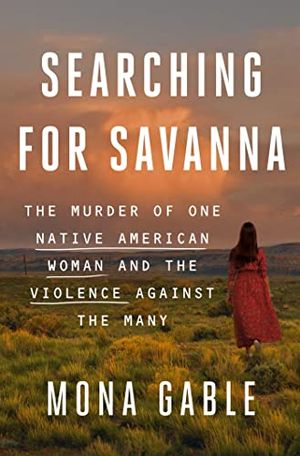

Searching for Savanna: The Murder of One Native American Woman and the Violence Against the Many

A gripping and illuminating investigation into the disappearance of Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind when she was eight months pregnant, highlighting the shocking epidemic of violence against Native American women in America and the societal ramifications of government inaction

But Black Bear rarely mentioned either her own hardships or her achievements. “She never really focused on herself. It was always on others,” recalls Brushbreaker, who now serves as director of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Diabetes Prevention Program. Indeed, over four decades of activism, Black Bear didn’t just make life safer for Native women—she helped establish the playbook for today’s anti-domestic violence organizations. Today, she’s recognized as the grandmother of what was then known as the battered women’s movement.

Black Bear was born in 1946 under the wide skies of the Rosebud Reservation, the third of 11 children. During her childhood, Native Americans were forbidden by federal law from practicing their spiritual ways. (It was not until 1978 that this cruel policy was ended.) Nonetheless, Black Bear’s family fought to keep their traditions. In the late 1950s, they traveled to Washington, D.C. to press Congress to allow Rosebud’s citizens to hold religious ceremonies in the open. They prevailed: “My family was one of the first ones that brought the sun dance back down to Rosebud in 1960,” Black Bear recalled during a 2008 lecture. Their example nourished her for life: “I come from that rich tradition of resistance, and it’s what helped me become who I am as a woman.”

Like countless Native children in the United States, Black Bear—a citizen of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe and the Sicangu Lakota Nation—was torn from her family when she was young. In first grade, she was forced to attend St. Francis Indian School, a nearby Catholic boarding school run by Jesuit priests and Franciscan nuns. At the time, she spoke only snippets of English. For years, she came home just twice a year: for Christmas and again during the sticky summers. Though she soon became fluent in English, she continued to speak Lakota at home. After graduating from the residential school, she attended college at Northern State University in Aberdeen, South Dakota, where she was one of a handful of female Native American students. She then went on to earn a master’s degree from the University of South Dakota.

Around this same time, the man she lived with also began beating her.

In the 1970s, few outside Indian Country paid much attention as more and more Native women were beaten, hurt and raped. The violence continued despite explicit federal trust obligations—written pledges given to tribes in exchange for Native territory—promising the government would work with tribes to keep everyone safe. Federal authorities didn’t track statistics documenting this pervasive brutality. But historians agree that the majority of violence was committed by white men emboldened by a lack of law enforcement on reservations.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a3/6a/a36a41f0-beed-4383-8fb0-f1d0ac5b853f/young-tillie.jpg)

On the Rosebud Reservation, Black Bear was keenly aware of the violence all around her—and of the appalling lack of government assistance. After kicking out her abusive partner in the early 1970s, she moved to protect her friends, first by opening her home as a refuge. “We always had people at our house,” says Brushbreaker. “And it was always women and kids. That was normal for us. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized we were a safe house.” Seeing how much her work was needed, Black Bear widened her networks of support and pursued a doctorate in counseling at the University of South Dakota, though organizing work ultimately prevented her from finishing the degree.

While working diligently toward her doctorate, Black Bear got a history-changing call from her friend Faith Spotted Eagle, the president of a new grassroots effort on the reservation to keep women and children safe. Called the White Buffalo Calf Women’s Society, it was grounded in Lakota teachings, particularly a centuries-old belief that, as the saying goes, “even in thought, women are to be respected.”

Spotted Eagle told her friend that after decades of silence, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights was finally holding a two-day symposium on the issue of domestic violence. Though the January 1978 hearings would primarily feature testimony from white women, Spotted Eagle had a big favor to ask: Would Black Bear go to D.C. to represent the society and Native victims more broadly? Well understanding the weight of this responsibility, Black Bear said yes.

Then in her early 30s, Black Bear was soft-spoken, unassuming and deceptively tenacious. At the civil rights hearings, she testified about the frequency of domestic violence in Indian Country. She described the poverty on Rosebud and the basic resources women there lacked in the face of domestic violence—counseling, health care, housing assistance, education, child care. “Distance is an important factor at the time of crisis, the need to get away from your spouse or from whoever the abuser [is],” Black Bear said. “This is hard to do in a small rural community where everybody knows you. … It is difficult to try to terminate [a] relationship because you get thrown in together at meetings, picnics, whatever type of social activities there are.”

In retrospect, the hearings were a landmark moment in the nascent movement against domestic violence. Never before had so many domestic violence advocates and survivors gathered from across the country to share their experiences. Never had women from so many backgrounds spoken so publicly and truthfully about the rapes and beatings they were enduring at the hands of their husbands, boyfriends and partners—an issue that had long been considered private rather than a social crisis that needed government intervention.

Poignantly, Black Bear was the only Native woman to speak at the symposium. Out of those hearings sprang the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, established that year with Black Bear as a founding member. Also in 1978, she established the South Dakota Coalition Ending Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault, which successfully lobbied for funding to support at-risk women.

After returning home, Black Bear threw herself into her advocacy. Working with the South Dakota Commission on the Status of Women, she organized the state’s first coalition meeting in June 1978. Nearly 80 women attended the historic event. “Women carried backpacks and sleeping bags and flew into Pierre, South Dakota,” Black Bear later recalled. “Women from across the country camped on our powwow grounds here at Rosebud.”

Around that same time, Black Bear opened a domestic violence shelter for abused and raped Native women on Rosebud. It was the first such shelter for women of color in America and operates to this day. At the time, though, her efforts to protect women on the reservation were not always appreciated. “Locally, she was not liked,” Brushbreaker says. Thanks to her work, “men were [being] held accountable, and women were starting to stand up for themselves.” Black Bear was called “a homewrecker, a lesbian, just really derogatory stuff.” Yet she famously never argued with her critics. “She just let things go because she always said it was just wasted energy,” Brushbreaker says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b6/27/b6273dcb-7d06-481e-a7d2-ea6b56d135a7/tillie-older.jpg)

In her speeches and lectures, Black Bear frequently emphasized the sacredness of Native women, reminding her listeners that for millennia, women were the ones who chose which men would represent their clan. If a man proved to be a bad leader, the clan would strip him of his tribal position. In marriage, meanwhile, Black Bear noted that Sioux women retained many rights. In her tribe, marriage ceremonies were quick, as were divorces. The tepee where the wife and husband lived was unquestionably hers. “All a woman had to do is gather his things and set them outside the tepee, and he knew then he was no longer welcome in her home,” she told her audiences.

Indeed, contrary to colonialist stereotypes of Native Americans, before European contact, tribes did not tolerate violence against women, including in marriage. Women were protected by tribal systems of justice—until the federal campaign to remove Native people from their homelands altogether eroded those systems in the 19th century.

Like many Native Americans who work to prevent domestic violence, Black Bear saw tribal sovereignty as essential to the movement to keep Native women safe. In 2013, when Congress added a significant tribal provision in the Violence Against Women Act, it restored tribes’ ability to prosecute non-Native defendants in Indian Country for domestic violence. Black Bear’s advocacy was pivotal in this crucial achievement.

The name of the White Buffalo Calf Women’s Society evokes a powerful, 2,000-year-old legend. Black Bear often recounted this ancient prophecy in her speeches. As tradition holds, long ago, two warriors were hunting for buffalo in the sacred Black Hills of South Dakota. A large shape inside a cloud appeared in the sky, drifting toward the men from the west. Soon the warriors saw that it was a white buffalo calf—a holy symbol to the tribe. As it came closer, the calf transformed into a beautiful young Indian woman. Seeing her, one of the young men had wicked thoughts. She beckoned him to come closer. The scout, being young and foolish, approached. As he did, the cloud turned black and enveloped him. When it lifted, nothing remained but his bones.

Now the second warrior began to pray. The White Buffalo Calf Woman gave him instructions: “Go back to your people and tell them that in four days I’ll come, bringing a sacred bundle.” On the fourth day, a white buffalo calf rolled off a cloud and became the beautiful young woman again.

That day, the White Buffalo Calf Woman taught the people songs, parables and the seven sacred ceremonies of life: the sweat lodge or purification ceremony, the naming ceremony, the healing ceremony, the “making of relatives” or adoption ceremony, the marriage ceremony, the vision quest, and the sun dance ceremony. As Joseph Chasing Horse, a member of the Lakota people, explains, “She instructed our people that as long as we performed these ceremonies, we would always remain caretakers and guardians of sacred land. She told us that as long as we took care of it and respected it, that our people would never die and would always live.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/62/c7/62c7bb4b-f64b-42ee-b7d3-4395130ce6a9/participant.jpg)

For Black Bear, these tribal beliefs sustained her as she crisscrossed the country, working to establish services for Native women and children. They also guided her as she continued to push for critical legislation in Congress, like the Violence Against Women Act of 1994.

When Black Bear died in July 2014, the mother of 3 and grandmother of 13 was laid to rest in South Dakota. In English, her Lakota name at birth, Wa Wokiye Win, means “Woman Who Helps Everyone.” It was a name that she came to fully embody. Every October 1, the beginning of Domestic Violence Awareness Month, Black Bear is celebrated and honored throughout Indian Country. Shortly before her death, she said, “Looking back over three decades, having spent most of my life as a woman in our resistance movement, I am so proud of our women who went beyond the shelter doors. … As tribal women, as Indigenous women, we are helping to create a safer, more humane world.”

Excerpted from Searching for Savanna: The Murder of One Native American Woman and the Violence Against the Many by Mona Gable. Published by Atria Books. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mona.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mona.png)