To Catch a Thief

How a Civil War buff’s chance discovery led to a sting, a raid and a victory against traffickers in stolen historical documents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/thief_apr08_631.jpg)

In the fall of 2006, a history devotee named Dean Thomas was surprised by something he saw on eBay, the online auction house. Someone was offering 144-year-old letters sent by munitions companies to Philadelphia's Frankford Arsenal, a major supplier of the Union Army during the Civil War. How had he missed these? Thomas wondered. Hadn't he combed the records of that very arsenal in that very conflict? "Boy, am I a dummy," he thought.

Thomas is the author of an impressive, if not best-selling, addition to Civil War studies titled Round Ball to Rimfire. Its three volumes explore every type of cartridge, ball and bullet used in the war—used, that is, by the North. With a volume on Southern munitions yet to come, the opus stands at 1,360 pages—yours for $139.90 from Thomas Publications, the company Thomas founded in 1986, according to its Web site, "to produce quality books on historical topics."

The company occupies a drab building west of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, that is as much museum as business, displaying old weapons as well as its books. Between stints of writing at home, Dean runs the business, and his brother, Jim, sets type, lays out pages and crops photos. It was Jim who first saw the Frankford Arsenal documents as he was hunting for a gift for Dean—a perpetual challenge, because Dean's got everything a history buff could want, or almost. "How many people do you know have a cannon on their porch and a Revolutionary War soldier's hut in their office?" Jim says.

Jim bid on two of the Arsenal letters. Their presence on eBay didn't alarm him, because old public papers can find their way into private hands in legitimate ways and be legitimately sold. What did worry Jim, though, was whether his brother would like them, so he asked him to peek online. Dean liked the letters enough to ask Jim to bid on a third.

Yet Dean, 59, kept puzzling over the letters, because even though he had meticulously tracked down all manner of Arsenal documents for his book, he couldn't remember seeing or hearing about these.

"He was kind of beating himself up for being a bad researcher," Jim says.

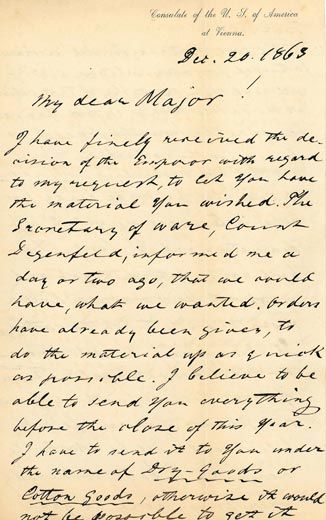

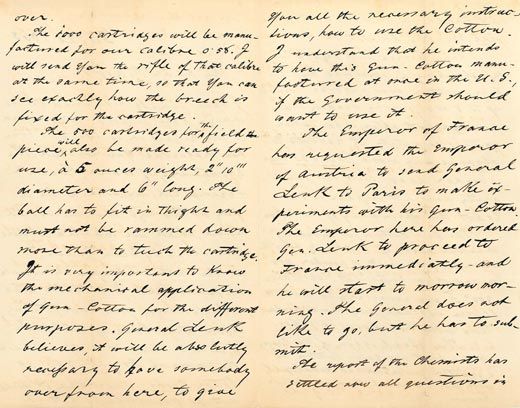

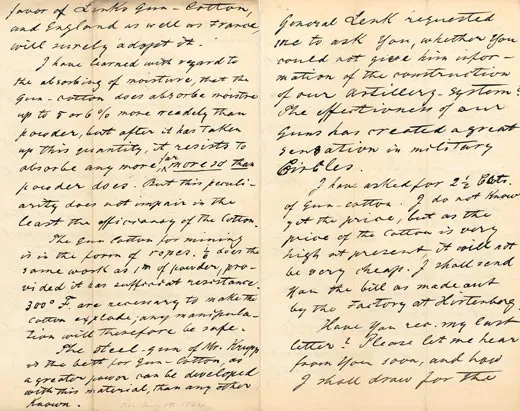

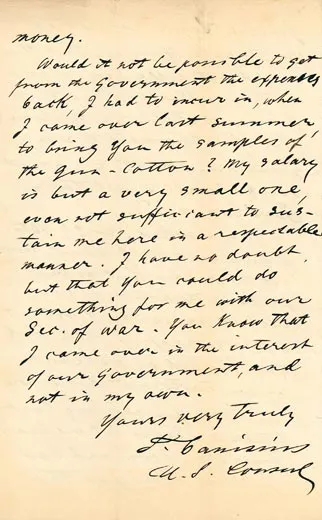

A few nights after he first saw the letters, Dean visited eBay to see if Jim's bids had won. He had, for $298.88. But now the seller had a new offering: another Civil War letter, this one sent to the Arsenal by an American diplomat. Its topic was an unusual type of Austrian ammunition called guncotton.

This time, vintage memories began to rustle.

Dean had devoted eight pages of his Round Ball opus to guncotton, specifically citing the diplomat's letter. He rose, went to his files and found a photocopy of it. He had made the copy more than 25 years earlier in Washington, D.C. because he could neither buy nor borrow the original. No one could. It belonged to the citizens of the United States.

The National Archives, he now had no doubt, had been robbed.

Searching his files further, Dean also found a photocopy of one of the three letters Jim had just won. That made two stolen items. After checking eBay again, Dean discovered that he had copies of two more documents up for sale. That made four.

They weren't big-deal documents—not letters from Jefferson to Adams—and they weren't worth much on the open market. But this was not a matter of fame or riches. This was about stewardship of the national story. Whatever doubts Dean had about his research talents gave way to anger at whoever was doing this. "He was peddling American history," Dean says of the perpetrator. "It wasn't his to sell, and he was a thief."

The next morning, September 25, 2006, Dean telephoned the Archives.

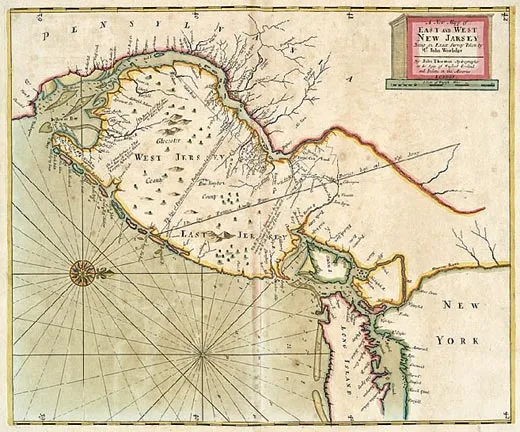

People of larcenous character have been tempted by rare documents for as long as libraries and archives have offered access to them. Pilfering a 16th-century map of North America or walking out with a letter bearing the signature of Jefferson Davis is the first step on the freeway to easy money because the world teems with buyers seeking an intimate connection with the past, something to frame on a wall or display on a coffee table.

Traditionally, the custodians of heritage have been leery of making too much fuss over thefts. After all, the filching of a historical treasure from a restricted and guarded room is embarrassing, and an admission of breached security could hurt funding or discourage potential donors from bequeathing their prized collections. But a string of recent high-value crimes has led not only to greater vigilance but also to greater frankness about the threat. The more the public knows of the trafficking in purloined history, the thinking goes, the more difficult the fencing.

"Please, please, please don't keep it quiet," Rob Lopresti, a librarian from Western Washington University, told an American Library Association gathering in June. If you stay silent about a theft, Lopresti added, "you're sleeping with the enemy."

In March 2000, a National Park Service worker saw an item for sale on eBay that he thought might belong to the Archives. It did. The agency, known formally as the National Archives and Records Administration, determined that an employee named Shawn P. Aubitz had whisked away several hundred documents and photos, including pardons signed by James Madison, Abraham Lincoln and other presidents. Aubitz was sentenced to 21 months in prison, but 61 of the presidential pardons are still missing.

During a six-year spree that ended in 2002, a Virginia amateur historian named Howard Harner repeatedly tucked Civil War papers into his clothes and strode out of the Archives. In all, he filched more than 100, including letters signed by Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant. Harner was sentenced to two years in federal prison; the Archives never got back most of what he took.

On February 21, 2006, a library employee at Western Washington University returned from the President's Day weekend to discover that someone had refiled books upside down or out of order in the government documents collection. In time, the staff determined that at least 648 pages of maps, lithographs, charts and illustrations had been torn from at least 102 vintage volumes. Evidence in that case led law enforcement authorities in December 2007 to a history-for-sale scheme that might have more victims than any in recent years, at least 100. (See "Pay Dirt in Montana," page 98.)

Above all there is E. Forbes Smiley III, an East Coast map dealer who, in January 2007, took up residence in a federal prison near Boston.

Smiley stole at least 97 maps from six distinguished institutions and sold them the old-fashioned way, privately, without eBay. A simple mistake stopped his spree: on June 8, 2005, a staff member found an X-Acto blade on the floor of Yale University's rare book and manuscript library. Told of the find, a supervisor noticed a man at a table examining rare maps and, using visitor logs, identified him as Smiley. Through an Internet search, the supervisor discovered that Smiley was a map dealer. A police officer found several Yale maps in Smiley's briefcase. After his arrest, five other libraries realized that Smiley had robbed them, too. "Nobody ever told me in library school I'd be on a first-name basis with an FBI agent," says David Cobb, the map curator at Harvard University, one of Smiley's targets.

The 97 maps were worth $3 million. But street value does not begin to capture the role of rare manuscripts, books and maps in illuminating a culture's milestones and missteps. When a car is stolen, its owner suffers alone. When a Civil War document disappears from an archive, everyone is diminished, even if just a little. It is no longer there to educate a Dean Thomas, who in turn cannot tell the rest of us about it.

Even though almost all the maps Smiley admitted stealing were recovered, the theft electrified the rare-document world because, as a high-end dealer, he had been family, trusted by the very institutions he had plundered. He had brazenly tossed aside the obligation to treat rare collections as community property instead of as a cultural ATM.

The New York Public Library was another of his targets, and in a statement to the judge in the case, library president Paul LeClerc wrote that "the maps stolen by Mr. Smiley provide a window into the past, illustrating how our predecessors once perceived of their relationship with the world and one [an]other." Losing such items to thieves causes "incalculable" damage, he added.

No less damage is done when manuscripts, books, photos and prints are torn—sometimes literally—from the public domain and sold into a life behind private walls. LeClerc may have been writing only about maps, but his words underscore the consequences when any rare and historical item is stolen from a great public collection: "Who knows what prize-winning book will not be written, or what historical or scientific discovery will not be made?"

When Dean Thomas telephoned the Archives, he was connected to Special Agent Kelly Maltagliati, a mother of two in her late 40s who used to stake out Florida swamps to nab drug runners for U.S. Customs. Maltagliati works at a building known as Archives II, which sits on a bucolic campus in College Park, Maryland, and is the modern-architecture sibling of Archives I, the stately tourist destination by the National Mall in Washington, a few miles away.

Besides records, Archives II houses the Office of Inspector General (OIG), which has the job of investigating thefts from the two main buildings, as well as from 13 regional centers, 12 presidential libraries and a slew of other facilities. So many papers, photos, artifacts and other pieces of Americana reside in those places that nobody can offer more than a ballpark number of the total. But the OIG knows precisely how many employees it has to recover anything stolen from them: seven, including Maltagliati and the inspector general himself.

"We're like the 300 spartans," Paul Brachfeld says, "less about 298."

As IG, Brachfeld has many duties, such as conducting audits of the Archives' operations, but he especially loves thwarting thieves. A wiry, intense man with a long federal career, Brachfeld, 50, radiates a kid's sense of wonder when he describes the thrill of holding recovered documents.

"We're a democracy. Democracy counts on records," he says. Some, certainly, are far more famous than others, but he will pursue the theft of any. "It's not for me to decide for the American public what's an important document or a relevant document or a critical document," he says. "They're all our documents. It's like deciding which child you like more in your family."

Protecting a family of documents is complicated by the very nature of the Archives and, indeed, of any special collection. Though rare books, maps and documents are not allowed to circulate like the latest best sellers, they are not locked away in vaults, either. They are meant to be requested and studied, and those who ask to inspect them are not strip-searched after they do so. Though security is extensive, it is possible to stuff an item inside a sock or shirt. President Bill Clinton's former national security adviser Samuel R. (Sandy) Berger strode out of Archives I with classified documents in 2003; he was ultimately caught and fined $50,000.

"If I come to the National Archives today and I have larceny in my blood, I can probably walk out and make some good money," Brachfeld says. "There are people that will do that."

Particularly after the Aubitz and Harner thefts, Brachfeld, who became inspector general in 1999, has pushed to make thievery more risky. "I want to make people scared," he says. He's hired an "investigative archivist" to help with cases; tightened security in rooms set aside for viewing documents; and cultivated "sentinels," people inside and outside the Archives who are alert to theft. If anyone—an employee, a private dealer, a citizen who loves history—sees a document for sale, "I want them to be somewhat skeptical, and be knowledgeable that I exist."

Dean Thomas, in other words, is Brachfeld's kind of guy, the kind who picks up a phone when he sees something amiss.

As soon as Thomas spoke with Special Agent Maltagliati, she had a suspect. This required no super-sleuthing. The seller's name had accompanied the eBay offers of Arsenal documents. Though it was possible that he had unwittingly bought them from the true thief, the name was a first-class lead. After hanging up with Thomas, Maltagliati phoned the Archives branch in Philadelphia, where the Frankford Arsenal documents had been been moved in 1980.

Until then, officials there knew nothing of a theft. But they certainly knew the name Maltagliati gave them: Denning McTague had just finished a two-month, unpaid internship at the Archives branch in Philadelphia. The conclusion was painfully clear. "I recall being really mad," says Leslie Simon, the director of archival operations at the branch.

McTague, who declined through his attorney to be interviewed for this article, was then 39, which might seem old for an intern. But his family business, Denning House Antiquarian Books and Manuscripts, had been struggling. So he had enrolled at State University of New York at Albany to pursue a master's degree in information systems in the hope of becoming a librarian, according to court records. Was hiring McTague unwise, given that his business involved precisely what the Archives held? "It gave me pause," Simon says. But his degree adviser had vouched for him.

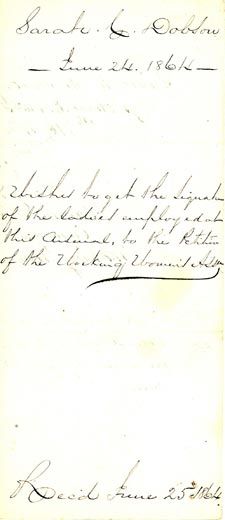

Among McTague's tasks was to sort through Arsenal files for items to help mark the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, which begins in 2011. Simon recalls that he sometimes showed her Arsenal documents he liked, including "some of the things he ended up taking."

So, by lunch on September 25, an often-nettlesome part of an investigation—who did it—was in all likelihood settled. But an equally critical riddle remained.

What, precisely, had the perpetrator done?

If a house is burgled, figuring out what's gone is usually no challenge. But major libraries and archives often have so many rare items that they haven't been able to make a proper record of each one. It's not always obvious they've been robbed even when they have been.

The University of Texas, for example, learned only in 2001 that its copy of a rare 16th-century book on lettering had been swiped as part of a larger theft in the early 1990s. The school had acquired the book when it purchased a large collection, but the volume had been stolen before it was recorded in the main catalog. Inventory checks never detected its absence. Only when the book appeared on an auction-house list years later did the university realize it was gone.

Last year, the Archives discovered that it owned a letter written by President Abraham Lincoln three days after the Battle of Gettysburg. It reflected his hope that Union Gen. George Meade would pursue the beaten Confederate Army because its destruction could end the war. Despite its obvious importance, the Archives had no clue it even had the letter until an employee found it while searching Civil War files to answer a reference query. "We have no item-level inventory," Brachfeld says. "We can't. We have billions of records."

In Philadelphia, the Archives knew that among the boxes in its 11 basement rooms were Frankford Arsenal documents, but it did not know the contents of each box. There was no easy way to find out what was no longer inside. Agents could raid McTague's house to recover what he had not yet sold. But if he wasn't keeping the documents there, and if he refused to cooperate after being arrested, the Archives might never know the total number he took or where he cached the remainder. So instead of going after the suspect immediately, investigators went after the documents. They would buy them on the open market, find the hiding place, or both.

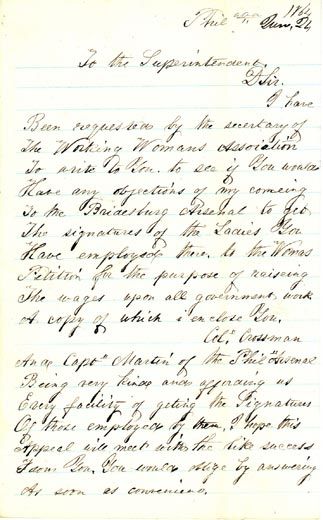

After making the 83-mile drive to Gettysburg, Maltagliati and a second agent crafted a sting operation. Jim Thomas would offer via e-mail to buy more documents from McTague, giving him a cellphone number so they could talk directly. If McTague called, however, the phone would be answered by an agent pretending to be Jim. If a buy could be arranged, the government would get firsthand evidence—and maybe a crop of documents.

But the sting would take a while. "With each passing day, these documents were at risk of being sold to third parties or being damaged," says Ross W. Weiland, the Archives assistant inspector general. Moreover, investigators were contacting people who had bought Arsenal documents, raising the likelihood that word of the pursuit would reach McTague. So, as the sting was being put in place, federal agents also tried to figure out from where McTague was mailing the documents he sold. If they could find out, they would go after what was left.

Simultaneously, in Philadelphia, Simon and the branch archivist, Jefferson Moak, were using the few clues they had to pin down what was missing from the Arsenal files. "They were working day and night," Maltagliati says. "I could tell by the e-mails I was getting at home."

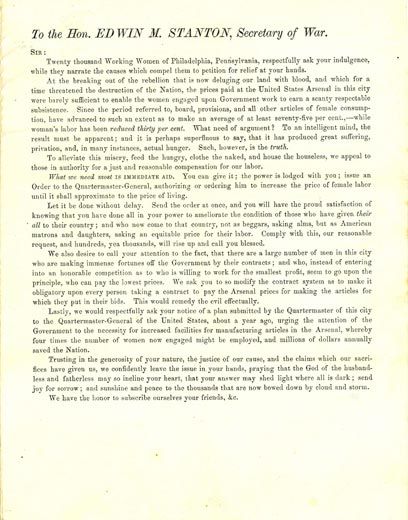

From eBay, of course, the pair learned not only what was for sale but what had sold. But they could not assume that was everything, so they used deduction to identify other stolen documents. For example, Arsenal officials had often replied to letters from munitions companies. If a copy of such a reply was still in the files, but the incoming letter to which the reply referred was not, McTague probably had it.

In time, the tally of the missing reached 164 documents. To this day Simon wonders if there are more.

Not long after dawn on October 16, 2006, a surprisingly formidable team of federal raiders gathered outside a row house on the fringe of downtown Philadelphia. Six were from the inspector general's office; two came from the Archives branch office and three were from the FBI. Some were armed and wore bulletproof vests. In part, a force of 11 showed how seriously the Archives took the case. It was also simple prudence. They were invading someone's world, someone who might be afraid and stressed. A suspect "can just go crazy," Maltagliati says.

Through the cellphone sting, agents had learned from McTague himself that he was keeping the documents in his first-floor apartment. So they got a search warrant, wanting to retrieve the papers before any could be lost or damaged.

Simon, 53, a career archivist, had never been on a raid, and recalls feeling "weird" about entering a dwelling uninvited. But she had a vital role: to identify what belonged to the United States. She brought along a list of possible items.

Except for a cat, no one was home.

Moments after entering, Simon saw an obvious place to look—a wooden map case of the sort libraries and map dealers use. About then, though, a neighbor appeared, having noticed a swarm of people inside the McTague apartment. That led, eventually, to a telephone number for a house in rural New York that McTague's family had owned for many years. An FBI agent dialed it. McTague answered. Within minutes, he confessed.

"First telephone confession I've ever seen," Eric W. Sitarchuk, McTague's attorney, would later tell a judge.

More than in many theft cases, the admission removed a huge hurdle, which is proving provenance—proving who originally owned an object. There is only one Mona Lisa, in the Louvre, and if it were stolen and recovered, there would be no doubt whose Mona Lisa it was. But the makers of a 16th-century map or 17th-century book usually made many "originals." Letter-writers made copies, too. So a suspect can claim that a vintage document in his possession was not stolen but obtained legitimately. The victimized library or archive might not have indisputable records to the contrary.

A task force of the American Library Association, assembled after the Smiley case, has proposed that institutions mark each map with a stamp of ownership in a place that "cannot be cut away without leaving an obvious incision," and that catalogs note unique features, such as stains, to distinguish each map from sibling originals. A modern, obvious ownership stamp on an old document is not a universally popular solution and marking tens of thousands of items would consume vast quantities of time and dollars. But, Harvard's Cobb says, "Any institution needs to make that commitment."

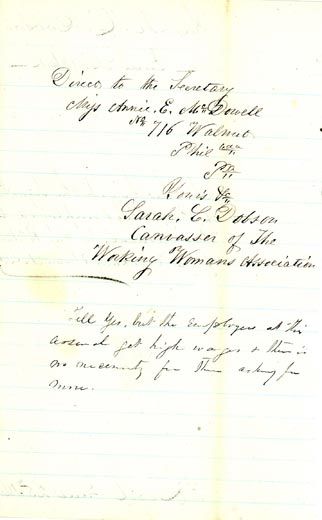

McTague's phone confession eliminated any need to prove that documents at his house or sold on eBay belonged to the American people. Checking the map case in his apartment, investigators found 88 Arsenal documents, all in good condition. Added to 73 documents recovered from eBay buyers, the Archives now had all but three of its missing documents. Those three seem to have disappeared, lost in the triangle linking McTague, his buyers and shipping companies.

By standard yardsticks, McTague was a candidate for leniency. He had no prior criminal record. He had cooperated. He had reimbursed every eBay buyer. The street value of his takings was relatively small, estimated by the Archives at $24,271.61. Finally, his career as a librarian was ruined, which was considerable punishment in itself.

On the day of sentencing, July 12, 2007, McTague entered Courtroom 10B of the federal courthouse in Philadelphia wearing the expression of a humiliated man. Behind the defendant's table, in the wooden pews, sat members of his family, including his wife. Nearby were Maltagliati and others from the Archives.

In a court filing, McTague's attorney had argued that no prison time was warranted. The crime was a "sad lapse in an otherwise honest and law-abiding life," Sitarchuk had written. McTague had "found adulthood, particularly making a living, an ever-growing struggle." Repeatedly, the lawyer went on, his client had been turned down for full-time library jobs, and the thefts had come at "a point of despair and despondency."

Wearing a blue blazer, beige slacks and a blue tie, McTague rose and stood at a lectern before U.S. District Court Judge Stewart Dalzell. "I've created a mess," began the defendant, a slim, bookish-looking man with glasses. He apologized to the Archives. He apologized to his family and began to weep. He apologized to librarians everywhere. "I'm so deeply sorry," he said.

In its court filing, the government portrayed the crime not as a lapse but as a calculated, money-making undertaking. In a statement to the court, Allen Weinstein, the Archivist of the United States, wrote that the theft had undercut "the fundamental integrity" of the Archives, because researchers would never know whether McTague took documents still unknown. He must be imprisoned, the government said, for at least 12 months.

To Dalzell, Weinstein's words were "extraordinarily powerful." The judge agreed that "this is an offense against everyone in this room." Original documents have an "absolute uniqueness," he said, and people "must be deterred from even thinking about" stealing them.

Fifteen months, Dalzell decided.

At various gatherings of memorabilia collectors these days, Inspector General Brachfeld's "investigative archivist," Mitchell Yockelson, sets up a table to distribute brochures on how dealers can spot stolen federal documents.

And these days every piece of outgoing mail at the Philadelphia branch of the Archives is inspected to make sure that no employee is mailing historic documents to a safe address to sell later. At the reference desk, two employees, not one, must be present when a visitor is using the "fishbowl," a glass-walled room where requested documents are brought for perusal. There were four interns last summer, down from seven the year before, the better to keep an eye on them.

But perfect security for a special collection or an archive will never exist, and their contents will never lose allure. Cobb, the map curator at Harvard, believes map losses might be rising as thieves try to satisfy buyers who have discovered that maps are historical, colorful and conversational—and not as expensive as traditional artwork. While most of the Archives' holdings are never going to fetch prices comparable to rare maps and old books, the Internet makes them just as easy to sell.

In the inspector general's office, Brachfeld knows that no matter how many cameras, guards and restrictions are out there, someone could be slipping a piece of the past between the pages of a yellow legal pad, just as Denning McTague did. "I don't know if this is a great day today, and not one record is being stolen from the National Archives," Brachfeld says, "or if, while you and I are talking, somebody's walking out of the building at this moment."

Steve Twomey, who has reported for several newspapers over three decades, wrote about Barbaro for the April 2007 issue.