Tombstone

In this Arizona outpost, residents revere the Wild West—and live it

In 1877, silver prospector Ed Schieffelin set out from Camp Huachuca, an Army post in southeastern Arizona, heading for the Dragoon Mountains. The soldiers warned him he’d find nothing there but his own tombstone. When Schieffelin struck silver, he named his mine Tombstone. By 1880, a town of the same name that sprang up around the mine was booming, with two dance halls, a dozen gambling spots and more than 20 saloons. “Still there is hope,” a new arrival reported, “for I know of two Bibles in town.”

A year later, Tombstone’s marshal was named Virgil Earp, who, with his younger brothers, Wyatt and Morgan, and a gambler named Doc Holliday, vanquished the Clanton and McLaury boys in a gunfight at the O.K. Corral. A Tombstone newspaper, the Epitaph, headlined its account of the event: “Three Men Hurled into Eternity in the Duration of a Moment.” The Earp legend has been dramatized in many Hollywood films, including the 1957 classic Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, starring Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas; Kurt Russell’s 1993 Tombstone and Kevin Costner’s 1994 Wyatt Earp.

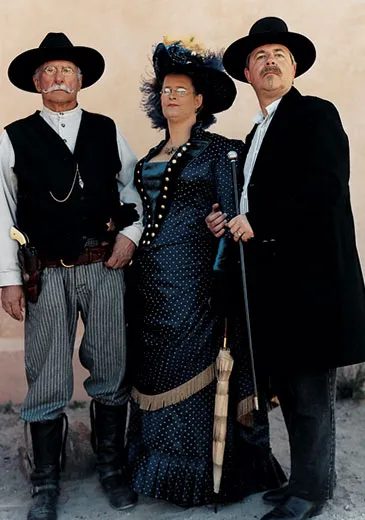

Having visited Tombstone in the 1970s, when the swinging doors of the Crystal Palace Saloon were virtually the only ones open and the O.K. Corral was populated by a mechanical gunfighter with whom, for a quarter, one could try one’s luck, I was drawn back recently by reports that the town had come to life again. Today’s Tombstone (pop. 1,560) still has the boardwalks, wooden awnings and false fronts of the original town, and the streets are still dusty with gusts of desert wind. But the old buildings have been given face-lifts, and a visitor wandering the historic district can buy everything from period clothing and jewelry to chaps, spurs and a saddle. Stagecoaches transport passengers around town; horses are tied to hitching posts; reenactors carrying shotguns stroll the main street; and women costumed in bustiers and skimpy dresses step in and out of the saloons.

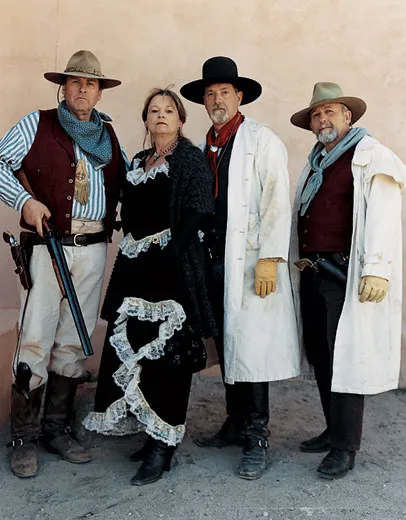

Locals refer to Fifth and Allen, the corner where the Crystal Palace Saloon stands, as “one of the bloodiest intersections in American history.” In 1880, Clara Spalding Brown, a correspondent for the San Diego Union, wrote of the violence: “When saloons are thronged all night with excited and armed men, bloodshed must needs ensue occasionally.” Today Six Gun City Saloon, employing local actors, offers five historic gunfight reenactments; a block away, Helldorado, a local theater troupe, performs shootouts. And the O.K. Corral hurls its three desperadoes into eternity each and every day.

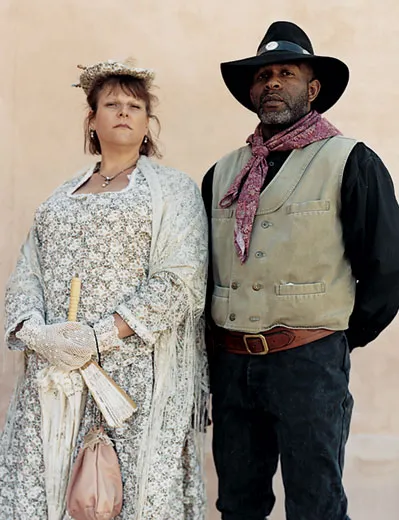

Tombstone has become something of a magnet for a new generation of residents—baby boomers who cut their teeth on early television westerns such as “The Rifleman,” “Have Gun—Will Travel,” “Wyatt Earp” and “Gunsmoke.” They’re people who came here on a whim, vacationers who saw a sign on the Interstate and fell in love with what they found.

At a saloon named Big Nose Kate’s, a group calling themselves the Vigilantes are sitting around a wooden table talking 1880s politics. A cross between an amateur theater group and a civic organization, the Vigilantes donate proceeds from their shootouts and hangings to community projects.

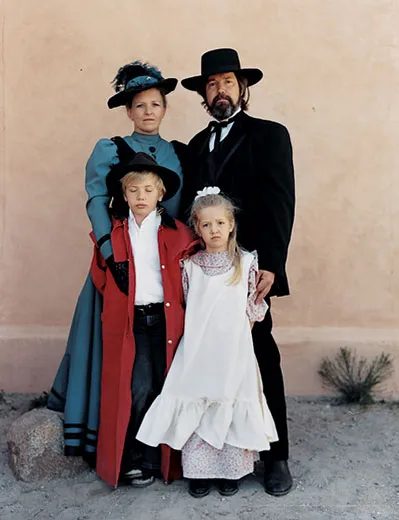

Vigilante Char Opperman wears a “madam outfit,” with lots of ruffles and lace trim; her husband, Karl, sports the britches, bandanna and hat of a cowboy. Says Char: “We were bored back in Illinois,” where Karl worked for the phone company and Char was a store clerk. “On the weekends we would say, ‘OK, what are we going to do now?’” They say they don’t miss the Midwest a bit. “It just wasn’t as satisfying as it is here,” says Char, though she admits she found it easier to change her address than her clothes. “It took a year to get me to dress up, but once you get in costume, your whole identity changes. Old friends visit us here and say, ‘You were this shy little thing in Illinois. Now you’re table dancing?’”

Some Tombstone men add a Winchester rifle to their wardrobe, but it’s the women who dress to kill. Most Vigilantes sew their own costumes and strive for authenticity, researching patterns in catalogs and era magazines. They can also buy reproduction clothes at the Oriental Saloon, which features a boutique stocked with chiffon, cotton voile, silk crepe, taffeta, lace and enough feathers to fill an aviary. “When the men get dressed, we’re strapping on leather and iron,” says Karl, “but it’s nothing to what the women wear.”

One of the attractions of Wild West frontier towns was the freedom they offered for shedding old identities and starting over. Some of that license survives in Tombstone, and no one seems to enjoy it more than Kim Herrig, proprietress of the Crystal Palace Saloon. After 20 years running an interior decorating business in Dubuque, Iowa, Herrig followed her partner, Mick Fox, when he landed a job as manager of the Tombstone Federal Credit Union in 1999. She bought the 1882 Crystal Palace, restored it and soon found herself rechristened by the saloon’s clientele as “Miss Kimmie.” “I’ve been known to get up and dance on the bar,” she says with a laugh. “It’s a whole new life.”

On a recent evening, the patrons of the Crystal Palace resemble the cast of a western movie. A party of young women near a pool table at the end of the bar are a study in ribbons, flowers and filigree, with tight corsets, swirls of petticoats and lace gloves. “I basically have to curl every single strand of my hair separately in order to have it fall into the ringlets,” says Trista Boyenga, who is celebrating her 24th birthday. She and her companions are from Fort Huachuca. “We’re military intelligence officers,” she says. “We’re all lieutenants.”

“Being an officer,” she goes on, “I have all these men saluting me, saying yes ma’am, no ma’am. My God, I’m 24 years old and I’m a ma’am already! I try to get away from that in Tombstone.” Her friend Heather Whelan agrees. “The military is very cut and dried, you’re a professional, you tell people what to do,” Whelan says. “In the military, we all look the same. And then you go to Tombstone and you’re the center of attention and people are buying you drinks and...you’re a girl again!”

While many people moved to Tombstone for adventure, James Clark sought it as a refuge. Now the owner of the Tombstone Mercantile Company, stocked with western antiques and collectibles, he raced locomotives into ambushes or train wrecks and performed other high-speed stunts in more than 200 Hollywood films. (Recently, he went back to his old job with Steven Spielberg for a six-part movie series, “Into the West,” on the cable network TNT.) And he keeps his hand on the throttle by running a freight train from time to time, between the Arizona town of Benson and the Mexican border. But most days he enjoys the slower pace of life as a Tombstone merchant. He built a stockade-like house outside town, modeled after one he’d seen on a movie set. “I live in the very area where the people I love to read about lived,” he says. “This is a place you can play cowboy Halloween every day of the week.”

At Old West Books on Allen Street, Doc Ingalls leans against the door frame. His mustache, his battered hat, even his slouch, are pure cowboy. As he looks on, a tourist asks a passing sheriff when the next gunfight is scheduled. The sheriff, in a big, wide-brim hat, says he doesn’t know. The tourist asks again, insistently. Ingalls steps out into the street and takes the visitor aside. “He’s the real sheriff,” he tells the tenderfoot. “You don’t want to be in a gunfight with him. He uses live ammunition.”