Top 10 Historic Midterm Elections

While not as memorable or studied as presidential campaigns, the midterm elections also stand as pivotal moments in U.S. history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/midterm-elections-631.jpg)

Congressional elections, held in the middle of a president’s term, are usually referenda on a president and his policies. Only twice has a president’s party gained seats in his first midterm election. But among all midterm elections, some have been more consequential than others.

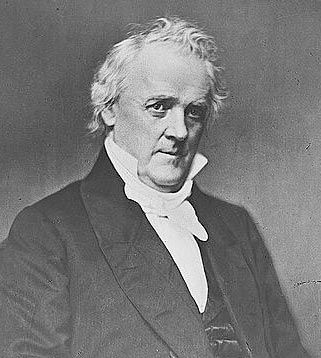

1858: the House is divided. Facing a recession and a nation bitterly divided over slavery, President James Buchanan (D) lectures the people on the virtue of thrift and backs a dubious pro-slavery constitution for the nascent state of Kansas. As the Democrats fracture, the Republican Party, founded only four years before to prevent the expansion of slavery, takes a plurality in the House of Representatives. Many Southerners say they’ll secede if a Republican is ever elected president. And after Abraham Lincoln (R) wins in 1860, they do.

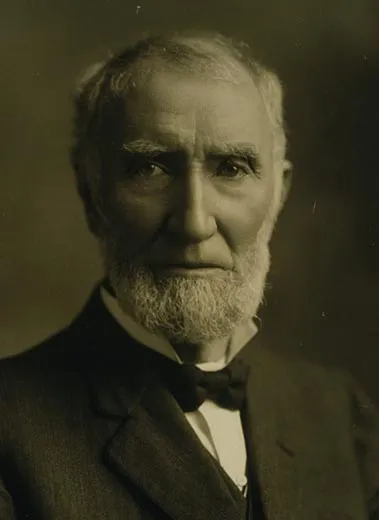

1874: deconstruction. Two years after President Ulysses S. Grant (R) is re-elected, scandals in the White House, a financial panic and concerns over post-Civil War governance in Southern states cost the Republicans 96 seats and their majority in the House, which they have controlled since 1858. When disputed electoral votes cast the result of the 1876 presidential election into doubt, Congressional Democrats are strong enough to force a compromise: Rutherford B. Hayes (R) enters the White House and federal troops leave the South, effectively ending Reconstruction.

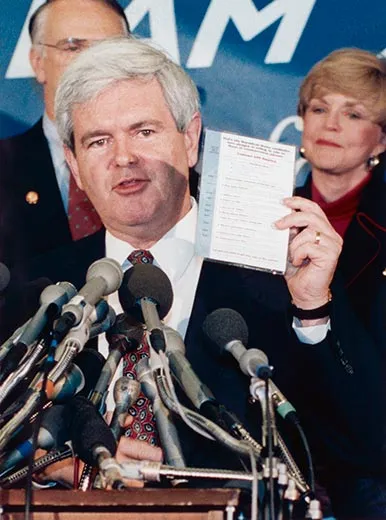

1994: Republican revolution. After President Bill Clinton (D) takes three tries to find a suitable attorney general nominee and falls short in efforts to overhaul health care and eliminate the ban on gay men and lesbians serving in the military, the GOP takes both houses of Congress for the first time since 1952. The Democrats’ loss of 53 House seats and 7 Senate seats is a “bloodbath,” analyst Kevin Phillips writes. Pundits advise Clinton to tack to the center; they also note increasing partisanship in Washington. He takes the advice and wins re-election in 1996 … and two years later the GOP-led House impeaches him on charges related to the Monica Lewinsky scandal. The Senate acquits him.

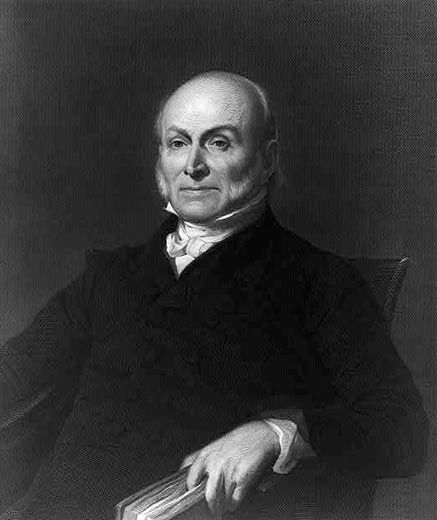

1826: era of hard feelings. The founding feud of the United States, between advocates of limited and less-limited government, seems to fade in the so-called Era of Good Feelings, from 1815 to 1825. “Party spirit had indeed subsided through the Union to a degree that I should have thought scarcely possible,” John Quincy Adams, an active-government advocate, observes in 1817. Actually, party spirit is just reorganizing; the Federalist Party has collapsed and the Democratic-Republican Party is splintering. Adams takes the White House in 1824 as a National Republican. In 1826, his party loses both houses of Congress. In 1828, the new Democratic Party, organized under the energies of Martin van Buren, runs Adams enemy Andrew Jackson for president and begins a whole new era.

2002: odds defied. Historically, the party of the sitting president loses ground in midterm elections. But in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks, Republicans counter the trend, gaining six seats in the House and two in the Senate with the help of aggressive campaigning by President George W. Bush. (This was the second time a president’s party gained House seats in his first midterm election. The first was the Democrats’ gain of nine seats in 1934 under Franklin Delano Roosevelt.) Bush, who took office in 2001 by virtue of a Supreme Court decision, now has majorities in both chambers (the Senate was split 50-50, leaving Vice President Dick Cheney with a tie-breaking vote) and a claim to a popular mandate as he pursues homeland security initiatives and a global war on terror.

1930: pessimism wins. In October 1930, one year into what will be called the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover (R) tells the American Bankers Association that “the income of a large part of our people is not reduced by the depression, but is affected by unnecessary fears and pessimism.” The next month, his perceived inaction on behalf of the unemployed costs the Republicans 49 House seats and 8 Senate seats, reducing their margins to 2 and 1, respectively. With party loyalties in play, Democrats begin assembling a formerly disparate lot of farmers, labor unionists, Southern whites and ethnic and racial minorities into a bloc that propels Franklin D. Roosevelt into the White House in 1932. Named the New Deal coalition, after FDR’s economic program, this bloc dominates American politics for decades.

1966: rejoinder to Johnson. When he seeks his first full term, in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson (D) crushes Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater (R) with 60 percent of the popular vote and 90 percent of the electoral vote. But two years later, after Congress passes laws on Medicare, voting rights and civil rights, and Johnson escalates the Vietnam War, the Democrats lose 47 seats in the House and 3 in the Senate, heralding the end of the New Deal coalition and the realignment of voters that will put Richard M. Nixon (R) in the White House in 1968.

1894: comeback and comedown. In 1884 Grover Cleveland becomes the first Democrat elected president since Buchanan, and in 1892 he becomes the only president to win non-consecutive terms. But his second administration features a severe depression, a railroad strike and an army of jobless workers demonstrating in Washington for relief. In the 1894 midterms, the Democrats lose 116 seats in the House—the biggest wipeout on record—and 5 in the Senate. The result vitiates the party everywhere but in the Deep South and prepares the ground for the elections of Republicans William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt to the White House and the rise of the modern presidency.

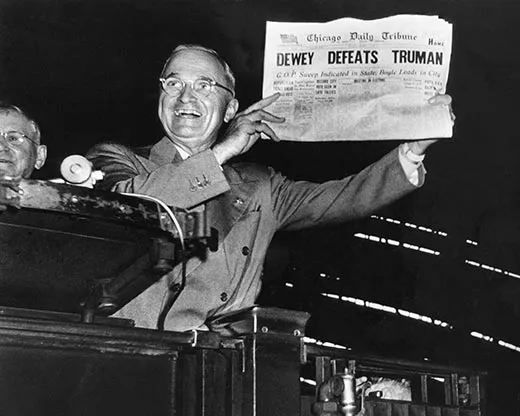

1946: nothing doing. After Franklin D. Roosevelt’s three-plus terms, Harry S. Truman (D) seems like a weak heir in 1945 as the nation contemplates the cold war world and a logy economy. The Republicans walk away from the 1946 midterms with gains of 56 seats in the House and 13 in the Senate—and majorities in both houses for the first time since 1928. But this proves to be a false portent: inaction on Truman’s legislative agenda gives him an opening to run against the “do-nothing Congress,” which he does in 1948, winning the Democratic nomination and then his own term as president.

1910: splitsville. In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt (R) picks William H. Taft as his successor and leaves for Africa. But over two years Taft alienates the progressive wing of the GOP over tariffs, natural resource conservation, workers’ rights and other issues. In the 1910 midterms, his party pays: 57 seats lost in the House, 10 in the Senate. With the Republicans splitting, he faces not only Woodrow Wilson (D) in 1912, but also a renegade bid from Roosevelt. Wilson wins with 42 percent of the popular vote.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)