Top 10 Nation-Building Real Estate Deals

Luck and hard bargaining contributed to the growth of the United States. But with expansion came consequences

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/US-land-deals-631.jpg)

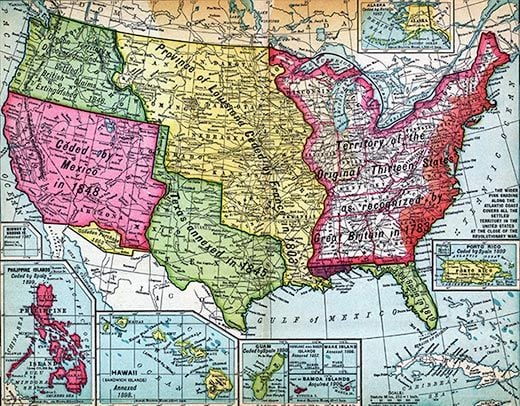

Despite the recent unpleasantness in the real estate market, many still hold (or once held, or will hold again) to the axiom of the late millionaire Louis Glickman: “The best investment on earth is earth.” This applies for nations, too. Below are ten deals in which the United States acquired territory, ranked in order of their consequences for the nation. Feel free to make bids of your own. (Just to be clear, these are deals, or agreements; annexations and extralegal encroachments don’t apply.)

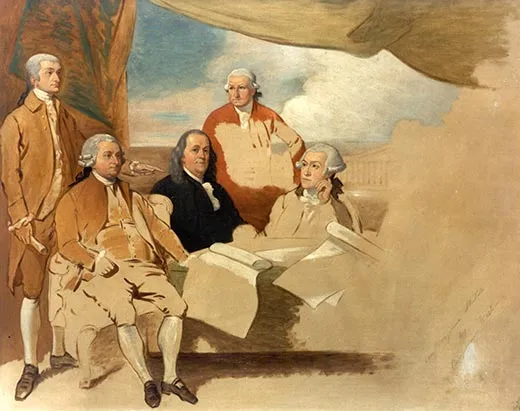

1. The Treaty of Paris (1783): Before the United States could start acquiring real estate, it had to become the United States. With this deal, the former 13 colonies received Great Britain’s recognition as a sovereign nation. Included: some 830,000 square miles formerly claimed by the British, the majority of it—about 490,000 square miles—stretching roughly from the western boundaries of the 13 new states to the Mississippi. So the new nation had room to grow—pressure for which was already building.

2. The Treaty of Ghent (1814): No land changed hands under this pact, which ended the Anglo-American War of 1812 (except for the Battle of New Orleans, launched before Andrew Jackson got word that the war was over). But it forced the British to say, in effect: OK, this time we really will leave. Settlement of the former Northwest Territory could proceed apace, leading to statehood for Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota, the eastern part of which was in the territory. (Ohio had become a state in 1803.)

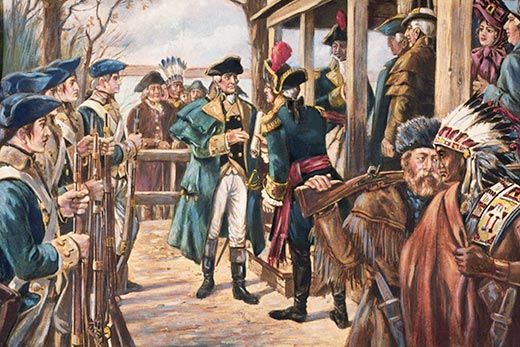

3. The Louisiana Purchase (1803): It doubled the United States’ square mileage, got rid of a foreign power on its western flank and gave the fledgling nation control of the Mississippi. But the magnitude of this deal originated with our counterparty, the French. The Jefferson administration would have paid $10 million just for New Orleans and a bit of land east of the Mississippi. Napoleon asked: What would you pay for all of Louisiana? (“Louisiana” being the heart of North America: from New Orleans north to Canada and from the Mississippi west to the Rockies, excluding Texas.) Jefferson’s men in Paris, James Monroe and Robert Livingston, exceeded their authority in closing a deal for $15 million. The president did not complain.

4. The Alaska Purchase (1867): Russia was a motivated seller: the place was hard to occupy, let alone defend; the prospect of war in Europe loomed; business prospects looked better in China. Secretary of State William H. Seward was a covetous buyer, but he got a bargain: $7.2 million for 586,412 square miles, about 2 cents an acre. Yes, Seward’s alleged folly has been vindicated many times over since Alaska became the gateway to Klondike gold in the 1890s. He may have been visionary, or he may have been just lucky. (His precise motives remain unclear, historian David M. Pletcher writes in The Diplomacy of Involvement: American Economic Expansion Across the Pacific, because “definitive written evidence” is lacking.) The secretary also had his eye on Greenland. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

5. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848): The Polk administration negotiated from strength—it had troops in Mexico City. Thus the Mexican-American War ended with the United States buying, for $15 million, 525,000 square miles in what we now call the Southwest (all of California, Nevada and Utah, and parts of Wyoming, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico). Mexico, though diminished, remained independent. The United States, now reaching the Pacific, began to realize its Manifest Destiny. On the other hand, the politics of incorporating the new territories into the nation helped push the Americans toward civil war.

6. The Oregon Treaty (1846): A victory for procrastination. The United States and Great Britain had jointly occupied 286,000 square miles between the northern Pacific and the Rockies since 1818, with the notion of sorting things out later. Later came in the early 1840s, as more Americans poured into the area. The 1844 presidential campaign featured the battle cry “Fifty-four forty or fight!” (translation: “We want everything up to the latitude of Alaska’s southern maritime border”), but this treaty fixed the northern U.S. border at the 49th parallel—still enough to bring present-day Oregon, Washington and Idaho and parts of Montana and Wyoming into the fold.

7. The Adams-Onís Treaty (1819): In the mother of all Florida real estate deals, the United States bought 60,000 square miles from Spain for $5 million. The treaty solidified the United States’ hold on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and pushed Spanish claims in the North American continent to west of the Mississippi (where they evaporated after Mexico won its independence in 1821… and then lost its war with the United States in 1848; see No. 5).

8. The Gadsden Purchase (1853): This time, the United States paid Mexico $10 million for only 30,000-odd square miles of flat desert. The intent was to procure a route for a southern transcontinental railroad; the result was to aggravate (further) North-South tensions over the balance between slave and free states. The railroad wasn’t finished until 1881, and most of it ran north of the Gadsden Purchase (which now forms the southern parts of New Mexico and Arizona).

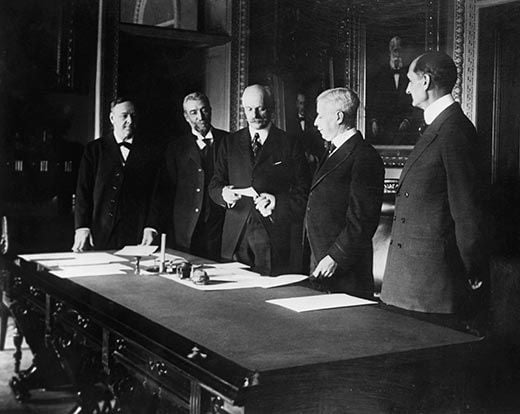

9. The Virgin Islands Purchase (1917): During World War I, the Wilson administration shuddered to think: If the Germans annex Denmark, they could control shipping lanes in the Atlantic AND the Caribbean. So the Americans struck a deal with the Danes, paying $25 million for St. Thomas, St. Croix and St. John. Shipping continued; mass tourism came later.

10. The Greenland Proffer (1946): The one that got away. The biggest consequence of this deal is that it never happened. At least since Seward’s day (see No. 4), U.S. officials had cast a proprietary eye toward our neighbor to the really far north. After World War II, the United States made it official, offering $100 million to take the island off Denmark’s administrative hands. Why? Defense. (Time magazine, January 27, 1947: “Greenland’s 800,000 square miles would make it the world’s largest island and stationary aircraft carrier.”) “It is not clear,” historian Natalia Loukacheva writes in The Arctic Promise: Legal and Political Autonomy of Greenland and Nunavut, “whether the offer was turned down... or simply ignored.” Greenland achieved home rule in 1979.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)