How Hurricanes Have Shaped the Course of U.S. History

A new book examines the 500-year record of devastating storms affecting the nation’s trajectory

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/62/5962dc99-8879-4854-922b-9cb90fbf2b3a/gettyimages-642059380.jpg)

Bryan Norcross remembers the moment well. It was 3:30 a.m. on August 24, 1992, and the meteorologist was in the midst of a 23-hour broadcast marathon as Hurricane Andrew, having reached Category 5 strength, bore down on Miami. He suggested to his crew that they move from the studio into an adjacent storage room, which was better protected from the fierce winds and slashing rains that were pummeling WTVJ-TV.

It was a wakeup call for many people who were watching on TV or listening on the radio. “Thousands of people over the years told me that was the moment they realized I was deadly serious,” Norcross recalls. “I had already told people to get ready to get under a mattress in a closet when the worst of it came in. That’s when many did, and four hours later they moved the mattress and could see the sky.”

Andrew was the most destructive hurricane to strike Florida, causing more than $25 billion in damage—about $46 billion today—with 44 deaths. Tens of thousands of homes, businesses and other structures were leveled as sustained winds of 165 miles per hour tore through the region. The storm would have a lasting influence.

“Hurricane Andrew is the storm that changed how we deal with hurricanes in the United States,” says Norcross, who now is a senior hurricane specialist at The Weather Channel. “The emergency management system was completely reworked. The hurricane building codes we use today came out of this storm. Also, it was the best-measured hurricane at the time. So much of what we know today about strong hurricanes is the result of Hurricane Andrew. It was a seminal storm in so many ways.”

The history of Atlantic hurricanes is inextricably linked with the history of this country, from its colonial founding through independence and into modern times. A new book coming out later this summer, A Furious Sky: The Five-Hundred-Year History of America’s Hurricanes by bestselling author Eric Jay Dolin, delves into the storms that shaped our society in ways we may not realize.

“I love the long arc of American history and love using it as a backbone to tell a broader story,” Dolin tells Smithsonian. “Hurricanes have determined some of the things that have happened in our country, including cultural issues, politics and the way society deals with concerns it faces: the women’s rights movement, racism, the evolution of television and more.

A Furious Sky: The Five-Hundred-Year History of America's Hurricanes

With A Furious Sky, best-selling author Eric Jay Dolin tells the history of America itself through its five-hundred-year battle with the fury of hurricanes.

Dolin begins more than 500 years ago with the hurricane of 1502. This massive storm in the Caribbean sank 24 ships of Christopher Columbus’ fleet off Hispaniola, the island shared today by the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The explorer, who had seen the hurricane approaching while at sea, warned residents of the Spanish settlement of the tempest and earned the distinction of becoming the first European to issue a weather forecast in the New World. The hurricane was also a harbinger of what was to come for those early colonies.

A century later, in 1609, a powerful hurricane nearly caused the collapse of England’s first permanent settlement in Jamestown, Virginia. Founded two years earlier, the colony was beset with problems from the start and relied heavily on aid from England. During the storm, a supply ship foundered and sank at Bermuda. By the time relief ships reached Jamestown, the colonists were near starvation.

“…Given the sorry state of the remaining colonists, the food on board the Deliverance and Patience was critical,” Dolin writes. “‘If God had not sent Sir Thomas Gates from the Bermudas,’ a contemporary pamphlet published in London opined, ‘within four days’ those colonists would have all perished.”

The meager rations that arrived enabled the settlement to barely survive until other supply ships arrived. One of the survivors, William Strachey, wrote about his ordeal, which William Shakespeare took as inspiration for the 1610 play The Tempest.

Farther up north, the Great Colonial Hurricane of 1635 clobbered the English settlements of Plymouth and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This storm felled hundreds of thousands of trees, destroyed numerous houses, sank ships and killed scores of people, including eight Wampanaog tribespeople drowned by the 14-foot storm surge. A man named Stephen Hopkins, who’d been on the supply ship that sank in Bermuda in 1609 and later an original passenger on the Mayflower, was serendipitously in Plymouth for this storm.

Dolin also cites a pair of storms that even helped the United States gain its independence. In 1780, two major hurricanes blasted through the Caribbean islands within weeks of each other, with the second, known as the Great Hurricane of 1780, killing an estimated 17,000 people. “[This] contributed to the French decision to get their ships out of the Caribbean the following hurricane season,” Dolin says, “which coincided with them sailing north and taking part in the Battle of Yorktown.”

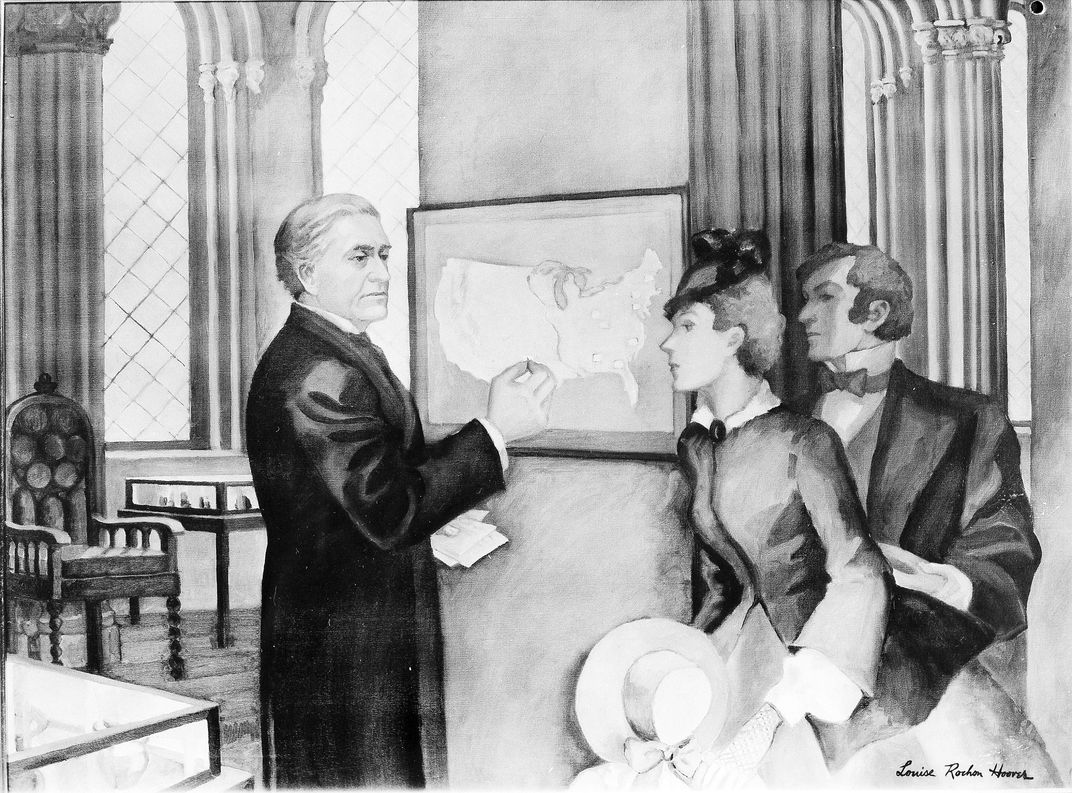

As the nation’s population expanded, particularly along the Atlantic Coast and in the Gulf, scientists and planners sought to learn more about predicting the paths of these super-storms and defend our cities against them. The first “real-time” weather map was developed by Joseph Henry, the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Though not used specifically to track hurricanes at first, in 1856 it used new technology to show the movement of storms across the eastern half of the United States with current data provided by telegraph operators.

“Joseph Henry helped shape the world we know when he laid the foundation of a national weather service shortly after becoming the Smithsonian’s first Secretary,” wrote Frank Rives Millikan, a historian with the Joseph Henry Papers Project. “…When Henry came to the Smithsonian, one of his first priorities was to set up a meteorological program. In 1847, while outlining his plan for the new institution, Henry called for ‘a system of extended meteorological observations for solving the problem of American storms.’”

No matter the plans set out, the science of the time couldn’t warn communities with enough time to avoid the big one, even as local communities may have had the knowledge at their behest. Along the Gulf of Mexico, for instance, locals could tell when a big blow was coming if the crawfish started moving inland. But government officials were still left unprepared when the giant Galveston Hurricane of 1900 sent a huge storm surge that swept over a barrier island. The area was packed with tourists for the summer season and the hurricane killed 6,000 people, though some estimates place the death toll even higher. The death and destruction inspired the building of a nearly 18,000-foot-long cement seawall, one of the first of its kind.

Dolin wonders if this catastrophe along the Texas coast might have been avoided or at least minimized if officials in this country had been more aware of what others were saying about the development of these storms in the Gulf of Mexico.

“A priest named Benito Viñes in Cuba had been an expert predictor of hurricanes during the late 1800s and actually coordinated his efforts with the United States,” he says. “But because the Americans looked down with condescension on Cubans and their science, they didn’t pay attention to some of the signs that led up to the hurricane in Galveston.”

The most powerful storm– with wind speeds of 185 miles per hour —to make landfall in the U.S. was the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935. The Category 5 storm killed hundreds of World War I veterans on the Florida Keys who had been moved there following the Bonus Army March on Washington, D.C. three years earlier. Novelist Ernest Hemingway, who helped with recovery efforts, wrote a blistering article titled “Who Murdered the Vets” critical of the government, writing “… wealthy people, yachtsmen, fishermen such as President Hoover and Presidents Roosevelt, do not come to the Florida Keys in hurricane months.... There is a known danger to property. But veterans, especially the bonus-marching variety of veterans, are not property. They are only human beings; unsuccessful human beings, and all they have to lose is their lives.”

More recently, more and more powerful storms have left their mark. Hurricane Sandy was a late-season arrival in 2012 that barreled up the East Coast and slammed the northeastern United States. Though only a Category 1 upon landfall, the massive “superstorm” fooled many forecasters since it took an unexpected track toward land instead of heading out to sea. Sandy caused $65 billion in damage and flooded many states, including highly populated areas in New Jersey and New York. Power outages shut down the New York Stock Exchange for two days, only the second time in history that weather had caused such a disruption in trading (the first was the Great Blizzard of 1888).

The advent of radar and satellites enabled meteorologists to track hurricanes with greater accuracy and reliability. In addition, modern computers that could predict the paths of storms have greatly enhanced forecasts to the point where weather experts can be reasonably sure of where they are going as much as five days out.

That ability was bore fruit in 2017, when three major hurricanes hit the nation in less than a month as Harvey, Irma and Maria laid waste to coastlines across the South and the Caribbean, particularly Puerto Rico. Damage caused by these devastating storms cost hundreds of billions of dollars with thousands killed. But it could have been worse.

“The only good news to come out of this bruising hurricane season was that the National Hurricane Center’s track forecasts were the most accurate they had ever produced,” Dolin writes. “So, people at least had a good idea of where and when the hurricanes would strike.”

Dolin argues that storms like these will increase in frequency and severity as climate change continues to cause the oceans to warm. “My book does not end on a high note,” he says. “We are in for a rough ride here on out. There is a growing scientific consensus that hurricanes in the future are going to be stronger and probably wetter than hurricanes of the past.”

Norcross, the TV weather forecaster who talked South Florida through Hurricane Andrew, sees an increase in serious storms this year and into the future. He says the average annual number of hurricanes over the past three decades was 12. Today, the figure has crept up to 14 or 15 per year. The odds now favor at least one storm of Category 3 or higher striking the U.S. each season. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts 2020 will spawn 19 named storms with as many as six major hurricanes.

Dolin says policymakers must not only get serious about reducing carbon emissions but also stop new development along shorelines and enforce tougher construction standards in coastal areas against the changes that are already coming.

“We have to have some humility about our place in the fabric of life and the world,” Dolin says. “Mother Nature is in charge. It is our responsibility to take actions that are wise and protect us as much as possible. We can’t bury our heads in the sand and assume the problem is going away – because it’s not.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)