The Tragedy of Cattle Kate

Newspapers reported that cowgirl Ella Watson was a no-good thief who deserved the vigilante killing that befell her, when in reality she was anything but

:focal(287x180:288x181)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/e0/21e04999-588d-4763-9e8d-17f0b94c4dff/gettyimages-517356782.jpg)

On July 20, 1889, in a gulch by the Wyoming’s Sweetwater River, six cattlemen lynched a man and a woman accused of cattle rustling. As the purported bodies twisted from the same tree limb: a rider galloped toward the town of Rawlins with the news: cattlemen had exacted revenge on two ruthless thieves, Jim Averell and Ella Watson, the woman they called Cattle Kate.

The story was shocking—it echoed across America like a shot, and only grew more dramatic in the retelling. One newspaper headline read: "Blaspheming Border Beauty Barbarously Boosted Branchward."

An account in the Salt Lake Herald painted Kate as a local legend, "of masculine physique, she was a dare-devil in the saddle; quick on the shoot; an adept with the lariat and branding iron." In a story in the National Police Gazette, a man asked Kate a question she didn't like. So she "knocked him down with a stunning left-hander and lashed him with her riding whip till he begged for mercy."

But the truth of the matter was likely much more anodyne. Kate was merely a woman looking to set out a life for herself on the frontier. Even though some local papers put out more accurate accounts soon after her lynching, the mythical version—wild woman meets her just end—is what stuck. Today, experts agree that Watson's greatest crime was probably her willingness to cross boundaries.

In effect, she was murdered for being different.

In the years after the Civil War, author Tom Rea explains in his 2006 book Devil's Gate, railroads had opened the West to the great wealth of the East. Beef, among other resources, could now be shipped long distances. Big ranches, owned by the land barons of their time, thrived in these unincorporated territories, profiting off the free grass on government-owned land and the cheap labor of cowboys. Some cowboys started their own, smaller herds by putting their own brands on mavericks—calves that had slipped unbranded through the roundups—a practice that was, for a time, legal. Some of the land barons paid their cowboys to brand their neighbors’ unbranded calves, which was more like stealing.

But in 1884, when the Wyoming Territorial Legislature outlawed the practice, unbranded calves were instead sold at auction, and cowboys and small landowners were frozen out of the process. To make matters worse, a saturated beef market, overgrazed ranges, a drought and cruel winter in the late 1880s knocked the bottom out of the business. The cattle boom went bust. Out-of-work cowboys looked to start small herds by any means. Barons blamed all their problems on cattle thieves, says Rea. People were shot, horses killed, and haystacks burned.

"Enter Cattle Kate," says University of Wyoming history professor Renee Laegreid. "One strike against her is that she's a small operator, and second strike is that she's a woman."

Ella Watson—tall, dark haired, sturdy--had a turbulent past. She married in 1879 at 18, and left her abusive husband in her early 20s to work at the railroad hotel in Rawlins, Wyoming. By 1886, she had met Averell and worked with him on the Sweetwater, helping run his store, selling goods like bacon and flour. She was homesteading with a small herd of cattle, and may have standardized her real estate holdings with her partner's understanding of land law—Averell was a postmaster, a notary public and a justice of the peace. Watson filed her own homesteading entry with the government on 160 acres, which meant that by the spring of 1888, she and Averell had claim to two 160-acre claims.

"Everything they were doing was legal," says Rea. "Jim Averell was a land surveyor and would have understood how the land law works, but the custom was that the cattle barons would control large pieces of land." Averell filed a land claim in the cattle barons' range, but then he flipped it, using that money to build his store instead of offering the land to the larger owners.

"The men who did the deed wanted his homestead and desert claim, with his fine water ditch running through it, the results of his five years' hard labor," Averell's brother, R. W. Cahill, told a reporter directly after the killings, trying to set the record straight. The grief-stricken Cahill called the lynching "cruel, and cold-blooded murder."

But Cahill's pleading was largely in vain; accounts of the lynching itself only fortified the idea of Watson and Averell deserving their fates. "The man weakened at once," said the Herald, "and began blubbering and whining. Kate was made of sterner stuff, and her blasphemy could not be approached in vileness or variety. She dared her maker to visit punishment upon her and cheat the lynchers. Averill [sic] and Kate were given a horse to ride to the scaffold. The woman jumped from the ground on to the horse straddle fashion, humming the wedding march."

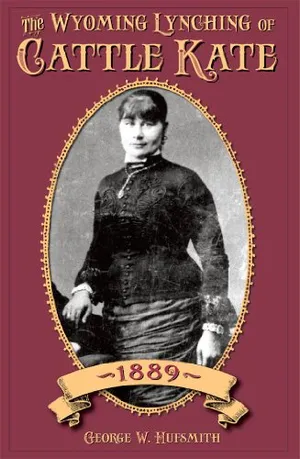

The Wyoming Lynching of Cattle Kate, 1889

The lynching of Ellen Watson and Jim Averell by six prominent and politically powerful Wyoming cattlemen rocked the nation in July 1889.

In reality, Watson wasn't a bar fighter or famous for horsewhipping cowboys. She was only guilty of standing up to a system run by big cattle companies. The newspaper accounts, with their florid, overwritten flair, were likely reflections of how the lynchers wanted the story told. Who could fault them for taking matters into their own hands when Watson was a villain who deserved to hang?

Besides its appealing alliteration—those two hard "k" sounds—Cattle Kate isn't a nickname ever used for Watson in life. It most likely came from confusion of Watson with a possibly fictitious woman named Kate Maxwell. Earlier newspaper stories in 1889 depict Maxwell as a heavy drinker who had allegedly shot a man for calling her "Katie," and would have been a beauty except for the scar on her chin. Brandishing a six-shooter, Maxwell supposedly took back several thousand dollars that cowboys she employed had lost to cheating faro dealers.

Laegreid says that the story that turns Watson into Cattle Kate—a bad woman punished—is part of the mythology of the Wild West as imagined by chroniclers like Teddy Roosevelt, Owen Wister, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Frederic Remington. That Ella Watson's story is known—even today--as that of Cattle Kate—shows the power of legend. The Cattle Kate myth resonates beyond its own framework, says Rea. "The fact that these guys on the Sweetwater were so unpunished--a lot of historians read that as the whole state and culture saying, I guess that's a perfectly reasonable way to take care of your problems."

The men who killed Watson and Averell never went to trial. No one could find two key witnesses, and the grand jury was made of 16 people, seven of whom were cattlemen. "The way I think about this lynching," says Rea, "is it's very much a story of law versus custom. And also, it's a story of just land use and neighbors. And it's a gender story too."

Even in Wyoming—famous for being the first state to give women the vote—women owning land and demanding rights irked many.

"Women weren't allowed to own property until the 1840s, and that was still very limited," says Laegreid. "It wasn't until 1862 that they could own it in their own right. That's still fairly new, and it did not fly well for a lot of men. We're still looking at the repercussions of the Civil War, and when women own land it's still seen as stepping outside of their role. And shouldn't they get married? Or shouldn't they give their land over?"

Watson's story illustrates the challenges women faced, even in a state famous for its forward-thinking approach to women's suffrage. "It's not quite as open and welcoming as the license plates might have you believe," says Laegreid. "The frontier may have looked bare and open but it was already part of this corporate dynamic," she says.

Rea agrees that the partners' willingness to step outside society's norms cost them. "Both Averell and Watson were-- just by what little we know of them--they were unafraid to be known for their opinions. He wrote letters to the newspaper accusing these guys of trying to sell lots in this fictitious town, and she seems to have been wiling to file land claims on her own. She also wasn't being timid or secretive." says Rea.

It's also a story of the shaping of history. In 1895, six years after the lynching, W. A. Pinkerton (the head of the Pinkerton detectives) told a reporter the story, calling Watson the "queen of a gang of rustlers." The early misinformation that the Cheyenne Daily Leader published was still being used as fact into the 1920s. Later historians recycled the narrative, too. It wasn't until two amateur historians wrote books on it that the real story gained wider traction for modern readers.

A 2008 article chronicled members of gathering of Watson's family at her grave in 1989. They were still trying to set the record straight. One descendant wanted her ancestor remembered "not as a hellion of a woman but a pioneer who got tangled in corporate power struggles and land rustling on the wild western frontier."

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.