A Train Company Crashed Two Trains. You Will Believe What Happened Next

When a Texas railway agent came up with a new marketing scheme, he had no idea how explosive it would be

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/4a/4d4a7c77-8bd1-4347-865c-ac3df15d76a4/crashcrushtx.jpg)

For the 2 million settlers of 1890s Texas, entertainment was hard to come by. Men could join a farmers’ group for business support and socializing, women had the Christian Temperance Union, and both could follow the developing rivalries of college football after the first game was played in 1894. But otherwise, opportunities for mass enjoyment were few and far between, which gave railway agent William Crush an idea: smashing two trains together purely for public spectacle.

Crush wasn’t the first person to propose such a display. A year earlier, railway equipment salesman A. L. Streeters had done the same thing in Ohio. One paper, which only briefly mentioned that a man had been injured by a flying bolt, called the collision “the most realistic and expensive spectacle ever produced for the amusement of an American audience.” But in September 1896, Crush, a passenger agent for the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad Company—more commonly known as the Katy—cooked up an even bigger the ultimate crowd-pleaser: a gladiatorial battle. Two 35-ton locomotives would ram into each other in “Crush,” a pop-up town erected for the occasion and named after the architect himself.

While the Katy brought in $1.2 million in passenger sales and $3 million in freight earnings in 1895, it still had some reason to be worried about its future. The economic depression of 1893 saw a quarter of the country’s railroad companies file for bankruptcy. In Crush’s vision, the stunt would promote the Katy and raise the visibility of his company.

But pinning down any real reason for the locomotive battle is a challenge, because railroads more generally were in Texas to stay, says Brett Derbes, the managing editor at the Texas State Historical Association. “Maybe part of the crash at Crush is for people to actually see a wreck,” Derbes says, adding that railroad accidents were common and deadly in that period. “Maybe this is a tourism thing. Maybe it’s a legacy thing. It’s certainly kept William George Crush’s name alive for more than just his job.”

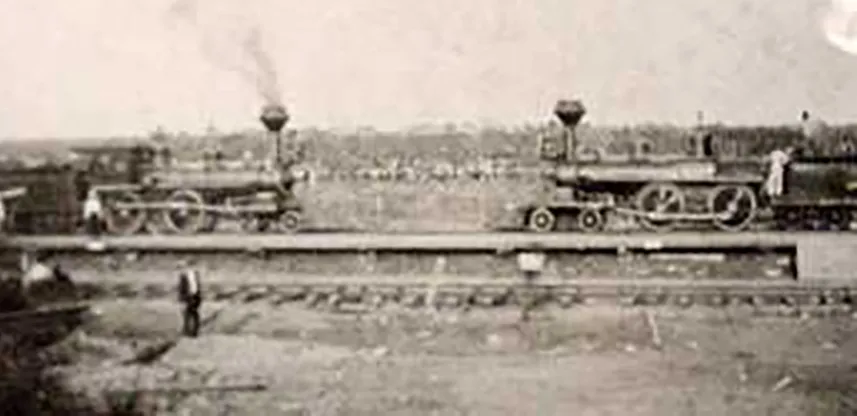

Whatever Crush’s motivations were, he managed to sway the Katy managers. For weeks leading up to the event, Crush and a fleet of workers scurried around the state in preparation. Crush found two 35-ton steam engines that were being retired for new 60-ton engines and commissioned them for the spectacle, after consulting with company engineers about the safety of the undertaking (only one suggested the collision might cause an explosion, and he was overruled). Engine No. 1001 was painted red with green trim, while its opponent, No. 999, was painted green with red trim.

A line of track was laid 15 miles north of Waco, just beyond the natural amphitheater of three tall hills. Crush drilled two wells and ran pipes for spigots, hired a man from Dallas to run a dozen lemonade stands, brought in tanks of artesian mineral water, erected a restaurant and even a wooden jail that would be patrolled by 200 hired constables. But the main attraction—apart from the trains themselves—was the row of carnival attractions based on Chicago’s highly popular Midway Plaisance at the 1893 World’s Fair. “This feature alone will be worth going to Crush [City] to see,” construction foreman A.D. Arbegast told The Galveston Daily News. “[This] is going to be the event in Texas this year.”

Other Texas papers seemed to agree. “Crush’s dream caught the Gay Nineties’ fancy,” wrote Kenneth Foree in Dallas News. “It spread, until people talked of little else: politics, the chief entertainment at Texas crossroads, went into hibernation until the wreck was over.”

On September 15, the day of the event, spectators poured into the temporary town of Crush, paying $2 to travel there by train from anywhere in Texas. By 10 a.m. a crowd of 10,000 had already amassed, and trains of people kept pulling up every five minutes. “Men, women and children, lawyers, doctors, merchants, farmers, artisans, clerks, representing every class and every grade of society, were scattered around over the hillsides, or clustered around the lunch stands, discussing with eager anticipation the exciting event that they had come so far to see,” reported the Galveston Daily News. The event turned out to be so popular that the collision had to be delayed, since trains were still arriving at the scheduled 4 p.m. showtime. Some 40,000 people came in total, briefly making Crush the second-largest city in Texas.

At 5:10, Crush himself came riding in on a white horse and waved his hat, giving the signal for the trains to start. The engineers and conductors onboard each behemoth got the trains moving, then jumped to safety about 30 yards from the starting point. As the two engines approached, they reached speeds of 50 mph, carrying a row of empty boxcars behind them. Their collision was every bit as astonishing as predicted—but it quickly turned violent, according to one reporter attending the event.

“A crash, sound of timbers rent and torn, and then a shower of splinters. There was just a swift instant of silence, and then, as if controlled by a single impulse, both boilers exploded simultaneously and the air was filled with flying missiles of iron and steel varying in size from a postage stamp to half a driving wheel, falling indiscriminately on the just and unjust, the rich and the poor, the great and the small.”

At least two people died, and many more were injured by the flying debris and scalding water that erupted from the boilers. The Waco photographer hired to take official photos of the crash, a man named J.C. Deane, lost an eye to a steel bolt. “One Confederate veteran said the smoke, explosions and people falling all around him was more frightening than Pickett’s Last Charge at Gettysburg,” writes E.R. Bills in Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional and Nefarious. Despite the injuries and shock of it, the crowd still rushed forward to claim souvenirs from the crash.

Crush was promptly fired, only to be rehired when managers at the Katy realized how successful the stunt had been in terms of publicity. They paid Deane $10,000 and gave him a lifetime railroad pass, and dealt with other claims as hastily as possible. Despite the accident, the line had become an overnight sensation, catching headlines in the international press.

“To me, I think it’s just incredible,” Derbes says. “This sort of thing could be staged in modern day and still be as interesting. Two light-rail trains going 100 mph and smash into each other—I think that would still be well-attended. The idea of the spectacle of a car or train crash raises everyone’s ears.”

The Missouri-Kansas-Texas went on to expand across the state in the following decades, earning more than $10 million by 1931. “[The Katy] not only opened a huge territory, but contributed to the general well-being of its service area by supplying economical and reliable freight and passenger service,” according to the Texas State Historical Association. And no one in the company’s long history ever forgot the “Crash at Crush”: today the collision is commemorated by a historical plaque in West, Texas, several miles from the site.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)