The Train Station That Has Been Housing the World’s Refugees for More Than a Century

Past and present collide at Berlin’s Ostbahnhof

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/5d/6b5dcc72-0a9c-441a-bb4b-7ac01c9f3304/3_hall_and_platforms.jpg)

Refugees from Syria and other war-torn nations have poured into Germany in recent weeks, making an arduous trek across Europe in search of safety and shelter. This year alone, an estimated 40,000 will come to Berlin, Germany’s largest city. Many are arriving on trains from Munich, disembarking into a new life at the Ostbahnhof, Berlin’s eastern railway station; it’s one of five serving long-distance travelers to the city.

Built in 1842, the station today resembles an airport terminal; its glass façade and modern skylights convey openness and transparency. It is a place for commuters, where visible traces of the past are hard to find. The ordinary surroundings – the streets of what was once East Berlin – belie the station’s remarkable life as a crossroads of east and west in Europe. Aside from a few monotonous buildings, relics of the proletarian past, there are no indications of the many stories the station can tell.

The refugee crisis presents the largest movement of people in Europe since the end of the Second World War. But the station, once known as “the gates to the East,” is no stranger to mass migrations. “Jewish migrants from Tsarist Russia arrived there,” explains Felizitas Schaub, a doctoral candidate in history at Berlin’s Humboldt University. “Poles traveled through the station in search of seasonal work in the West, and again on the way home. That’s why Berliners called it ‘the Polish station’ or the ‘Catholic station.’”

Between 1905 and 1914, some 700,000 Jews, fleeing pogroms and poverty in Russia, Romania and Poland, reached Germany, the overwhelming majority on trains to Berlin. Last month, Götz Aly, a historian in Berlin, reminded readers of the station’s Auswanderersaal, or “Hall for Emigrants,” a large room in which volunteers supplied refugees, many en route to the United States, with tea, advice, and even temporary housing. The hall was the work of the German Jewish Aid Society, a relief organization founded in Berlin in 1901 in response to an earlier refugee crisis.

A few decades later, Jews would once again travel en masse along the tracks leading east out of the station, but this time in the opposite direction, to ghettoes in Eastern Europe, and to concentration camps including Theresienstadt near Prague, and directly to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camps. From 1941 to 1943, an estimated 80,000 Berlin Jews were rounded up at three railway stations in the city and deported. All trains traveling east passed through today’s Ostbahnhof, whose tracks led to Poland and all the way to Vladivostok.

The station was inaugurated in 1842 as the Frankfurter Bahnhof, the terminus of a railway linking two cities in the Kingdom of Prussia: Frankfurt on the Oder, a small trading center in the east, and a fledgling Berlin. In the absence of a national state with a central regulatory authority, Berlin was one point on a jumbled map of competing and overlapping railways that often changed hands and names. In 1846, the station was called the Niederschlesisch-Märkischer Bahnhof, or “Lower-Silesian-Markish Station” a mouthful that indicated the extension of the line farther east, to the city of Breslau, which is today Wrocław in Poland. Until the formation of the German Empire in 1871, train tracks spread across the region like tangled weeds. But with Berlin as the capital of a unified Germany, the city emerged as the largest point in the network, the center from which routes radiated across the region. By the end of the 1870s, trains transported some 10 million people in and out of the city each year. Commuters, refugees, soldiers, manufactured goods, and coal for Germany’s growing industries flowed through the busy station.

The Frankfurter Bahnhof became the Schlesischer Bahnhof, or “Silesian Station,” in 1881, following a major renovation to meet soaring demand. The name came from its connection to the east, to the region of Silesia in present-day Poland. This was the height of the great railway age. Every European capital had a central station, and mega-metropolises like London, Paris, and Berlin had several. Silesian Station, which by 1902, boasted more traffic than any other in the capital, changed the face of the city. “The growing station transformed the area,” says Schaub. “It grew famous for its many nightclubs, cheap hotels and hostess bars. Greater traffic turned Silesian Station into a meeting place for travelers to and from Eastern Europe and Russia, but also for locals who enjoyed the area’s entertainment and who wanted to experience the sights and sounds of faraway places.”

Karl Schloegel, a historian at Viadrina University, sees the station as a metaphor for Berlin's 20th century: a cultural crossroads, or point of encounter between Europe's east and west, where the poor, huddled masses and exiles of the Russian Revolution remade the city. He titled his history of the German capital: Berlin: Europe’s Ostbahnhof.

Railways figured prominently in the imagination of Berliners. By 1920, the metropolis had become the world’s fourth largest, amid profound political and economic change. “Trains came to symbolize life in all its fleetingness and transience,” wrote Karl Ernst Osthaus in 1914, on the eve of the First World War. The Silesian Station, located in Berlin’s east end, a hub for refugees and transients in the city, soon became a shorthand for an urban underworld, its criminals and prostitutes, the “poor, weather-beaten, and dissolute creatures who wander about the streets at night."

A travel guide, published in 1913, warned visitors to avoid the “gray, dark sea of houses” in the vicinity of the station, which teemed with “dive bars, criminals, mafia.” In the stories of Joseph Roth and Alfred Döblin, famous chroniclers of life in Berlin in the 1920s, the station appears as a character, embodying the alienation of the modern age. At the train station, individuals were no longer individuals, but members of a mass public that shopped at department stores, went to shows and spectacles designed for huge crowds, and attended political rallies that attracted thousands of people. German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin recalled the train stations of his Berlin childhood as symbols of both the greatness and dubiousness of technology and progress.

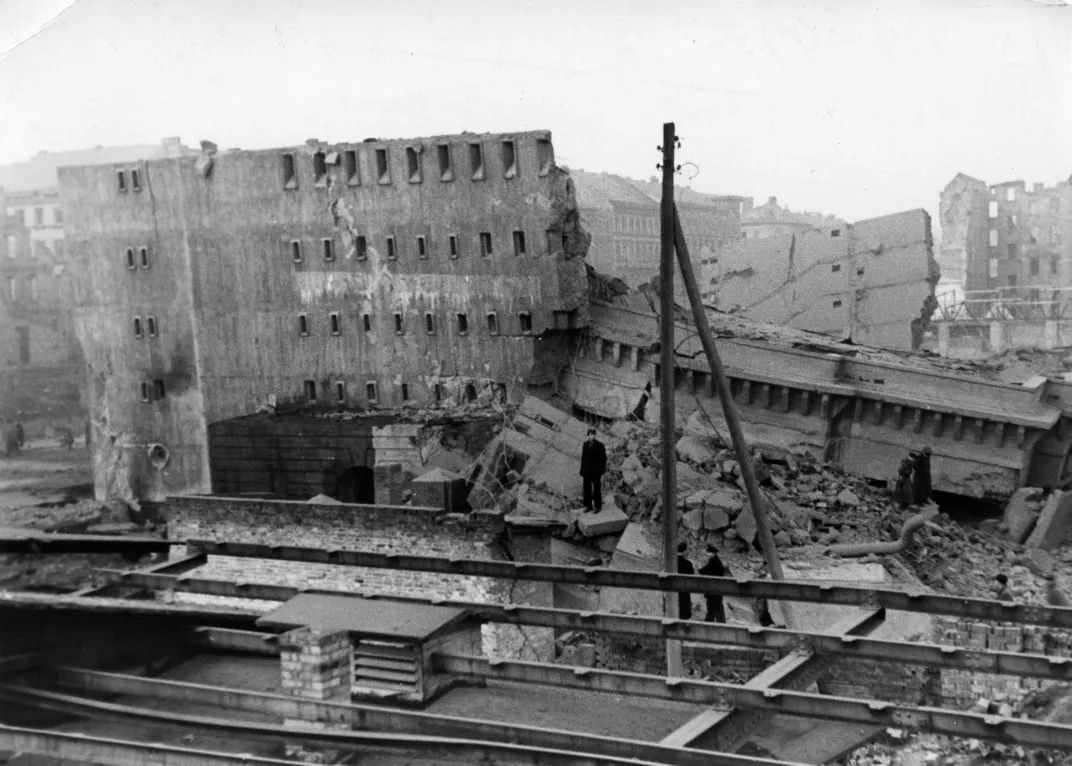

Benjamin’s worst fears were realized. From Silesian Station, units of the Wehrmacht, the armed forces of Nazi Germany, departed for Poland in 1939 and the Soviet Union two years later. The station was badly damaged by Allied bombs and conquered by the Red Army during the Battle of Berlin. Only the exterior walls of the station and basement survived. Under Soviet control, German workers made the station operational once again in time for Stalin to reach Potsdam by train, in the summer of 1945, to meet U.S. President Harry Truman and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In 1950, a new East German state, firmly in the Communist bloc, rebuilt the station and renamed it the Ostbahnhof. The revived station, a concrete monolith, now represented a regime obsessed with industry and the socialist collective. The party’s official ceremonies and parades revolved around the station, and youth organizations gathered there, singing revolutionary songs and brandishing red banners. The Berlin Wall, the ultimate symbol of a world divided, ran opposite the Ostbahnhof, the central station of East Berlin. Between 1987 and 1998, during another restoration of the building and repairs to its long-distance tracks, officials renamed the station Hauptbahnhof. Its resurrection as the Berlin-Ostbahnhof took place in a reunified Germany.

Can a train station be a character in history? Today’s refugees, traveling to Germany on trains, are once again putting train stations in the crosshairs of history. At Berlin's Ostbahnhof, and others in the city, relief groups offering assistance are continuing a tradition that began more than a century ago.