When 22-year-old Cassius Clay unexpectedly defeated Sonny Liston on February 25, 1964, football star Jim Brown, a close friend of the young athlete, expected to mark the occasion with a night of revelry. After all, in beating Liston, Clay was now the heavyweight boxing champion of the world, proving that his skills in the ring matched his reputation for bravado. As Brown, who narrated the match for an avid audience of radio listeners, later recalled to biographer Dave Zirin, he’d planned “a huge post-fight party” at a nearby luxury hotel. But Clay had another idea in mind.

“No, Jim,” he reportedly said. “There’s this little black hotel. Let’s go over there. I want to talk to you.”

One Night in Miami, a new film from actress and director Regina King, dramatizes the hours that followed the boxer’s upset victory. Accompanied by Brown (Aldis Hodge), civil rights leader Malcolm X (Kingsley Ben-Adir) and singer-songwriter Sam Cooke (Leslie Odom Jr.), Clay (Eli Goree) headed to the Hampton House Motel, a popular establishment among black visitors to Jim Crow–era Miami. The specifics of the group’s post-fight conversation remain unknown, but the very next morning, Clay announced that he was a proud convert to the anti-integrationist Nation of Islam. Soon after, he adopted a new name: Muhammad Ali.

King’s directorial debut—based on Kemp Powers’ 2013 play of the same name—imagines the post-fight celebration as a meeting of four minds and their approach to civil rights activism. Each prominent in their respective fields, the men debate the most effective means of achieving equality for black Americans, as well as their own responsibilities as individuals of note. As Powers (who was also the writer-director of Pixar’s Soul) wrote in a 2013 essay, “This play is simply about one night, four friends and the many pivotal decisions that can happen in a single revelatory evening.”

Here’s what you need to know to separate fact from fiction in the film, which is now available through Amazon Prime Video.

Is One Night in Miami based on a true story?

In short: yes, but with extensive dramatic license, particularly in terms of the characters’ conversations.

Clay, Malcolm X, Cooke and Brown really were friends, and they did spend the night of February 25, 1964, together in Miami. Fragments of the story are scattered across various accounts, but as Powers, who also penned the film’s script, told the Miami Herald in 2018, he had trouble tracking down “more than perfunctory information” about what actually took place. Despite this challenge, Powers found himself intrigued by the idea of four ’60s icons gathering in the same room at such a pivotal point in history. “It was like discovering the Black Avengers,” he said to Deadline last year.

Powers turned the night’s events into a play, drawing on historical research to convey an accurate sense of the men’s character and views without deifying or oversimplifying them. The result, King tells the New York Times, is a “love letter” to black men that allows its lionized subjects to be “layered. They are vulnerable, they are strong, they are providers, they are sometimes putting on a mask. They are not unbreakable. They are flawed.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/6b/826b682e-34c9-4836-8362-f132137a8c12/gettyimages-50613722.jpg)

In One Night in Miami’s retelling, the four friends emerge from their night of discourse with a renewed sense of purpose, each ready to take the next step in the fight against racial injustice. For Cooke, this translates to recording the hauntingly hopeful “A Change Is Gonna Come”; for Clay, it means asserting his differences from the athletes who preceded him—a declaration Damion Thomas, a sports curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), summarizes as “I’m free to be who I want to be. I’m joining the Nation of Islam, and I don’t support integration.”

The film fudges the timeline of these events (Cooke actually recorded the Bob Dylan–inspired song prior to the Liston-Clay fight) and perhaps overstates the gathering’s influence on the quartet’s lives. But its broader points about the men’s unique place in popular culture, as well as their contrasting examples of black empowerment, ring true.

As John Troutman, a music curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History (NMAH), says via email, “Cooke, Ali, Brown and Malcolm X together presented a dynamic range of new possibilities for Black Americans to engage in and reshape the national conversation.”

Who are the film’s four central figures?

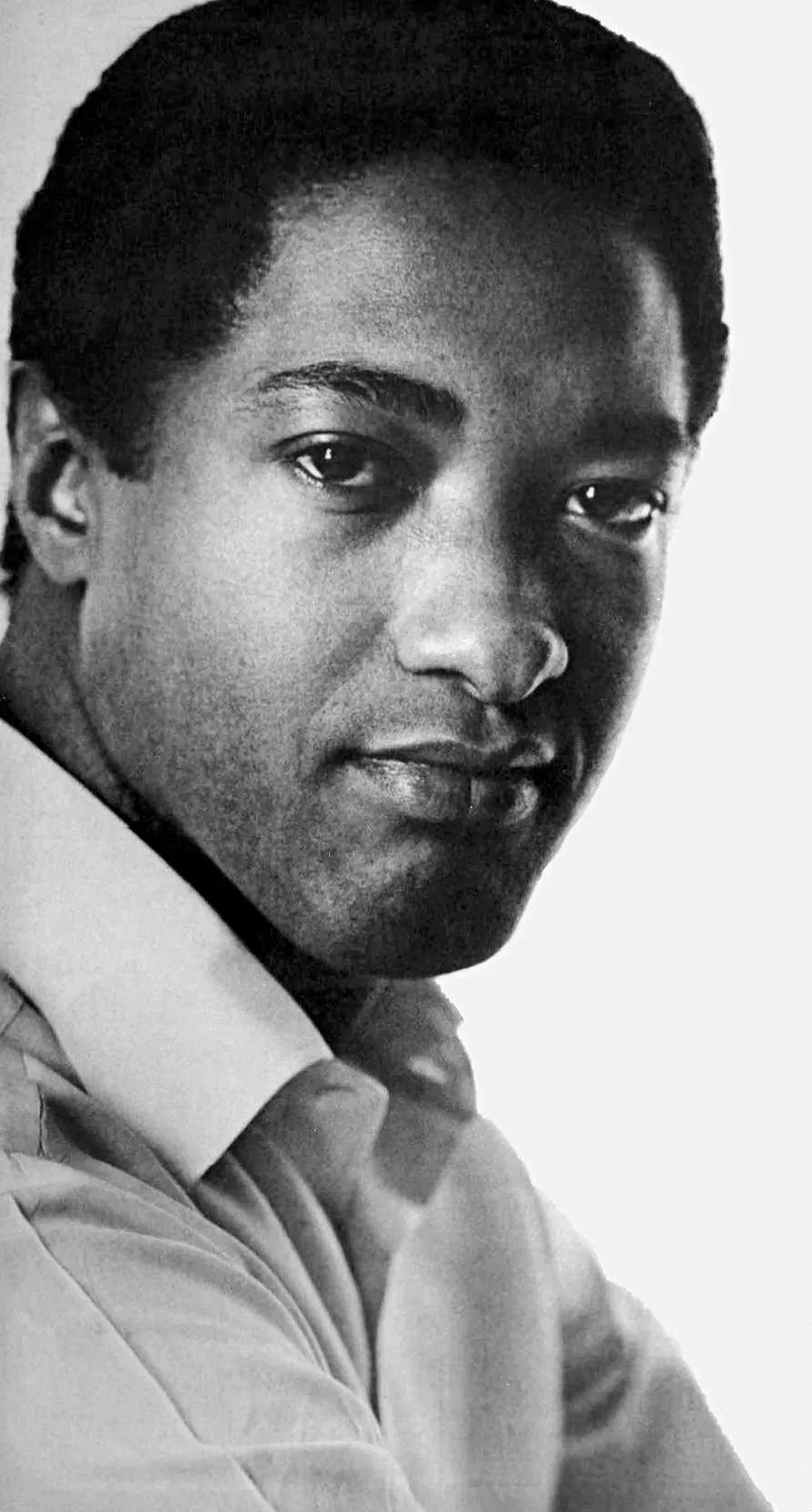

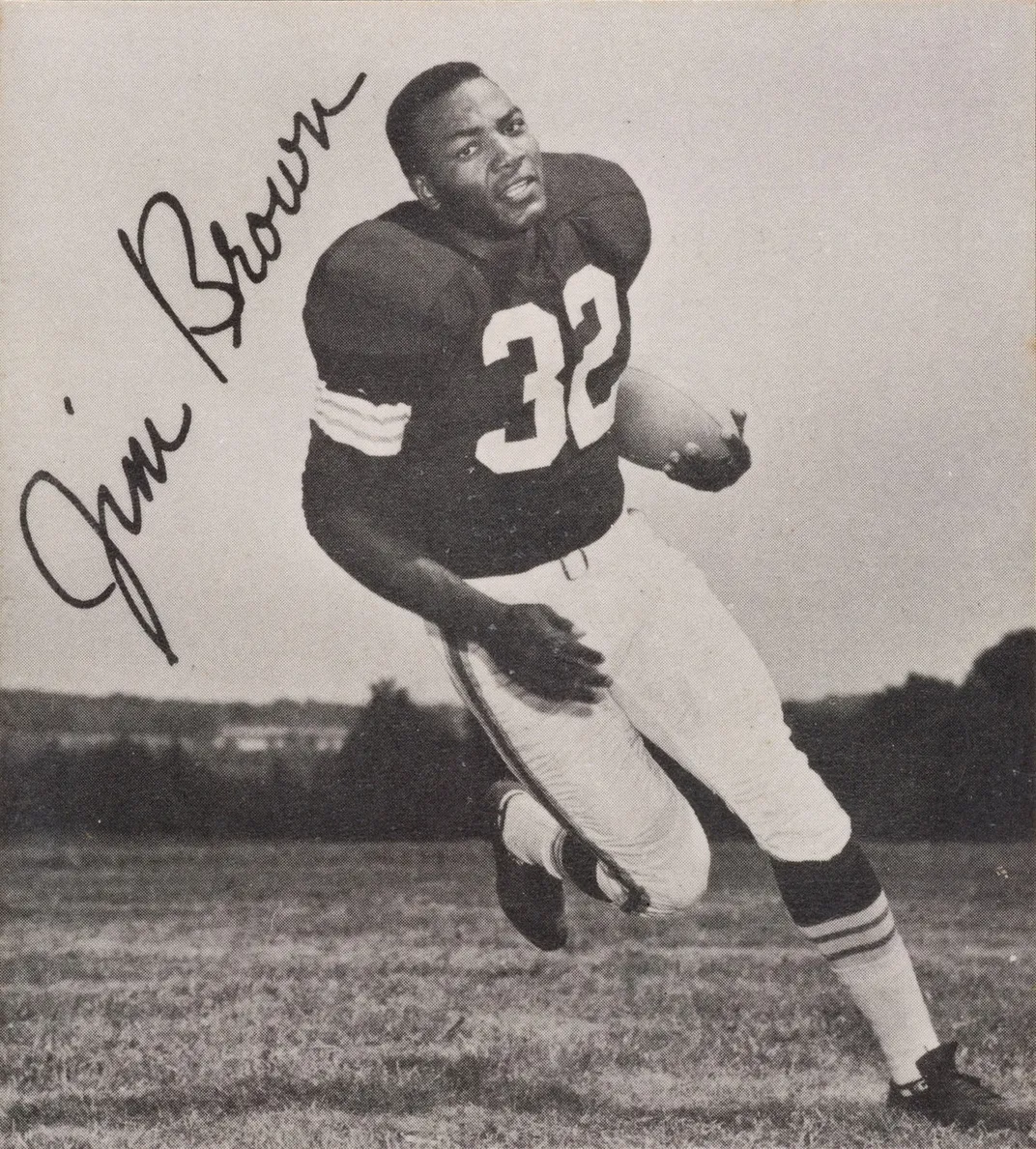

On the night that the movie is set, Brown and Cooke were arguably more “famous and powerful” than Clay and Malcolm, Powers told the Miami Herald. Then 28, Brown had been the Cleveland Browns’ star running back since 1958 and was widely heralded as one of football’s greatest players. He’d just filmed a role in the Western Rio Conchos and would soon leave the sport to pursue a career in acting.

Thirty-year-old Cooke, meanwhile, was “one of the pioneers who really brought gospel and R&B music into the mainstream” before shifting gears to chart-topping pop hits, according to Richard Walter, a curator at the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix. By 1964, the “You Send Me” singer had launched his own label, SAR Records, and established himself not only as a musician, but as an entrepreneur.

Cooke’s career trajectory “basically is the story of American music,” says Walter, “going from the Deep South up to these big urban centers, getting a bigger audience, and then dealing with questions of whose music is this? … Do I have my own community behind me? And what are the sacrifices or compromises I have based on the direction I take?”

Compared with Brown and Cooke, Malcolm’s influence, particularly within the Nation of Islam, was waning. The 38-year-old black nationalist minister had grown disillusioned with the religious movement after learning that its leader, Elijah Muhammad, had fathered several children out of wedlock; Muhammad was similarly disenchanted with Malcolm, who’d made some disparaging comments following John F. Kennedy’s November 1963 assassination and found himself barred from speaking publicly on behalf of the Nation. Despite their differences, Malcolm still hoped to regain Muhammad’s favor—a task he set out to accomplish by bringing another prominent figure into the fold.

Malcolm and Clay met in 1962, two years after the latter first made headlines by winning a gold medal at the Olympics. As Thomas explains, the young athlete had made a name for himself by telling a Soviet reporter that the United States—despite its rampant racial inequality—was “the best country in the world, including yours.” Clay’s comment “reaffirmed this idea that America was a great country, [and] we were solving our racial problems,” says Thomas. But by 1964, the man formerly known as Cassius Clay was articulating “a different vision [that] caught a number of Americans by surprise”—a shift motivated in no small part by Malcolm and the Nation of Islam.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/06/97063ae1-d68e-46d5-8f26-182671be4279/screen_shot_2021-01-15_at_102330_am.png)

What events does One Night in Miami dramatize?

On February 25, 1964, Liston, a seasoned boxer who’d won the world heavyweight champion title by knocking out Floyd Patterson during a 1962 match, was favored 7-to-1 to retain his title. But at least one observer—Malcolm—was convinced that Clay, who’d earned a reputation as a braggart with little to show for his bravado (one sports writer declared that “[t]he love of Cassius for Clay is so rapturous no girl could come between them”), would emerge victorious.

As Malcolm saw it, write Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith in Blood Brothers: The Fatal Friendship Between Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X, Clay’s victory had been preordained by Allah. With this win—and Clay’s subsequent elevation in status—the civil rights leader believed his protégé was ready to move on to what was, in his view, a more pressing calling: politics.

“Well, Brown,” Malcolm reportedly asked the football star that night, “don’t you think it’s time for this young man to stop spouting off and get serious?” Brown, for his part, also felt that Clay’s new heavyweight title “was not an end in itself [but] … a platform from which to advance far more urgent matters,” per Blood Brothers. (Brown wasn’t part of the Nation of Islam, but he was skeptical of passive resistance and nonviolent protest’s effectiveness.)

In One Night in Miami, Malcolm also makes an appeal to Cooke, castigating him “for his lack of political commitment [and] … excoriating him for courting white audiences through frivolous love songs,” as Jack Hamilton, author of Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination, notes in a scathing review for Slate that argues the characterization is unfair. These kinds of accusations are “common when you talk about African Americans in the arts,” with critics questioning whether works “should only be seen through the lens of social justice, or through the lens of art for art’s sake,” says Dwandalyn Reece, a music curator at NMAAHC. But, she adds, such arguments fail to recognize the value of differing approaches to civil rights.

“Cooke, like many other people, find[s] ways toward fighting for racial equality, … not through the lens of just protesting or being a voice on the streets or on television … but [by] opening up opportunities for other people,” Reece explains, “making sure African American voices are heard, are employed, that the music reaches a broad audience, and also opening doors as a performer.” (Movie Cooke similarly points out that his label has launched many black artists’ careers, making the case for effecting change from within an unjust system.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/63/97637584-b71a-4e3d-8c27-a8d6b5004206/1280px-malcolm_x_nywts_2a.jpg)

Troutman echoes Reece’s sentiments, saying, “[T]he mere acts of claiming public spaces with such success, of running a record company to create more space for Black voices … these were devastatingly powerful and critical weapons to wield.”

What happened to the four men after February 25, 1964?

The morning after One Night in Miami’s eponymous events, an uncharacteristically recalcitrant Clay publicly confirmed his ties to the Nation of Islam for the first time. Motivated by his newfound status as the world’s heavyweight champion, he proceeded to deliver a freewheeling meditation on the religious movement’s merits. In that speech, says Thomas, Clay also took care to distance himself from his athletic predecessors: Unlike Floyd Patterson, a former heavyweight champion who’d promoted integration, he had no plans to move into a white neighborhood. (“We believe that forced and token integration is but a temporary and not an everlasting solution,” Clay told reporters. “... It is merely a pacifier.”)

“I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” Clay added. “I’m free to be who I want.”

By identifying himself as a convert to the Nation of Islam, the boxer attracted ire from white and black Americans alike. “His stance became unpopular in white America … because he had denounced America and denounced integration,” Thomas explains. “And for African Americans, the fact that he wasn’t Christian was highly problematic.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/51/4e519013-75d1-435a-b742-91bb141f2a82/gettyimages-50333808.jpg)

As Clay grew closer to the Nation of Islam’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, in the months following the fight, his friendship with Malcolm faltered. The last time the pair saw each other was in May, when Malcolm attempted to greet his former friend, by then known as Muhammad Ali, during a visit to Ghana.

“He wants to engage with him, say hello,” Smith, co-author of Blood Brothers, told NPR in 2016. “He doesn't know Ali is mad at him, that they’re no longer friends. He’s got this half-smile on his face. And Muhammad Ali, just stone-faced, says, ‘Brother Malcolm, you shouldn’t have crossed the Honorable Elijah Muhammad.’ And he essentially walks away from him.”

Ali, who in 1975 rejected the Nation in favor of Sunni Islam—the same denomination Malcolm embraced following his departure from the movement—wrote in his 2004 autobiography that “[t]urning my back on Malcolm was one of the mistakes that I regret most in my life.” The boxer never reconciled with his former mentor. Almost exactly a year after the Clay-Liston fight, Malcolm was assassinated under still-undetermined circumstances. The civil rights icon’s autobiography, based on a series of interviews with journalist Alex Haley, was released posthumously in October 1965, ensuring, “in many ways, [that he] became much more famous in death than he was in life,” according to Thomas.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/6d/486d424b-6cfd-415f-99b8-de3f759ba7be/fd4c.jpg)

Cooke, the charismatic musician who’d watched from the sidelines as Clay knocked Liston out, preceded Malcolm in death by just two months, sustaining a fatal gunshot wound during an altercation with a Los Angeles motel manager. Though authorities ruled the shooting a justifiable homicide, questions surrounding the incident remain.

“When you hear about Sam Cooke, the popular narrative is really tied to ‘A Change Is Gonna Come,’ and there’s less public awareness about all the other things he was doing, about the trajectory of his career, his own awakening as a performer and songwriter,” says Reece. “... That’s a loss for the rest of us, not understanding what he was able to accomplish at that time, owning [his] own record company, fostering artists, songwriting, being an entrepreneur, setting up all kinds of systems to really not only extend [his] reach, but to support the work of others.”

A year after the heavyweight bout, just two of the four men featured in One Night in Miami were still alive. Later that year, Brown, then filming the movie The Dirty Dozen, officially retired from football. He spent the next several decades balancing acting with activism, Thomas notes, establishing a black economic union aimed at helping “athletes develop businesses in their community” and Amer-I-Can, an organization that aims to help formerly incarcerated individuals reenter society. Today, the 84-year-old—who has faced accusations of violent behavior toward women throughout his career—is the last surviving member of the One Night in Miami foursome.

Ali died in 2016 after a decades-long struggle with Parkinson’s disease. Banned from boxing in 1967 after refusing to serve in the Vietnam War, he returned to the ring in 1970 and went on to win two more heavyweight championships. In 1996, the organizers of the Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta chose Ali to light the flame at the Opening Ceremonies—a significant decision given the Games’ setting in the post-Jim Crow Deep South.

“To pick someone like Muhammad Ali, who 30 years earlier was one of the most hated men in America, to now becoming one of the most beloved figures in 1996, is a really important moment,” says Thomas. “And it’s a moment in which we could measure some level of racial progress.”

The curator adds, “We came to realize that he was right about the Vietnam War, and he was right about a lot of the racial injustice that took place in society. I don’t necessarily think that he changed very much. It's that society finally caught up to him. … The country changed.”

:focal(300x148:301x149)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7e/47/7e472baf-e6cd-45e7-8d16-a3ea36dcf8dc/mobile_miami.jpg)

:focal(605x291:606x292)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/c1/3ec143f8-092a-47ac-ad0c-1fb8e8a21024/social_miami.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)