The True Story of the Battle of Midway

The new film “Midway” revisits the pivotal WWII battle from the perspectives of pilots, codebreakers and naval officers on both sides of the conflict

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/45/cb45be43-9d91-431c-ae90-15797db0dda6/midway.jpg)

“At the present time we have only enough water for two weeks. Please supply us immediately,” read the message sent by American sailors stationed at Midway, a tiny atoll located roughly halfway between North America and Asia, on May 20, 1942.

The plea for help, however, was a giant ruse; the base was not, in fact, low on supplies. When Tokyo Naval Intelligence intercepted the dispatch and relayed the news onward, reporting that the “AF” air unit was in dire need of fresh water, their American counterparts finally confirmed what they had long suspected: Midway and “AF,” cited by the Japanese as the target of a major upcoming military operation, were one and the same.

This codebreaking operation afforded the United States a crucial advantage at what would be the Battle of Midway, a multi-day naval and aerial engagement fought between June 3 and 7, 1942. Widely considered a turning point in World War II’s Pacific theater, Midway found the Imperial Japanese Navy’s offensive capabilities routed after six months of success against the Americans. As Frank Blazich, lead curator of military history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, explains, the battle leveled the playing field, giving U.S. forces “breathing room and time to go on the offensive” in campaigns such as Guadalcanal.

Midway, a new movie from director Roland Emmerich, known best for disaster spectacles like The Day After Tomorrow, traces the trajectory of the early Pacific campaign from the December 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor to the Halsey-Doolittle Raid in April 1942, the Battle of the Coral Sea in May of that same year, and, finally, Midway itself.

Traditional military lore suggests a Japanese victory at Midway would have left the U.S. West Coast vulnerable to invasion, freeing the imperial fleet to strike at will. The movie’s trailer outlines this concern in apt, albeit highly dramatic, terms. Shots of Japanese pilots and their would-be American victims flash across the screen as a voiceover declares, “If we lose, then [the] Japanese own the West Coast. Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles will burn.”

The alternative to this outcome, says Admiral Chester Nimitz, played by Woody Harrelson in the film, is simple: “We need to throw a punch so they know what it feels like to be hit.”

***

According to the National WWII Museum, Japan targeted Midway in hopes of destroying the U.S. Pacific Fleet and using the atoll as a base for future military operations in the region. (Formally annexed in 1867, Midway had long been a strategic asset for the United States, and in 1940, it became a naval air base.) Although the attack on Pearl Harbor had crippled the U.S. Navy, destroying three battleships, 18 assorted vessels and 118 aircraft, the Doolittle Raid—a bombing raid on the Japanese mainland—and the Battle of the Coral Sea—a four-day naval and aerial skirmish that left the Imperial Navy’s fleet weakened ahead of the upcoming clash at Midway—showed Japan the American carrier force was, in Blazich’s words, “still a potent threat.”

Cryptanalysts and linguists led by Commander Joseph Rochefort (played by Brennan Brown in the film) broke the Japanese Navy’s main operational code in March 1942, enabling the American intelligence unit—nicknamed Station Hypo—to track the enemy’s plans for an invasion of the still-unidentified “AF.” Rochefort was convinced “AF” stood for Midway, but his superiors in Washington disagreed. To prove his suspicions, Rochefort devised the “low supplies” ruse, confirming “AF”’s identity and spurring the Navy to take decisive counter-action.

Per the Naval History and Heritage Command, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto (Etsushi Toyokawa), commander of Japan’s imperial fleet, grounded his strategy in the assumption that an attack on Midway would force the U.S. to send reinforcements from Pearl Harbor, leaving the American fleet vulnerable to a joint strike by Japanese carrier and battleship forces lying in wait.

“If successful, the plan would effectively eliminate the Pacific Fleet for at least a year,” the NHHC notes, “and provide a forward outpost from which ample warning of any future threat by the United States would come.”

Midway, in other words, was a “magnet to draw the American forces out,” says Blazich.

Japan’s plan had several fatal flaws, chief among them the fact that the U.S. was fully aware of how the invasion was supposed to unfold. As Blazich explains, “Yamamoto does all his planning on intentions of what he believes the Americans will do rather than on our capabilities”—a risky strategy made all the more damaging by the intelligence breach. The Japanese were also under the impression that the U.S.S. Yorktown, an aircraft carrier damaged at Coral Sea, was out of commission; in truth, the ship was patched up and ready for battle after just two days at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard.

Blazich emphasizes the fact that Japan’s fleet was built for offense, not defense, likening their Navy to a “boxer with a glass jaw that can throw a punch but not take a blow.” He also points out that the country’s top military officers tended to follow “tried and true” tactics rather than study and learn from previous battles.

“The Japanese,” he says, “are kind of doomed from the start.”

***

The first military engagement of the Battle of Midway took place during the afternoon of June 3, when a group of B-17 Flying Fortress bombers launched an unsuccessful air attack on what a reconnaissance pilot had identified as the main Japanese fleet. The vessels—actually a separate invasion force targeting the nearby Aleutian Islands—escaped the encounter unscathed, and the actual fleet’s location remained hidden from the Americans until the following afternoon.

In the early morning hours of June 4, Japan deployed 108 warplanes from four aircraft carriers in the vicinity: the Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu. Although the Japanese inflicted serious damage on both the responding American fighters and the U.S. base at Midway, the island’s airfield and runways remained in play. The Americans counterattacked with 41 torpedo bombers flown directly toward the four Japanese carriers.

“Those men went into this fight knowing that it was very likely they would never come home,” says Laura Lawfer Orr, a historian at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum in Norfolk, Virginia. “Their [Douglas TBD-1 Devastators] were obsolete. They had to fly incredibly slowly … [and] very close to the water. And they had torpedoes that, most of the time, did not work.”

In just minutes, Japanese ships and warplanes had shot down 35 of the 41 Devastators. As writer Tom Powers explains for the Capital Gazette, the torpedo bombers were “sitting ducks for fierce, incessant fire from shipboard batteries and the attacks of the swift, agile defending aircraft.” Despite sustaining such high losses, none of the Devastators scored a hit on the Japanese.

Ensign George Gay, a pilot in the U.S.S. Hornet’s Torpedo Squadron 8, was the sole survivor of his 30-man aircrew. According to an NHHC blog post written by Blazich in 2017, Gay (Brandon Sklenar) crash landed in the Pacific after a showdown with five Japanese fighters. “Wounded, alone and surrounded,” he endured 30 hours adrift before finally being rescued. Today, the khaki flying jacket Gay wore during his ordeal is on view in the American History Museum’s “Price of Freedom” exhibition.

Around the time of the Americans’ failed torpedo assault, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo—operating under the erroneous assumption that no U.S. carriers were in the vicinity—rearmed the Japanese air fleet, swapping the planes’ torpedoes for land bombs needed to attack the base at Midway a second time. But in the midst of rearmament, Nagumo received an alarming report: A scout plane had spotted American ships just east of the atoll.

The Japanese switched gears once again, readying torpedo bombers for an assault on the American naval units. In the ensuing confusion, sailors left unsecured ordnance, as well as fueled and armed aircraft, scattered across the four carriers’ decks.

On the American side of the fray, 32 dive bombers stationed on the Enterprise and led by Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky (Luke Evans) pursued the Japanese fleet despite running perilously low on fuel. Dick Best (Ed Skrein), commander of Bombing Squadron 6, was among the pilots participating in the mission.

Unlike torpedo bombers, who had to fly low and slow without any guarantee of scoring a hit or even delivering a working bomb, dive bombers plummeted down from heights of 20,000 feet, flying at speeds of around 275 miles per hour before aiming their bombs directly at targets.

“Dive bombing was a death defying ride of terror,” says Orr in Battle of Midway: The True Story, a new Smithsonian Channel documentary premiering Monday, November 11 at 8 p.m. “It’s basically like a game of chicken that a pilot is playing with the ocean itself. … A huge ship is going to appear about the size of a ladybug on the tip of a shoe, so it’s tiny.”

The Enterprise bombers’ first wave of attack took out the Kaga and the Akagi, both of which exploded in flames from the excess ordnance and fuel onboard. Dive bombers with the Yorktown, meanwhile, struck the Soryu, leaving the Japanese fleet with just one carrier: the Hiryu.

Close to noon, dive bombers from the Hiryu retaliated, hitting the Yorktown with three separate strikes that damaged the carrier but did not disable it. Later in the afternoon, however, a pair of torpedoes hit the partially repaired Yorktown, and at 2:55 p.m., Captain Elliott Buckmaster ordered his crew to abandon ship.

Around 3:30 p.m., American dive bombers tracked down the Hiryu and struck the vessel with at least four bombs. Rather than continuing strikes on the remainder of the Japanese fleet, Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance (Jake Weber) opted to pull back. In doing so, Blazich explains, “He preserves his own force while really destroying Japanese offensive capability.”

Over the next several days, U.S. troops continued their assault on the Japanese Navy, attacking ships including the Mikuma and Mogami cruisers and the Asashio and Arashio destroyers. By the time hostilities ended on June 7, the Japanese had lost 3,057 men, four carriers, one cruiser and hundreds of aircraft. The U.S., comparatively, lost 362 men, one carrier, one destroyer and 144 aircraft.

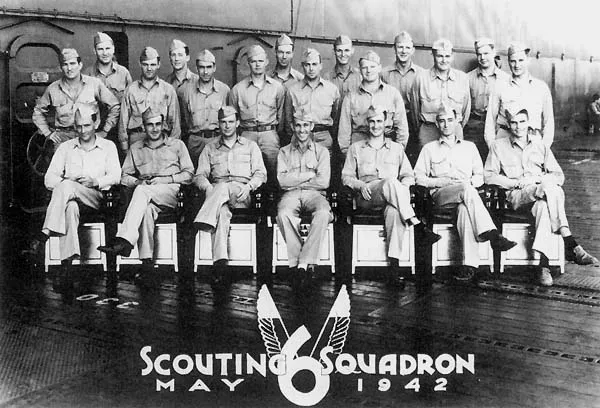

Best and Dusty Kleiss, a bomber from the Enterprise's Scouting Squadron Six, were the only pilots to score strikes on two different Japanese carriers at Midway. Kleiss—whose exploits are at the center of the Smithsonian Channel documentary—scored yet another hit on June 6, sinking the Japanese cruiser Mikuma and upping his total to three successful strikes.

George Gay, the downed torpedo bomber memorialized at the American History Museum, watched this decisive action from the water. He later recalled, “The carriers during the day resembled a very large oil-field fire. … Billowing big red flames belched out of this black smoke, ... and I was sitting in the water hollering hooray, hooray.”

***

The U.S. victory significantly curbed Japan’s offensive capabilities, paving the way for American counteroffensive strikes like the Guadalcanal Campaign in August 1942—and shifting the tide of the war strictly in the Allies’ favor.

Still, Blazich says, Midway was far from a “miracle” win ensured by plucky pilots fighting against all odds. “Midway is a really decisive battle,” the historian adds, “... an incredible victory.

But the playing field was more level than most think: While historian Gordon W. Prange’s Miracle at Midway suggests the Americans’ naval forces were “inferior numerically to the Japanese,” Blazich argues that the combined number of American aircraft based on carriers and the atoll itself actually afforded the U.S. “a degree of numerical parity, if not slight superiority,” versus the divided ranks of the Imperial Japanese Navy. (Yamamoto, fearful of revealing the strength of his forces too early in the battle, had ordered his main fleet of battleships and cruisers to trail several hundred miles behind Nagumo’s carriers.)

Naval historians Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully’s Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway deconstructs central myths surrounding the battle, including notions of Japan’s peerless strategic superiority. Crucially, Parshall and Tully write, “The imperial fleet committed a series of irretrievable strategic and operational mistakes that seem almost inexplicable. In so doing, it doomed its matchless carrier force to premature ruin.”

Luck certainly played a part in the Americans’ victory, but as Orr says in an interview, attributing the win entirely to chance “doesn’t give agency to the people who fought” at Midway. The “training and perseverance” of U.S. pilots contributed significantly, she says, as did “individual initiative,” according to Blazich. Ultimately, the Americans’ intelligence coup, the intrinsic doctrinal and philosophical weaknesses of the Imperial Japanese Navy, and factors from spur-of-the-moment decision-making to circumstance and skill all contributed to the battle’s outcome.

Orr says she hopes Midway the movie reveals the “personal side” of the battle. “History is written from the top down,” she explains, “and so you see the stories of Admiral Nimitz, [Frank Jack] Fletcher and Spruance, but you don’t always see the stories of the men themselves, the pilots and the rear seat gunners who are doing the work.”

Take, for instance, aviation machinist mate Bruno Gaido, portrayed by Nick Jonas: In February 1942, the rear gunner was promoted from third to first class after he singlehandedly saved the Enterprise from a Japanese bomber by jumping into a parked Dauntless dive bomber and aiming its machine gun at the enemy plane. During the Battle of Midway, Gaido served as a rear gunner in Scouting Squadron 6, working with pilot Frank O’Flaherty to attack the Japanese carriers. But the pair’s plane ran out of fuel, leaving Gaido and O’Flaherty stranded in the Pacific. Japanese troops later drowned both men after interrogating them for information on the U.S. fleet.

Blazich cherishes the fact that the museum has George Gay’s khaki flying jacket on display. He identifies it as one of his favorite artifacts in the collection, saying, “To the uninformed you ignore it, and to the informed, you almost venerate it [as] the amazing witness to history it is.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)