The True Story Behind “Marshall”

What really happened in the trial featured in the new biopic of future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/d0/55d05f4b-ad37-4637-97fb-664273e27e75/marshall_movie.png)

When Connecticut socialite Eleanor Strubing appeared on a highway in Westchester County, New York, soaked, battered and frantic late one night in December 1940, the story she told riveted the nation. She claimed her chauffeur had raped her four times, kidnapped her, forced her to write a ransom note for $5,000 and then thrown her off a bridge. “Mrs. J.K. Strubing Is Kidnapped and Hurled Off Bridge By Butler,” blared the New York Times on December 12, one day after the crime. Other papers referred to her assailant as the “Negro chauffeur” or “colored servant.” It was the perfect tabloid sensation—sex, money and an excuse to propagate racial stereotypes.

The only problem with Strubing’s story: it was filled with inconsistencies. The accused, a 31-year-old man named Joseph Spell, had a different version of the events of that night. Fortunate for him, his claims of innocence had a friendly ear: that of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and its head lawyer, a 32-year-old from Baltimore named Thurgood Marshall.

The story of the trial is the central narrative in Marshall, a new movie directed by Reginald Hudlin (a warning: lots of spoilers for the movie ahead). And the titular character, played by Chadwick Boseman, seems more than deserving of a Hollywood biopic, says Wil Haygood, the author of Showdown: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court Nomination That Changed America. (Haygood also wrote the Washington Post article, later turned into a book, that was the basis for 2013’s biopic The Butler).

“He was the one black lawyer in this country in the modern pre-Civil Rights era who always had the big picture in mind,” says Haygood. “He would file voting rights cases, employment rights cases, criminal justice cases, housing discrimination cases, and all of these victories became the blueprint for the 1964 Civil Rights Bill and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.”

Born in Baltimore in 1908, Marshall was the son of a steward and a kindergarten teacher. Marshall showed a talent for law from an early age, becoming a key member of his school’s debate team and memorizing the U.S. Constitution (which was actually assigned to him as punishment for misbehaving in class). Marshall attended the historically black college Lincoln University and graduated with honors in 1930 before attending Howard Law School, where he came under the guidance of civil rights lawyer Charles Houston. Upon graduating, he set to work on cases for the NAACP.

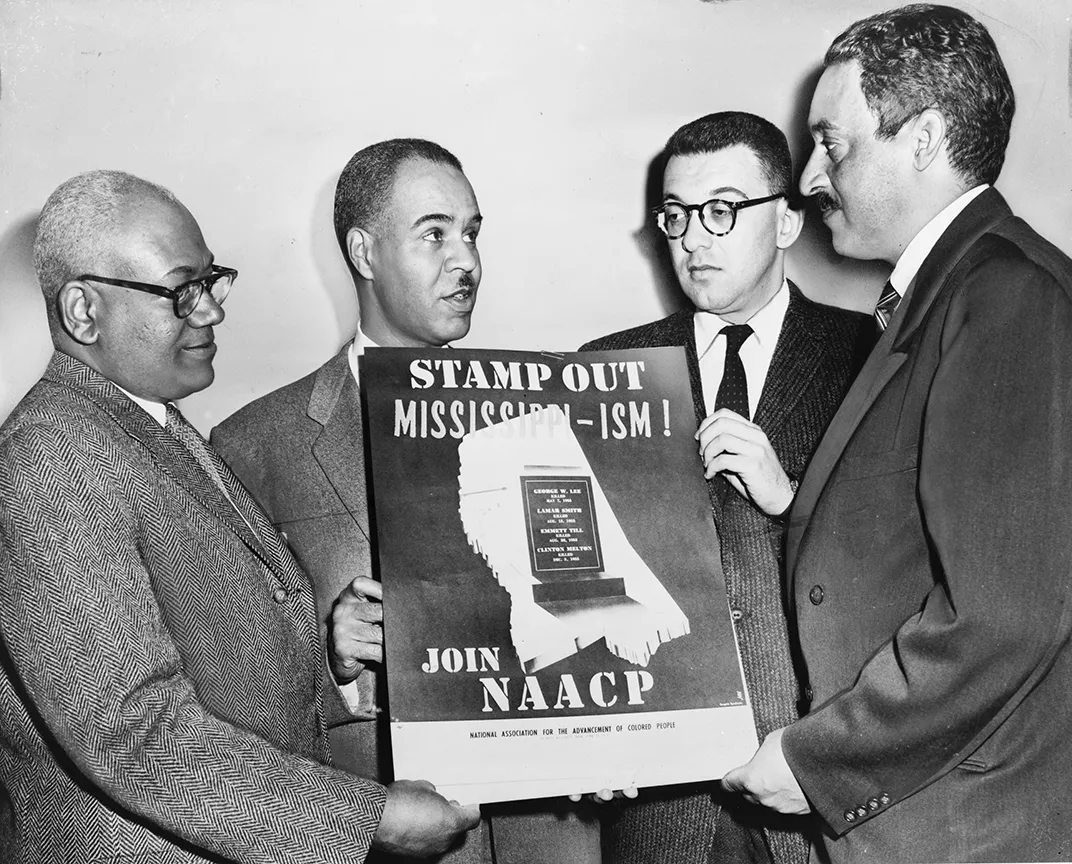

At the time of the Spell trial, Marshall was already gaining a stellar reputation as a lawyer who fought racial injustice across the country, particularly in the South (it would be another 14 years before he argued Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court, and 27 years before he became the court’s first African-American Justice). As a lawyer, Marshall helped create the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, “the first public interest law firm devoted entirely to identifying cases that would change society, not just help a particular plaintiff,” writes political scientist Peter Dreier. And while Marshall was fully invested in the more theoretically difficult cases to do with education and segregation, he was more than happy to take on clients like Joseph Spell.

First, Marshall needed a co-counselor based in Connecticut to help him argue the case, someone more familiar with the laws and politics particular to the state. The Bridgeport branch of the NAACP hired local lawyer Samuel Friedman, played in the movie by Josh Gad, even though Friedman’s initial reaction was, “I don’t think you could find a man on the street that in any way had sympathy for Spell or that believed that this was consensual, including me.” This was especially true because Spell didn’t deny he’d had sex with Strubing—he simply asserted that she had agreed to it.

At the time of the incident in question, Spell and his wife Virgis Clark, lived in the attic of the Strubing home. According to Spell’s telling, he’d knocked on Eleanor Strubing’s bedroom door one evening while her husband was away to ask if he could borrow money. When Strubing answered the door, she was wearing nothing but a silk robe and invited Spell in, telling him she’d be happy to help him. When he saw her, Spell proclaimed his interest in having an affair with her. She agreed, as long as he kept it secret, but was afraid of being discovered in the bedroom. So the two went down to the car and began having sex, until the fear of being impregnated overtook her, writes biographer Juan Williams in Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary. “We stopped [intercourse] and I had a discharge in my pocket handkerchief,” Spell told his lawyers during the deposition.

“I suggested we go for a drive,” he continued. “She said that would be all right.”

But even the drive made Strubing fearful of being found out. She told Spell to head into New York, then ordered him to pull over at the Kensico Reservoir and jumped out of the car. Spell, worried she might hurt herself if he attempted to pursue her any further, finally left. That was where two truckers found Strubing later in the evening, when she made her accusation. Spell was taken into police custody only a few hours later.

“Most black men in the South were lynched for charges of rape. They never even made it to trial,” Haygood says. He points to the Scottsboro Boys trial as one poignant example of this kind of injustice. The 1931 case revolved around nine African-American teenagers sentenced to death for raping two white women, though no evidence was ever found of that charge (most of the sentences were lowered, and some of the men had their verdicts overturned).

But the Scottsboro case was only one of a multitude. In 1923, the black Florida town of Rosewood was destroyed, its residents massacred, after a black man was accused of raping a white woman. In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was brutally murdered for allegedly flirting with a white woman. Mississippi congressman Thomas Sisson even said, “As long as rape continues, lynching will continue… We are going to protect our girls and womenfolk from these black brutes.”

As the African-American newspaper New York Star & Amsterdam News put it in the days leading up to Spell’s trial, “It was generally believed that the jury’s final verdict would be based on America’s unwritten law about white women and colored men. With white men and colored women, however, the unwritten law is usually forgotten.”

Marshall was aware of the bias he might be fighting against with a jury comprised entirely of white citizens. After all, he’d had threats made against his life for taking on such cases in the past, and would receive more of that type of threat in the Spell case. Yet even though Spell faced 30 years in prison, and was offered a plea bargain by the prosecuting attorneys, Marshall wrote to Friedman, “The more I think over the possibility … of Spell’s accepting a ‘plea’ the more I am convinced that he cannot accept any plea of any kind. It seems to me that he is not only innocent but is in a position where everyone else knows he is innocent.”

And the outcome of the Spell case didn’t just matter for the defendant as an individual, and as a continuation of racism directed against black men—it also affected local African-Americans, many of whom were employed as domestic staff. If Spell lost, they might soon have even fewer options to earn income.

Friedman and Marshall’s case rested on pointing out the many discrepancies in Strubing’s story, and the evidence that police officers failed to turn up, including a ransom note or rope that Strubing claimed to have been tied up with. When Strubing said she was gagged, and that was why she hadn’t called out, Friedman gagged himself as she described and then startled the jury with a loud shriek, writes legal historian Daniel J. Sharfstein.

When a police sergeant asked the doctor about his examination of Strubing, the doctor responded that he “didn’t find anything to take a smear of”—meaning Spell’s semen—which Marshall and Friedman used to argue that she’d had some sort of arrangement with Spell. Of course, Marshall wouldn’t have seen the case from the standpoint of a modern-day attorney; marital rape, as an example, wouldn’t be considered an offense in all 50 states until 1993, and the issue of victim-blaming, now a familiar topic of concern, was unheard of at the time.

But for all her inconsistencies, Strubing was still a society woman. Her father was an investment banker and the former governor of the Philadelphia Stock Exchange; her husband drove an ambulance in World War I and went to Princeton. Spell’s lawyers knew she was highly regarded in the community—what could the defense attorneys say that might make the jury doubt Strubing’s statements?

Friedman, knowing that Spell had been married multiple times and engaged in other extramarital affairs, decided to lean into the stereotypes of black men held by his audience, Sharfstein writes. It would be better for them to see Spell as an immoral adulterer, confirming their racist assumptions, than as a rapist, Friedman felt. In his closing argument, he said, “They had this improper relationship all through the night. [Spell] sees nothing wrong in it. The formality of marriage and divorce means nothing to him. But not to Mrs. Strubing. She has moral fiber and dignity… She knows she has done wrong.”

After both sides gave their final arguments, Judge Carl Foster had instructions of his own for the jury. “The fact that the defendant is colored and the complaining witness is a white woman should not be considered,” he told the jurors. He also added, “I charge you that even if under the circumstances Mrs. Strubing used poor judgment for her own protection, such facts in themselves do not give the accused any license to have sexual intercourse with her against her will.”

After 12 hours of deliberation, the all-white jury returned with a verdict: the acquittal of Joseph Spell.

“It was a miracle,” Haygood says. “But Thurgood Marshall trafficked in miracles.”

The case was so famous that his name appears in a letter from French novelist Carl Van Vechten to poet Langston Hughes. “Joseph Spell, just freed of a charge of rape, is in need of a job. He is basking in publicity in the Amsterdam News office and has a tremendous fan mail!” Van Vechten wrote. Eventually Spell moved to East Orange, New Jersey, where he lived with his wife until his death.

It wasn’t the last time Marshall would prove his mettle in a challenging case. He argued 32 before the Supreme Court and won 29 of them. For Haygood, it’s a real joy to see Marshall finally receiving the attention he deserves. At the time of Spell’s trial, he says, “The northern media did not do a very good job of looking in their own back yard when it came to racism and segregation. And it still happens. These code words and narratives have been around for a long, long time.”

But sometimes, as Marshall’s work proves, those narratives get toppled.

Wil Haygood will appear in conversation with Reginald Hudlin, director of “Marshall,” at the National Museum of African American History and Culture on Saturday, October 7 at 7p.m. More details about the event here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)