Catherine the Great is a monarch mired in misconception.

Derided both in her day and in modern times as a hypocritical warmonger with an unnatural sexual appetite, Catherine was a woman of contradictions whose brazen exploits have long overshadowed the accomplishments that won her “the Great” moniker in the first place.

Ruler of Russia from 1762 to 1796, Catherine championed Enlightenment ideals, expanded her empire’s borders, spearheaded judicial and administrative reforms, dabbled in vaccination, curated a vast art collection that formed the foundation of one of the world’s greatest museums, exchanged correspondence with such philosophers as Voltaire and Dennis Diderot, penned operas and children’s fairy tales, founded the country’s first state-funded school for women, drafted her own legal code, and promoted a national system of education. Perhaps most impressively, the empress—born a virtually penniless Prussian princess—wielded power for three decades despite the fact that she had no claim to the crown whatsoever.

A new Hulu series titled “The Great” takes its cue from the little-known beginnings of Catherine’s reign. Adapted from his 2008 play of the same name, the ten-part miniseries is the brainchild of screenwriter Tony McNamara. Much like how his previous film, The Favourite, reimagined the life of Britain’s Queen Anne as a bawdy “period comedy,” “The Great” revels in the absurd, veering from the historical record to gleefully present a royal drama tailor-made for modern audiences.

“I think the title card reads ‘an occasionally true story,’” McNamara tells the Sydney Morning Herald’s Michael Idato. “And yet it was important to me that there were tent poles of things that were true, [like] … her being a kid who didn't speak the language, marrying the wrong man and responding to that by deciding to change the country.”

Featuring Elle Fanning as the empress and Nicholas Hoult as her mercurial husband, Peter III, “The Great” differs from the 2019 HBO miniseries “Catherine the Great,” which starred Helen Mirren as its title character. Whereas the premium cable series traced the trajectory of Catherine’s rule from 1764 to her death, “The Great” centers on her 1762 coup and the sequence of events leading up to it. Here’s what you need to know to separate fact from fiction ahead of the series’ May 15 premiere.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/ee/29ee1253-1800-4191-b5e1-e8314ad94025/tgr_106_ou_00405rt-1.jpg)

How did Catherine the Great come to power?

To put it bluntly, Catherine was a usurper. Aided by her lover Grigory Orlov and his powerful family, she staged a coup just six months after her husband took the throne. The bloodless shift in power was so easily accomplished that Frederick the Great of Prussia later observed, “[Peter] allowed himself to be dethroned like a child being sent to bed.”

Born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, a principality in modern-day central Germany, in 1729, the czarina-to-be hailed from an impoverished Prussian family whose bargaining power stemmed from its noble connections. Thanks to these ties, she soon found herself engaged to the heir to the Russian throne: Peter, nephew of the reigning empress, Elizabeth, and grandson of another renowned Romanov, Peter the Great. Upon arriving in St. Petersburg in 1744, Sophie converted to Eastern Orthodoxy, adopted a Russian name and began learning to speak the language. The following year, the 16-year-old wed her betrothed, officially becoming Grand Duchess Catherine Alekseyevna.

Catherine and Peter were ill-matched, and their marriage was notoriously unhappy. As journalist Susan Jaques, author of The Empress of Art, explains, the couple “couldn’t have been more different in terms of their intellect [and] interests.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/05/e40599f3-5f67-4d15-89de-9155cba35e9e/empress_catherine_the_great_circa_1845_george_christoph_grooth.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/6c/396c5f90-7722-4902-8b6d-eb6f6882343a/peter_iii_and_catherine_ii_by_grooth_copy_in_odessa.jpg)

While Peter was “boorish [and] totally immature,” says historian Janet Hartley, Catherine was an erudite lover of European culture. A poor student who felt a stronger allegiance to his home country of Prussia than Russia, the heir spent much of his time indulging in various vices—and unsuccessfully working to paint himself as an effective military commander. These differences led both parties to seek intimacy elsewhere, a fact that raised questions, both at the time and in the centuries since, about the paternity of their son, the future Paul I. Catherine herself suggested in her memoirs that Paul was the child of her first lover, Sergei Saltykov.

The couple’s loveless marriage afforded Catherine ample opportunity to pursue her intellectual interests, from reading the work of Enlightenment thinkers to perfecting her grasp of Russian. “She trained herself,” biographer Virginia Rounding told Time’s Olivia B. Waxman last October, “learning and beginning to form the idea that she could do better than her husband.”

In Catherine’s own words, “Had it been my fate to have a husband whom I could love, I would never have changed towards him.” Peter, however, proved to be not only a poor life partner, but a threat to his wife’s wellbeing, particularly following his ascension to the Russian throne upon his aunt Elizabeth’s death in January 1762. As Robert K. Massie writes in Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman, “[F]rom the beginning of her husband’s reign, her position was one of isolation and humiliation. … It was obvious to her that Peter’s hostility had evolved into a determination to end their marriage and remove her from public life.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/ec/a5ec3563-a270-4727-a5ac-52e2f4b4b4e3/800px-coronation_portrait_of_peter_iii_of_russia_-1761.jpeg)

Far from resigning herself to this fate, Catherine bided her time and watched as Peter alienated key factions at court. “Though not stupid, he was totally lacking in common sense,” argues Isabel de Madariaga in Catherine the Great: A Short History. Catherine, for her part, claimed in her memoirs that “all his actions bordered on insanity.” By claiming the throne, she wrote, she had saved Russia “from the disaster that all this Prince’s moral and physical faculties promised.”

Like his wife, Peter was actually Prussian. But whereas she downplayed this background in favor of presenting herself as a Russian patriot, he catered to his home country by abandoning conquests against Prussia and pursuing a military campaign in Denmark that was of little value to Russia. Further compounding these unpopular decisions were his attempted repudiation of his wife in favor of his mistress and his seizure of church lands under the guise of secularization.

“Peter III was extremely capricious,” adds Hartley. “ … There was every chance he was going to be assassinated. I think Catherine realized that her own position and her own life [were] probably under threat, and so she acted.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/e5/dee54a76-ffd7-4cd0-aa50-6be61d112431/800px-catherine_ii_by_veriksen_1766-7_statens_museum_for_kunst_denmark.jpg)

These tensions culminated in a July 9, 1762, coup. Catherine—flanked by Orlov and her growing cadre of supporters—arrived at the Winter Palace to make her official debut as Catherine II, sole ruler of Russia. As Simon Sebag Montefiore notes in The Romanovs: 1618–1918, Peter, then on holiday in the suburbs of St. Petersburg, was “oblivious” to his wife’s actions. But when he arrived at his palace and found it abandoned, he realized what had occurred. Declaring, “Didn’t I tell you she was capable of anything?” Peter proceeded “to weep and drink and dither.”

That same morning, two of the Orlov brothers arrested Peter and forced him to sign a statement of abdication. Eight days later, the dethroned tsar was dead, killed under still-uncertain circumstances alternatively characterized as murder, the inadvertent result of a drunken brawl and a total accident. The official cause of death was advertised as “hemorrhoidal colic”—an “absurd diagnosis” that soon became a popular euphemism for assassination, according to Montefiore.

No evidence conclusively linking Catherine to her husband’s death exists, but as many historians have pointed out, his demise benefitted her immensely. Ostensibly reigning on behalf of Peter’s heir apparent—the couple’s 8-year-old son, Paul—she had no intention of yielding the throne once her son came of age. With Peter out of the picture, Catherine was able to consolidate power from a position of strength. At the same time, she recognized the damage the killing had inflicted on her legacy: “My glory is spoilt,” she reportedly said. “Posterity will never forgive me.”

What did Catherine accomplish? And what did she fail to achieve?

Contrary to Catherine’s dire prediction, Peter’s death, while casting a pall over her rule, did not completely overshadow her legacy. “Amazingly,” writes Montefiore, “the regicidal, uxoricidal German usurper recovered her reputation not just as Russian tsar and successful imperialist but also as an enlightened despot, the darling of the philosophes.”

Several years into her reign, Catherine embarked on an ambitious legal endeavor inspired by—and partially plagiarized from—the writings of leading thinkers. Called the Nakaz, or Instruction, the 1767 document outlined the empress’ vision of a progressive Russian nation, even touching on the heady issue of abolishing serfdom. If all went as planned, according to Massie, the proposed legal code would “raise the levels of government administration, of justice, and of tolerance within her empire.” But these changes failed to materialize, and Catherine’s suggestions remained just that.

Though Russia never officially adopted the Nakaz, the widely distributed 526-article treatise still managed to cement the empress’ reputation as an enlightened European ruler. Her many military campaigns, on the other hand, represent a less palatable aspect of her legacy. Writing for History Extra, Hartley describes Catherine’s Russia as an undoubtedly “aggressive nation” that clashed with the Ottomans, Sweden, Poland, Lithuania and the Crimea in pursuit of additional territory for an already vast empire. In terms of making Russia a “great power,” says Hartley, these efforts proved successful. But in a purely humanitarian light, Catherine’s expansionist drive came at a great cost to the conquered nations and the czarina’s own country alike.

In 1774, a disillusioned military officer named Yemelyan Pugachev capitalized on the unrest fomented by Russia’s ongoing fight with Turkey to lead hundreds of thousands into rebellion. Uniting Cossacks, peasants, escaped serfs and “other discontented tribal groups and malcontents, Pugachev produced a storm of violence that swept across the steppes,” writes Massie. Catherine was eventually able to put down the uprising, but the carnage exacted on both sides was substantial.

On a personal level, Pugachev’s success “challenged many of Catherine’s Enlightenment beliefs, leaving her with memories that haunted her for the rest of her life,” according to Massie. While the deeply entrenched system of Russian serfdom—in which peasants were enslaved by and freely traded among feudal lords—was at odds with her philosophical values, Catherine recognized that her main base of support was the nobility, which derived its wealth from feudalism and was therefore unlikely to take kindly to these laborers’ emancipation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/f6/b8f6e954-2744-4425-8063-880e080ba86b/hermitage_raphael_loggias_04.jpg)

Catherine’s failure to abolish feudalism is often cited as justification for characterizing her as a hypocritical, albeit enlightened, despot. Though Hartley acknowledges that serfdom is “a scar on Russia,” she emphasizes the practical obstacles the empress faced in enacting such a far-reaching reform, adding, “Where [Catherine] could do things, she did do things.”

Serfdom endured long beyond Catherine’s reign, only ending in 1861 with Alexander II’s Emancipation Manifesto. While the measure appeared to be progressive on paper, the reality of the situation remained stark for most peasants, and in 1881, revolutionaries assassinated the increasingly reactionary czar—a clear example of what Hartley deems “autocracy tempered by assassination,” or the idea that a ruler had “almost unlimited powers but was always vulnerable to being dethroned if he or she alienated the elites.”

After Pugachev’s uprising, Catherine shifted focus to what Massie describes as more readily achievable aims: namely, the “expansion of her empire and the enrichment of its culture.”

Catherine’s contributions to Russia’s cultural landscape were far more successful than her failed socioeconomic reforms. Jaques says that Catherine initially started collecting art as a “political calculation” aimed at legitimizing her status as a Westernized monarch. Along the way, she became a “very passionate, knowledgeable” proponent of painting, sculpture, books, architecture, opera, theater and literature. A self-described “glutton for art,” the empress strategically purchased paintings in bulk, acquiring as much in 34 years as other royals took generations to amass. This enormous collection ultimately formed the basis of the Hermitage Museum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/6d/196de70e-f841-4875-bc26-e6cb3e0485d6/1024px-the_bronze_horseman_st_petersburg_russia.jpg)

In addition to collecting art, Catherine commissioned an array of new cultural projects, including an imposing bronze monument to Peter the Great, Russia’s first state library, exact replicas of Raphael’s Vatican City loggias and palatial neoclassical buildings constructed across St. Petersburg.

The empress played a direct role in many of these initiatives. “It’s surprising that someone who’s waging war with the Ottoman Empire and partitioning Poland and annexing the Crimea has time to make sketches for one of her palaces, but she was very hands on,” says Jaques. Today, the author adds, “We’d call her a micromanager.”

Is there any truth to the myths surrounding Catherine?

To the general public, Catherine is perhaps best known for conducting a string of salacious love affairs. But while the empress did have her fair share of lovers—12 to be exact—she was not the sexual deviant of popular lore. Writing in The Romanovs, Montefiore characterizes Catherine as “an obsessional serial monogamist who adored sharing card games in her cozy apartments and discussing her literary and artistic interests with her beloved.” Many sordid tales of her sexuality can, in fact, be attributed to detractors who hoped to weaken her hold on power.

Army officer Grigory Potemkin was arguably the greatest love of Catherine’s life, though her relationship with Grigory Orlov, who helped the empress overthrow Peter III, technically lasted longer. The pair met on the day of Catherine’s 1762 coup but only became lovers in 1774. United by a shared appreciation of learning and larger-than-life theatrics, they “were human furnaces who demanded an endless supply of praise, love and attention in private, and glory and power in public,” according to Montefiore.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/a2/07a2c738-04d8-40c4-9af2-5aa0b28d6297/lovers.png)

Letters exchanged by the couple testify to the ardent nature of their relationship: In one missive, Catherine declared, “I LOVE YOU SO MUCH, you are so handsome, clever, jovial and funny; when I am with you I attach no importance to the world. I have never been so happy.” Such all-consuming passion proved unsustainable—but while the pair’s romantic partnership faded after just two years, they remained on such good terms that Potemkin continued to wield enormous political influence, acting as “tsar in all but name,” one observer noted. Upon Potemkin’s death in 1791, Catherine reportedly spent days overwhelmed by “tears and despair.”

In her later years, Catherine became involved with a number of significantly younger lovers—a fact her critics were quick to latch onto despite the countless male monarchs who did the same without attracting their subjects’ ire. Always in search of romantic intimacy, she once admitted, “The trouble is that my heart is loath to remain even one hour without love.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/0c/9e0cffa4-ae18-4e16-953d-ca76805048fa/portrait_of_empress_catherine_iia.jpg)

For all her show of sensuality, Catherine was actually rather “prudish,” says Jaques. She disapproved of off-color jokes and nudity in art falling outside of mythological or allegorical themes. Other aspects of the empress’ personality were similarly at odds: Extravagant in most worldly endeavors, she had little interest in food and often hosted banquets that left guests wanting for more. And though Catherine is characterized by modern viewers as “very flighty and superficial,” Hartley notes that she was a “genuine bluestocking,” waking up at 5 or 6 a.m. each morning, brewing her own pot of coffee to avoid troubling her servants, and sitting down to begin the day’s work.

Perhaps the most readily recognizable anecdote related to Catherine centers on a horse. But the actual story of the monarch’s death is far simpler: On November 16, 1796, the 67-year-old empress suffered a stroke and fell into a coma. She died the next day, leaving her estranged son, Paul I, as Russia’s next ruler.

McNamara tells the Sydney Morning Herald that this apocryphal anecdote helped inspire “The Great.”

“It seemed like her life had been reduced to a salacious headline about having sex with a horse,” the writer says. “Yet she’d done an enormous amount of amazing things, had been a kid who’d come to a country that wasn’t her own and taken it over.”

Publicly, Catherine evinced an air of charm, wit and self-deprecation. In private, says Jaques, she balanced a constant craving for affection with a ruthless determination to paint Russia as a truly European country.

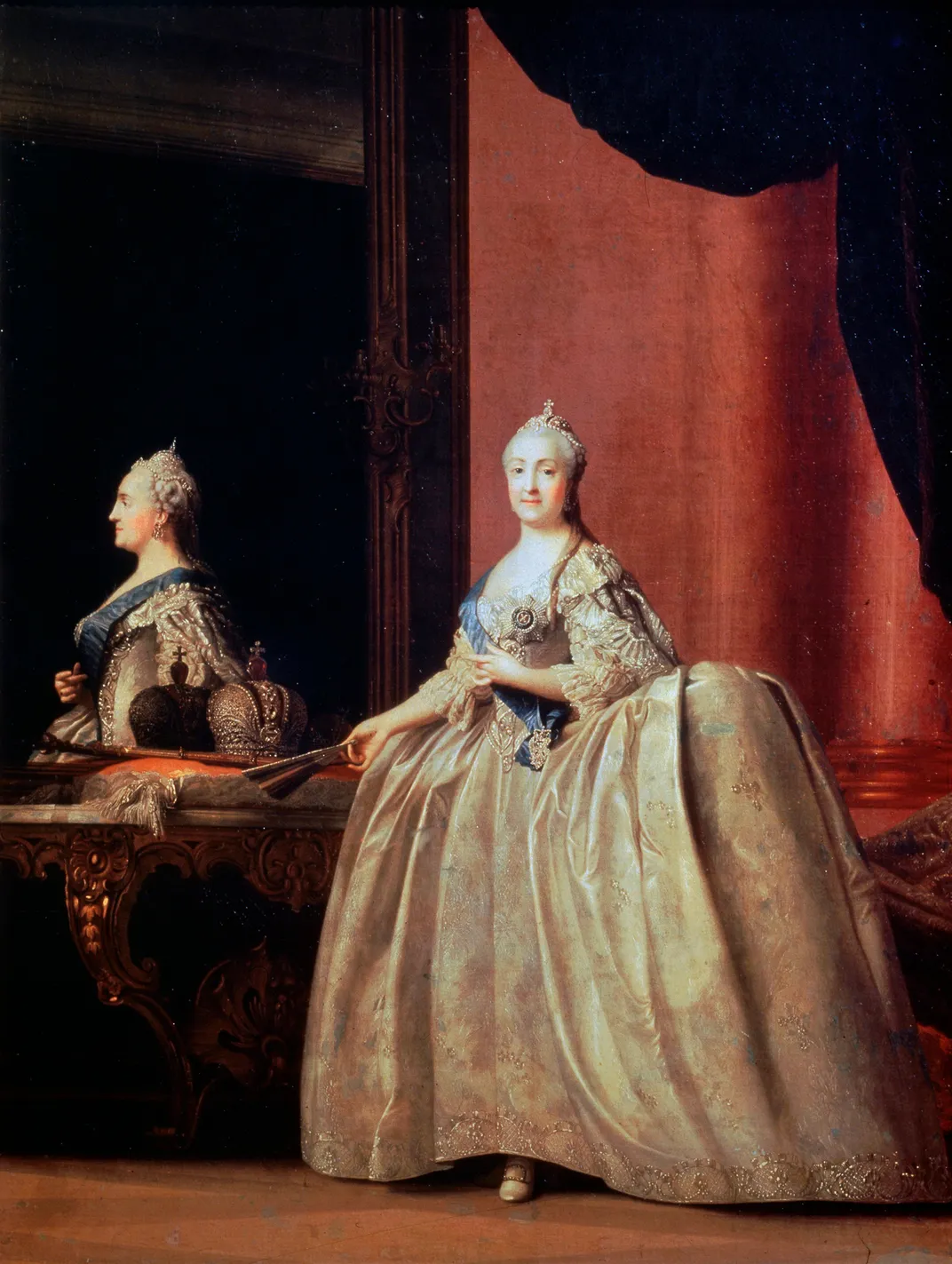

Jaques cites a Vigilius Ericksen portrait of the empress as emblematic of Catherine’s many contradictions. In the painting, she presents her public persona, standing in front of a mirror while draped in an ornate gown and serene smile. Look at the mirror, however, and an entirely different ruler appears: “Her reflection is this private, determined, ambitious Catherine,” says Jaques. “ … In one portrait, he’s managed to just somehow portray both sides of this compelling leader.”

:focal(314x108:315x109)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/76/2f76f5d7-ae55-4982-a62a-6c3f03f040b6/ctg_mobile.png)

:focal(622x154:623x155)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/4b/094b48c8-c3f5-42e3-86f3-a5b260975f41/ctgsocial.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)