The True Story of the ‘Free State of Jones’

A new Hollywood movie looks at the tale of the Mississippi farmer who led a revolt against the Confederacy

With two rat terriers trotting at his heels, and a long wooden staff in his hand, J.R. Gavin leads me through the woods to one of the old swamp hide-outs. A tall white man with a deep Southern drawl, Gavin has a stern presence, gracious manners and intense brooding eyes. At first I mistook him for a preacher, but he’s a retired electronic engineer who writes self-published novels about the rapture and apocalypse. One of them is titled Sal Batree, after the place he wants to show me.

I’m here in Jones County, Mississippi, to breathe in the historical vapors left by Newton Knight, a poor white farmer who led an extraordinary rebellion during the Civil War. With a company of like-minded white men in southeast Mississippi, he did what many Southerners now regard as unthinkable. He waged guerrilla war against the Confederacy and declared loyalty to the Union.

In the spring of 1864, the Knight Company overthrew the Confederate authorities in Jones County and raised the United States flag over the county courthouse in Ellisville. The county was known as the Free State of Jones, and some say it actually seceded from the Confederacy. This little-known, counterintuitive episode in American history has now been brought to the screen in Free State of Jones, directed by Gary Ross (Seabiscuit, The Hunger Games) and starring a grimy, scruffed-up Matthew McConaughey as Newton Knight.

Knight and his men, says Gavin, hooking away an enormous spider web with his staff and warning me to be careful of snakes, “had a number of different hide-outs. The old folks call this one Sal Batree. Sal was the name of Newt’s shotgun, and originally it was Sal’s Battery, but it got corrupted over the years.”

We reach a small promontory surrounded on three sides by a swampy, beaver-dammed lake, and concealed by 12-foot-high cattails and reeds. “I can’t be certain, but a 90-year-old man named Odell Holyfield told me this was the place,” says Gavin. “He said they had a gate in the reeds that a man on horseback could ride through. He said they had a password, and if you got it wrong, they’d kill you. I don’t know how much of that is true, but one of these days I’ll come here with a metal detector and see what I can find.”

We make our way around the lakeshore, passing beaver-gnawed tree stumps and snaky-looking thickets. Reaching higher ground, Gavin points across the swamp to various local landmarks. Then he plants his staff on the ground and turns to face me directly.

“Now I’m going to say something that might offend you,” he begins, and proceeds to do just that, by referring in racist terms to “Newt’s descendants” in nearby Soso, saying some of them are so light-skinned “you look at them and you just don’t know.”

I stand there writing it down and thinking about William Faulkner, whose novels are strewn with characters who look white but are deemed black by Mississippi’s fanatical obsession with the one-drop rule. And not for the first time in Jones County, where arguments still rage about a man born 179 years ago, I recall Faulkner’s famous axiom about history: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

After the Civil War, Knight took up with his grandfather’s former slave Rachel; they had five children together. Knight also fathered nine children with his white wife, Serena, and the two families lived in different houses on the same 160-acre farm. After he and Serena separated—they never divorced—Newt Knight caused a scandal that still reverberates by entering a common-law marriage with Rachel and proudly claiming their mixed-race children.

The Knight Negroes, as these children were known, were shunned by whites and blacks alike. Unable to find marriage partners in the community, they started marrying their white cousins instead, with Newt’s encouragement. (Newt’s son Mat, for instance, married one of Rachel’s daughters by another man, and Newt’s daughter Molly married one of Rachel’s sons by another man.) An interracial community began to form near the small town of Soso, and continued to marry within itself.

“They keep to themselves over there,” says Gavin, striding back toward his house, where supplies of canned food and muscadine wine are stored up for the onset of Armageddon. “A lot of people find it easier to forgive Newt for fighting Confederates than mixing blood.”

**********

I came to Jones County having read some good books about its history, and knowing very little about its present-day reality. It was reputed to be fiercely racist and conservative, even by Mississippi standards, and it had been a hotbed for the Ku Klux Klan. But Mississippi is nothing if not layered and contradictory, and this small, rural county has also produced some wonderful creative and artistic talents, including Parker Posey, the indie-film queen, the novelist Jonathan Odell, the pop singer and gay astronaut Lance Bass, and Mark Landis, the schizophrenic art forger and prankster, who donated fraudulent masterpieces to major American art museums for nearly 30 years before he was caught.

Driving toward the Jones County line, I passed a sign to Hot Coffee—a town, not a beverage—and drove on through rolling cattle pastures and short, new-growth pine trees. There were isolated farmhouses and prim little country churches, and occasional dilapidated trailers with dismembered automobiles in the front yard. In Newt Knight’s day, all this was a primeval forest of enormous longleaf pines so thick around the base that three or four men could circle their arms around them. This part of Mississippi was dubbed the Piney Woods, known for its poverty and lack of prospects. The big trees were an ordeal to clear, the sandy soil was ill-suited for growing cotton, and the bottomlands were choked with swamps and thickets.

There was some very modest cotton production in the area, and a small slaveholding elite that included Newt Knight’s grandfather, but Jones County had fewer slaves than any other county in Mississippi, only 12 percent of its population. This, more than anything, explains its widespread disloyalty to the Confederacy, but there was also a surly, clannish independent spirit, and in Newt Knight, an extraordinarily steadfast and skillful leader.

On the county line, I was half-expecting a sign reading “Welcome to the Free State of Jones” or “Home of Newton Knight,” but the Confederacy is now revered by some whites in the area, and the chamber of commerce had opted for a less controversial slogan: “Now This Is Living!” Most of Jones County is rural, low- or modest-income; roughly 70 percent of the population is white. I drove past many small chicken farms, a large modern factory making transformers and computers, and innumerable Baptist churches. Laurel, the biggest town, stands apart. Known as the City Beautiful, it was created by Midwestern timber barons who razed the longleaf pine forests and built themselves elegant homes on oak-lined streets and the gorgeous world-class Lauren Rogers Museum of Art.

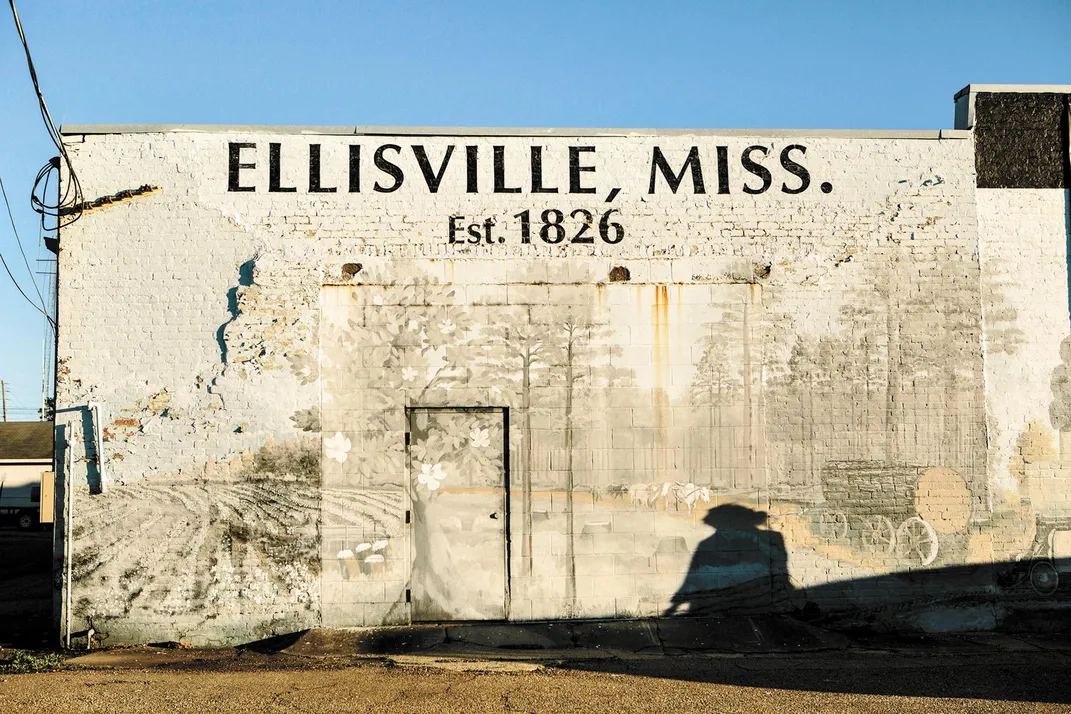

The old county seat, and ground zero for the Free State of Jones, is Ellisville, now a pleasant, leafy town of 4,500 people. Downtown has some old brick buildings with wrought-iron balconies. The grand old columned courthouse has a Confederate monument next to it, and no mention of the anti-Confederate rebellion that took place here. Modern Ellisville is dominated by the sprawling campus of Jones County Junior College, where a semiretired history professor named Wyatt Moulds was waiting for me in the entrance hall. A direct descendant of Newt Knight’s grandfather, he was heavily involved in researching the film and ensuring its historical accuracy.

A large, friendly, charismatic man with unruly side-parted hair, he was wearing alligator-skin cowboy boots and a fishing shirt. “I’m one of the few liberals you’re going to meet here, but I’m a Piney Woods liberal,” he said. “I voted for Obama, I hunt and I love guns. It’s part of the culture here. Even the liberals carry handguns.”

He described Jones County as the most conservative place in Mississippi, but he noted that race relations were improving and that you could see it clearly in the changing attitudes toward Newt Knight. “It’s generational,” he said. “A lot of older people see Newt as a traitor and a reprobate, and they don’t understand why anyone would want to make a movie about him. If you point out that Newt distributed food to starving people, and was known as the Robin Hood of the Piney Woods, they’ll tell you he married a black, like that trumps everything. And they won’t use the word ‘black.’”

His current crop of students, on the other hand, are “fired up” about Newt and the movie. “Blacks and whites date each other in high school now, and they don’t think it’s a big deal,” said Moulds. “That’s a huge change. Some of the young guys are really identifying with Newt now, as a symbol of Jones County pride. It doesn’t hurt that he was such a badass.”

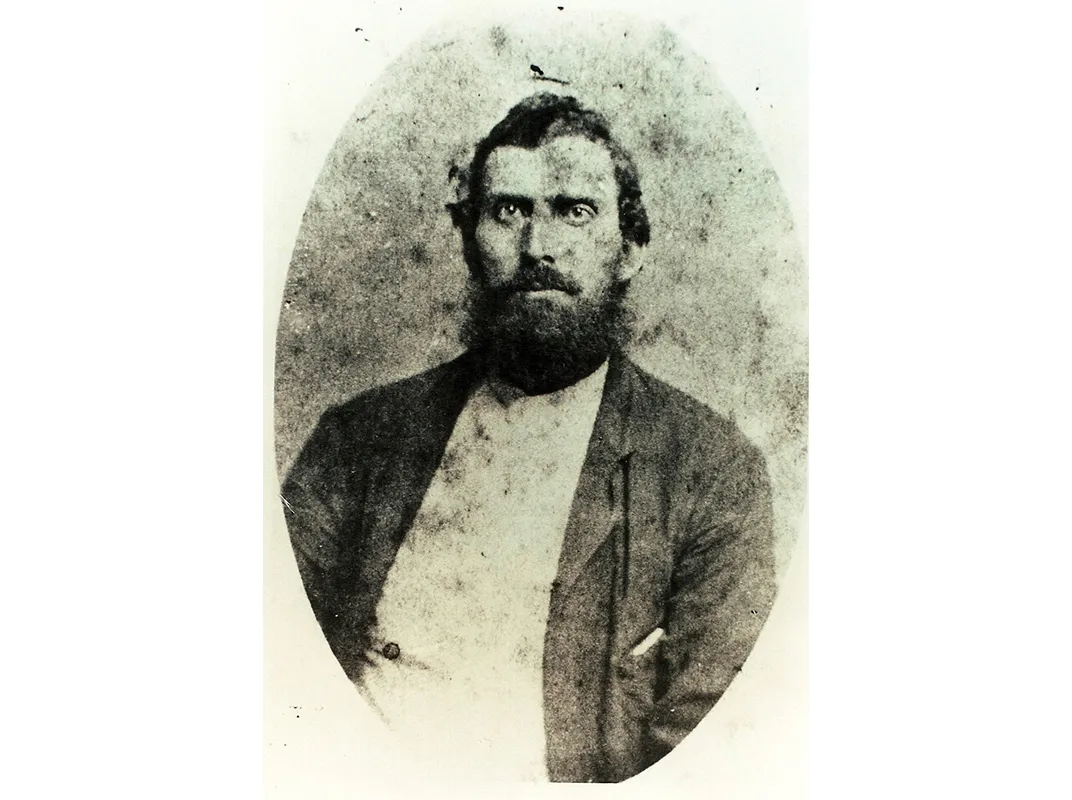

Knight was 6-foot-4 with black curly hair and a full beard—“big heavyset man, quick as a cat,” as one of his friends described him. He was a nightmarish opponent in a backwoods wrestling match, and one of the great unsung guerrilla fighters in American history. So many men tried so hard to kill him that perhaps his most remarkable achievement was to reach old age.

“He was a Primitive Baptist who didn’t drink, didn’t cuss, doted on children and could reload and fire a double-barreled, muzzle-loading shotgun faster than anyone else around,” said Moulds. “Even as an old man, if someone rubbed him the wrong way, he’d have a knife at their throat in a heartbeat. A lot of people will tell you that Newt was just a renegade, out for himself, but there’s good evidence that he was a man of strong principles who was against secession, against slavery and pro-Union.”

Those views were not unusual in Jones County. Newt’s right-hand man, Jasper Collins, came from a big family of staunch Mississippi Unionists. He later named his son Ulysses Sherman Collins, after his two favorite Yankee generals, Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman. “Down here, that’s like naming your son Adolf Hitler Collins,” said Moulds.

When secession fever swept across the South in 1860, Jones County was largely immune to it. Its secessionist candidate received only 24 votes, while the “cooperationist” candidate, John H. Powell, received 374. When Powell got to the secession convention in Jackson, however, he lost his nerve and voted to secede along with almost everyone else. Powell stayed away from Jones County for a while after that, and he was burned in effigy in Ellisville.

“In the Lost Cause mythology, the South was united, and secession had nothing to do with slavery,” said Moulds. “What happened in Jones County puts the lie to that, so the Lost Causers have to paint Newt as a common outlaw, and above all else, deny all traces of Unionism. With the movie coming out, they’re at it harder than ever.”

**********

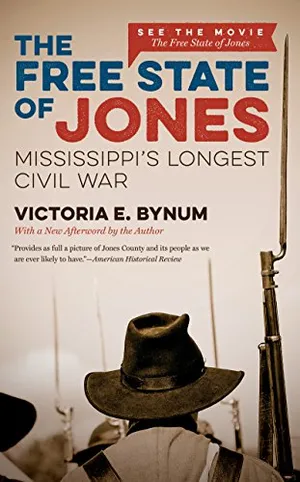

Although he was against secession, Knight voluntarily enlisted in the Confederate Army once the war began. We can only speculate about his reasons. He kept no diary and gave only one interview near the end of his life, to a New Orleans journalist named Meigs Frost. Knight said he’d enlisted with a group of local men to avoid being conscripted and then split up into different companies. But the leading scholar of the Knight-led rebellion, Victoria Bynum, author of The Free State of Jones, points out that Knight had enlisted, under no threat of conscription, a few months after the war began, in July 1861. She thinks he relished being a soldier.

In October 1862, after the Confederate defeat at Corinth, Knight and many other Piney Woods men deserted from the Seventh Battalion of Mississippi Infantry. It wasn’t just the starvation rations, arrogant harebrained leadership and appalling carnage. They were disgusted and angry about the recently passed “Twenty Negro Law,” which exempted one white male for every 20 slaves owned on a plantation, from serving in the Confederate Army. Jasper Collins echoed many non-slaveholders across the South when he said, “This law...makes it a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

Returning home, they found their wives struggling to keep up the farms and feed the children. Even more aggravating, the Confederate authorities had imposed an abusive, corrupt “tax in kind” system, by which they took what they wanted for the war effort— horses, hogs, chickens, corn, meat from the smokehouses, homespun cloth. A Confederate colonel named William N. Brown reported that corrupt tax officials had “done more to demoralize Jones County than the whole Yankee Army.”

In early 1863, Knight was captured for desertion and possibly tortured. Some scholars think he was pressed back into service for the Siege of Vicksburg, but there’s no solid evidence that he was there. After Vicksburg fell, in July 1863, there was a mass exodus of deserters from the Confederate Army, including many from Jones and the surrounding counties. The following month, Confederate Maj. Amos McLemore arrived in Ellisville and began hunting them down with soldiers and hounds. By October, he had captured more than 100 deserters, and exchanged threatening messages with Newt Knight, who was back on his ruined farm on the Jasper County border.

On the night of October 5, Major McLemore was staying at his friend Amos Deason’s mansion in Ellisville, when someone—almost certainly Newt Knight—burst in and shot him to death. Soon afterward, there was a mass meeting of deserters from four Piney Woods counties. They organized themselves into a company called the Jones County Scouts and unanimously elected Knight as their captain. They vowed to resist capture, defy tax collectors, defend each other’s homes and farms, and do what they could to aid the Union.

Neo-Confederate historians have denied the Scouts’ loyalty to the Union up and down, but it was accepted by local Confederates at the time. “They were Union soldiers from principle,” Maj. Joel E. Welborn, their former commanding officer in the Seventh Mississippi, later recalled. “They were making an effort to be mustered into the U.S. Service.” Indeed, several of the Jones County Scouts later succeeded in joining the Union Army in New Orleans.

In March 1864, Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk informed Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, that Jones County was in “open rebellion” and that guerrilla fighters were “proclaiming themselves ‘Southern Yankees.’” They had crippled the tax collection system, seized and redistributed Confederate supplies, and killed and driven out Confederate officials and loyalists, not just in Jones County but all over southeast Mississippi. Confederate Capt. Wirt Thompson reported that they were now a thousand strong and flying the U.S. flag over the Jones County courthouse—“they boast of fighting for the Union,” he added.

That spring was the high-water mark of the rebellion against the Rebels. Polk ordered two battle-hardened regiments into southeast Mississippi, under the command of Piney Woods native Col. Robert Lowry. With hanging ropes and packs of vicious, manhunting dogs, they subdued the surrounding counties and then moved into the Free State of Jones. Several of the Knight company were mangled by the dogs, and at least ten were hanged, but Lowry couldn’t catch Knight or the core group. They were deep in the swamps, being supplied with food and information by local sympathizers and slaves, most notably Rachel.

After Lowry left, proclaiming victory, Knight and his men emerged from their hide-outs, and once again, began threatening Confederate officials and agents, burning bridges and destroying railroads to thwart the Rebel Army, and raiding food supplies intended for the troops. They fought their last skirmish at Sal’s Battery, also spelled Sallsbattery, on January 10, 1865, fighting off a combined force of cavalry and infantry. Three months later, the Confederacy fell.

**********

In 2006, the filmmaker Gary Ross was at Universal Studios, discussing possible projects, when a development executive gave him a brief, one-page treatment about Newton Knight and the Free State of Jones. Ross was instantly intrigued, both by the character and the revelation of Unionism in Mississippi, the most deeply Southern state of all.

“It led me on a deep dive to understand more and more about him and the fact that the South wasn’t monolithic during the Civil War,” says Ross, speaking on the phone from New York. “I didn’t realize it was going to be two years of research before I began writing the screenplay.”

The first thing he did was take a canoe trip down the Leaf River, to get a feel for the area. Then he started reading, beginning with the five (now six) books about Newton Knight. That led into broader reading about other pockets of Unionism in the South. Then he started into Reconstruction.

“I’m not a fast reader, nor am I an academic,” he says, “although I guess I’ve become an amateur one.” He apprenticed himself to some of the leading authorities in the field, including Harvard’s John Stauffer and Steven Hahn at the University of Pennsylvania. (At the urging of Ross, Stauffer and co-author Sally Jenkins published their own book on the Jones County rebellion, in 2009.) Ross talks about these scholars in a tone of worship and adulation, as if they’re rock stars or movie stars—and none more so than Eric Foner at Columbia, the dean of Reconstruction experts.

“He is like a god, and I went into his office, and I said, ‘My name’s Gary Ross, I did Seabiscuit.’ I asked him a bunch of questions about Reconstruction, and all he did was give me a reading list. He was giving me no quarter. I’m some Hollywood guy, you know, and he wanted to see if I could do the work.”

Ross worked his way slowly and carefully through the books, and went back with more questions. Foner answered none of them, just gave him another reading list. Ross read those books too, and went back again with burning questions. This time Foner actually looked at him and said, “Not bad. You ought to think about studying this.”

“It was the greatest compliment a person could have given me,” says Ross. “I remember walking out of his office, across the steps of Columbia library, almost buoyant. It was such a heady experience to learn for learning’s sake, for the first time, rather than to generate a screenplay. I’m still reading history books all the time. I tell people this movie is my academic midlife crisis.”

In Hollywood, he says, the executives were extremely supportive of his research, and the script that he finally wrestled out of it, but they balked at financing the film. “This was before Lincoln and 12 Years a Slave, and it was very hard to get this sort of a drama made. So I went and did Hunger Games, but always keeping an eye on this. ”

Matthew McConaughey thought the Free State of Jones script was the most exciting Civil War story he had ever read, and knew immediately that he wanted to play Newt Knight. In Knight’s defiance of both the Confederate Army and the deepest taboos of Southern culture McConaughey sees an uncompromising and deeply moral leader. He was “a man who lived by the Bible and the barrel of a shotgun,” McConaughey says in an email. “If someone—no matter what their color—was being mistreated or being used, if a poor person was being used by someone to get rich, that was a simple wrong that needed to be righted in Newt’s eyes....He did so deliberately, and to the hell with the consequences.” McConaughey sums him up as a “shining light through the middle of this country’s bloodiest fight. I really kind of marveled at him.”

The third act of the film takes place in Mississippi after the Civil War. There was a phase during early Reconstruction when blacks could vote, and black officials were elected for the first time. Then former Confederates violently took back control of the state and implemented a kind of second slavery for African-Americans. Once again disenfranchised, and terrorized by the Klan, they were exploited through sharecropping and legally segregated. “The third act is what makes this story feel so alive,” says McConaughey. “It makes it relevant today. Reconstruction is a verb that’s ongoing.”

Ross thinks Knight’s character and beliefs are most clearly revealed by his actions after the war. He was hired by the Reconstruction government to free black children from white masters who were refusing to emancipate them. “In 1875, he accepts a commission in what was essentially an all-black regiment,” says Ross. “His job was to defend the rights of freed African-Americans in one of Mississippi’s bloodiest elections. His commitment to these issues never waned.” In 1876, Knight deeded 160 acres of land to Rachel, making her one of very few African-American landowners in Mississippi at that time.

Much as Ross wanted to shoot the movie in Jones County, there were irresistible tax incentives to film across the border in Louisiana, and some breathtaking cypress swamps where various cast members were infested with the tiny mites known as chiggers. Nevertheless, Ross and McConaughey spent a lot of time in Jones County, persuading many county residents to appear in the film.

“I love the Leaf River and the whole area,” says Ross. “And I’ve grown to love Mississippi absolutely. It’s a very interesting, real and complicated place.”

**********

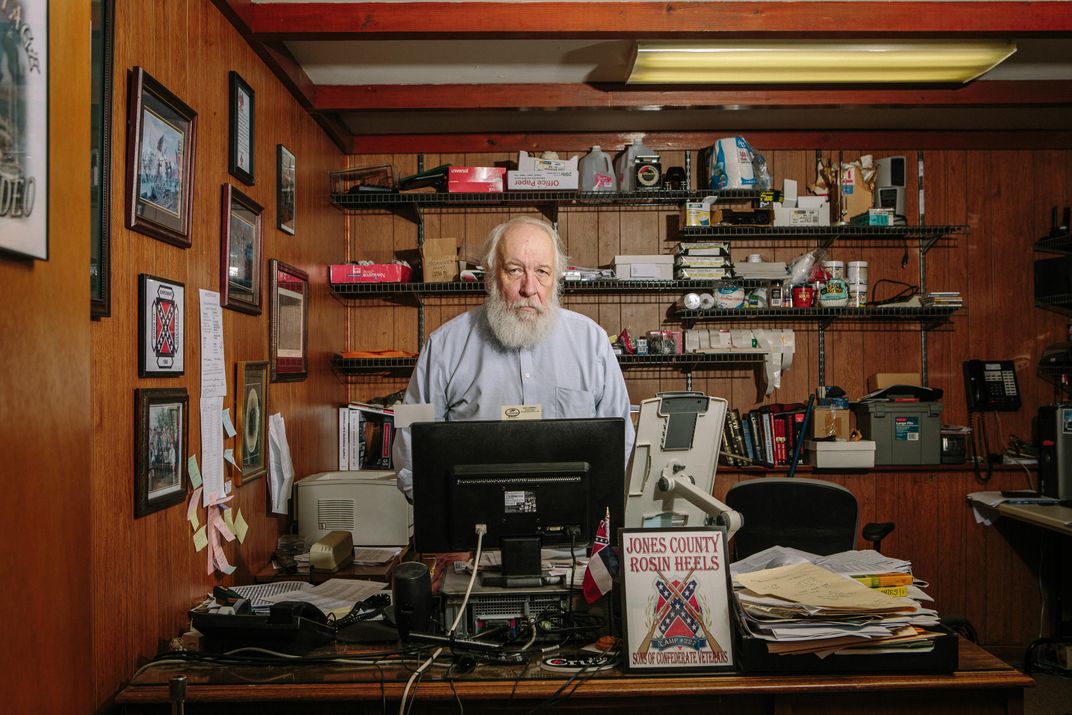

On the website of Jones County Rosin Heels, the local chapter of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, an announcement warned that the film will portray Newt Knight as a civil rights activist and a hero. Then the writer inadvertently slips into the present tense: “He is actually a thief, murderer, adulterer and a deserter.”

Doug Jefcoate was listed as camp commander. I found him listed as a veterinarian in Laurel, and called up, saying I was interested in his opinions on Newt Knight. He sounded slightly impatient, then said, “OK, I’m a history guy and a fourth-generation guy. Come to the animal hospital tomorrow.”

The receptionist led me into a small examining room and closed both its doors. I stood there for a few long minutes, with a shiny steel table and, on the wall, a Bible quotation. Then Jefcoate walked in, a middle-aged man with sandy hair, glasses and a faraway smile. He was carrying two huge, leather-bound volumes of his family genealogy.

He gave me ten minutes on his family tree, and when I interrupted to ask about the Rosin Heels and Newt Knight, he stopped, looked puzzled, and began to chuckle. “You’ve got the wrong Doug Jefcoate,” he said. “I’m not that guy.” (Turns out he is Doug Jefcoat, without the “e.”)

He laughed uproariously, then settled down and gave me his thoughts. “I’m not a racist, OK, but I am a segregationist,” he said. “And ol’ Newt was skinny-dipping in the wrong pool.”

The Rosin Heel commander Doug Jefcoate wasn’t available, so I went instead to the law offices of Carl Ford, a Rosin Heel who had unsuccessfully defended Sam Bowers, the imperial wizard of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, in his 1998 trial for the 1966 murder of civil rights activist Vernon Dahmer. Ford wasn’t there, but he’d arranged for John Cox, a friend, colleague and fellow Rosin Heel, to set me straight about Newt Knight.

Cox, an animated 71-year-old radio and television announcer with a long white beard, welcomed me into a small office crammed with video equipment and Confederate memorabilia. He was working on a film called Free State of Jones: The Republic That Never Was, intended to refute Gary Ross’ film. All he had so far was the credits (Executive Producer Carl Ford) and the introductory banjo music.

“Newt is what we call trailer trash,” he said in a booming baritone drawl. “I wouldn’t have him in my house. And like all poor, white, ignorant trash, he was in it for himself. Some people are far too enamored of the idea that he was Martin Luther King, and these are the same people who believe the War Between the States was about slavery, when nothing could be further from the truth.”

There seemed no point in arguing with him, and it was almost impossible to get a word in, so I sat there scribbling as he launched into a long monologue that defended slavery and the first incarnation of the Klan, burrowed deep into obscure Civil War battle minutiae, denied all charges of racism, and kept circling back to denounce Newt Knight and the simpering fools who tried to project their liberal agendas on him.

“There was no Free State of Jones,” he concluded. “It never existed.”

**********

Joseph Hosey is a Jones County forester and wild mushroom harvester who was hired as an extra for the movie and ended up playing a core member of the Knight Company. Looking at him, there’s no reason to ask why. Scruffy and rail-thin with piercing blue eyes and a full beard, he looks like he subsists on Confederate Army rations and the occasional squirrel.

He wanted to meet me at Jitters Coffeehouse & Bookstore in Laurel, so he could show me an old map on the wall. It depicts Jones County as Davis County, and Ellisville as Leesburg. “After 1865, Jones County was so notorious that the local Confederates were ashamed to be associated with it,” he says. “So they got the county renamed after Jefferson Davis, and Ellisville after Robert E. Lee. A few years later, there was a vote on it, and the names were changed back. Thank God, because that would have sucked.”

Like his grandfather before him, Hosey is a great admirer of Newt Knight. Long before the film, when people asked where he was from, he would say, “The Free State of Jones.” Now he has a dog named Newt, and describes it as a “Union-blue Doberman.”

Being in the film, acting and interacting with Matthew McConaughey, was a profound and moving experience, but not because of the actor’s fame. “It was like Newt himself was standing right there in front of me. It made me really wish my grandfather was still alive, because we were always saying someone should make a movie about Newt.” Hosey and the other actors in the Knight Company bonded closely during the shoot and still refer to themselves as the Knight Company. “We have get-togethers in Jones County, and I imagine we always will,” he says.

I ask him what he admires most about Knight. “When you grow up in the South, you hear all the time about your ‘heritage,’ like it’s the greatest thing there is,” he says. “When I hear that word, I think of grits and sweet tea, but mostly I think about slavery and racism, and it pains me. Newt Knight gives me something in my heritage, as a white Southerner, that I can feel proud about. We didn’t all go along with it.”

After Reconstruction, with the former Confederates back in charge, the Klan after him, and Jim Crow segregation laws being passed, Knight retreated from public life to his homestead on the Jasper County border, which he shared with Rachel until her death in 1889, and continued to share with her children and grandchildren. He lived the self-sufficient life of a yeoman Piney Woods farmer, doted on his swelling ranks of children and grandchildren, and withdrew completely from white society.

He gave that single long interview in 1921, revealing a laconic sense of humor and a strong sense of right and wrong, and he died the following year, in February 1922. He was 84 years old. Joseph Hosey took me to Newt’s granddaughter’s cabin, where some say that he suffered a fatal heart attack while dancing on the porch. Hosey really wanted to take me to Newt Knight’s grave. But the sacred rite of hunting season was underway, and the landowner didn’t want visitors disturbing the deer in the area. So Hosey drove up to the locked gate, and then swiped up the relevant photographs on his phone.

Newt’s grave has an emblem of Sal, his beloved shotgun, and the legend, “He Lived For Others.” He’d given instructions that he should be buried here with Rachel. “It was illegal for blacks and whites to be buried in the same cemetery,” says Hosey. “Newt didn’t give a damn. Even in death, he defied them.”

**********

There were several times in Jones County when my head began to swim.

During my final interview, across a brightly colored plastic table in the McDonald’s in Laurel, there were moments when my brain seized up altogether, and I would sit there stunned, unable to grasp what I was hearing. The two sisters sitting across the table were gently amused. They had seen this many times before. It was, in fact, the normal reaction when they tried to explain their family tree to outsiders.

Dorothy Knight Marsh and Florence Knight Blaylock are the great-granddaughters of Newt and Rachel. After many decades of living in the outside world, they are back in Soso, Mississippi, dealing with prejudice from all directions. The worst of it comes from within their extended family. “We have close relatives who won’t even look at us,” says Blaylock, the older sister, who was often taken for Mexican when she lived in California.

“Or they’ll be nice to us in private, and pretend they don’t know us in public,” added Marsh, who lived in Washington, D.C. for decades. For simplification, she said that there were three basic groups. The White Knights are descended from Newt and Serena, are often pro-Confederate, and proud of their pure white bloodlines. (In 1951, one of them, Ethel Knight, published a vitriolic indictment of Newt as a traitor to the Confederacy.) The Black Knights are descended from Newt’s cousin Dan, who had children with one of his slaves. The White Negroes (a.k.a. the Fair Knights or Knight Negroes) are descended from Newt and Rachel. “They all have separate family reunions,” said Blaylock.

The White Negro line was complicated further by Georgeanne, Rachel’s daughter by another white man. After Rachel died, Newt and Georgeanne had children. “He was a family man all right!” said Marsh. “I guess that’s why he had three of them. And he kept trying to marry out the color, so we would all keep getting lighter-skinned. We have to tell our young people, do not date in the Soso area. But we’re all fine. We don’t have any...problems. All Knights are hardworking and very capable.”

In the film, Marsh and Blaylock appear briefly in a courthouse scene. For the two of them, the Knight family saga has continued into the 20th century and beyond. Their cousin Davis Knight, who looked white and claimed to be white, was tried for the crime of miscegenation in 1948, after marrying a white woman. The trial was a study in Mississippian absurdity, paradox, contradiction and racial obsessiveness. A white man was convicted of being black; the conviction was overturned; he became legally white again.

“We’ve come to terms with who we are,” says Blaylock. “I’m proud to be descended from Newt and Rachel. I have so much respect for both of them.”

“Absolutely,” says Marsh. “And we can’t wait to see this movie.”