The True Story of ‘Mrs. America’

In the new miniseries, feminist history, dramatic storytelling and an all-star-cast bring the Equal Rights Amendment back into the spotlight

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/e2/8ee28465-7812-469f-9f9a-cc88da32720f/image.jpeg)

It is 1973, and conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly and feminist icon Betty Friedan trade verbal barbs in a contentious debate over the Equal Rights Amendment at Illinois State University. Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique and “the mother of the modern women’s movement,” argues that a constitutional amendment guaranteeing men and women equal treatment under the law would put a stop to discriminatory legislation that left divorced women without alimony or child support. On the other side, Schlafly, an Illinois mother of six who has marshalled an army of conservative housewives into an unlikely political force to fight the ERA, declares American women “the luckiest class of people on earth.”

Then Schlafly goes for the jugular. “You simply cannot legislate universal sympathy for the middle-aged woman,” she purrs, knowing that Friedan had been through a bitter divorce. “You, Mrs. Friedan, are the unhappiest women I have ever met.”

“You are a traitor to your sex, an Aunt Tom,” fumes Friedan, taking the bait. “And you are a witch. God, I’d like to burn you at the stake!”

Friedan’s now-infamous rejoinder is resurrected in this fiery exchange in “Mrs. America,” the nine-part limited series from FX on Hulu. Combining real history with the standard dramatic license, the scene captures the spirit and vitriol between pro- and anti-ERA factions during the fight for women’s equality. Starring Cate Blanchett as Schlafly, the Dahvi Waller-created show chronicles the movement to ratify the ERA, Schlafly’s rise to prominence and the contentious forces that epitomized the culture wars of the 1970s.

Creating a historical drama that portrays real events and people, some of whom are still living, calls for a delicate balance between historical accuracy and compelling storytelling. “All the events depicted in “Mrs. America” are accurate, all the debates we show actually happened,” says Waller, whose previous television credits include writing for the award-winning drama “Mad Men.” For research, Waller drew on archival materials, newspaper articles, read numerous books (about Schlafly and by and about leaders of the feminist movement) and watched TV footage and documentaries. She also drew on the Schlafly biography Sweetheart of the Silent Majority by Carol Felsenthal, who worked as a consultant on the series.

After Blanchett signed on to act in and executive produce the series, Waller hired six writers to work on the episodes and brought on researchers and fact-checkers to ensure historical accuracy.

“I was also interested in the conversations behind the scenes, the material you don’t read about, such as what happened in Phyllis’ home. For that, our job was to read source material and imagine what happened,” Waller says. “The emotional stories are where I took liberties.”

Many of the scenes in “Mrs. America” are based on real events: the 1972 Democratic Convention in Miami and Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm’s bid as the first black woman to run for president on the Democratic ticket, the Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion the following year and the 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston, which brought together many of the prominent leaders of the feminist movement. The show also covers how the push for the ERA faced an unexpected backlash from Schlafly and her supporters, who contended that the amendment would cause their daughters to be drafted, make same-sex bathrooms commonplace, and force them away from their babies and into the workplace.

Though the series centers on Schlafly, a who’s-who of ’70s feminist icons also figure prominently: Freidan (Tracy Ullman), Ms. magazine editor in chief Gloria Steinem (Rose Byrne), liberal firebrand Bella Abzug (Margo Martindale), Republican Jill Ruckelshaus (Elizabeth Banks) and Chisholm (Uzo Aduba). Actress Sarah Paulson plays a fictional character of a Schlafly loyalist whose political beliefs shift over the course of the series. Less well-known members of the women’s movement also appear in various episodes, including black lesbian feminist writer Margaret Sloan (who appears as a Ms. writer) and civil rights lawyer Florynce “Flo” Kennedy.

According to Waller, all of the series’ characterizations reflect her desire to convey each figure as a flesh-and-blood person. In Schlafly, Waller says she discovered a gifted, patriotic woman who feared communism and took on the anti-ERA fight after being thwarted in her chosen areas of interest—national security and defense. These skills were on full display in how she ultimately led her army of homemakers like a general off to war,

“Phyllis Schlafly was a fiercely intelligent, cunning, ambitious doer,” says Waller. “Her grassroots organizing skills were brilliant, and she had an ability to connect with the fears of women. In some ways she was the original brander.”

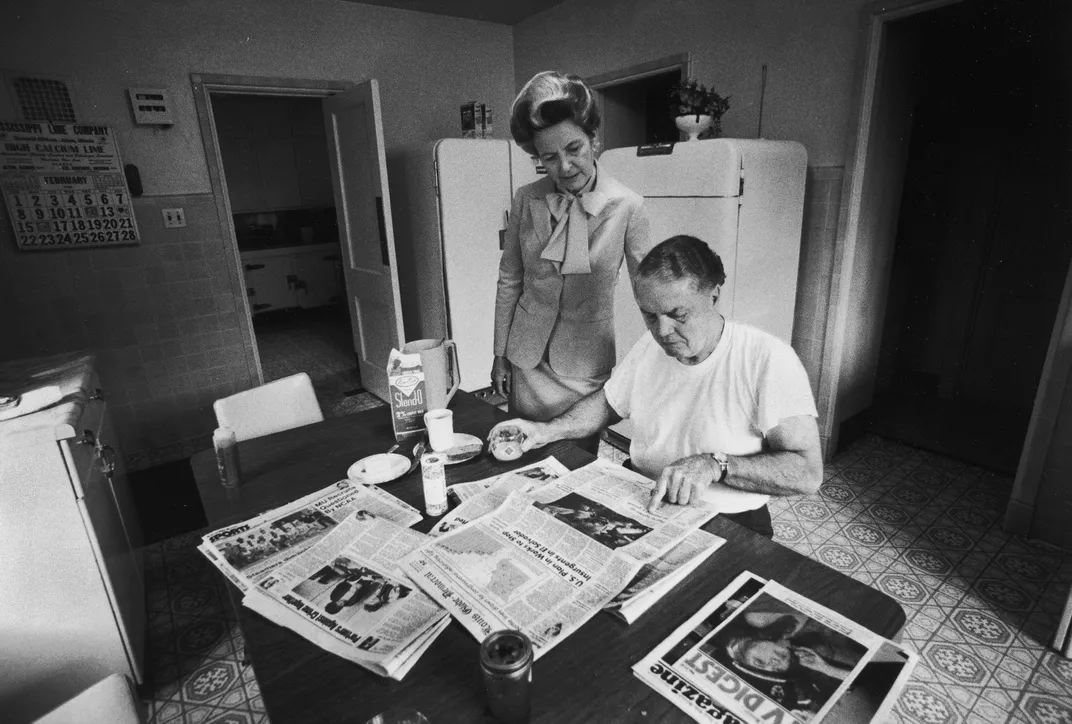

Schlafly had been politically active in Illinois Republican circles—and was late to the game—when she decided to take on the ERA and was confident, if not supremely composed, in defending what she deemed appropriate social mores. She could activate a phone tree and deploy hundreds of foot soldiers in minutes to a march or rally, and she pioneered the national campaign known as STOP (Stop Taking Our Privileges) ERA. The organization ran state-by-state campaigns to block the amendment’s ratification; her tactics included delivering baked bread to legislators to curry their votes. She wrote a number of books, including four on nuclear strategy; a self-published manifesto helped Barry Goldwater get the Republican presidential nomination in 1964, and ran for Congress in Illinois twice (and lost). Schlafly also went to law school at 50, against her husband’s wishes the series suggests. She was, as “Mrs. America” points out, a feminist in action if not in name.

Though she made her name defending a woman’s right to stay home, Schlafly seemingly preferred being out in the world and hobnobbing with powerbrokers (especially male ones). In one (fictional) scene, a thrilled Schlafly is finally invited to sit in on a meeting with Senator Jesse Helms, only to be crushed when asked to take notes as the only woman in the room.

Blanchett, who was raised in Australia, admittedly hadn’t heard of Schlafly before she accepted the role. She immersed herself in learning about her character to bring Schlafly to life on the screen— her impeccable posture, upswept hairdo and steely resolve, borne of childhood fears of being abandoned and not having enough money.

“Her father was unemployed, and therein lies the rub,” says Blanchett. “She grew up in a contradictory household. Her husband Fred [John Slattery] saved her from life of a working girl, but she gravitated always towards the notion of defense and had a foundational understanding that she needed to take care of herself and make a living should she be abandoned.”

Waller told the cast that she was more interested in identifying their characters’ essences than doing impersonations. “I tried to put myself inside their heads and figure out what drove them. I always looked for specificity of character,” she says.

She mined small details. For example, in her readings she had come across an item about how Steinem would forage the desks of Ms. employees for candy and Tootsie Rolls at night when she was working alone, then leave them notes if she took something, a behavior that made it into the series.

Actress Uzo Aduba (“Orange is the New Black”) watched footage of Chisholm to study her movements and speech patterns, the way she confrontationally looked into a camera and repeatedly adjusted her glasses.

“I wanted to learn how she defined herself versus how the world might define her,” says Aduba. “After reading her speeches, I started to realize that Chisholm was the first ‘hope candidate.’ Everything she stood for and spoke about was possibility.”

The tensions and divisions within the ranks of the women’s movement serve to heighten the drama of the miniseries. With impressive attention to nuance, “Mrs. America” touches on stylistic differences that created conflicts: Abzug wanted to work within the system while Chisholm pushed a revolutionary style, declaring, “Power concedes nothing.” Women of color and lesbians felt sidelined in the struggle to ratify the ERA. Moderate Republicans like feminist activist Jill Ruckelshaus, the wife of Nixon’s deputy attorney general, watched in dismay as their party moved to the right. Meanwhile, Friedan sometimes resented Steinem, the glamorous face of the feminist movement.

The miniseries’ nine episodes, each of which is named after a main character in “Mrs. America,” display these complicated dynamics. History buffs may identify some of creative liberties taken, but viewers receive an abundance of information about the forces that positioned Schlafly and conservatives against second-wave feminists and pro-ERA factions.

As “Mrs. America” relates, feminist leaders at first underestimated the threat Schlafly posed to the ERA. According to Jane Mansbridge, author of Why We Lost the ERA, after the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Roe, evangelicals and church leaders grew more willing to jump into politics and joined forces with Schlafly to defeat the amendment passed the year prior. While Schlafly was the public face of the anti-ERA movement, activists then and now believe its support also came from special corporate interests that benefitted financially from the existing inequalities.

* * *

The relevance of “Mrs. America”—that the culture wars over gender and the political power of the evangelical right remain alive and well in 2020—gives the series an emotional resonance. But politics was always a driving force behind the project, which originated in 2015 when Hillary Clinton seemed bound for the White House and Waller and co-executive producer Stacey Sher were searching for ideas to pitch to FX. With President Trump’s election, however, the women shifted their creative approach.

“I remember thinking, Oh, this whole show needs to change,” Waller told Vanity Fair “It’s not just about the Equal Rights Amendment—it’s much larger than that. In many ways, you can see the series as an origin story for the culture wars of today. You could see how all the fault lines develop. This was the rise of the religious right. That wasn’t in the elevator pitch—that all came out of living through the 2016 elections. Originally it was: won’t it be ironic to tell the story of one of the most famous anti-feminists when we have a woman president?”

Though the series’ sympathy leans leftward, its portrayals of the women on both sides of the ERA fight to avoid caricature. “It was important to me to write a series that was fair and compassionate to all the characters, even those I don’t agree with,” says Waller.

In the end—of “Mrs. America” and in real life—Schlafly helped defeat the ERA, which failed to meet its congressionally instituted deadline for ratification. But as Mansbridge points out, the ERA failed to pass by just a three-state margin, not a nation-wide mandate. Schlafly returned to writing books and publishing her newsletter (she died in 2016 at 92), but according to her biographer Carol Felsenthal, she never fulfilled her grander ambitions and was excluded from the corridors of real power, perhaps because she was a woman.

Though Schlafly managed to derail the ERA, she did not kill it. The epilogue to “Mrs. America” provides an update: This year, Virginia became the 38th state to pass the ERA, and the Democratic-led U.S. House of Representatives has passed a resolution to rescind the long-expired deadline for its ratification. Though a line also states that the Republican-controlled U.S. Senate is unlikely to take up the issue of ERA ratification, a robust coalition of women’s groups express confidence that the ERA will finally make its way into the U.S. Constitution in the near future. A “Mrs. America” sequel, perhaps?