The True Story of ‘The Trial of the Chicago 7’

Aaron Sorkin’s newest movie dramatizes the clash between protestors on the left and a federal government driven to making an example of them

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/20/4620f931-55ce-4f3a-8cbe-c8975d703cfc/trial-of-the-chicago-7-embed04a.jpg)

It was one of the most shocking scenes to ever take place in an American courtroom. On October 29, 1969, Bobby Seale, a co-founder of the Black Panther Party and one of eight co-defendants standing trial for inciting the riots that erupted at Chicago's 1968 Democratic National Convention, was gagged and chained to his chair for refusing to obey Judge Julius Hoffman’s contempt citations.

Seale hadn’t been involved in organizing the anti-Vietnam War demonstration, which began peacefully before turning into a bloody confrontation with police that resulted in nearly 700 arrests. He had spent only four hours in Chicago that weekend, having travelled there to fill in as a speaker. Outraged at being falsely accused, Seale vociferously interrupted the proceeding, asking to represent himself and denouncing the judge as a “racist pig.” Hoffman, an irascible 74-year-old with blatant disdain for the defendants, ordered Seale restrained. The image of a Black man in shackles, rendered by courtroom artists because cameras weren’t allowed in the courtroom, was circulated by media around the world.

“His whole face was basically covered with a pressure band-aid, but he could still be heard through it trying to talk to the jury,” recalls Rennie Davis, a co-defendant in what became known as the Chicago 8 trial (later Chicago 7 when Seale was legally severed from the group and was tried separately.)

This unforgettable scene is recreated in Netflix’ upcoming courtroom drama The Trial of the Chicago 7, which starts streaming on October 16—52 years after the real proceedings unfolded in downtown Chicago. Written and directed by Aaron Sorkin (The Social Network, A Few Good Men), the movie dramatizes the infamous, at times farcical, trial of eight men accused by President Nixon’s Justice Department of criminal conspiracy and crossing state lines to incite a riot. Dragging on for almost five months—at times devolving into chaos and political theater—the trial illuminated the deepening schisms in a country torn apart by the Vietnam War, tectonic cultural shifts and attempts by the Nixon Administration to quash peaceful antiwar dissent and protest. The drama and histrionics in the courtroom were reflected in daily headlines. Protesters outside the courthouse each day chanted the iconic mantra: “The whole world is watching!”

The road to the trial began the previous summer, when more than 10,000 antiwar demonstrators flocked to Chicago for five days during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The country was in turmoil, reeling from the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Senator Robert Kennedy and the worsening Vietnam War. President Lyndon Johnson, beleaguered and defeated by the war, had made the unprecedented decision not to seek a second term; after Kennedy’s death, Vice President Hubert Humphrey stood as the heir to the presidential nomination. But the Democratic Party was as divided as the rest of the nation: The antiwar contingent opposed Humphrey, while Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy appealed to students and activists on the left.

“Myself and others in [the antiwar group Students for a Democratic Society] (SDS)] went to Chicago to convince the kids in their teens and early 20s who had been campaigning for McCarthy to give up their illusions about getting change within the system,” says Michael Kazin, a history professor at Georgetown University who is currently writing a history of the Democratic party. “At the time, we were very cynical about the Democrats. We didn’t think there was any chance that McCarthy would be nominated. We wanted to give up the illusion of change through the existing electoral system.”

Organizers were planning a non-violent demonstration. But when thousands, many of them college students, arrived in Chicago, they were met by the forces of Democratic Mayor Richard Daley and his law-and-order machine—a tear-gas spraying, baton-wielding army of 12,000 Chicago police officers, 5,600 members of the Illinois National Guard and 5,000 U.S. Army soldiers. The protests turned to bloodshed.

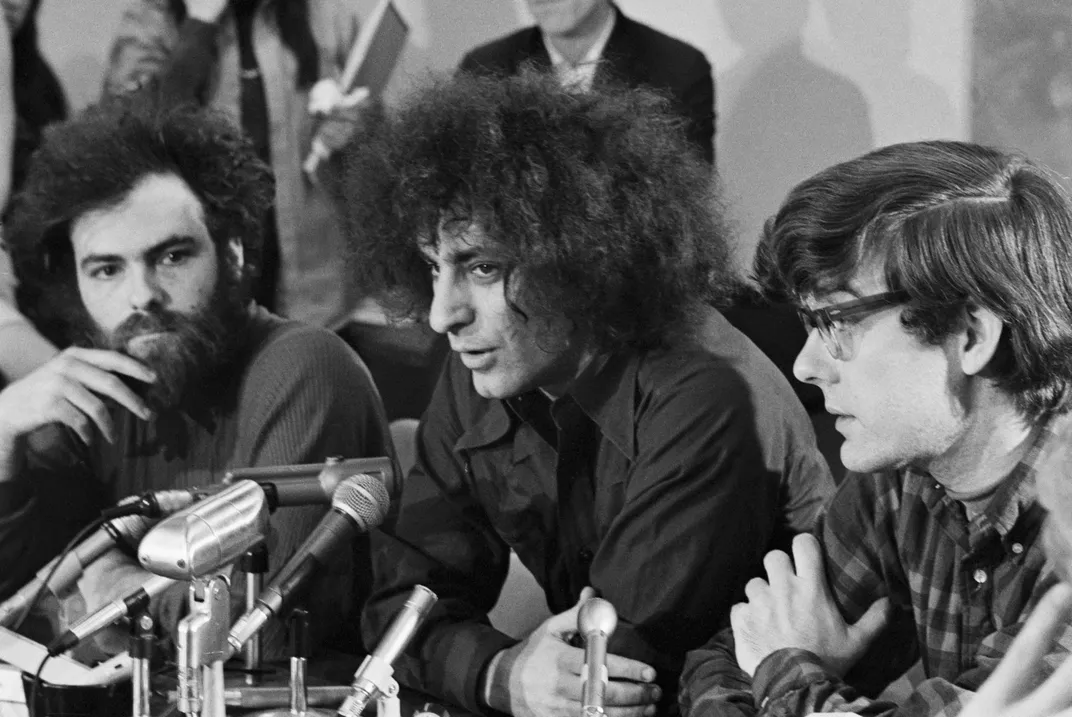

At the trial 12 months later, the eight defendants remained united in their opposition to the war in Vietnam, but they were far from a homogenous coalition. They represented different factions of “the movement” and had distinctly different styles, strategies and political agendas. Abbie Hoffman (played by Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong) were the counterculture activists of the Youth International Party (yippies), who brought a tie-dye, merry-prankster sensibility to their anti-authoritarianism. Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) and Davis (Alex Sharp), founders of SDS, lead a campus coalition of 150 organizations bent on changing the system and ending the war. David Dellinger (John Carroll Lynch)—literally a Boy Scout leader—was a pacifist and organizer for the Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE), which had been formed the previous year to plan large anti-war demonstrations. Professors John Froines and Lee Weiner (Danny Flaherty and Noah Robbins), who were only peripherally involved in planning the Chicago demonstrations (sitting at the defense table, one of them likens their presence to the Academy Awards. “It’s an honor just to be nominated.”) though they were thought to have been targeted as a warning to other academics who might engage in anti-war activities. Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) was head of the Chicago Panthers, which leaned towards more militant methods. The two lawyers representing the defendants, William Kunstler (Mark Rylance) and Leonard Weinglass (Ben Shenkman), were renowned civil rights attorneys.

Hollywood routinely tackles movies about real-life events, but dramatic storytelling and historical accuracy don’t always mix. In The Trial of the Chicago 7, Sorkin intentionally opts for broad strokes to revisit the story of the trial and the surrounding events. He makes no claims of hewing exactly to the true history, explaining that the movie is meant to be a “painting” rather than a “photograph”— an impressionistic exploration of what really happened.

For the sake of good storytelling, some timelines are rearranged, relationships are changed and fictional characters are added (a Sorkin-invented female undercover cop lures Jerry Rubin, for example).

“Before a film can be anything else—relevant or persuasive or important—it has to be good,” says Sorkin. “It has to tend to the rules of drama and filmmaking, so I’m thinking about the audience experience . . .This isn’t a biopic. You will get the essence of these real-life people and the kernel of who they are as human beings, not the historical facts.”

Sorkin takes some dramatic license is in his depiction of the emotional engine that drives the story: the relationship between Hayden and Hoffman. In the movie, the tension between the two men is palpable yet understandable given their stylistic differences. Hoffman—played by Cohen with a surprisingly respectable New England accent (Hoffman hailed from Worcester. Massachusetts)—is a pot-smoking hippie who wears his politics on the tip of his tongue. In shaping his portrayal, Cohen says he came to believe that despite his theatrics, Hoffman was a serious activist.

“What becomes clear is that in the end, Abbie is willing to challenge the injustice of the time,” says Cohen. “[Sorkin] shows that Abbie is willing to sacrifice his life. It was inspiring to play someone so courageous.”

Within the movement, however, the yippies were regarded as political lightweights, adept at public relations and little else, according to Todd Gitlin, a Columbia University journalism and sociology professor who served as president of SDS in 1963 and 64. “SDS saw them as clowns with a following that had to be accommodated, but they weren’t part of strategic planning for what should happen,” says Gitlin, who also wrote The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage.

In Sorkin’s script, Hayden and Hoffman start out antagonistic and eventually become comrades. Hayden is depicted as a clean-cut anti-war activist who stands up when the judge walks into the courtroom (he reflexively forgets that the defendants all agreed to stay seated) and gets a haircut for his first day in court. He wants to work within the system and shows his disdain for Rubin and Hoffman. In reality, Hayden was a revolutionary, co-founder with Davis of SDS and one of the primary architects of the New Left, He was also co-author of the seminal 1962 Port Huron statement, a political manifesto and leftist blueprint for creating a more participatory democracy.

“Had the government not brought them together at a conspiracy trial, I don’t think Hayden and Hoffman would have had much to do with each other,” says Gitlin.

In the courtroom, both the cinematic and the real-life versions, the defendants exhibited solidarity. From the day the trial began on September 24, 1969, it captivated the media. Kunstler’s defense strategy was one of disruption, and it worked. On the first day, Hayden gave a fist salute to the jury. Hoffman and Rubin pretty much spent the next four-and-a-half months at the defendants table turning the trial into political theater. Hoffman liked to provoke the judge (Frank Langella) by calling him “Julie” and blowing kisses to the jury. On one occasion which, of course, is included in the movie, the two yippies arrive in court wearing judicial robes, which they removed on the judge’s orders to reveal blue policeman’s uniforms underneath. Judge Hoffman (no relation to Abbie) was so angry that he continuously cited contempt. Even Kunstler received a four-year sentence, in part for calling Hoffman’s courtroom a “medieval torture chamber.”

“There was a lot of electricity in the air,” recalls Charles Henry, professor emeritus of African American studies at the University of California, Berkeley, who attended the trial while in college. “What I remember most vividly were Kunstler and Weinglass, who were doing the talking for the defense at the time, getting up a couple of times and before they could get a word out of their mouths [Judge] Hoffman overruled. I thought, ‘This is crazy. How could this happen? This has to be appealed.’”

The arrest of the eight defendants during the 1968 protests and the subsequent trial were part of the federal government’s efforts to punish leftists and organizers of the anti-war movement. According to Gitlin, once Nixon became President in 1969, his Justice Department formed a special unit to orchestrate a series of indictments and trials. “Nixon was throwing down a marker in order to intimidate the entire anti-war movement. They cooked up this indictment that made no sense,” he says. Under Attorney General John Mitchell (John Doman), the government aggressively pursued the defendants deploying prosecutors Richard Schultz (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and Thomas Foran (J.C. Mackenzie). To its credit, the movie includes, if only suggests, some of these undercurrents.

Sorkin’s introduction to the Chicago 7 began more than a decade ago when director Steven Spielberg contacted him to talk about a movie on the trial. The idea was tabled when both men had other projects in the works, but Sorkin wrote a draft in 2007. He pored over the original transcripts, read numerous books on the trial and the politics of the ’60s and spent time with Hayden (who died in 2016) as part of his writing process. With the tumult of the 2016 election, Sorkin was re-inspired to examine the story of defiant activists willing to stand up for their political beliefs. This time around he would also direct.

As it turns out, the events from this past summer share many parallels to 1968. “We’re seeing the demonization of protest right now, especially in the midst of this political campaign,” says Sorkin.

That said, the trial of the Chicago 7 reflected the era: the cultural and political clashes of the late ‘60s and a Nixonian view of the world as the first federal trial aimed at intimidating anti-war activists. The judge was not only politically hostile towards the defendants but, historians say, tone-deaf to what was happening in the country and seemingly unaware of the symbolism of chaining Seale to a chair in his courtroom.

On February 18, 1970, the seven defendants were acquitted of conspiracy charges but fined $5,000 each. Five of them —Davis, Dellinger, Hayden, Hoffman and Rubin—were convicted of crossing state lines with the intent to riot. Froines and Weiner were acquitted of all charges. The seven defendants and their attorneys also received prison sentences for the more than 170 contempt citations levelled at them by Judge Hoffman—which ranged from two-and-a-half months (for Weiner) to four years and 18 days (for Kuntsler).

But the wheels of justice turned, and in 1972, all charges against the defendants were dropped. Among other reasons, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit cited Judge Hoffman’s “antagonistic” courtroom demeanor. Charges against Seale were also dropped. A subsequent investigation and report concluded that the 1968 demonstration’s bloody turn was instigated by the police.

Fifty-two years later, the movie, like the trial itself, points to the power citizens can exert through protest in the face of authoritarian rule. “We were facing ten years in jail. We would get 30 death threats a day while on trial,” recalls Davis, who jokes that he wasn’t as nerdy as he is portrayed in the movie. “It was very intense, yet no one ever forgot that we were there for one reason only: our opposition to the war in Vietnam. We put the government on trial.”

The Chicago 8: Where Are They Now?

Rennie Davis: Now 80, Davis founded the Foundation for a New Humanity, a Colorado-based project to develop a comprehensive plan for a new way of living. Married, he lives in Boerthoud, Colorado and also does personal growth coaching.

David Dellinger: Dellinger died in 2004 at 88. The oldest of the Chicago defendants by 20 years, he was a leading antiwar organizer in the 1960s. Dellinger wrote From Yale to Jail: The Life Story of a Moral Dissenter.

John Froines: At 81, Froines is professor emeritus at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health with a specialty in chemistry, including exposure assessment, industrial hygiene and toxicology. He also served as director of a division of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration .

Tom Hayden: Hayden died in 2016 at 76. A leader in America’s civil rights and antiwar movements, he moved into mainstream politics and served in the California State Assembly for a decade and the California State Senate for eight years. He taught at Occidental College and Harvard's Institute of Politics. The author of 17 books, he was also director of the Peace and Justice Resource Center in Los Angeles County. Hayden married three times, but his most high-profile union was to actress and fellow activist Jane Fonda for 17 years.

Abbie Hoffman: After spending years underground, Hoffman resurfaced in 1980, lectured at colleges and worked as a comedian and community organizer. He died in 1989 at 52 from a self-inflicted overdose of barbiturates due to bipolar disorder.

Jerry Rubin: Rubin went on to work on Wall Street and hosted networking events for young professionals in Manhattan. He died in 1994 at 56 after he was hit by a car near his Brentwood, California, home.

Bobby Seale: At 83, Seale resides in Liberty, Texas. In 1973, Seale ran for mayor of Oakland, California, and came in second out of nine candidates. He soon grew tired of politics and turned to writing, producing A Lonely Rage in 1978 and a cookbook titled Barbeque'n with Bobby in 1987.

Lee Weiner: Now 81, Weiner recently wrote Conspiracy to Riot: The Life and Times of One of the Chicago 7, a memoir about the1968 Democratic National Convention. In the years after the trial, Weiner worked for the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith in New York and participated in protests for Russian Jews and more funding for AIDS research He also worked as a vice president for direct response at the AmeriCares Foundation. He resides in Connecticut.