Twelve Fascinating Finds Revealed in 2019

The list includes a sorceress’ kit, a forgotten settlement, a Renaissance masterpiece and a 1,700-year-old egg

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/4b/604be510-28da-417b-aeea-5aecf2df8157/sorceress_charms.jpg)

Few topics manage to unite the masses quite like the macabre, the unexpected and the indisputably astonishing. Luckily, 2019 offered up all of these qualities in plenty: Significant discoveries of the year spanned disciplines, time, geographic locations and cultures. Some were first unearthed years ago but only documented now; others were identified more recently. From a long-lost Renaissance masterpiece to grisly accessories crafted out of human bone, a perfectly preserved wolf head and talismans designed to ward off evil, these were the most fascinating finds of 2019, ranked in order of popularity among our readers.

1. Hidden Japanese Settlement Found in Forests of British Columbia

During the first half of the 20th century, a group of Japanese Canadians settled down in a secluded enclave of British Columbia’s North Shore mountains, creating a small but thriving community that boasted rows of houses, gardens, a water reservoir, a shrine and a bathhouse. Here, says archaeologist Robert Muckle, immigrants and their Canadian-born children sought refuge from the rampant racism of pre-World War II Vancouver; among other limitations, Japanese individuals were barred from voting, entering the civil service and practicing law.

The North Shore settlement’s first residents were probably loggers employed on a nearby patch of land. Although the area’s forestry had been largely harvested by 1924, Muckle suspects the persecuted Japanese opted to remain in their tightknit community, “living here on the margins of an urban area, ... kind of in secret.”

World War II brought the villagers’ idyllic existence to an abrupt halt. Although Muckle hasn’t found direct evidence of habitation post-1920, he told Smithsonian magazine that the sheer amount of artifacts left at the site—the list of more than 1,000 recovered items includes rice bowls, buttons, ceramics, teapots, pocket watches and sake bottles—suggests the settlement was abandoned in a hurry, likely around 1942, when its residents “were incarcerated or sent to road camps.”

2. Archaeologists Unearth Remains of Infants Wearing 'Helmets' Made From the Skulls of Other Children

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/2c/ee2c3264-a3fd-42d2-96c2-67c704ff3af0/skull_2_copy.jpg)

Around 100 B.C., members of Ecuador’s Guangala culture interred a pair of infants at Salango, a ritual complex located on the country’s central coast. One was around 18 months old at time of death, while the other was between 6 to 9 months old. Both were buried in decidedly unusual headgear: namely, “helmets” made from the skulls of older children.

“The modified cranium of a second juvenile was placed in a helmet-like fashion around the head of the first, such that the primary individual’s face looked through and out of the cranial vault of the second,” wrote the researchers in a November Latin American Antiquity article.

The archaeologists suspect the older individuals’ skulls were still covered in flesh when placed over the infants’ heads. (Per the paper, juvenile skulls “often do not hold together” unless supported by skin.) The younger infant’s gruesome accessory was fashioned from the skull of someone aged 2 to 12 years old. The 18-month-old’s helmet, on the other hand, came from a 4- to 12-year-old child; the team also found a small shell and a finger bone in between the baby’s head and the second skull.

Although the researchers remain unsure of the bone helmets’ exact purpose, they propose several potential explanations: One theory suggests the extra skulls provided protection for the infants’ “presocial and wild” souls as they entered the afterlife, while another posits that the helmets belonged to the babies’ ancestors and were worn both in life and death.

The most plausible hypothesis, according to lead author Sara Juengst of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, links a “natural or social disaster” with the helmets’ probable purpose of offering “extra protection or extra links to ancestors.”

3. A Sorceress' Kit Was Discovered in the Ashes of Pompeii

In recent years, renewed archaeological excavations at Pompeii have yielded a veritable treasure trove of artifacts: among others, the ancient equivalent of a fast food counter, a bloody gladiator fresco, the still-saddled remains of a horse and an inscription dating Mount Vesuvius’ 79 A.D. eruption to October rather than August. (As Franz Lidz wrote for Smithsonian magazine in September, the finds stem from a $140 million conservation and restoration initiative, dubbed the Great Pompeii Project, launched in 2012 with financial support from the European Union.)

Of these finds, a sorceress’ kit filled with around 100 miscellaneous trinkets is perhaps the most intriguing. Containing carved scarab beetles, tiny dolls and skulls, crystals, phallic amulets, mirrors, and gems, the makeshift tool kit may have been used to tell fortunes, attract good luck, or conduct rituals associated with fertility and seduction.

Massimo Osanna, then-director general of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, told Italian news agency ANSA that the cache probably belonged to a slave or servant, as it lacks the gold accessories typically touted by Pompeii’s elites.

4. ‘Witch Bottle’ Filled With Teeth, Pins and Mysterious Liquid Discovered in English Chimney

“Witch bottles” filled with bent pins, nails, thorns, urine, fingernail clippings, hair and even teeth were regularly employed to ward off witchcraft between the 16th and 18th centuries. Per JSTOR Daily’s Allison C. Meier, this assortment of objects was believed to lure witches into the bottle, where they would become trapped on the pins’ sharp points. But by the mid-19th century, such talismans were considered outdated, making a witch bottle recently found at a former inn and pub in Watford, England—and dated to no earlier than the 1830s—an anomaly.

The torpedo-shaped vessel in question contained fish hooks, human teeth, shards of glass and an unidentified liquid (possibly urine). Contractors discovered the bottle while demolishing the chimney of the Watford property, formerly known as the Star and Garter. Practitioners often placed such bottles underneath hearths or near chimneys, as these openings were thought to grant witches passage into the home.

The protective charm was far from the Star and Garter’s first brush with witchcraft: Angeline Tubbs, a woman later dubbed the Witch of Saratoga, was born at the inn in 1761.

“It’s certainly later than most witch bottles, so sadly not contemporary with Angeline Tubbs,” Ceri Houlbrook, a historian and folklorist at the University of Hertfordshire, told BBC News, “but still a fascinating find.”

5. Lost Footage of One of the Beatles' Last Live Performances Found in Attic

On June 16, 1966, the Beatles performed “Paperback Writer” on an episode of the BBC television program “Top of the Pops.” The British broadcasting network failed to record or otherwise document the show, leading fans to believe it had been lost forever, but luckily, a music lover watching from home, David Chandler, decided to capture the Fab Four’s appearance with his personal wind-up camera. He then stored the footage in his attic for more than 50 years.

Chandler held on to the recording until this spring, when the discovery of a similar, albeit significantly shorter, clip of the “Top of the Pops” performance made headlines around the world. “I think if you're a Beatles fans, it’s the holy grail,” Chris Perry of Kaleidoscope, an organization that specializes in tracking down and restoring lost footage, told BBC News at the time. Inspired by the media blitz, Chandler sent Kaleidoscope his own 92-second clip.

The longer recording—deemed “phenomenal” by Perry—is silent, as is the 11-second one found by a collector earlier this year. But Kaleidoscope remastered the footage, syncing it with audio of “Paperback Writer” and enhancing the video’s quality, finally giving Beatles fans the chance to see the long-lost performance.

6. Archaeologists Unearth Hollowed-Out Whale Vertebra Containing Human Jawbone, Remains of Newborn Lambs

When a group of Iron Age Scots abandoned a broch, or roundhouse, on the Orkney Islands during the mid-second century A.D., they left behind an unusual vessel held in place by a pair of red deer antlers and a large grinding stone. The makeshift container, crafted from a hollowed-out whale vertebra, held a human jawbone and the remains of two newborn lambs.

“All this treatment appears to have been part of the measures employed to perform an act of closure of the broch,” reads a statement from the University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute.

DNA analysis conducted by UHI archaeologist Martin Carruthers and his colleagues identified the vertebra as a fin whale bone. Since fin whales are the world’s second largest whale species, the discovery led the researchers to question whether the ancient humans actively hunted the massive whale or simply made the most of a carcass swept ashore.

Additional sets of marine animal bones—among others, the species represented include sperm, humpback and minke whales, as well as dolphins and porpoises—unearthed at the archaeological site support the latter theory: As Carruthers told BBC News’ Huw Williams, “[That assemblage is] what you'd expect, I suppose, if you saw them as being quite opportunistic in terms of what came across their path.”

7. A Perfectly Preserved 32,000-Year-Old Wolf Head Was Found in Siberian Permafrost

The permafrost of Russia’s Siberian heartland wields virtually unmatched preservation power: In 2017, for instance, a local found the frozen remains of an extinct, potentially 50,000-year-old cave lion cub on the banks of the Tirekhtykh River, and in 2018, a group of mammoth tusk hunters unearthed the nearly intact remains of a 42,000-year-old foal. But perhaps the most exciting find of recent times was the fully intact head of an adult Pleistocene steppe wolf, preserved in permafrost for some 32,000 years.

The 2- to 4-year-old wolf belonged to an extinct lineage distinct from modern species. Although initial media reports described the severed head—still covered in fur—as unusually large, Love Dalén, an evolutionary geneticist at the Swedish Museum of Natural History who was involved in the discovery, told Smithsonian the wolf was “not that much bigger than a modern wolf if you discount the frozen clump of permafrost stuck to where the neck would [normally] have been.”

Researchers weren’t able to determine how and when the wolf’s head was separated from the rest of its body, but leading theories suggest the cranium was either deliberately cut off by humans, perhaps “contemporaneously with the wolf dying,” according to evolutionary biologist Tori Herridge, or lost during decomposition and permafrost shifts.

8. Cave Full of Untouched Maya Artifacts Found at Chichén Itzá

Fifty years after locals first reported the discovery of a cave system at Chichén Itzá—the famed Maya ruins located on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula—archaeologists finally ventured into the cavern’s depths. (Per the Associated Press, locals had informed an archaeologist of their initial find, but he ordered the cave sealed, possibly to protect the artifacts housed within, and issued a soon-forgotten report.) To access the multi-chambered network, researchers had to crawl on their stomachs through cramped passageways. Still, the importance of treasures revealed at the end of this arduous experience was well worth the trip: Inside, the team found 155 ceramic incense burners, clay boxes, vases, plates, and offerings left by ancient individuals hoping to attract rain by winning the favor of Tlaloc, rain god of central Mexico.

“I couldn’t speak, I started to cry,” archaeologist Guillermo de Anda told National Geographic’s Gena Steffens. “I’ve analyzed human remains in [Chichén Itzá’s] Sacred Cenote, but nothing compares to the sensation I had entering, alone, for the first time in that cave. You almost feel the presence of the Maya who deposited these things in there.”

9. The $26.8 Million Renaissance Masterpiece Found Hanging Above a Woman’s Hot Plate

In October, a small panel painting that nearly landed in the trash sold at auction for $26.8 million after experts authenticated it as a long-overlooked work by early Renaissance artist Cimabue. (The French government has since placed a 30-month export ban on the work, buying time to raise funds to purchase the artwork for the nation.) Titled Christ Mocked, the 13th-century masterpiece spent years hanging above an elderly French woman’s hot plate; per the Guardian’s Angelique Chrisafis, the work’s unwitting owner had always assumed it was a nondescript religious icon. She does not know how the painting ended up in her family’s possession.

Auctioneer Philomène Wolf happened upon the religious scene while clearing out the woman’s home.

“I had to make room in my schedule,” Wolf told Elie Julien of Le Parisien. “… If I didn’t, then everything was due to go to the dump.”

Researchers called in to assess the painting identified it as a probable panel from a polyptych created by Cimabue—perhaps best known as Giotto’s teacher but a pioneering artist in his own right—around 1280. Two other sections of the polyptych are known to survive today: One is housed at the Frick Collection in New York, while the other is owned by London’s National Gallery.

A line of tracks left by wood-gnawing larvae offered the most convincing evidence of the painting’s provenance.

“You can follow the tunnels made by the worms” across all three individual works, art historian Eric Turquin explained to the Art Newspaper’s Scott Reyburn. “It’s the same poplar panel.”

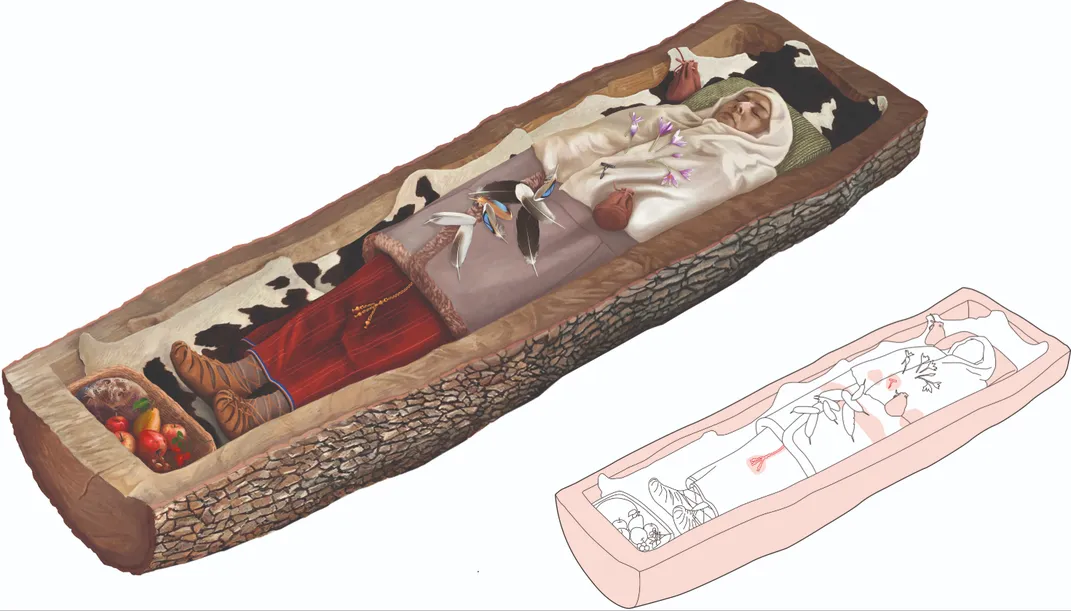

10. This Iron Age Celtic Woman Was Buried in a Hollowed-Out Tree Trunk

Around 2,200 years ago, an Iron Age Celtic woman was laid to rest in an unusual coffin fashioned out of a hollowed-out tree trunk. Richly attired in a dress of sheep’s wool, a sheepskin coat and a shawl, the roughly 40-year-old woman was likely an elite Celt: Based on researchers’ analysis of her remains, she rarely performed physical labor, instead indulging in a diet of starchy and sweetened foods.

Per a statement from Zürich’s Office for Urban Development (contrary to popular perception, Celtic clans lived across Europe, not just in the British Isles), archaeologists found the grave while renovating a school complex in the Swiss city. The woman, who was buried with accessories including an amber and glass necklace, bronze bracelets, and a bronze belt chain decorated with pendants, may have had ties to a male warrior whose remains were unearthed in the same area back in 1903. Both were buried around 200 B.C., making it “quite possible” they knew each other, according to the statement.

11. Archaeologists Discover Medieval Woman and Child's Skeletons at the Tower of London

The Tower of London has welcomed its fair share of formidable figures over the past millennia, playing host—or jailer—to such individuals as William the Conqueror, the Princes in the Tower, Guy Fawkes, Sir Walter Raleigh, Elizabeth I and Anne Boleyn. But the recent discovery of a pair of 500-year-old skeletons interred in one of the stronghold’s chapels offered a reminder of the Tower’s lesser known residents, many of whom played a vital role in the castle’s everyday operations.

Archaeologists unearthed the remains, dated to between 1450 and 1550, while conducting excavations at the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula earlier this year. One skeleton was identified as a woman who died between the ages of 35 and 45, while the other was judged to belong to a roughly 7-year-old child. Neither showed signs of a violent death, making it unlikely they were executed prisoners. Instead, Dalya Alberge reported for the Telegraph in October, the duo may have had ties to the Royal Mint, the Royal Armories or the soldiers assigned to guard the crown jewels.

The remains “have offered us a chance to glimpse that human element of the Tower which is so easy to miss,” wrote Alfred Hawkins, assistant historic buildings curator, in a blog post for Historic Royal Palaces. “This Fortress has been occupied for nearly 1000 years, but we must remember it is not only a Palace, Fortress and Prison but has also been a home to those who worked within its walls.”

12. Archaeologists Crack the Case of 1,700-Year-Old Roman Eggs

A pair of 1,700-year-old chicken eggs recovered from a waterlogged pit in central England emitted a pungent, sulfurous aroma when cracked during excavation. But a third egg retrieved from the same gaping hole remains intact, its rotten egg smell safely masked by a fragile shell.

The preserved egg—hailed by researchers as the only complete Roman egg ever found in Britain—was unearthed in a ditch at Berryfields, an ancient settlement located along a bustling Roman road. Archaeologists think the pit was used to brew beer during the second and third centuries, then transformed into a makeshift wishing well toward the end of the third century. The eggs, which were found alongside a bread basket, leather shoes, and assorted wooden vessels and tools, may have been a food offering tossed into the well in hopes of winning the gods’ favor.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)