The Nerdiest Christmas Cards Ever May Be These Microscope Slides Composed of Shells

The unusual holiday exchange, which lasted decades during the early 20th-century, hints at the drama between the two colleagues

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/a6/1fa615f1-fcf2-4692-9db4-77d626f84cd5/fossil-cover.jpg)

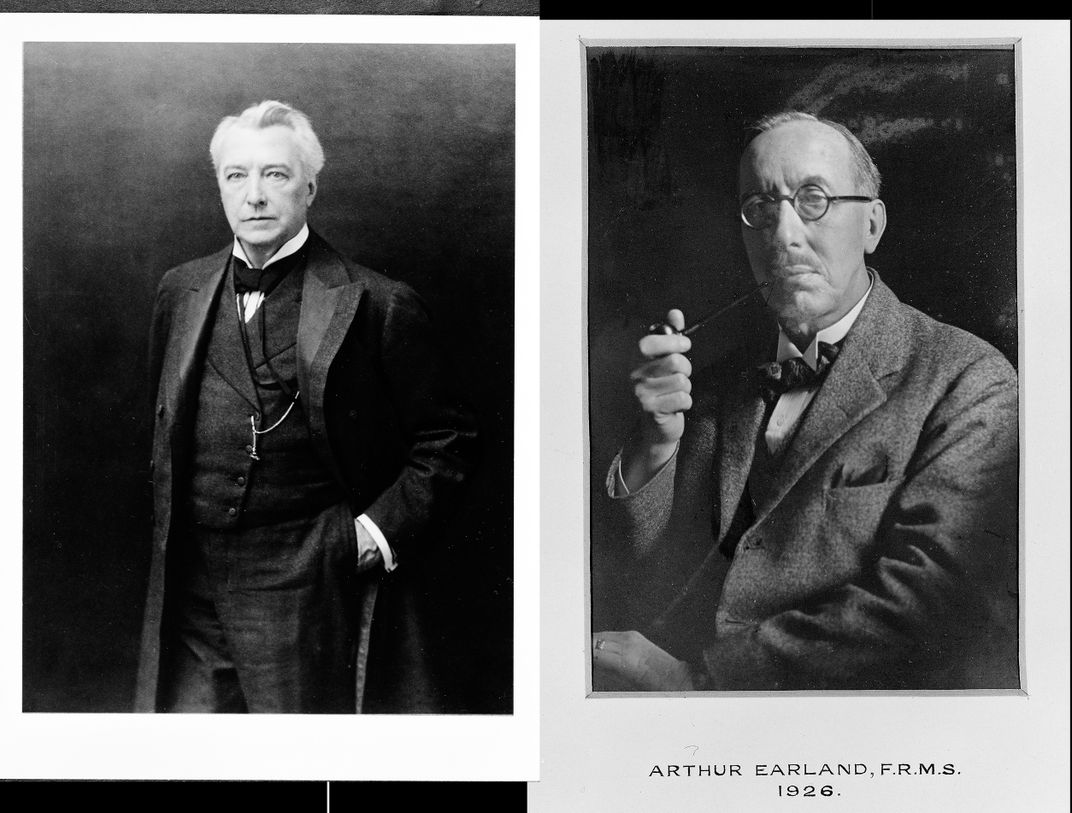

For more than 25 years, Arthur Earland and Edward Heron-Allen partnered in studying fossils of Foraminifera, a phylum of marine single-celled organisms often protected by shells of calcium carbonate. These abundant protists date back 540 million years, with around 4,000 species still in our oceans. Earland was a civil servant who spent his career with the Post Office Savings Bank; Heron-Allen was a lawyer and prolific polymath whose passions ranged from palmistry and violin-making to Persian literature and asparagus cultivation, with his colorful résumé even including brief possession of a supposedly cursed amethyst.

Neither trained as a scientist before taking on their unpaid positions at what today is known as the Natural History Museum, London (NHM). Established in 1881, the museum benefited from the work of such volunteers in its early years, whether from entomologist Evelyn Cheesman who worked there in the 1920s in an unpaid position in the natural history department, or from 19th-century botanist Ronald Campbell Gunn who contributed to its collections.

Foraminifera are not rare—some areas of the world are so abundant with them that their ocean bottom sediment is composed of their shells. For instance, the pink sands of Bermuda get their rosy hue from Homotrema rubrum, a species of red foraminifera that thrives on the nearby coral ledges. Nevertheless, in their global spread and millennia of life, they represent valuable records of evolution, archaeological dating and environmental change. Heron-Allen and Earland, for their part, arranged and catalogued specimens, including many new species, on hundreds of slides, to describe the variety of Foraminifera. As scientist R. L. Hodgkinson in the museum's department of paleontology wrote in 1989, the “Heron-Allen & Earland Type Slide Collection provides a magnificent example of a late Victorian-early 20th-century foraminiferal collection; the slides themselves and the labelling are works of art, the faunas are beautifully and painstakingly arranged and catalogued.”

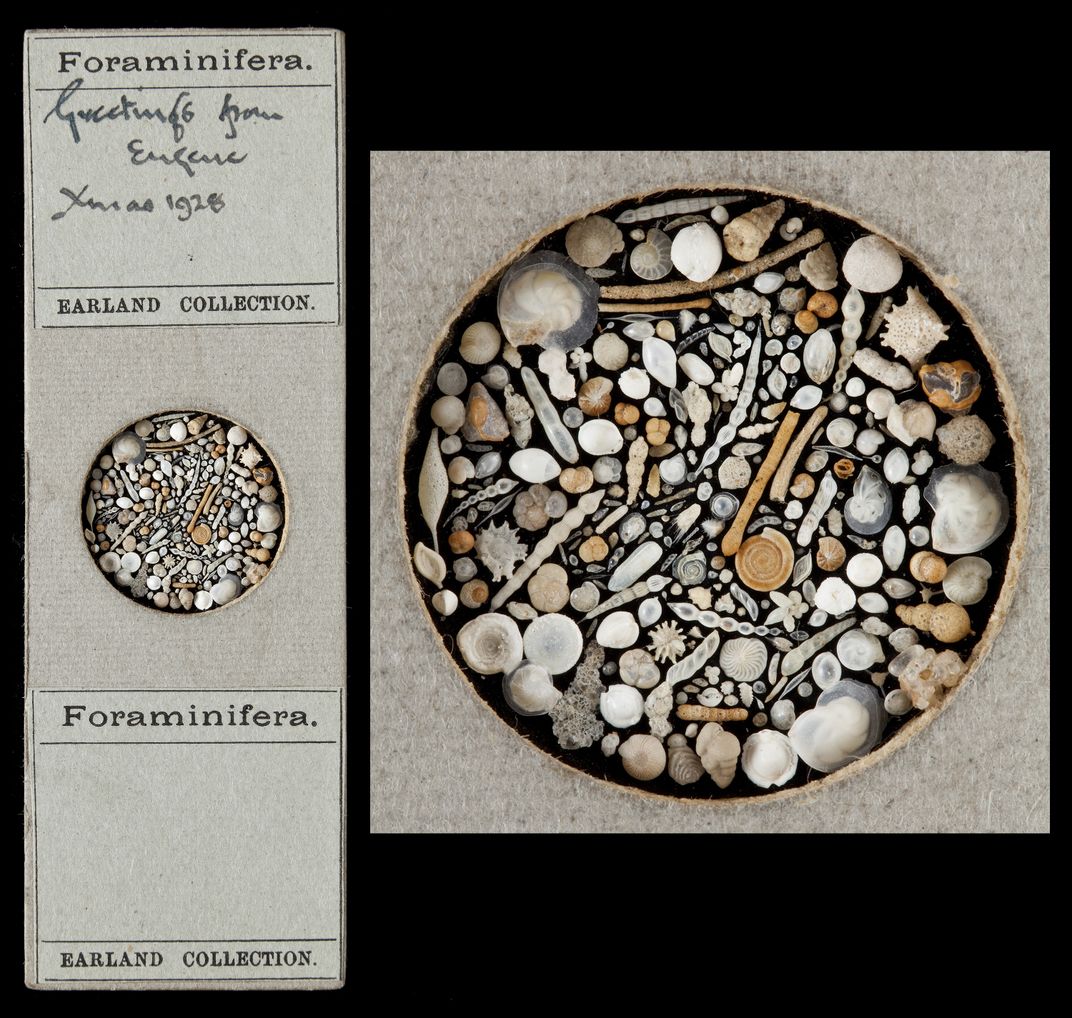

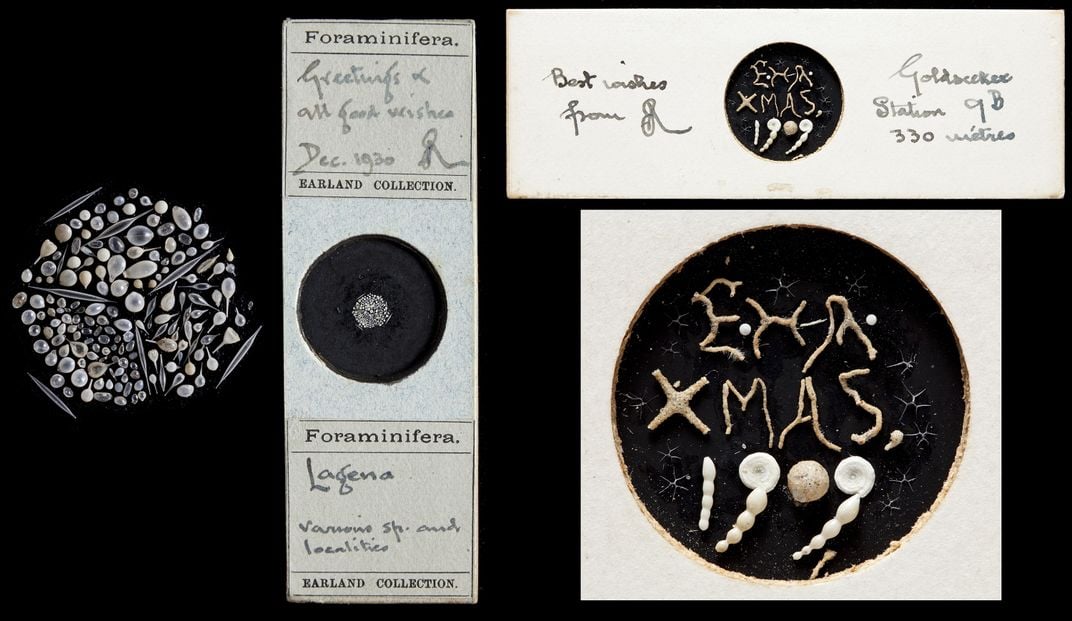

While mostly they concentrated on exploring the diverse forms of these fossils, as each December approached, they devoted time to more whimsical slide arrangements. These Christmas-themed slides, which the two exchanged over their years of collaboration, had personalized greetings spelled out with microfossils (a term for fossils measuring under 1mm in size) that would be visible under a microscope. One from 1912 has Earland’s initials (“AE”), “XMAS,” and the year in an arrangement that measures about 1cm across.

Several examples of their Christmas slides are now in the collections of NHM. The 1912 slide is a part of the museum’s touring exhibition Treasures of the Natural World alongside birds studied by Charles Darwin and an Iguanodon bone described by Richard Owen. More humble than these illustrious objects, the slide is still an incredible work of art and science, with each small fossilized shell carefully selected and delicately attached to the slide using a fine paint brush and Tragacanth gum.

In a 2011 NHM blog post, Giles Miller, principal curator of micropalaeontology (the study of microscopic remains), noted that Heron-Allen established a foundational part of the museum’s microfossil collection, including his bequest of his slides and a large library of foraminiferal books. His work with Earland involved analyzing and publishing the Foraminifera collected from ocean dredging on the 1910-1913 Terra Nova Antarctic expedition (on which Robert Falcon Scott and his whole accompanying party infamously died on their return from the geographic South Pole). In their publication on the Terra Nova Foraminifera, 650 species were described, including 46 then new to science. Significantly, some of these forms had already been witnessed in Arctic specimens, suggesting they evolved concurrently. They also described species from waters around the British Isles, east Africa and the Southern Ocean, their slides and studies further revealing the diversity and evolution of ocean life across the centuries.

Since the holiday slides were presumably made with surplus fossils, it’s possible they reflected the pair’s current research. For instance, in an August 5, 1915, article in Nature, Heron-Allen, in discussing their recent insights into the shells of these ancient organisms, wrote that the “protective investment” of the species Hyperammina ramosa “ramifies in a most remarkable manner, so much so that Earland once constructed for me a Christmas greeting slide” out of its variant forms. On the 1912 slide, the fossils used for lettering were sourced from the genus Rhabdammina, their tubular shapes created from sea floor sediment as a Foraminifera shelter.

Recently, NHM acquired Earland’s slide collection, including three Christmas messages from 1931, 1932 and 1936, yet these date from after a major falling-out between the two enthusiasts. A 2012 article in the Independent reported that in the early 1930s, their partnership dissolved, possibly due to conflicts over credit—or a more scandalous personal disagreement. (The Independent cites a 1943 letter in which Earland broods on “that final woman” who caused their rift.)

Miller, in a 2012 blog post, shared that in a 1933 scientific publication, Earland wrote that because of illness “Heron-Allen was unable to take as large a share as usual in the preparation of this report. At his own request, and against my wish, his name is omitted from the authorship.” However, a copy of the book owned by Heron-Allen has a handwritten declaration that his name was “removed from the titles of this paper, on my return from Ceylon in 1931 I found that Earland had claimed all my work upon it as his own.”

Even before this publication, there may have been simmering hostilities, as Earland did much of the slide work and Heron-Allen the writing, and with his greater wealth and professional connections, Heron-Allen was able to publish more. (Earland was never the first author listed on their joint papers.) This tension may have intensified when Heron-Allen alone was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society for his Foraminfera work in 1919.

Another factor may have been the death of Heron-Allen’s daughter Armorel in a 1930 car accident, just after she completed her studies in natural sciences. Whatever the cause, by anecdotal accounts the two men started going to the museum on different days as to not see each other. Miller said that since the newly acquired Earland slides “date from the time post Heron-Allen’s daughter’s death in 1930, we can only assume that Earland prepared them but never gave them to Heron-Allen as they had limited contact.” He added that there “are other slides in the Earland Collection that had preprinted slide labels that say ‘Heron-Allen and Earland Collection’ and the name Heron-Allen has been scored out. However, we’ll never know if this was done in spite or simply to delimit slides that Earland considered to be part of his separate collection. What is also clear is that Earland’s collection does not contain any Christmas card slides made by Heron-Allen and given to him.”

The fracturing of their friendship is visible in the final Christmas slides. Whereas earlier holiday slides were dense with detail, such as one from 1928 featuring an incredible wreath in which every minuscule shell seems to be a different shape, the final examples are more barren. One from 1930 made by Earland has notably fewer specimens, each hovering rather forlornly in the dark circle of the slide.

“I love the human aspect of these slides, particularly the stories behind them,” Miller said. “I also love that they show the beauty and variability of form of the Foraminifera.”

Heron-Allen died in 1943, and his voluminous obituary printed by the Royal Society pronounced him “a man of wide-ranging versatility, but whatever enterprise he took up he was never satisfied until with persistent energy he had probed to the fundamentals of it and placed the whole matter in historical sequence.” The author notes his work with Earland, his “exhaustive enquiry” into historical beliefs around barnacles, his recognition as “an authority on the occult,” the 16 years he spent on “cross-breeding experiments with asparagus in his spacious garden,” his study of “the Persian astronomer-poet, Omar Khayyim,” and his 1884 book Violin Making as it Was and Is. There’s now a Heron-Allen Society dedicated to studying the seemingly boundless interests of his life.

Earland, meanwhile, died in 1958. His much more-concise memorial in the Journal of Microscopy begins: "In the absence of men of science who knew him well, the writer, who met him only three or four times, has based this notice partly upon auto-biographical material culled from a 27-year correspondence with him.” One self-effacing quote from Earland relates that "in another 100 years it will puzzle [anyone] to learn anything about Earland, and he will never guess that he was just a poor ... Civil Servant who worked at Forams as a relief from the monotony of his job.”

Indeed, over a century later, there’s much more biographical information about Heron-Allen than Earland, and what exactly broke their bond remains a mystery. Yet in this unique holiday exchange, with its exquisitely arranged greetings, is evidence of the passion that fueled their friendship, and some of the most important early research on these tiny fossils.