Uganda: The Horror

In Uganda, tens of thousands of children have been abducted, 1.6 million people herded into camps and thousands of people killed

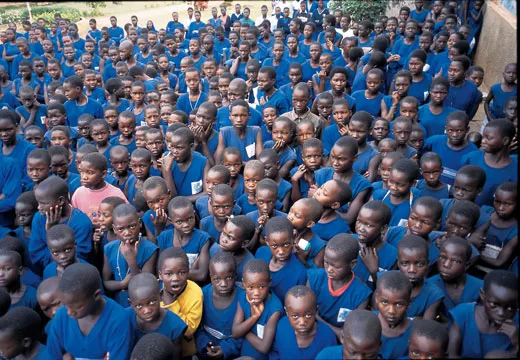

As the light faded from the northern Ugandan sky, the children emerged from their families’ mud huts to begin the long walk along dirt roads to Gulu, the nearest town. Wide-eyed toddlers held older kids’ hands. Skinny boys and girls on the verge of adolescence peered warily into roadside shadows. Some walked as far as seven miles. They were on the move because they live in a world where a child’s worst fears come true, where armed men really do come in the darkness to steal children, and their shambling daily trek to safety has become so routine there’s a name for them: “night commuters.”

Michael, a thin 10-year-old wrapped in a patched blanket, spoke of village boys and girls abducted by the armed men and never seen again. “I can’t get to sleep at home because I fear they’ll come and get me,” he said.

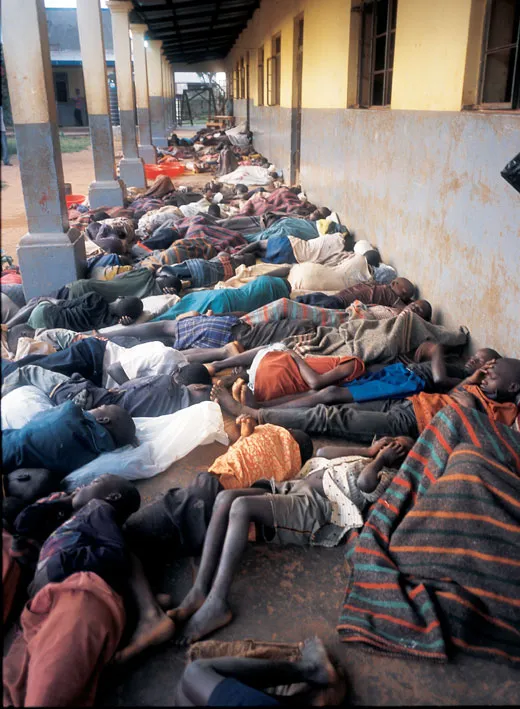

Around the time of my trip to northern Uganda this past November, some 21,000 night commuters trudged each twilight into Gulu, and another 20,000, aid workers said, flocked into the town of Kitgum, about 60 miles away. The children, typically bedding down on woven mats they’d brought with them, packed themselves into tents, schools, hospitals and other public buildings serving as makeshift sanctuaries that were funded by foreign governments and charities and guarded by Ugandan Army soldiers.

The children were hiding from the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a murderous cult that has been fighting the Ugandan government and terrorizing civilians for nearly two decades. Led by Joseph Kony, a self-styled Christian prophet believed to be in his 40s, the LRA has captured and enslaved more than 20,000 children, most under age 13, U.N. officials say. Kony and his foot soldiers have raped many of the girls—Kony has said he is trying to create a “pure” tribal nation—and brutally forced the boys to serve as guerrilla soldiers. Aid workers have documented cases in which the LRA forced abducted children to ax or batter their own parents to death. The LRA has also killed or tortured children caught trying to escape.

LRA rebels roam northern Uganda’s countryside in small units, surfacing unpredictably to torch villages, kill people and kidnap children before returning to the forest. The LRA’s terror tactics and the bloody clashes between the rebels and the army have caused 1.6 million people, or about 90 percent of northern Uganda’s population, to flee their homes and become refugees in their own country. These “internally displaced” Ugandans have been ordered to settle in squalid government camps, where malnutrition, disease, crime and violence are common. The international medical aid group Doctors Without Borders said recently that so many people were dying in government camps in northern Uganda that the problem was “beyond an acute emergency.”

Word of the tragedy has surfaced now and then in Western news media and international bodies. U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan has called for an end to the violence in northern Uganda, and the U.N. has also coordinated food donations and relief efforts in Uganda. “The LRA’s brutality [is] unmatched anywhere in the world,” says a 2004 U.N. food program booklet. But the Ugandan crisis has been largely overshadowed by the genocide in neighboring Sudan, where nearly 70,000 people have been killed since early 2003 in attacks by government-supported Arab militias on the black population in the Darfur region.

The U.S. State Department classifies the LRA as a terrorist organization, and in the past year the United States has provided more than $140 million to Uganda; much of that is for economic development, but the sum includes $55 million for food and $16 million for other forms of assistance, such as AIDS education efforts and support for former child soldiers and formerly abducted persons. In May 2004, Congress passed the Northern Uganda Crisis Response Act, which President Bush signed in August. It does not provide for funding but urges Uganda to resolve the conflict peacefully and also calls for the State Department to report on the problem to Congress this month.

Despite some growing awareness of the crisis and recent small increases in assistance to Uganda from many nations and aid organizations, Jan Egeland, the U.N.’s Under Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs, said in a press conference this past October that the chaos in northern Uganda is the world’s “largest neglected humanitarian emergency.” He went on, “Where else in the world have there been 20,000 kidnapped children? Where else in the world have 90 percent of the population in large districts been displaced? Where else in the world do children make up 80 percent of the terrorist insurgency movement?”

To spend time in northern Uganda and learn firsthand about the situation is to become horrified by the atrocities and appalled by the lack of effective response. “The tragedy here is that it’s not an adult war, this is a children’s war, these kids are 12, 13, 14 years old and it’s despicable, beyond comprehension,” says Ralph Munro, who was visiting Gulu (while I was there) as part of a U.S. Rotarian mission to deliver wheelchairs to the war zone. “The world better wake up that this is another holocaust on our hands, and we’d better deal with it. One day our kids are going to be asking us, where were you when this was going on?”

Since achieving independence from Britain in 1962, Uganda has suffered almost uninterrupted brutality. Armed rebellions, mostly split along ethnic lines, have wracked the population, now estimated at 26.4 million. Up to 300,000 people were murdered during Idi Amin’s eightyear (1971 to 1979) reign of terror. It is said that Amin, who died a year and a half ago in exile in Saudi Arabia, ate some of his opponents and fed others to his pet crocodiles. “His regime goes down in the scale of Pol Pot as one of the worst of all African regimes,” says Lord Owen, who was the British foreign secretary during Amin’s rule.

Today, many Western governments regard Uganda as a qualified success from a development standpoint. It has made significant progress against AIDS, promoting condom use and other measures; since the mid-1990s, the prevalence of AIDS cases among Ugandans 15 to 49 years old has fallen, from 18 percent to 6 percent. Still, AIDS remains the leading cause of death of people in that age group. Many countries, including the United States, have applauded the willingness of soldier-politician Yoweri Museveni, the president since 1986, to accede to World Bank and International Monetary Fund dictates on free trade and privatization. Uganda claims a 6.7 percent average annual economic growth over the past ten years.

But that growth is largely confined to the south and Kampala, the capital city, which boasts office towers, fancy restaurants and flashy cars. Elsewhere, deep poverty is the rule. With a per capita income of $240, Uganda is among the world’s poorest countries, with 44 percent of citizens living below the national poverty line. The nation ranks 146th out of 177 countries on the U.N.’s Human Development Index, a composite measure of life expectancy, education and living standard. Donor countries and international lending agencies cover half of Uganda’s annual budget.

Museveni heads a corrupt regime in a nation that has never seen a peaceful change of rule. He seized power at the head of a guerrilla army in a violent coup 19 years ago, and he has since stage-managed two elections. The U.S. State Department calls Uganda’s human rights record “poor” and charges in a 2003 report that Museveni’s security forces “committed unlawful killings” and tortured and beat suspects “to force confessions.”

Museveni’s suppression of the Acholi tribal people, who populate three northern districts, is generally cited as the catalyst of the LRA rebellion. Museveni, a Christian, is a member of the Banyankole tribe, from western Uganda, and the Acholi blame him for atrocities his forces committed when they came to power and for denying the region what they say is their share of development funds. In 1986, an Acholi mystic, Alice Auma “Lakwena,” led a rebel army of some 5,000 aggrieved Acholis to within 50 miles of Kampala before being defeated by regular army forces. (She fled to Kenya, where she remains.) A year later, Joseph Kony—reportedly Lakwena’s cousin—formed what would become the Lord’s Resistance Army and pledged to overthrow Museveni. Since then, thousands of people have been killed in the conflict—no exact casualty figures have been reported—and it has cost the impoverished nation at least $1.3 billion.

It takes four hours, including a crossing of the roiling, whitecapped waters of the NileRiver as it plunges toward a waterfall, to drive from Kampala to Gulu. Nearing the city, villages begin to disappear, replaced by vast, dreary government camps. Gulu is a garrison town, home to the Ugandan Army’s battle-hardened 4th Division, and soldiers with assault rifles stroll along potholed footpaths or drive by in pickup trucks. Crumbling shops built of concrete line the main road. The day before I arrived, LRA fighters, in a trademark mutilation, cut off the lips, ears and fingers of a camp dweller two miles from the city center. His apparent crime was wearing the kind of rubber boots favored by government soldiers, arousing LRA suspicion that he might be one himself. The LRA went on to attack a refugee camp along

Kampala Road

, 15 miles away, abducting several children. Over the years, about 15,000 of the children abducted by the LRA have managed to escape or have been rescued by Ugandan Army forces, says Rob Hanawalt, UNICEF’s chief of operations in Uganda. Many former abductees are brought to Gulu, where aid organizations evaluate them and prepare them to return to their home villages.

The Children of War Rehabilitation Center, a facility run by World Vision, an international Christian charity, was hidden behind high shuttered gates, and walls studded with broken glass. Inside, one-story buildings and tents filled the small compound. At the time of my visit, 458 children were awaiting relocation. Some kicked a soccer ball, some skipped rope, others passed the time performing traditional dances. I saw about 20 children who were missing a leg and hobbling on crutches. One could tell the most recent arrivals by their shadowy silences, bowed heads, haunted stares and bone-thin bodies disfigured by sores. Some had been captured or rescued only days earlier, when Ugandan Army helicopter gunships attacked the rebel unit holding them. Jacqueline Akongo, a counselor at the center, said the most deeply scarred children are those whom Kony had ordered, under penalty of death, to kill other children. But virtually all the children are traumatized. “The others who don’t kill by themselves see people being killed, and that disturbs their mind so much,” Akongo told me.

One evening in Gulu at a sanctuary for night commuters, I met 14-year-old George, who said he spent three years with the rebels. He said that as the rebels prepared to break camp one night, a pair of 5-year-old boys complained that they were too tired to walk. “The commander got another young boy with a panga [machete] to kill them,” George said. On another occasion, George went on, he was forced to collect the blood of a murdered child and warm it in a saucepan over a fire. He was told to drink it or be killed. “‘It strengthens the heart,’” George recalled the commander telling him. “ ‘You then don’t fear blood when you see somebody dying.’ ”

In Gulu I met other former abductees who told equally ghastly tales, and as unbelievable as their experiences may seem, social workers and others who’ve worked in northern Uganda insist that the worst of the children’s reports have been found to be literally true. Nelson, a young man of about 18, stared at the ground as he described helping to beat another boy to death with logs because the boy had tried to escape. Robert, a 14-year-old from Kitgum, said he and some other children were forced to chop the body of a child they had killed into small pieces. “We did as we were told,” he said.

Margaret, a 20-year-old mother I met at the rehabilitation center in Gulu, said she was abducted by LRA forces when she was 12 and repeatedly raped. She said that Kony has 52 wives and that 25 abducted girls will become his sexual slaves once they reach puberty. Margaret, a tall, softvoiced woman with faraway eyes who that day held her 4-year-old son in her lap, said she was the eighth wife of a high-ranking LRA officer killed in a battle last year. Sixteen year-old Beatrice cradled her 1-year-old infant as she recalled her forced “marriage” to an LRA officer. “I was unwilling,” she tells me, “but he put a gun to my head.”

People describe Kony’s actions as those of a megalomaniac. “Kony makes the children kill each other so they feel such an enormous sense of shame and guilt that they believe they can never go back to their homes, trapping them in the LRA,” said Archbishop John Baptist Odama, the Roman Catholic prelate in Gulu and head of the Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative, a Christian and Muslim organization trying to broker an end to the hostilities.

The highest-ranking LRA member in government custody is Kenneth Banya, the rebel group’s third in command. He was captured this past July after a fierce battle near Gulu. One of his wives and a 4-year-old son were killed by helicopter gunship fire, but most of his 135 soldiers got away. Today Banya and other captured LRA officers are held at the government army barracks in Gulu. The army uses him for propaganda, having him speak over a Gulu radio station and urge his former LRA colleagues to surrender.

Banya is in his late 50s. When I met him at the barracks, he said he underwent civilian helicopter training in Dallas, Texas, and military training in Moscow. He claimed that he was himself abducted by LRA fighters, in 1987. He said he advised Kony against abducting children but was ignored. He denied that he ever ordered children to be killed or that he had raped young girls. Banya said that when he arrived at his first LRA camp, water was sprinkled on his bare torso and rebels marked him with crosses of white clay mixed with nut oil. “ ‘That removes your sins, you’re now a new person and the Holy Spirit will look after you,’ ” he recalled of his indoctrination.

When I relayed Banya’s comments to Lt. Paddy Ankunda, spokesman for the government’s northern army command, he laughed. Banya, he said, crossed over to Kony of his own volition. Agovernment handout issued at the time of Banya’s capture described him as the “heart and spirit” of the LRA.

The terrorist forces led by Kony, an apocalyptic Christian, could not have flourished without the support of the radical Islamic Sudanese government. For eight years beginning in 1994, Sudan provided the LRA sanctuary—in retaliation for Museveni’s backing a Sudanese Christian rebel group, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, which was fighting to gain independence for southern Sudan. The Khartoum government gave Kony and his LRA weapons, food and a haven near the southern Sudan city of Juba. There, safe from Ugandan government forces, Kony’s rebels sired children, brainwashed and trained new abductees, grew crops and regrouped after strikes in Uganda. “We had 7,000 fighters there then,” Banya told me.

In March 2002, the Sudanese government, under pressure from the United States, signed a military protocol with Uganda that allowed Ugandan troops to strike the LRA in southern Sudan. The Ugandan Army quickly destroyed the main LRA camps in Sudan. Kony then stepped up raids and abductions in Uganda’s north; according to World Vision, LRA forces captured more than 10,000 children in Uganda between June 2002 and December 2003.

It was around then that Museveni ordered the Acholi population into the relative safety of government camps. “In April 2002 there were 465,000 in the camps displaced by the LRA,” says Ken Davies, director of the U.N.’s World Food Program (WFP) in Uganda. “By the end of 2003 there were 1.6 million in the camps.” At last count, there were 135 government camps. In my three decades of covering wars, famines and refugees, I have never seen people forced to live in more wretched conditions.

In a convoy of trucks filled with WFP rations, and accompanied by some 100 armed Ugandan Army soldiers and two armored vehicles mounted with machine guns, I visited the Ongako camp, about ten miles from Gulu.

Ongako housed 10,820 internally displaced persons. Many wore ragged clothing as they waited for food in long lines in a field near hundreds of small conical mud huts. The crowd murmured excitedly as WFP workers began unloading the food—corn, cooking oil, legumes and a corn and soybean blend fortified with vitamins and minerals.

Davies told me that the WFP provides camp dwellers with up to three-quarters of a survival diet at an average cost of $45 a year per person, about half of it supplied by the U.S. Agency for International Development. The displaced are expected to make up the difference by raising crops nearby. The Ugandan government provides little food for the camps, Davies said. The leader of the camp residents, John Omona, said there is not enough food, medicine or fresh water. More than half of the camp residents are children, and World Vision officials say that as many as one out of five suffer from acute malnutrition. When I was there, many bore the swollen bellies and red-tinged hair of kwashiorkor, a disorder brought on by extreme protein deficiency, and I was told that many had died from starvation or hunger-related diseases. “The extent of suffering is overwhelming,” Monica de Castellarnau of Doctors Without Borders said in a statement.

Benjamin Abe—a native Ugandan, an Acholi and an anthropologist at North Seattle Community College—said he was horrified by his recent visit to a displaced persons camp near Gulu. “It was inhumane, basically a concentration camp,” he said when we met last November in Kampala.

Compared with the open countryside where LRA terrorists may remain at large, the government camps are a refuge, but people in the camps say they, too, are preyed upon, as I learned during an unauthorized visit to campAwer, 13 miles from Gulu. Awer nudged the roadside, a gigantic huddle of thousands of small conical family huts. The air was sour with the smell of unwashed bodies, poor sanitation and sickness. Men slouched in the shade of their huts or played endless games of cards. Children squatted on bare earth in mud-hut classrooms, with neither pencils nor books. Exhausted-looking women cooked meager meals of maize or swept the dust from family hearths.

About 50 men and women gathered around me. Many of the men bore scars—on their legs, arms and head—that they said came from torture by government soldiers. Grace, who said she is in her 30s but looked 20 years older, told me that a Ugandan government soldier raped her at gunpoint three years ago as she was returning to the camp after taking her child to the hospital. “It’s very common for soldiers to rape women in the camp,” she added. Her attacker had since died of AIDS, she said. She didn’t know if she had the virus that causes the disease.

The U.N.’s Hanawalt said that young women in the camp avoid going to the latrines at night out of fear of being raped by government soldiers or other men. One camp leader told me that the AIDS rate in the camp was double that in the rest of Uganda.

In 2000, Museveni, to draw the rebels (and their captives) out of the bush, began offering amnesty to all LRA members, and some have taken advantage of the offer, though not Kony. Then, in January 2004, the president complicated the amnesty offer by also inviting the International Criminal Court into Uganda to prosecute LRA leaders for war crimes. The human rights group Amnesty International supports the move to prosecute Kony and other LRA leaders.

But Anglican bishop Macleord Baker Ochola, vice chairman of the Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative, opposes prosecution. He says it would ruin any chance for a peaceful resolution and would amount to a double standard unless government soldiers were also prosecuted for their crimes, including, he said, the rape and murder of civilians. Ochola argues for granting LRA members amnesty, even though he says an LRA land mine killed his wife and LRA rebels raped his daughter, who later committed suicide.

Many aid workers advocate a peaceful settlement. “There is no military solution to the violence and insurgency in the north,” the U.N.’s Egeland wrote last fall. One drawback of a military approach, critics say, is the high casualty rate among LRA captives. Relief workers have condemned the army’s use of helicopter gunships to fight LRA units because women and children are killed along with the rebel soldiers. The Ugandan Army defends the practice. “The LRA train their women and children to use rifles and even rocket-propelled grenades, and so we shoot them before they shoot us,” Maj. Shaban Bantariza, the army spokesman, told me.

This past November, Museveni declared a limited ceasefire zone in northern Uganda between the government and LRA forces. In late December, internal affairs minister Ruhakana Rugunda and former government minister Betty Bigombe led a group, including Odama and U.N. representatives, that met with LRA leaders near the Sudan border to discuss signing a peace agreement by the end of the year. But the talks broke down at the last minute, reportedly after the government declined the LRA’s request for more time. President Museveni, speaking at a peace concert in Gulu on New Year’s Day, said the cease-fire had expired and vowed that the army would “hunt for the LRA leaders, especially Joseph Kony . . . and kill them from wherever they are if they don’t come out.” He also said: “We have been slow in ending this long war,” although, he added, 4,000 child captives had been rescued since August 2003.

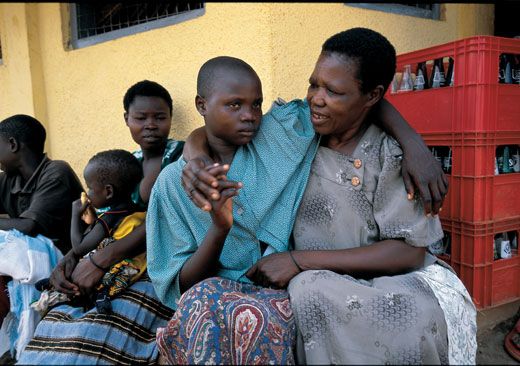

At a holding center run by a Catholic relief organization in the northern Uganda town of Pader, ten young mothers and their babies were preparing to go home. They’d flown there from Gulu in a UNICEF-chartered plane. Among the young women was Beatrice, and as soon as she walked into the building a teenage girl rushed up to her. “You’re alive!” the girl screamed, high-fiving Beatrice.

“We were best friends in the bush,” Beatrice told me. “She thought I’d been killed by the gunships.”

Such reunions are typically happy affairs, but formerly abducted children face a grim future. “They’ll need counseling for years,” Akongo said, adding there’s little or no chance of their getting any.

One day at the Children of War Rehabilitation Center in Gulu, I saw Yakobo Ogwang throw his hands in the air with pure glee as he ran to his 13-year-old daughter, Steler, seeing her for the first time since the LRA abducted her two years before. “I thought she was dead,” he said in a shaking voice. “I’ve not slept since we learned she’d returned.” The girl’s mother, Jerodina, pulled Steler’s head to her bosom and sobbed. Steler stared silently at the ground.