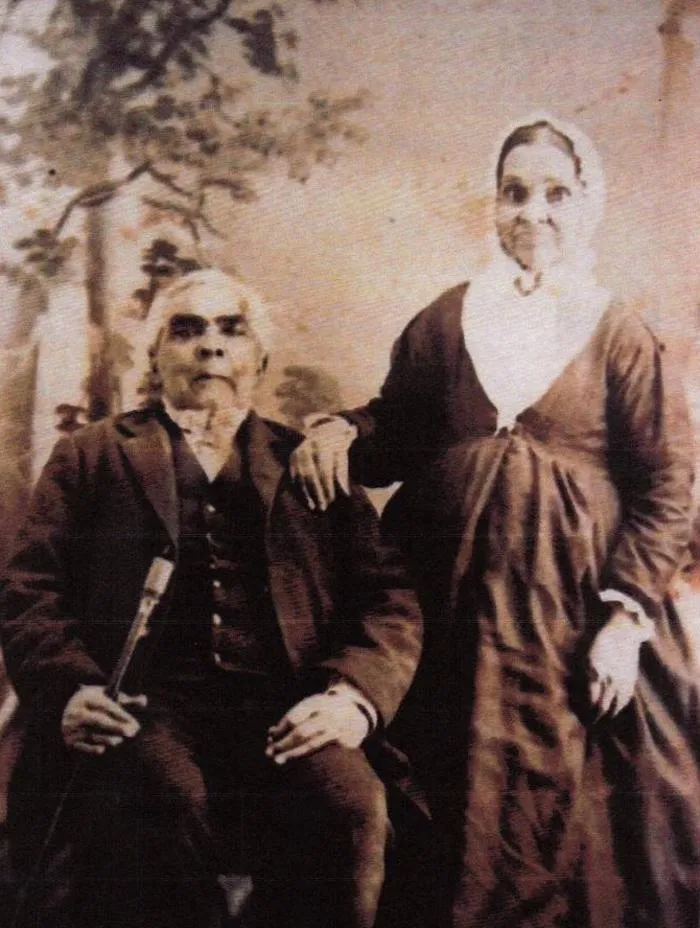

The Unheralded Pioneers of 19th-Century America Were Free African-American Families

In her new book, ‘The Bone and Sinew of the Land’, historian Anna-Lisa Cox explores the mostly ignored story of the free black people who first moved West

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/d7/f0d7fa8b-5563-4d33-aaa8-f0fbbbdb9653/nw_territory_1787.jpg)

Before the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, before settlers in wagons organized to travel west along the Oregon Trail in the 1830s, the great American frontier was the prized stretch of land, comprising the states we know today as Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin. The colonial rebels claimed control of the region, known as the “Northwest Territory,” upon the end of the American Revolution in 1783. In fact, that territory was one of the reasons for going to war in the first place; British colonists wanted to settle there and turn it to farmland, while George III hoped to leave it for Native Americans and fur trading companies.

When the newly formed United States government opened the territory up for purchase by citizens, ignoring indigenous populations’ right to the land, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 also stipulated that the region would be free of slavery and that any man who owned at least 50 acres of land, regardless of skin color, could vote. By 1860, the federal census found more than 63,000 African-Americans living in the five states that were founded out of that territory; 73 percent of them lived in rural areas. Those people are the focus in The Bone and Sinew of the Land: America’s Forgotten Black Pioneers and the Struggle for Equality by Harvard historian Anna-Lisa Cox.

“When I started this project, the assumption was that there were three, maybe five settlements where landowning African-American farmers lived in the Midwestern states,” Cox says. “What I began to realize as I studied these settlements and found more and more of them is that it’s these pioneers who had such courage and such imagination about what the nation should be and could be. And it was probably historians, myself included, who were lacking in imagination about this region.”

The Bone and Sinew of the Land: America's Forgotten Black Pioneers and the Struggle for Equality

The Bone and Sinew of the Land tells the lost history of the nation's first Great Migration. In building hundreds of settlements on the frontier, these black pioneers were making a stand for equality and freedom.

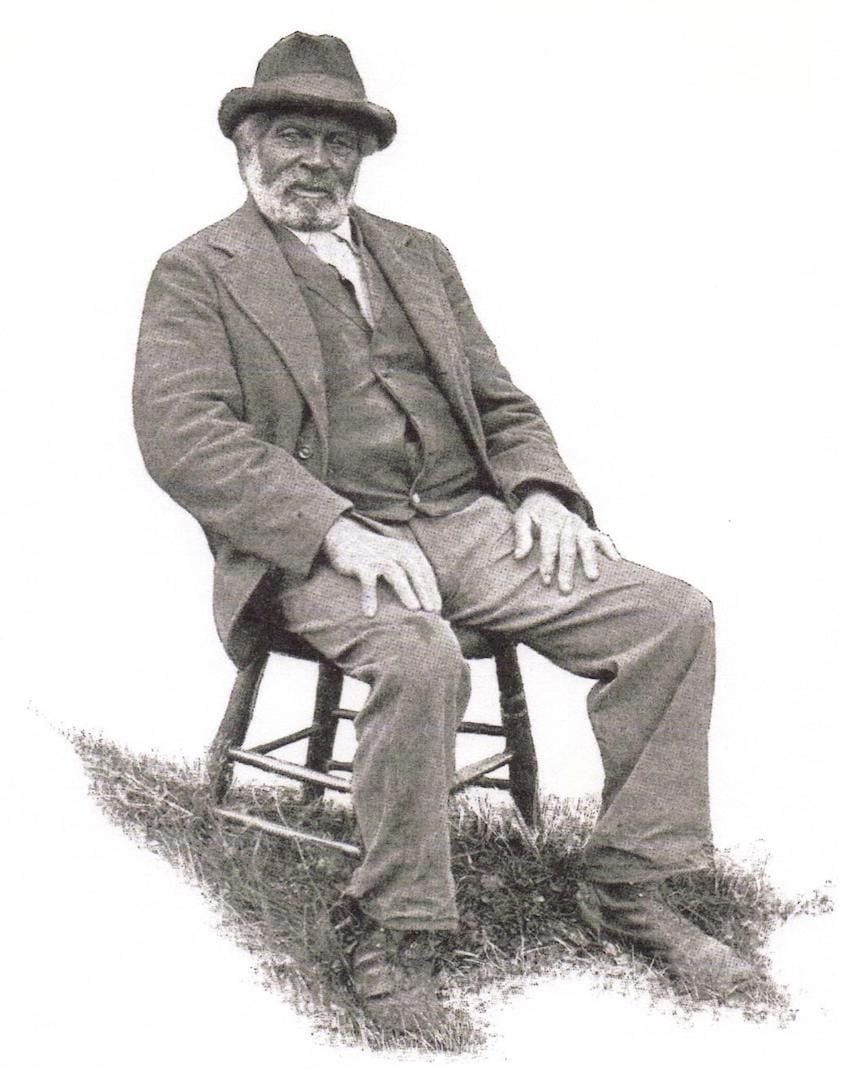

Cox immersed herself in the archives of rural county court houses, poring through 200-year-old deed books, poking around the basements of libraries. What she found seemed to overturn so many supposed knowledge about the early texture of the United States. Not only was the Northwest Territory home to numerous free black communities (which included both formerly enslaved persons, and African-Americans born free), it also saw the rise of integrated churches and schools long before those issues were tackled during the Civil Rights movement of the 20th century. For years, African-American men had the right to vote in these places; they could purchase land, own guns, even purchase the freedom of their enslaved family members. In 1855, John Langston became the first African-American in the country to hold elected office; he was voted town clerk by a community of white and black citizens in Ohio.

That history remained hidden for decades in part due to what came next: a violent backlash that forced many African-Americans from their homes, and endangered their lives if they revealed themselves on the national census, lasting from the 1830s well into the years following the end of the Civil War.

To learn more about those early pioneers, the challenges they faced, and how they shaped the nation, Smithsonian.com spoke with author Anna-Lisa Cox.

In your book, you describe the migration of Americans into the Northwest Territory as “one of the largest movements of human beings from one region of the planet to another.” Can you talk about what made the region so unique in the context of the new United States?

I really want to say [at the outset], at the same time as this history is happening there is genocide, there is terrible violence, and the rights of [Native Americans], whose homeland this is, are being absolutely devastated. This is not an uncomplicated space, even from the beginning.

Today we think of this region as the flyover zone, but at one point this was the nation’s frontier, this was its first free territory. This was rich farmland seen as a wonderful space to buy good land for cheap and start your farm on it. At this time, the American dream was to own good land and farm it well. Neither one of those things are easy, and doing it on the frontier is one of the hardest things you could possibly do.

Of course, African-American pioneers were facing hurdles that were so much higher than white pioneers [including having to prove they were free and paying up to $500 to show they wouldn’t be a financial burden on new communities]. Over and over again I would come across stories about whites arriving in a region to find African-American settlements already there, and sometimes even turning to some of those most successful African-American farmers for help, learning how to farm well in that region, what plants were poisonous, where you could let your hogs run and where you could let your cows graze, that kind of thing.

Those free African-American farming communities seem so different from what’s historically been presented. What appealed to these people to settle in the countryside instead as opposed to cities?

It’s one of the reasons why this movement hasn’t been researched for so long. There’s been a long assumption that African-Americans in the north were primarily urban. I was interested in exploring the perception that cities were the great melting pot, where people were figuring out how to live together and struggling for equal rights, and that the rural areas were the backwards, conservative ones. This entire dichotomy falls apart when you look at the Northwest territorial frontier.

By the 1830s and 1840s, there was space in this region, despite its racist legislation and laws, where people really were living together as neighbors, some truly harmoniously, others just tolerantly. At a time where in the Northeast, it had become impossible to open a school for African-Americans and so many things had become impossible, they were still possible in the rural and farming Midwest. Maybe it’s because people really were “conservative,” maybe they were holding onto those old notions that came up from the early Republic.

The Union Literary Institute [in Randolph County, Indiana] is one of my favorite examples. It was a pre-collegiate boarding school for teenagers, white and black, girls and boys, and had an integrated board, and an African-American president. So this is not about white paternalism, this is about African-American agency.

How did this region live up to the ideals of the Revolution?

The vast majority of the states and the Northwest ordinance in 1792 had equal voting rights among men. A whole lot of people were saying in the 1780s and 1790s, if we’re going to make this experiment work we can’t have the tyranny of slavery, and we have to have as much equality as possible. If we allow the poison of prejudice to infect the politics and laws of this nation, then we are weakening our democratic republic.

A couple of politicians described prejudice laws as being so nonsensical because they’re based on difference in hair follicles. If you’re willing to create a law keeping somebody from their citizenship rights for something as foolish as their hair follicles, then the danger of that is you could open that up to anybody or anything. At any point you could decide to exclude any group of people from citizenship, who is to belong, who is considered not to belong, who is considered an American, who is considered not an American.

I’ve heard people argue that we cannot fault whites who lived before the Civil War for being racist or enslaving people, they couldn’t have known any better, their paradigm made them innocent. But there has never been a time in this nation when there hasn’t been a very loud voice from both African-American and whites saying no, slavery is tyranny. Slavery and prejudice are an anathema to American values.

What kinds of struggles did African-American settlers face in the Northwest Territory?

[Many] were just normal people wanting to live normal lives when to live a normal life took heroic actions. I can’t imagine the kind of courage it took for somebody like Polly Strong [who was held in slavery despite it being illegal] to stand up to the man who was enslaving her and threatening her, to overcome slavery in the entire state of Indiana [in an 1820 court case]. Or Keziah Grier and her husband, Charles, who had experienced in their bodies what enslavement was like and were willing to risk the farm that they had homesteaded and created and even the safety of their own family to help other people other families also have freedom [on the Underground Railroad].

Then there’s an example in Indiana in the 1840s where the largest mill owner in the county was African-American, and he was doing a service in that area. But whites who came after him literally drove him out at the point of a gun. Then they lost the mill and a skilled miller.

Racism arose in the face of African-American success, not African-American failure. One of the hard parts about this history, is that something astounding happened in this region before the Civil War, and then something very terrible happened as well. We need both parts of that story to truly understand the American past.

Some of those terrible things included voting rights for African-Americans being rescinded, and “Black Laws” put into place. Then the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 meant people in the Northwest Territory were required to return the people that escaped slavery, and then the 1857 Dred Scott decision ruled no black person could be a citizen. How did all that come about?

The young Abraham Lincoln actually says this in his first published speech ever in the 1830s. He addresses the violence that’s arising against African-Americans and he says, maybe it’s because as the old pillars of the Revolution fall away and die, maybe the next generation wants to do something different. Maybe that something different is hierarchal mob violence and being unfair to people.

Pro-prejudice organizers were using the language of insiders and outsiders, of those who belong and those who didn’t. They were constantly arguing that prejudice and hierarchy were the conservative, old core values of America. Highly organized mobs funded and organized by some of the most elite men in their community, often led by these men, sheriffs and mayors, college-educated people, were going and destroying printing presses and tarring and feathering or trying to lynch newspaper editors [who argued for equality and abolition]. It was in the 1830s that the notorious gag rule occurred in the federal government where [politicians] literally would not speak the words of freedom. Any petition about ending slavery was gagged [by the federal government].

If there’s anything we can learn from history it’s not just one upward trajectory. It’s more like an old river that winds back on itself and gets lost in swamps and then goes forward a little bit, then winds back.

Many histories of this period focus exclusively on the evils of slavery, the attempts of enslaved people to escape, and not the hardship faced by free African-Americans. Do you think that’s part of why so much has been forgotten?

There were two important oppositional struggles going on before the Civil War. One was slavery versus freedom, the other was equality versus inequality. They were of course intertwined and interlinked but they were also separate. Unfortunately, the slavery-versus-freedom one seems to have become paramount in the way that we think about the 19th century. But if we lose the discussion that was occurring about equality versus inequality that was also forefront in people’s minds before the Civil War, then we lose a very basic way of understanding what we’re struggling with today.

It is a shame that this history has been buried for so long. And it is an active burying. I’m aware of a number of situations where the work to preserve the homes and the buildings left behind by these pioneers and their allies is being strongly opposed. The actual physical remnants on the landscape of this history are being destroyed or allowed to crumble. If we allow the last building of the Union Literary Institute to crumble [which is happening now], then it’s much harder to preserve that history. John Langston’s home was allowed to fall down, when he was the first African-American to be elected into political office in the United States.

There’s ways in which the way that we choose to be blind to certain aspects of our past. It’s like we keep poking ourselves in the eye. It’s a terrible image, but it’s an act of violence to keep ourselves blind.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)