What the Unisphere Tells Us About America at the Dawn of the Space Age

A towering tribute to the future past—and one man’s ego

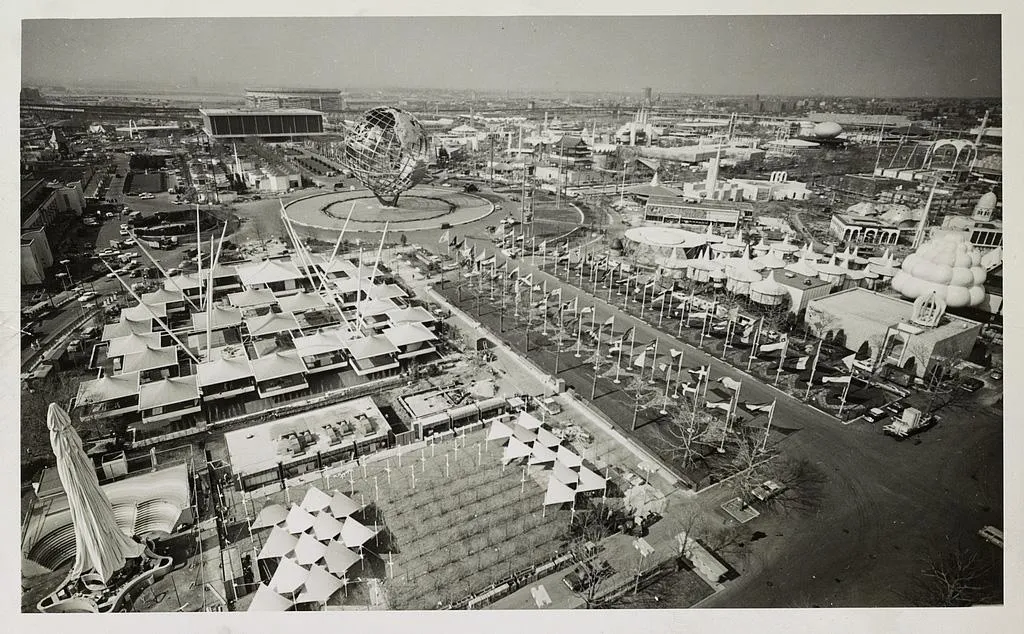

In the 1930s, Robert Moses, the great builder of New York’s public works, converted a marshy garbage dump into Flushing Meadows, site of the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The futurist extravaganza was remembered for its Trylon, a needle-thin obelisk, and the spherical Perisphere, gleaming symbols of the American century. In 1960, Moses was gearing up for a second fair in the same spot, and he wanted something just as compelling, a monument to his legacy that would convince the city to change the name of Flushing Meadows to Robert Moses Park. He sent a memo to his designers asking for some kind of “understandable abstraction.” Maybe something electronic. Or a bridge. Moses built a lot of bridges.

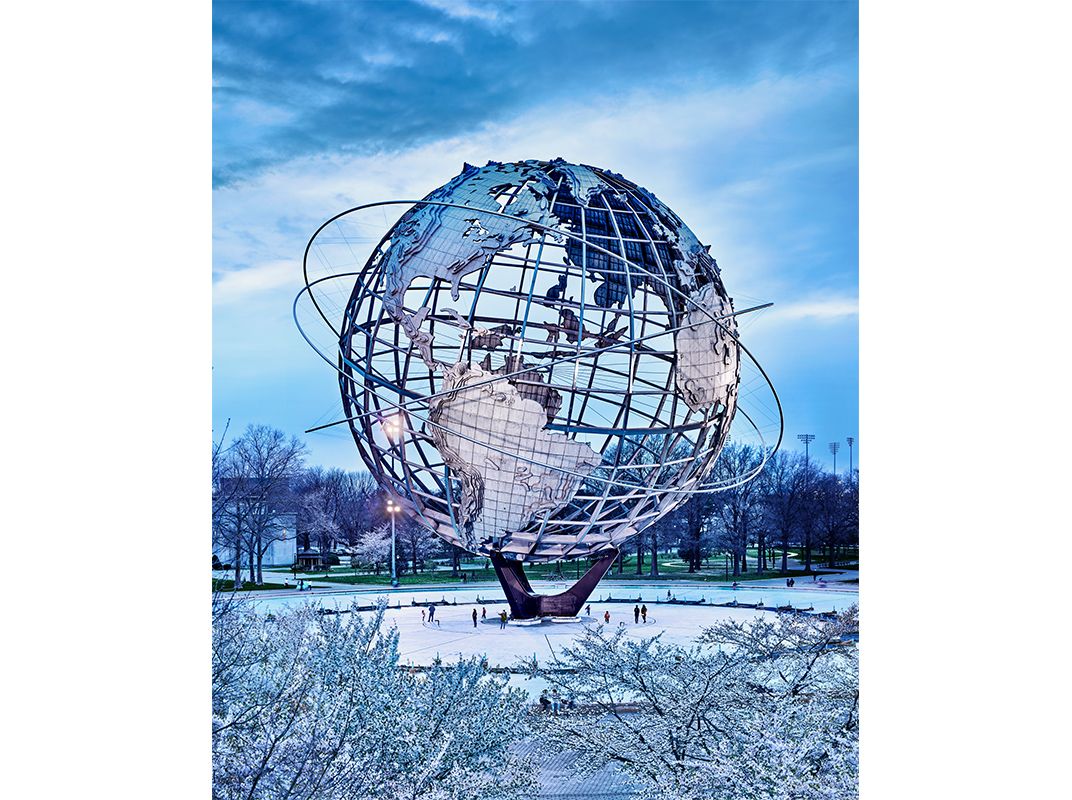

After rejecting a spiraling observation tower that Moses said looked like a bedspring, he saw a sketch that Gilmore Clarke, a park designer and longtime colleague of Moses, had made on the back of an envelope—no kidding—of a 12-story-tall metal armillary. This skeletal Earth was ringed by the tracks commemorating Yuri Gagarin’s Vostok spacecraft, John Glenn’s Friendship 7 and the Telstar satellite: the three human-made things that had gone into orbit up until that point. The Unisphere, as they named it, would be “of the space age,” Moses said at its dedication, “built to remain as a permanent feature of the park, reminding succeeding generations of a pageant of surpassing interest and significance.”

Like the Eiffel Tower and Seattle’s Space Needle, those other world’s fair leftovers, the Unisphere was an engineering achievement. Together the base and globe weigh 450 tons; they sit atop the lumber pilings that supported the earlier Perisphere—plus 600 more, jammed 100 feet into the sodden, garbagey soil. The globe’s continents, which act like parachutes in the wind and must be able to stand up to hurricanes and corrosion alike, were made of stainless steel from U.S. Steel. The stresses and strains on the metal were so complicated that only—gasp!—electronic computers could calculate them. The Unisphere became the space age logo of the fair, a steel Earth at the Ptolemaic hub of a Googie-style Jetsons universe.

But the Unisphere was as much a pivot in time as in space. President John F. Kennedy, who had begun the race to send a crewed mission to the Moon, was assassinated five months before the fair opened. U.S. Steel, a juggernaut since 1901, stopped growing in 1964. Four months after the fair started, the USS Maddox engaged with the Vietnamese Navy in the Gulf of Tonkin, widening U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Though the Apollo missions were yet to come, the high-flying dreams and the industrial might that propelled the space age were already in descent.

So was the age of Moses. The ’64 fair was a financial failure—its attendance of 51 million was nearly 20 million fewer than expected—and Moses’ peremptory management style (and $100,000-a-year salary) doomed him. “The great universal exposition that had been supposed to rehabilitate his popularity had instead destroyed the last of it,” Robert Caro wrote in The Power Broker, his biography of Moses. He lived until 1981, but he never really built again.

Yet it remains America’s best monument to that time when America was building the road to the future. Flushing Meadows-Corona Park still gets hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. Millions more, on their way to airports and baseball games, spy the Unisphere from highways Moses built. “Unisphere is very different from other retrofuture relics,” says Darran Anderson, author of Imaginary Cities. “They appeal because they optimistically promised us a world that sadly never came to pass. Moses’ vision of New York largely came true.”

And if the fair destroyed Moses, it helped create another great builder: Walt Disney. “All the big corporations in the country are going to be spending a helluva lot of money building exhibits there,” he told his team of “Imagineers” in 1960, according to Steven Watts’ book The Magic Kingdom. “They won’t know what they want to do.”

The Imagineers did, and ended up providing four attractions for various exhibitors, including a talking Abraham Lincoln that Moses fell in love with after it shook hands with him. (Moses secured $250,000 to pay for the Lincoln-bot to appear in Illinois’ pavilion.) When the fair ended, Disney adopted Lincoln and the “It’s a Small World” exhibit, in which mannequin children built for Unicef sang the ear-wormiest song ever written, for Disneyland. The technology developed for moving specially rigged Thunderbirds through the Ford exhibit drove the Haunted Mansion and People Mover rides.

If Moses’ hopes from 1964 live on, it’s in his dream of the perfectible American city. Success in New York convinced Disney to open a new park on the East Coast. It landed in Florida, eventually evolving into the never-ending world’s fair of Epcot and the new-urbanist town of Celebration. They might not be Moses’ vision exactly—not enough highways—but his fair gave rise to them all the same.

Related Reads

1964-1965 New York World's Fair, The (Images of America)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/d6/57d6cda6-2e9d-4dcc-8a66-d10ec927ac32/jun2017_h43_prologue.jpg)