On October 27, 1815, Prospect Robbins arrived by boat at the point in the alluvial swamps where the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers meet. He planted a post in the ground to mark his arrival, and then, along with his team, he began to trek into the muck.

On the same day, a second man, Joseph Brown, embarked with a separate team at another confluence: the mouth of the St. Francis River. Both surveyors were veterans—Brown a captain, Robbins a lieutenant—of an army that a few months earlier had been fending off a British invasion. Now, they were official emissaries of the United States government: here not just to scout the landscape but also to lay upon it a perfect rectilinear grid.

Decades earlier, Thomas Jefferson had formed a vision for new territory west of the Appalachian Mountains: It would fuel the creation of an “empire for liberty.” He first used a version of this phrase during the Revolutionary War, in a 1780 letter that urged George Rogers Clark, a surveyor turned soldier, to head north to wrest more land from the British. The frontiersman proved unable to muster sufficient recruits for an expedition, but Jefferson never dropped the idea.

After the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War in 1783, Britain ceded more territory that doubled the size of the U.S. Along with the original 13 colonies, the new country now included territory that stretched all the way to the Mississippi River, to the western edges of what would become Wisconsin, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee and the northern part of Mississippi. These new lands offered the space that Jefferson needed to establish an empire of landed farmers—“cultivators,” as he called them, or “husbandmen.” Jefferson did not want the soot-stained, over-mobbed cities that were growing like “sores” on the body of Europe. Nor was untamed nature a suitable fit for the new nation. He hoped the Mississippi watershed would be converted to a garden—or a collection of gardens, spreading across the landscape like a quilt. Private property would be everywhere. The only shared resource he spoke of was the river itself, the highway into his promised land.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/09/d5/09d5a09d-918d-4573-b00a-766c48a8b73b/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_263.jpg)

In the Land Ordinance of 1785, Jefferson came up with a plan for parceling out the new territory: Lay out a perfect grid of townships, each covering 36 square miles, which could be broken into 640-acre sections, then split again into 160-acre quarter sections. Rather than allow an unorganized tumble of men to pick lots on their whim, the whole empire would be cataloged, then sold at auctions in land offices established across the territories. With the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, this massive effort spread into the western watershed, through the 530 million new acres of land on the western side of the Mississippi River. And Robbins and Brown were instructed to establish the “initial point” for the era to come. They would cross the landscape at a right angle, with Robbins headed north, Brown headed west. The coordinates of every parcel within the new territories would be measured in reference to the spot where their lines intersected—the beginning, then, from which the river’s great wilderness would be tamed into a map.

Brown and Robbins assembled teams of men to serve as chainmen and axmen and markers. They were instructed by their superiors to leave late in the year, so as to avoid the “inundations, the undergrowth, weeds and flies of various descriptions.” (“No mortal man could take the woods before October,” one official added.) They slept in tents and lugged drinking water in pails. These frontiersmen knew how to hunt in these forests, what gear to carry, how to create quick shelter. But don’t picture grizzled mountaineers in stinking buffalo robes. These men were well educated—the polite, churchgoing neighbors down the block. Robbins was a former schoolteacher. It’s just that in this era, in this place, you needed to be hardy to make something of yourself.

As they trudged through the Arkansas swamps, they lugged chains to measure their progress, marking their passage at half-mile intervals, typically by driving stakes into the muddy ground. At the end of each mile, they selected some stout trunk and carved a mark to make a “witness tree,” the corner of a new future parcel. On November 10, after two weeks in the wet forests—plodding forward just four miles on average each day—Robbins must have spied some sign of Brown’s passage. He slashed two trees, indicating the point where the two lines crossed. The initial point was set.

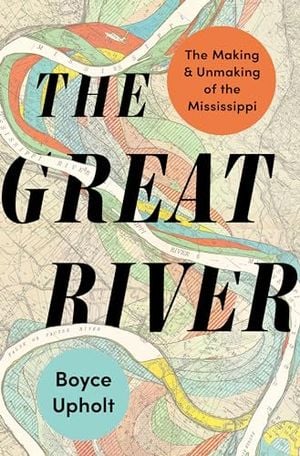

The Great River: The Making and Unmaking of the Mississippi

A sweeping history of the Mississippi River―and the centuries of human meddling that have transformed both it and America.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/7c/7c7ce50a-d4cc-47ad-9df0-608e9e6a8c6d/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_206.jpg)

Robbins wrapped up his assignment two months later, hundreds of miles north, on the banks of the Missouri River in the Ozark hills. Brown traveled on across the flood plain to reach the Arkansas River. But in all of the states that would emerge from the Louisiana Purchase, as far away as Montana and Minnesota, parcels would be oriented around these trees.

Not that the initial point had much to recommend itself. Brown described the terrain around the site as “low,” featuring “cypress and briers and thickets in abundance.” He seemed unimpressed, repeatedly describing this flood plain territory as second-rate land. Robbins, too, had his doubts: When his former general offered him a patch of the Arkansas flood plain as “war bounty,” the surveyor declined, figuring it would be too much work to wring out a profit. No one else was much impressed, either: More than 100 years later, no village had been built along his route.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/b2/61b24b70-a8d8-4772-b801-fd57fdb69d10/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_213.jpg)

In the 1920s, a new group of surveyors arrived, in an attempt to clarify the local county boundaries. As they hacked through the overgrowth, they noticed Robbins’ slashed trees—and realized what they’d found. The locals decided to preserve this place, so today it remains a tiny island of swamp amid a surrounding sea of soybeans, a little-visited state park. A boardwalk allows visitors to navigate across the wet soils to the place where, according to an official placard, “the settlement of the American West began.”

Prospect Robbins, born in Massachusetts, might have balked at the idea that he was only just reaching the west. Even Pittsburgh was considered part of the “western waters,” the jumping-off point for many journeyers headed downstream. There in Pittsburgh, in 1801, the savvy printer and bookbinder Zadok Cramer had published the first edition of his great success, The Navigator—a mile-by-mile guide to the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Updated roughly every other year with data gleaned from letters sent east by settlers, Cramer’s book provides a portrait of the watershed in these first, not quite fully American years. “This noble and celebrated stream,” Cramer wrote of the Mississippi, “this Nile of North America, commands the wonder of the old world, while it attracts the admiration of the new.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bb/84/bb846386-fb04-4684-8b1a-beec8f9485d5/master-gmd-gmd404-g4042-g4042m-cw0047700_1.jpg)

A contemporary river traveler, accustomed to a deep and wide ribbon of water, may find it hard to envision the cluttered waterways that Cramer describes. The debris began at the Mississippi’s mouth, where shoals blocked the three forking passes that lead out into the Gulf of Mexico. Colonial pilots would unload their cargo onto smaller longboats so it could be carried 100 miles upstream to New Orleans, to avoid getting stuck in the mud. The debris continued up every tributary. Sandbars and rock bars and gravel bars could be broken down into a full taxonomy describing their size and shape and orientation: chains and traps, riffles and reefs. The largest hazards earned names all their own, which combine to make a rough American poetry. Big Bone. Pig’s Eye. Glass House. Scuffletown.

Where the rivers wound through softer soils, the banks crumbled easily. Whole trees—ancient, massive sentinels that might weigh as much as 60 tons—shed into the water, sometimes hundreds at a time. The sound, according to a later federal report, resembled “the distant roar of artillery.” Once in the channel, the roots grew matted with dirt and cobblestones and implanted in the river-bottom mud. The resulting hazards were known as snags, and they, too, inspired a full lexicon. “Planters” sat immobile. “Sawyers” bobbed in the current. “Sleepers” lay entirely beneath the water. “Wooden islands” were thick masses of driftwood that had gathered into a nearly solid whole.

All of these obstacles could be deadly. As many as a quarter of all flatboats wrecked en route to New Orleans. Among Cramer’s “instructions and precautions,” he emphasized the importance of selecting a quality vessel, especially if you hoped to make it down the whole of the Mississippi. He recommended a certain vessel in particular: a large wooden raft, typically somewhere around 60 feet by 15 feet, with a wooden box on top that served as makeshift quarters. The raft was known by many names—ark, broadhorn—but the term that stuck was Kentucky flatboat, in honor of the place where so many trips began.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/88/3d/883d8e37-062b-4742-a81b-4c3292bed4de/c7xpfd.jpg)

Some dangers could not be solved by picking the right boat: “counterfeiters, horse thieves, robbers, murderers, etc.,” as Cramer put it. So many stories were spun that it’s hard to distinguish truth from fiction. Cave-in-Rock, a riverside cavern near the mouth of the Ohio River, became a focus of blood-soaked tales. Here crews of hardened criminals were supposed

to have enticed travelers with decoys—attractive female compatriots who asked for a ride south, or a sign that advertised “Wilson’s Liquor Vault and House for Entertainment.” The victims were said to be murdered, their cargo hauled downstream for sale by the pirates. For all these tales, Cave-in-Rock was actually a regular stopping point for river travelers, something like a curiosity or tourist attraction, rather than a dangerous cavern to be avoided.

Indigenous warriors viewed the flatboats as part of an imperial invasion, enemies they needed to stop if they wanted to hold their homelands. It’s often overlooked that what Jefferson purchased in Louisiana was not the land itself, which the French had not yet fully acquired, but rather the right to negotiate for the land. With the exception of a few tracts recently acquired from the Choctaw and the Kaskaskia, the United States could not claim even the territory along the Mississippi’s east bank.

In a letter to William Henry Harrison (then the governor of the Indiana Territory) on the eve of the purchase, Jefferson had laid out his preferred strategy for getting the rest. White Americans should encircle tribal villages with settlement, he said, choking off hunting lands and thereby forcing the Indigenous people to depend on agriculture. Then the government could establish trade with Indigenous leaders and “be glad to see the good and influential individuals among them run in debt.” These measures would drive the Indigenous people to sell some land, Jefferson figured. And should anyone object and “take up the hatchet,” as Jefferson put it, the president was clear: The attackers should be crushed.

In 1804, just months after Louisiana changed hands, a group of Sauk hunters took up the hatchet: They killed three settlers along the Cuivre River, in the Ozark foothills, northwest of St. Louis. A few chiefs attended a conference with Harrison. There are no records of what transpired at the meeting, but the United States emerged with a new claim to 51 million acres of land in Illinois, Missouri and Wisconsin.

Some was not the Sauks’ to sell. One hypothesis is that the Sauk thought the treaty was a symbolic gesture, an acknowledgment that now the United States, and not Britain, would be the imperial presence looming over their lives. The text indicated that the tribe would be permitted to hunt on the land for as long as it belonged to the United States. Perhaps the Sauk did not yet realize that the U.S. government itself did not plan to keep the land. Instead, it would sell it to private citizens to build Jefferson’s empire.

Jefferson saw it as a “law of nature” that anyone who lived along the banks of a river ought to be allowed to travel its length. This was, after all, a far easier voyage than lugging crops over the mountains to Philadelphia or New York, and the flatboat rush had commenced decades before Louisiana changed hands. In the early 19th century, hundreds of flatboats traveled down the Mississippi annually, carrying the goods of a young nation: pine planks, pork, flour, whiskey and tobacco; hemp and rope and sacks; cattle and horses; cotton, animal pelts and lead; cutlery, ears of corn, and barrels of apples and potatoes and cider and dried fruit.

Theirs was a long voyage, five or six weeks of drifting atop an ever-changing river. Near Pittsburgh, the upper Ohio was transparent, revealing boulders below in its channel. Then after a few hundred miles, the terrain flattened; mud thickened the water, until it was a torrent of half-milk coffee. Even the fish in these waters seemed ungodly: Catfish could weigh 100 pounds. On some nights, they slammed against the boats so loudly that it was hard to sleep.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5c/d3/5cd3c085-a1be-476d-94dd-419906df5fc5/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_223.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/02/e5/02e51cfc-5fa1-46fa-9d3e-33e094dde3a6/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_6.jpg)

When travelers reached the Mississippi River, they faced a choice. Those interested in acquiring furs might head north, past old French villages, to reach St. Louis. Established as a trading post in 1764, the town had grown into a frontier crossroads, 200 homes perched atop the bluff where the Missouri and the Mississippi meet. The bulk of the traffic headed south, into a valley that was flat and wet—and mostly empty for the next few hundred miles. Finally, the delta plantations would appear. Those who made it safely to New Orleans sold their wares, then sold the warped wood from their flatboats as scrap. (Often the planks were laid atop the city mud to make a sidewalk.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/eb/bd/ebbdf272-962b-45d3-aaf6-aa337358febe/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_295.jpg)

The crews walked home overland, often following a set of Indigenous trails known as the Natchez Trace, traveling in packs of 20 or more to avoid being robbed. If a farmer bought anything bulky with his profits, it would have to be sent north by keelboat—a long and narrow vessel with a pointed bow and stern, which at the time was the only way to carry substantial cargo against the current. Typically 60 feet long and 8 feet wide, capable of bearing 40 tons, the keelboat was specially designed for the western rivers. Still, an upstream trip would require the muscle of at least ten men.

If a keelboat crew were lucky, they could unfurl the sails to exploit a favorable wind. Otherwise, the work was wearying. Sometimes the boat’s best swimmer would head to shore with a rope clamped in his teeth. The rope was attached to the mast, and the swimmer tied the loose end to a tree; then the crew dragged the boat forward, one thousand-foot rope length at a time. During floods and high water, keelboat crews grabbed at brush and branches along the shore so they could drag the boat forward. Typically, though, the men jammed spears into the mud at the riverbottom, and then, bracing their shoulders against a crutch at the top of the pole, crawled along the narrow planks that lined each side of the boat, beginning at the bow and working toward the stern. When a boatman reached the end of the line, he pulled his spear free, then hopped atop the cargo box at the boat’s center to sprint to the front to start again. The boatmen thus walked their way backward upriver.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ed/eb/edeb7051-c5b0-42fe-aaea-f29ca53dcfc8/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_148.jpg)

The keelboats hugged the inner bends of the river’s curves, where the water was slower, though this meant an arduous crossing after each bend ended and the next began. Often, a keelboat could manage just two crossings a day, for a total of 15 or 20 miles; afterward, their shirts bloodied, their shoulders callused, the men were rewarded with a fillee—a cup of whiskey chased by a cup of river water.

These men lived a life that was, according to one traveling preacher, “in turn extremely indolent, and extremely laborious.” The indolent moments sound pleasant enough. When the boats were moored, a fiddle was always playing. The music led to dancing and drinking—which led to cussing and fighting, in legendarily elaborate fashion. On a voyage in 1808, a traveler named Christian Schultz descended to the squalid neighborhood at the foot of the Natchez bluffs, known for its flophouses and gambling dens, and found himself captivated by a handful of boatmen caught in a dispute.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/30/b130bc4a-e616-431e-8e73-5ef3b2909756/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_23.jpg)

“I am a man; I am a horse,” one of the drunken men hollered. “I am a team. I can whip any man in all Kentucky, by God.”

The other upped the ante: “I am an alligator,” he said. “Half man, half horse; can whip any on the Mississippi by God.”

The men went at it “like two bulls,” Schultz wrote, “and continued for half an hour, when the alligator was fairly vanquished by the horse.”

The image of the boasting boatman became a literary trope, and one boatman emerged as a particular source of fascination. Mike Fink was a real man, but the stories about him are exaggerated. He’s made to sound like a hunk in a romance novel—heavily muscled, symmetrically proportioned, so frequently shirtless that his skin had darkened. He was sometimes mistaken for an Indigenous warrior. He was a crack shot and a “helliferocious fellow,” as one story put it, “and there ain’t a boatman on the river, to this day, but what strives to imitate him.” An influential account of Fink was published in 1828 by Morgan Neville, who was later deemed by one scholar to be “the first notable writer of fiction to be born west of the Alleghenies.” Neville, a Pittsburgher himself, was likely honest in his claims that he crossed paths with the legendary frontiersman.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/69/6069650b-637a-4e6a-b1e1-80c20849e06e/mike_finks_great_shot.jpg)

Neville suggests that Fink got his start as a scout in the upper Ohio River watershed, living “as did the Indian,” spending weeks alone in the woods, eating parched corn instead of bread. He slept under the stars, rolled in a blanket. Such scouts served as the advance forces for white conquest, monitoring Indigenous warriors, ready to warn nearby settlements of any hostile approach. But the scouts themselves were often the aggressors. In a telling anecdote, Neville suggests Fink shot an Indigenous hunter for the simple offense of stalking a buck that Fink hoped to kill. In 1795, after 99 chiefs signed a treaty that opened Ohio to white settlers, the scouts were out of business. By then, apparently, Fink’s lifestyle had left him unsuited to a settled home, so he committed to a life on the river. Fink served as a fitting emblem for an era—an aspirational idea for thousands of young men, some just farm boys chafing under the glare of their fathers, feeling drawn to the motion of the river.

The American claim to the watershed had a haunting backstory. Napoleon had planned to grow food along the Mississippi, which would feed the workers on his Haitian sugar plantations. The Haitian slaves revolted, successfully, from 1791 to 1804, but Napoleon had hopes of recovering the island. Once it became clear that he wouldn’t, his Louisiana farms became moot. Now, with the land in American hands, more and more enslaved laborers were arriving on the riverside farms—raising worries that they would revolt as well.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b8/be/b8be62fe-060b-4115-90cd-873993954ca0/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_182.jpg)

So when in early 1811 an army of Black and Creole men arose along the Mississippi River, 30 miles upstream of New Orleans, white Americans saw this as a nightmare coming true. Armed with machetes and pitchforks, these fighters seized a cache of muskets, then burned down a mansion. They had likely gathered in the swamps behind the plantation to plan this attack. The rebels waved banners and marched to a drumbeat, sacking plantations as they descended on the city, recruiting more soldiers at every stop. In their wake, they created a zone, 30 miles long, where emancipation became, if not the law, then the fact on the ground.

The response was swift and strong: Within a few days, the U.S. Army, working in concert with a local militia, routed the uprising. One participant called it “une grande carnage.” The severed heads of rebels were placed atop pikes along River Road, a reminder, to anyone else contemplating freedom, about who was in charge.

Even before the War of 1812 began, conflict was well underway in the increasingly dense settlements along the Ohio River. Many Indigenous people, subscribing to the theory that the enemy of my enemy is my friend, had allied with the British crown. Two Shawnee brothers set up the headquarters for a burgeoning anti-American movement in the unconquered territory along the Wabash River. Late in 1811 a frontier militia led by William Henry Harrison burned the village.

The next year, when Congress made this a proper war, the legendary Sauk warrior Black Hawk knew which side to join. Along with a battalion of Sauk and Winnebago soldiers, he took part in a British attack on a small American fort. Two years later, when the U.S. Army sent a fleet upstream with plans to demolish the great Sauk village, a group of 1,000 warriors drove back the boats. To the west, traders were reporting that the rivers throughout the Missouri Valley were “shut against” the Americans, too. Despite the Louisiana Purchase, then, the watershed could hardly be called American land.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e8/17/e817cd5b-a83f-4e56-908a-b7de7090fc11/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_28.jpg)

In January 1815, the British decided to seize New Orleans. The U.S. forces were led by a lean and angry soldier named Andrew Jackson, who upon his death in 1845 was heralded in one eulogy as the embodiment of “the true spirit of his nation.” Technically, that spirit had been forged east of the mountains, where Jackson’s father, an immigrant from Ireland, had worked himself to death trying to eke a living out of a Carolina farm. After his family’s home was captured during the Revolution, 14-year-old Jackson refused to polish a British officer’s shoes. This act of resistance earned him a sword-slashed scar on his head and hand. Thereafter, it seems, any slight toward Jackson sparked furious indignation.

Jackson went on to join the river trade, where he carted swan skins, feathers, pork and beef—and notably, enslaved humans—as far south as Natchez. Eventually he established a business empire in Nashville, along the Cumberland River, that included a tavern, a racetrack and, since some of his customers paid in bartered goods, a trading depot to carry the wares downstream to market. He entered politics, too, and in 1812 was prominent enough to be put in charge of the local militia. He declared to his troops that their greatest duty as westerners would be to defend their mother river against invasion. Three years later, with that invasion imminent, he marched his volunteers into New Orleans.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/d8/56d8b3cb-d3d5-40d7-b367-e01e2b32eda8/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_70.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/75/3375666a-5a67-4725-a006-e0a9146780ca/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_48.jpg)

Jackson’s men were mostly the hardscrabble sort who’d established farms along the western rivers—the flatboaters, in other words. In New Orleans, they were joined by French-descended pirates, Choctaw warriors and free men of color. This motley assembly—“perhaps the most racially varied ‘American’ military force ever,” according to scholar Thomas Ruys Smith—routed the royal army. The Brits were perhaps too well trained: As they streamed across a fallow field of sugarcane just downstream of the city, they refused to abandon their orderly lines—even as they were met by a constant barrage of musket fire. A quarter of the 8,000 British soldiers suffered casualties, compared with fewer than 100 on the American side.

For the Americans, the Battle of New Orleans was a triumph after years of chaos and loss—enough of a triumph, apparently, to finally settle the issue of who owned the river at the continent’s heart. The massive British death toll was extolled in newspaper poetry, and within a few years the date of the battle, January 8, was named an American holiday. When Andrew Jackson ran for president, 13 years after his victory, he chose as a campaign song an old ballad that celebrated the battle.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b3/b6/b3b6fd9e-9289-4e50-ac28-78edda755215/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_106.jpg)

By then, the British had abandoned their Indigenous allies, which helped ensure that the length of the river was in secure American control. The U.S. Army sent a force north, to build a fort at Rock Island, Illinois, and it sent Prospect Robbins and Joseph Brown west, on their trek through the Arkansas swamps. The imagined grid of the empire for liberty was, chain by chain, laid atop the land.

Adapted from The Great River: The Making and Unmaking of the Mississippi by Boyce Upholt. Copyright © 2024 by Boyce Upholt. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Correction, July 24, 2024: An earlier version of this piece misstated the mechanics of propelling a flatboat upstream. It has been updated to make clear that boatmen walked the plank from bow to stern.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1750x1167:1751x1168)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fd/32/fd322597-dd6d-4c89-b35b-85f88826ddd3/202404louisiana_purchase_mississippi_river_255.jpg)