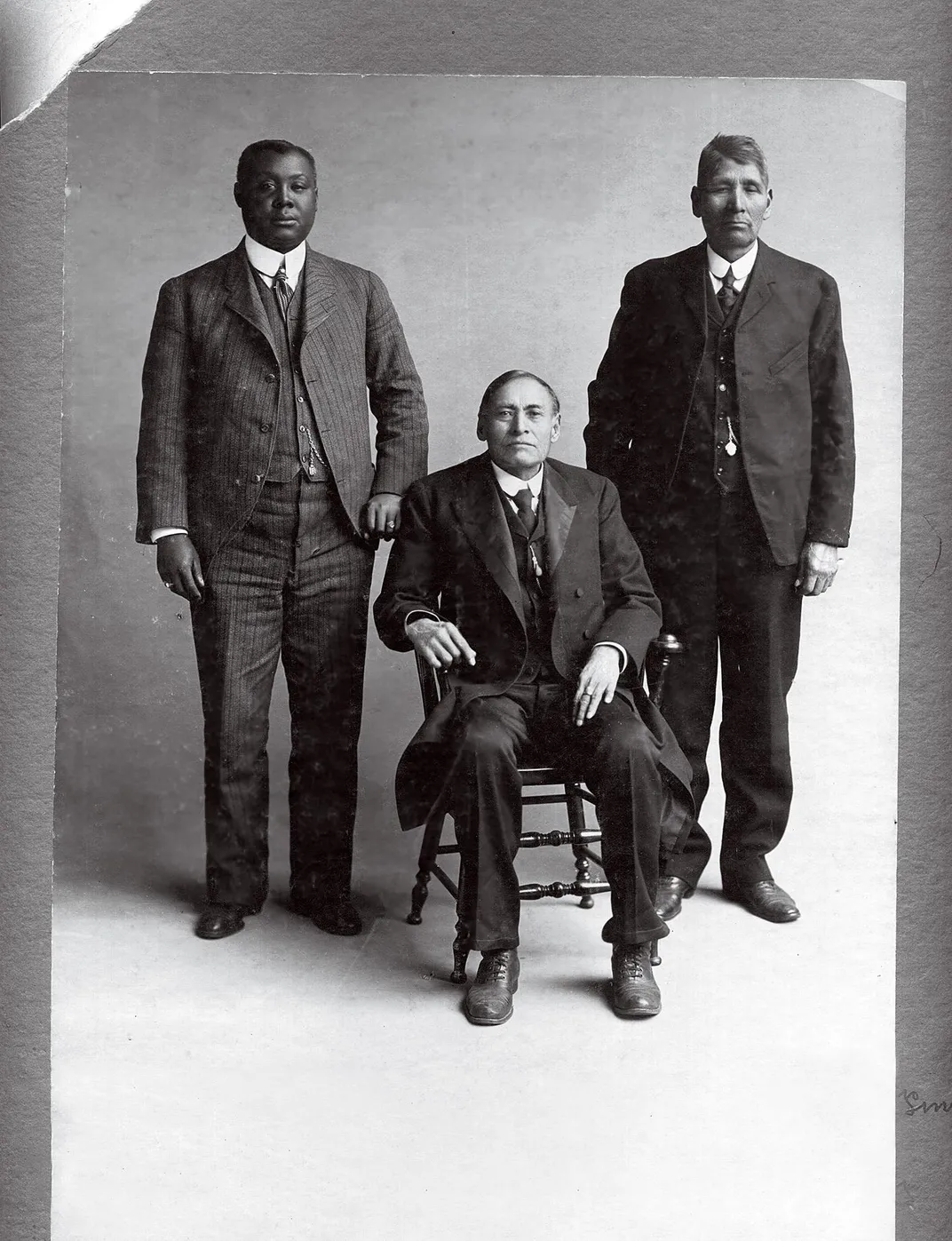

In October 1907, eleven black leaders from the “Twin Territories,” out on the frontier, traveled to Washington, D.C. in a last-ditch effort to prevent Oklahoma from becoming a state. Among them were A.G.W. Sango, a prominent real estate investor who wanted to draw more black people out West; W.H. Twine, a newspaper editor whose weekly Muskogee Cimeter had been mounting a forceful opposition campaign against statehood for weeks; and J. Coody Johnson, a lawyer who was a member of the Creek Nation and had served in its legislature in the town of Okmulgee. These men had carved unlikely paths to success on the outskirts of America, where the nation’s racial hierarchy had not yet fully calcified. But they feared that when Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory were combined to form a new state, Jim Crow laws would again thrust black people under the heel of white supremacy. The men needed help to prevent that from happening.

They hoped to find an ally in President Theodore Roosevelt. He was a member of their own Republican Party and had signaled that he would veto any state constitution that included Jim Crow discrimination. Over the course of a few days, the delegation met with the U.S. attorney general, the secretary of the interior, and finally, the president himself. Details of the exchange are unknown, but the group must have told Roosevelt how Oklahoma legislators planned to institutionalize segregation, including banning black people from white train cars, keeping them out of white schools and preventing them from voting. Some of the white residents of the territories wanted to do worse.

(As part of our centennial coverage of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, read about efforts to recover the massacre's long-buried history in "American Terror")

These black men had no say in drafting the state constitution, and they didn’t have the numbers to vote it down at the ballot box. But they thought Roosevelt might recognize that Oklahoma did not deserve to become a warped appendage of the Deep South, when it could be so much more—when it had been so much more. The delegation left Washington feeling optimistic. “The work has been done,” Twine reported in the Cimeter, “and eagerly are results awaited.”

* * *

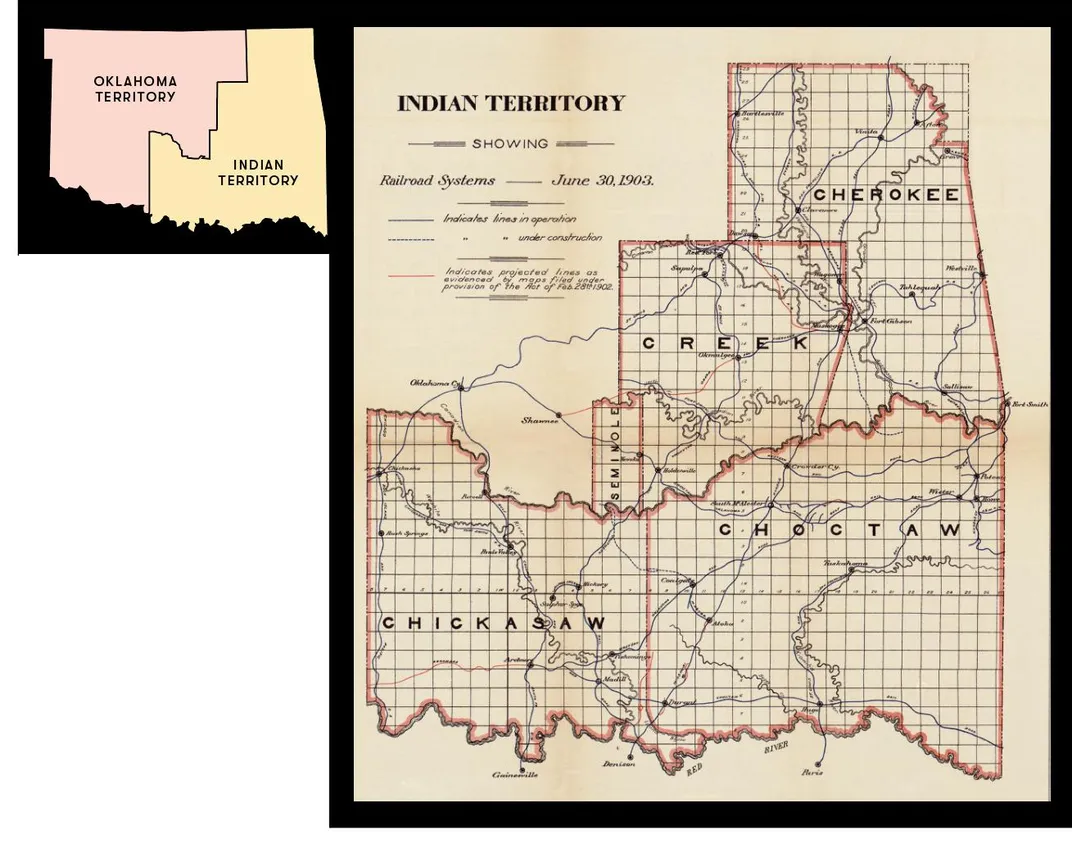

Black people arrived in Oklahoma long before the prospect of statehood. The first to settle in the area were enslaved by Native American tribes in the Deep South, and they made the journey in the 1830s as hunters, nurses and cooks during the brutal forced exodus known as the Trail of Tears. In Indian Territory (much of today’s eastern Oklahoma) slavery as practiced by the Creek, Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw and Seminole tribes sometimes resembled the vicious plantation systems of the South. During the Civil War, the Five Tribes sided with the Confederacy, but after the war most of the tribes, bound by new treaties with the federal government, granted formerly enslaved people citizenship, autonomy and a level of respect unheard of in the post-Reconstruction South. In the Creek and Seminole tribes, black tribal members farmed alongside Native Americans on communally owned land, served as justices in tribal governments, and acted as interpreters for tribal leaders in negotiations with the growing American empire.

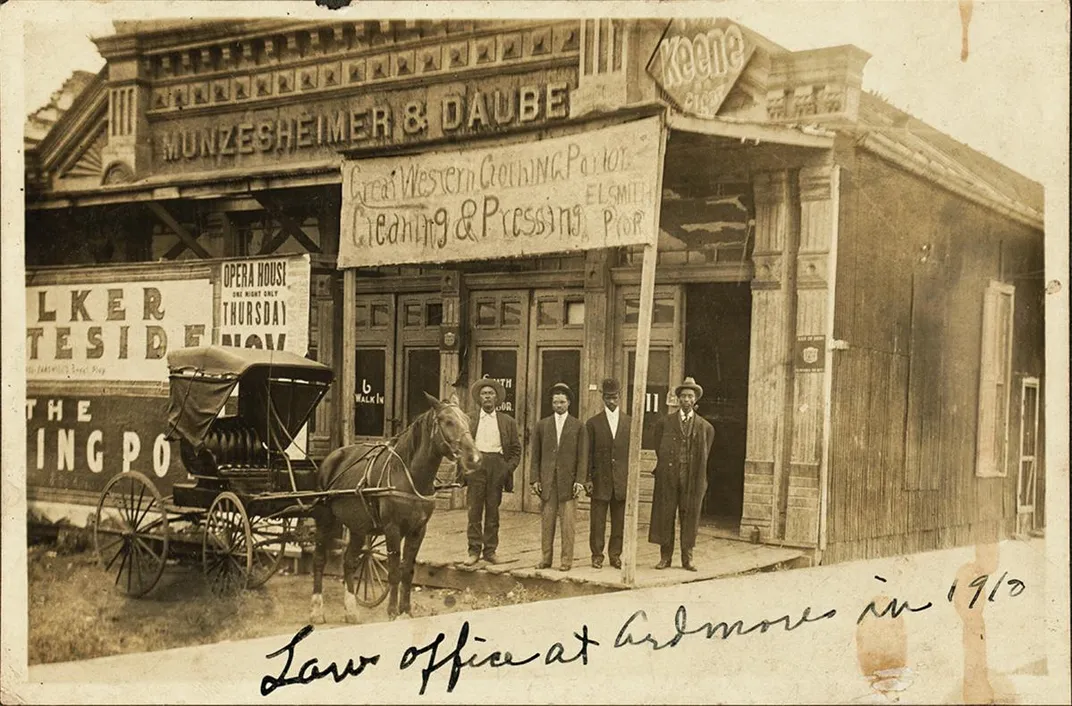

Black Americans with no ties to the Five Tribes journeyed to Oklahoma on their own accord, attracted by the promise of equality on the frontier. Edward McCabe, a lawyer and politician from New York, ventured to Oklahoma Territory in 1890, where he founded a town exclusively for black settlers called Langston, promising his brethren in the South a utopia where “the colored man has the same protection as his white brother.” Ida B. Wells, the crusading journalist who dedicated her life to chronicling the scourge of lynching, visited Oklahoma in April 1892 and saw “the chance [black people] had of developing manhood and womanhood in this new territory.” There was truth to these proclamations. In pre-statehood Oklahoma, it was common for white and black children to attend the same schools as late as 1900. Black politicians held public office not only in tribal governments but also in Oklahoma Territory, the modern-day western half of the state. In the early days of Tulsa, black residents owned businesses in the predominantly white downtown district and even had white employees.

Oklahoma was evolving into an unusually egalitarian place. But it was also nurturing a vision at odds with America’s increasingly rapacious capitalist ideals. In 1893, former Massachusetts senator Henry Dawes led a federal commission to compel the Five Tribes to divide their communally owned lands into individually owned allotments. Dawes considered himself a “friend of the Indians,” as white humanitarians of the era were called. But his approach to “helping” Native Americans hinged on their assimilation into white America’s cultural and economic systems. He was mystified by Native Americans’ practice of sharing resources without trying to exploit them for personal profit. “There is no selfishness, which is at the bottom of civilization,” he reported to the Board of Indian Commissioners in Washington. “Until this people consent to give up their lands...they will not make much progress.” In a series of forced negotiations beginning in 1897, Congress compelled the Five Tribes to convert more than 15 million acres of land to individual ownership. Tribal members became U.S. citizens by government mandate.

Black tribal members, who were classified as “freedmen” by the Dawes Commission, initially seemed to benefit from the allotment process. They were granted approximately two million acres of property, the largest transfer of land wealth to black people in the history of the United States. It was the “40-acres-and-a-mule” promise from the Civil War made real; black members of the Creek Nation actually got 160 acres. But the privatization of land also made tribal members vulnerable to the predations of the free market. Though Congress initially restricted the sale of land allotments, in order to prevent con men from tricking tribal members out of their property, these regulations disappeared under pressure from land developers and railroad companies. Eventually, many Native Americans were swindled out of their land; black people lost their protection first. “It will make a class of citizens here who, because of the fact that they do not understand the value of their lands, will part with them for a nominal sum,” J. Coody Johnson warned at a congressional hearing in Muskogee in 1906. Officials ignored him.

Graft and exploitation became widespread practices in Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory. Given implicit permission by the federal government, white professionals continued a wide-ranging effort to dismantle black wealth in the region. Black children allotted land bubbling with oil were assigned white legal guardians, who sometimes stole tens of thousands of dollars from their wards. Real estate men tricked illiterate black people into signing predatory contracts, sometimes for under $1 per acre (less than one-sixth their average value, according to the congressional treaties). Black-owned property was often simply taken by force. White locals ran black residents out of communities like Norman, the current home of the University of Oklahoma, and established “sundown towns,” where no black person was welcome at night. None of this was done in secrecy; it was spoken of casually, boastfully, even patriotically. “We did the country a service,” C.M. Bradley, a Muskogee banker who was arrested for defrauding black landowners, told a congressional panel. “If this business that I am in is a grafting game, then there is not a business in the world that is not a graft.”

Black communities in the Twin Territories also wrestled with deep internal tensions. At first, black tribal members clashed with the African Americans who immigrated later. The freedmen viewed the black interlopers as participants in the white man’s plunder and called them “state Negroes” (or sometimes a Creek word for “white man’s Negro”). The new black migrants called the black tribal members “natives.” In Boley, an all-black town populated by migrants, freedmen would gallop through the streets at night shooting out residents’ windows. In the pages of the black press, businessmen admonished freedmen for betraying the race by selling their land allotments to white men instead of black entrepreneurs. Black migrants and freedmen, in other words, did not see themselves as sharing a racial identity.

The people around them, though, increasingly did. Within the Five Tribes, earlier notions of egalitarianism were replaced with a fixation on blood quantum—a person’s percentage of “Indian blood” based on their ancestry—as a marker of tribal legitimacy. (Creek descendants of slaves are still fighting today for their tribal citizenship to be acknowledged in both tribal and U.S. courts.) Meanwhile, as Jim Crow crept westward across the prairies, new laws excluded blacks from white schools. Black political aspirations dimmed as many Republicans began advocating Jim Crow policies in an effort to secure white votes. Sundown towns spread. Lynchings of black people became more common. “We are vilified and abused by the Guthrie lily-whites until election time draws near and then the crack of the whip is heard,” a black Republican named C.H. Tandy said during this period. “I have talked to all my brethren and they are mad. We won’t stand it any longer.”

The battle over Oklahoma’s constitution represented a bellwether for how legally sanctioned racism would be tolerated in the United States at the dawn of a new century. Since the 1890s, settlers in the Twin Territories had advocated statehood to legitimize their encroachment on land that wasn’t theirs. As the white population of the region grew, the political power of competing groups waned. In 1905, Congress ignored an effort by the Five Tribes to get Indian Territory accepted into the Union as a state on its own, governed by Native Americans. The next year, when white leaders assembled a constitutional convention with congressional approval, black people were largely shut out of the drafting of the document. Statehood would cement white political power as the land allotment process had guaranteed white economic power.

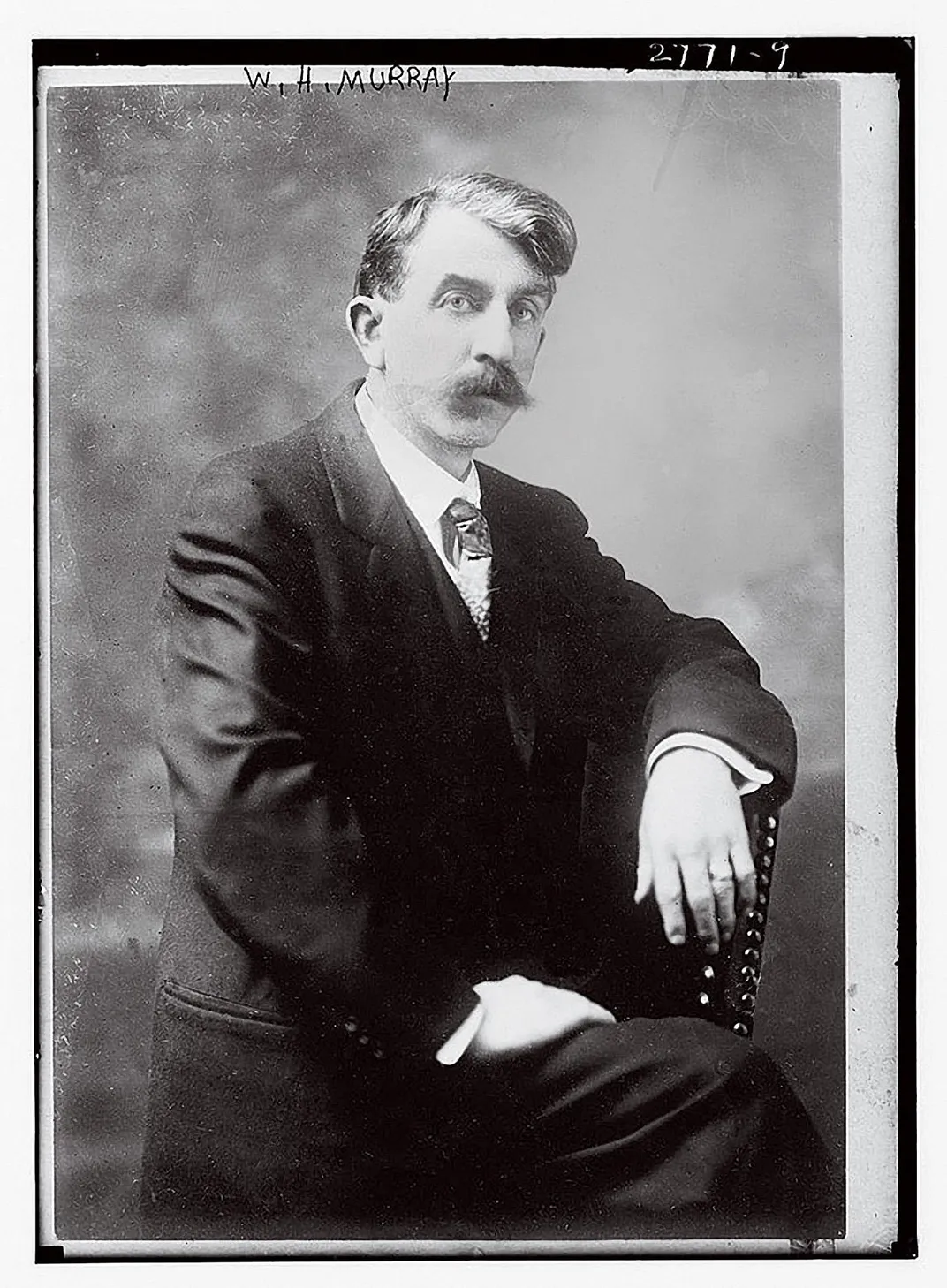

William H. Murray, the Democratic delegate who was elected president of the constitutional convention, summed up the racial philosophy of the Twin Territories’ white leaders in his inaugural convention speech: “As a rule [Negroes] are failures as lawyers, doctors, and in other professions...He must be taught in the line of his own sphere, as porters, bootblacks, and barbers and many lines of agriculture, horticulture and mechanics in which he is an adept, but it is an entirely false notion that the negro can rise to the equal of a white man.”

Murray called for separate schools, separate train cars and a ban on interracial marriage. The convention hall itself had a segregated gallery for black onlookers. But black leaders refused to cede their civil rights. While the mostly white convention was happening in Guthrie, in December 1906, black residents organized a competing convention in Muskogee. They declared the constitution “a disgrace to our western civilization . . . that would cause endless strife, racial discord, tumult and race disturbances.” In April 1907, three hundred African Americans, including J. Coody Johnson, met at the Oklahoma City courthouse to convene the Negro Protective League, a black advocacy group. They galvanized opposition to the constitution in every town and hamlet, organizing petitions and mailing out thousands of letters to black citizens directing them to vote against its ratification. “Help us defeat a constitution that lays the foundation for the disfranchisement of our people in the new state and...measures calculated to humiliate and degrade the whole race,” black residents demanded in a petition to state Republican leaders. It failed.

In September 1907, the constitution was put to a public vote, and passed with 71 percent approval. This is what led the delegation of black leaders to travel to the nation’s capital the following month. They hoped President Roosevelt would block the state’s admission to the Union because of the self-evident racism of its proposed government. The conditions for accepting Oklahoma into the Union were already clear: In the 1906 federal law allowing for Oklahoma’s statehood, Congress required the new state’s constitution to “make no distinction in civil or political rights on account of race or color.” But Murray and other convention delegates were careful to leave out certain egregious discriminatory provisions. They understood how to follow the letter of the law while trampling over the spirit of it.

* * *

By the time the black leaders were standing face to face with Roosevelt, he had apparently already made up his mind.

On November 16, 1907, the president signed the proclamation turning Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory into the 46th U.S. state, Oklahoma. Despite Roosevelt’s professed misgivings about admitting a state that discriminated against a portion of its citizens, the constitution itself enshrined the segregation of schools. With the president’s signature secured, state leaders moved aggressively to enact the rest of their Jim Crow agenda. The very first law passed by the state legislature segregated train cars. Next, the legislature passed the so-called “grandfather clause,” which circumvented federal voter rights protections by instituting a literacy test on any person whose ancestors had not been allowed to vote before 1866. Naturally, that included all descendants of slaves. Ultimately, the legislature would segregate nearly every aspect of public life—hospitals, cemeteries, even phone booths. Oklahoma’s formal and fully legalized racism was actually more rigid than that in much of the Deep South, where Jim Crow was sometimes upheld by custom and violence rather than legal mandate. In the South, segregation emerged from the vestiges of slavery and failed Reconstruction; in Oklahoma, it was erected statute by statute.

Ironically, at the time, Oklahoma’s state constitution was hailed as a victory for the progressive movement. William Murray, the constitutional convention president and future Oklahoma governor, earned the folksy nickname “Alfalfa Bill,” and was seen as an anti-corporate crusader in an age of oppressive monopolies. The constitution allowed for municipal ownership of utilities, increased taxes on corporations, made many more public offices subject to democratic elections, and set train fares at the affordable rate of 2 cents per mile. The progressive magazine the Nation declared that Oklahoma’s constitution had come “nearer than any other document in existence to expressing the ideas and aspirations of the day.”

But this view of “progress” measured success only by how much it benefited white people. And it led to broader disenfranchisement when those in charge perceived threats to their power. An early push at the convention to expand suffrage to women, for example, failed when delegates realized that black women were likely to vote in larger numbers than white ones.

And the constitution had another profound consequence that would alter the demographic landscape of the new state. It erased the line between “freedmen” and “state Negroes” once and for all. The document stipulated that laws governing “colored” people would apply only to those of African descent. “The term ‘white race,’ shall include all other persons,” it stated. In other words, segregation measures would apply to black migrants and black tribal members, but not to Native Americans.

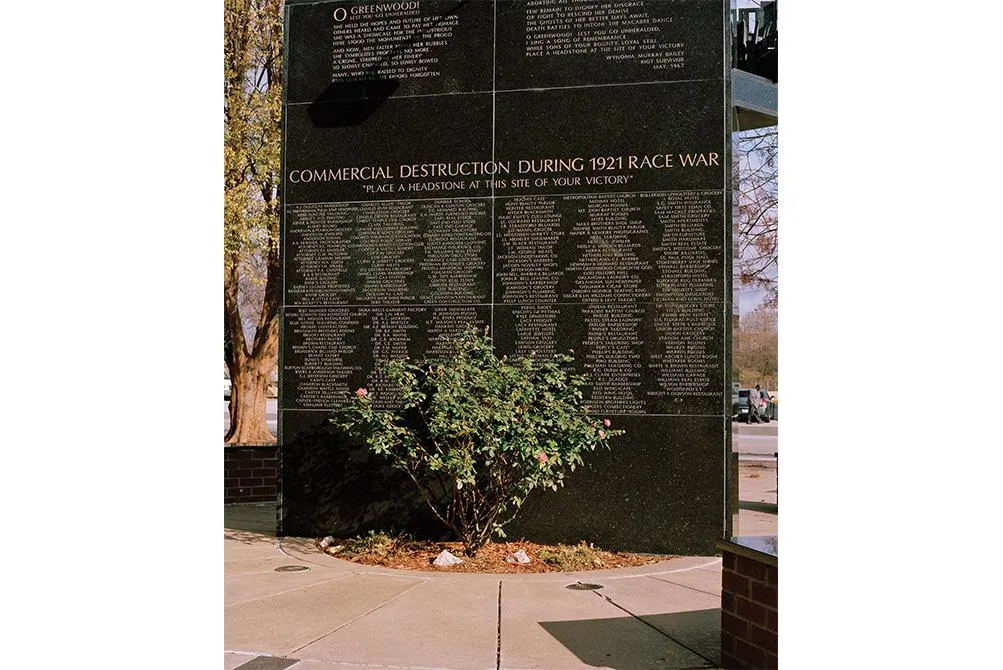

With all black people in Oklahoma now grouped together, a new and more unified black identity began to emerge. It was represented most vividly in a neighborhood on the northern edge of Tulsa, in what had been Indian Territory, where black people learned to be collaborative, prosperous and defiant. The place was called Greenwood.

* * *

O.W. and Emma Gurley arrived in Tulsa from Perry, Oklahoma Territory, in 1905, on the eve of a radical transformation. The city, which occupied land long owned by the Creek Nation, had recently been incorporated by white developers in spite of opposition by Creek leaders. White newcomers were rapidly expanding neighborhoods south of the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway. The Gurleys decided to settle north, and opened the People’s Grocery Store on a patch of low-lying undeveloped land. Just a few months after their store opened—“The Up-to-Date Grocer for the Choicest Meats, Groceries, Country Produce”—a geyser of oil erupted into the sky just south of Tulsa. The discovery of the massive reservoir, which came to be known as the Glenn Pool, transformed the tiny frontier outpost into one of the fastest-growing locales in the United States. Boosters called it the “Oil Capital of the World” and “The Magic City.”

Oil, however, played a secondary role in the black community’s success. Black laborers were systematically excluded from participating directly in the oil boom; in 1920, there were nearly 20,000 white oil well workers, compared with only about 100 black ones. But black laborers and residents did benefit from the wealth that transformed Tulsa, becoming cooks, porters and domestic servants.

And from the seed of People’s Grocery Store an entrepreneurial class took root on Greenwood Avenue. Robert E. Johnson ran a pawnshop and shoe store. James Cherry was a plumber, and later, the owner of a popular billiards hall. William Madden mended suits and dresses in the tailor shop he set up in his own home. An African American Episcopal church sprouted up just north of these businesses, and a Baptist church was opened just east. Homes fanned out around all the enterprises.

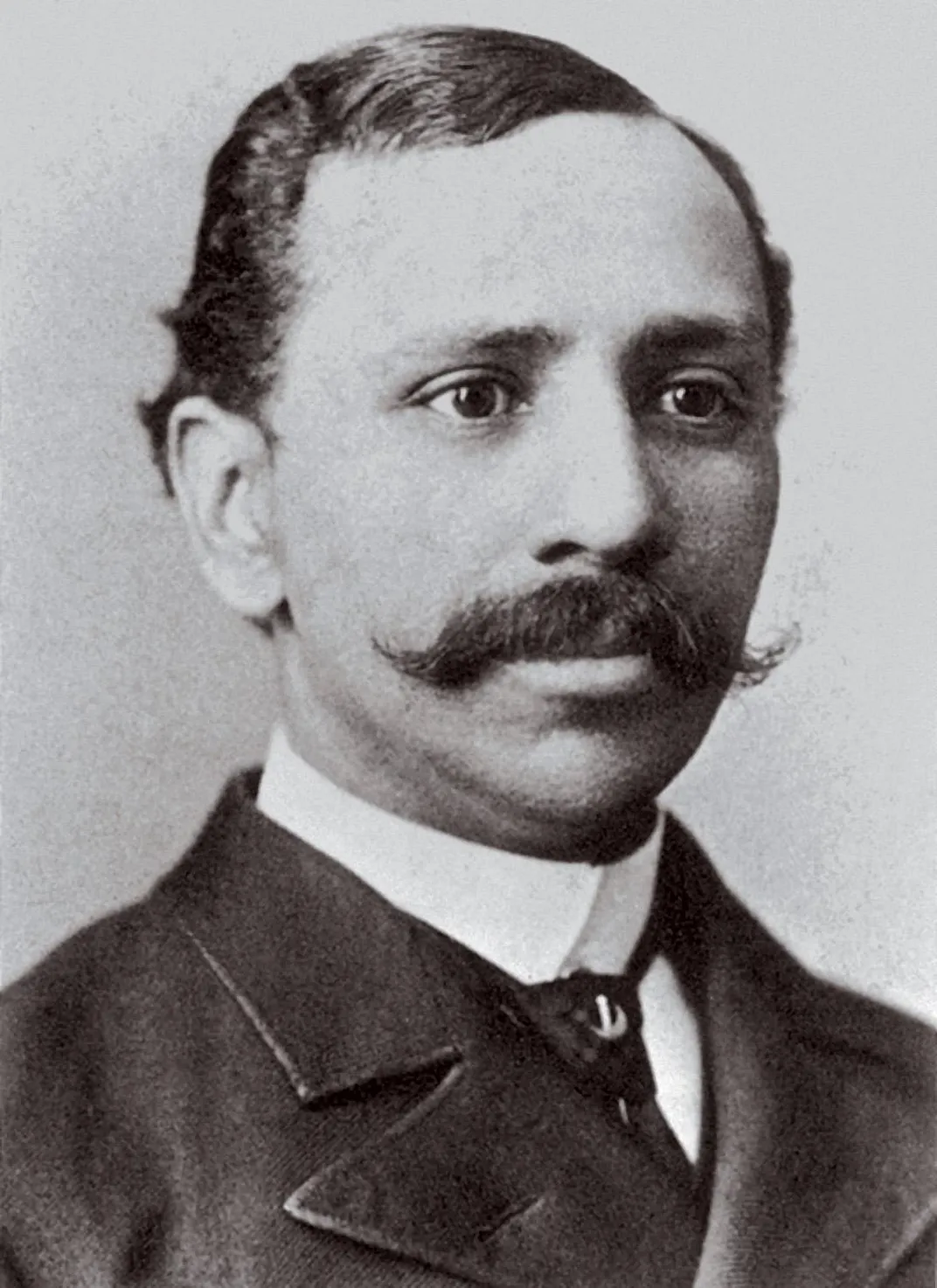

Among the most prominent early entrepreneurs was J.B. Stradford, a “state Negro” from Kentucky who had arrived in Tulsa before statehood. As a real estate agent, Stradford helped nurture the nascent neighborhood into a thriving black enclave filled with regal hotels, lively theaters and elegant clothing stores. He held a deep-seated belief that black people would find the most success working independently of white people and pooling their resources. “We find among the white people that they are not only prosperous individually but also collectively,” he said in a 1914 address to Greenwood entrepreneurs. “The white man has put his money together for the purpose of employing, elevating, and giving to those who are deserving a chance to arrive at prominence in the race of opportunities.”

Greenwood’s leaders saw their fight for basic civil rights and economic prosperity as deeply linked. They married Booker T. Washington’s calls for economic uplift with W.E.B. Du Bois’ demands for social equality. “I came not to Tulsa as many came, lured by the dream of making money and bettering myself in the financial world,” wrote Mary E. Jones Parrish, a stenographer and journalist from Rochester, New York. “But because of the wonderful co-operation I observed among our people.”

For Greenwood’s many accomplished businesswomen, political activism, community building and an entrepreneurial spirit were intertwined. Loula Williams’ Dreamland Theater hosted vaudeville acts and boxing bouts, but it also served as a headquarters for community leaders who worked to challenge the legal encroachments of Jim Crow. Carlie Goodwin managed a slate of real estate properties along with her husband, J.H.; she also led a protest at the local high school when teachers tried to exploit black students’ labor by having them wash white people’s clothes. Mabel Little, a hairdresser who worked as a sales agent for Madam C.J. Walker, the black cosmetics titan, owned her own salon on Greenwood Avenue and started a professional organization for local beauticians.

Black tribal members also played a crucial role in Greenwood. B.C. Franklin, a member of the Choctaw tribe, opened a law practice that would help protect black property rights after the violent white-led massacre that destroyed much of the neighborhood in 1921. (Franklin’s son, John Hope Franklin, became the distinguished scholar of African American history; his grandson, John W. Franklin, was a longtime senior staff member at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.) Wealthy tribal members who had oil-producing wells on their allotments injected money back into the community. A.J. Smitherman, the fiery editor of the Tulsa Star, was not a freedman himself, but he formed a protective league meant to stop unscrupulous white lawyers from gaining guardianship over freedmen children.

But Oklahoma’s white establishment stymied every effort by the state’s black citizens to improve their station. Stradford filed a lawsuit against the Midland Valley Railroad after being forced to sit in a Jim Crow car; he lost the case in the Oklahoma Supreme Court. Hundreds of black Tulsans fought a local ordinance that prevented them from moving onto any block that was mostly white. The measure remained on the books. The two white-owned newspapers, the Tulsa Tribune and the Tulsa World, reported every crime they could uncover in the neighborhood they sometimes called “N-----town,” and ignored most black success stories.

And then there was the violence. Black people had been navigating white violence for centuries, but World War I marked a change in how African Americans viewed their own citizenship. After thousands of black soldiers were shipped overseas to fight for their country and experienced life outside Jim Crow, black writers and activists began to call for resistance against white incursions at home. In 1919, during a bloody period that came to be called the “Red Summer,” race riots erupted in more than 30 American cities, from Omaha, Nebraska, to Washington, D.C. In Elaine, Arkansas, a few hundred miles from Tulsa, an estimated 200 black people were killed by white vigilantes who falsely believed that black sharecroppers were staging a violent uprising.

Greenwood residents learned about such violence with growing trepidation, yet the neighborhood was thriving. By 1920, J.B. Stradford had opened his Stradford Hotel, a three-story, 68-room structure, at the time the largest black-owned and operated hotel in the country. The Dreamland Theater was on its way to becoming an empire, expanding to include venues in Muskogee and Okmulgee. Greenwood boasted a hospital, two theaters, a public library, at least a dozen churches, three fraternal lodges, and a rotating cast of restaurants, hairdressers and corner dives, serving about 11,000 people.

On May 30, 1920, a year and a day before Greenwood began to burn, a man named LeRoy Bundy went to speak at the First Baptist Church, just off Greenwood Avenue. Three years earlier, Bundy had survived a riot in East St. Louis, Illinois, and had served time in prison afterward for supposedly orchestrating an attack on police officers. He appealed and the verdict was overturned. Bundy came to talk about his experiences as a witness to the destruction. Forty-eight people had been killed, more than 240 buildings destroyed. It would have been difficult for Greenwood’s residents, half a century removed from the Civil War, to imagine urban destruction in America on a larger scale.

In retrospect Bundy’s visit appears as a warning. Three months later, two men were lynched in Oklahoma in a single weekend: a white man named Roy Belton in Tulsa, and a black man named Claude Chandler in Oklahoma City. Tulsa County Sheriff James Woolley called the mob attack under his watch “more beneficial than a death sentence pronounced by the courts.” The Tulsa World called the lynching a “righteous protest.” Only A.J. Smitherman and his Tulsa Star seemed to intuit how calamitous the collapse of the rule of law would be for black people. “There is no crime, however atrocious, that justifies mob violence,” he wrote in a letter to Oklahoma Gov. James B.A. Robertson.

Smitherman was a staunch advocate for a muscular form of black self-defense. He chastised black residents in Oklahoma City for failing to take up arms to protect Claude Chandler. But, like the men who had ventured to Washington, D.C. to lobby President Roosevelt 13 years earlier, he believed that black people’s best hope for safety and success came in forcing the country to live up to its own stated promises. Smitherman and the other Greenwood residents bore the burden of living in two Americas at once: the idealized land of freedom and opportunity and also a land of brutal discrimination and violent suppression.

Smitherman’s very name—Andrew Jackson—carried the weight of the contradiction. It was President Jackson who first banished Native American tribes and the black people they enslaved to Oklahoma in service to the interests of white settlers. But Smitherman could articulate better than most what it meant to be a patriot living outside the prescribed boundaries of patriotism: “[The American Negro] is not a real part and parcel of the great American family,” he wrote. “Like a bastard child he is cast off, he is subjected to injustice and insult, he is given only the menial tasks to perform. He is not wanted but is needed. He is both used and abused. He is in the land of the free but is not free. He is despised and rejected [by] his brothers in white. But he is an American nevertheless.”

Greenwood’s residents, deprived of justice long before their neighborhood was burned to the ground, continuously called for their city and their country to honor its ideals and its plainly written laws. That demand resounded before the events of 1921, and it continues to echo long afterward.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/af/3d/af3d4e30-e10a-46bf-8250-31427855dcc2/ok_history_v2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/0a/ee0a962b-9153-4fbf-9999-f18d07f387a8/opener_history_v2.jpg)