The Unsolved Murder of Civil Rights Activist Harry Moore

An organizer who campaigned for justice in 1940s Florida, Moore was among the first martyrs to the cause

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/d7/0ed7ff66-d5ab-4e97-907e-0d6011022bb7/moorehome_mcc.jpg)

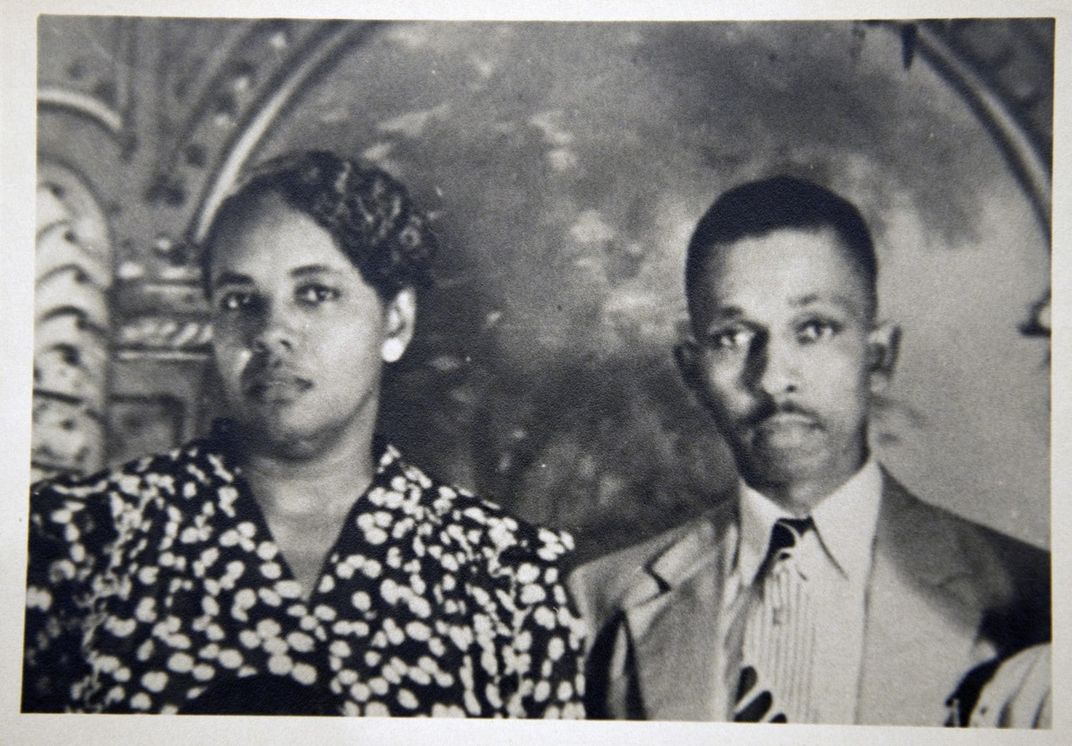

It was late on Christmas night, 1951, but Harry and Harriette Moore had yet to open any gifts. Instead they had delayed the festivities in anticipation of the arrival of their younger daughter, Evangeline, who was taking a train home from Washington, D.C. to celebrate along with her sister and grandmother. The Moores had another cause for celebration: the day marked their 25th wedding anniversary, a testament to their unshakeable partnership. But that night in their quiet home on a citrus grove in rural Mims, Florida, the African American couple were fatal victims of a horrific terrorist attack at the hands of those who wanted to silence the Moores.

At 10:20 p.m., a blast ripped apart their bedroom, splintering the floorboards, ceiling and front porch. The explosion was so powerful that witness reported hearing it several miles away. Pamphlets pushing for voters’ rights floated out of the house and onto the street, remnants of a long fight for justice. Harry Moore had spent much of the last two decades earning the enmity of Florida’s white supremacists as he organized for equal pay, voter registration, and justice for murdered African Americans. And yet despite his immense sacrifice and the nation’s initial shock at his assassination, Moore’s name soon faded from the pantheon of Civil Rights martyrs.

After the attack, Moore’s mother and daughter knew they would be unable to get an ambulance willing to transport a black victim, so nearby relatives drove the wounded Harry and Harriette to the town of Sanford, which was more than 30 miles away on a dark, two-lane road bracketed by dense foliage. Harry died shortly after arriving in the hospital, Harriette would die a little more than a week later. When Evangeline arrived at the train station the next day, “She didn’t see her mother and father, but she saw her aunts and uncles and family members. She knew something was wrong,” says Sonya Mallard, coordinator for the Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Cultural Complex, who knew Evangeline before her death in 2015. Her uncle broke the news on the drive to the hospital, and “her world was never the same again. Never.”

In the years before his death, Harry Moore was increasingly a marked man—and he knew it. But he had begun charting this course in the 1930s, when he worked tirelessly to register black voters. He later expanded his efforts into fighting injustice in lynching cases (Florida had more lynchings per capita than any other state at the time), putting him in the crosshairs of Florida’s most violent and virulent racists.

“Harry T. Moore understood that we had to make a better way, we had to change what was going on here in the state of Florida,” says Mallard. Traveling around the state on roads where it was too dangerous to even use a public restroom, Moore’s mother, Rosa, worried he’d be killed, “but he kept on going because he knew it was bigger than him,” says Mallard.

Moore was born in 1905 in the panhandle town of Houston, Florida. His father, Johnny, owned a small shop and worked for the railroad, and died when Harry was just 9 years old. After trying to support her son as a single parent, Rosa sent Harry to live with his aunts in Jacksonville, a hub for African American business and culture that would prove to be influential on the young Moore. After graduating from Florida Memorial College, as today’s university was then known, Moore likely could have made a relatively comfortable life in Jacksonville.

However, the climate in Florida as a whole as hostile to African Americans. His formative years were ones of pervasive racial violence often unchecked by officials. Before the 1920 election, displaying the impunity enjoyed by white supremacists, the Ku Klux Klan “marched in downtown Orlando specifically to intimidate black voters,” says Ben Brotemarkle, executive director of the Florida Historical Society. When a man named July Perry came to Orlando from nearby Ocoee to vote, he was beaten, shot and hung from a light post and then the primarily African American town was burned in a mob rampage that killed dozens. For decades after, Ocoee had no black residents and was known as a “sundown town”; today the city of 46,000 is 21 percent African American.

In 1925, Moore began teaching at a school for black students in Cocoa, Florida, a few miles south of Mims and later assumed the role of principal at the Titusville Colored School. His first year in Cocoa, Harry met Harriette Simms, three years his senior, at a party. She later became a teacher after the birth of their first daughter, Annie Rosalea, known as Peaches. Evangeline was born in 1930.)

His civic activism flowed from his educational activism. “He would bring his own materials and educate students about black history, but what he also did was bring in ballots and he taught his students how to vote. He taught his students the importance of the candidates and making a decision to vote for people who took your interests seriously,” says Brotemarkle.

In 1934, Moore joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), an indication of his growing interest in civic matters. In 1937, Moore pushed for a lawsuit challenging the chasm between black and white teachers’ salaries in his local Brevard County, with fellow educator John Gilbert as the plaintiff. Moore enlisted the support of NAACP lawyer (and later Supreme Court Justice) Thurgood Marshall, the start of their professional collaboration. The lawsuit was defeated in both the Circuit Court and the Florida Supreme Court. For his efforts, the Moores later lost their teachings jobs—as did Gilbert.

In the early 1940s, Moore organized the Florida State conference of the NAACP and significantly increased membership (he would later become its first paid executive secretary). He also formed the Progressive Voters’ League in Florida in 1944. “He understood the significance of the power of the vote. He understood the significance of the power of the pen. And he wrote letters and typed letters to anyone and everyone that would listen. And he knew that [African Americans] had to have a voice and we had to have it by voting,” says Mallard. In 1947, building on the U.S. Supreme Court case in which Marshall successfully argued against Texas’ “white primary” that excluded minority voters, Moore organized a letter writing campaign to help rebuff bills proposed in the Florida legislature that would effectively perpetuate white primaries. (As the Tampa Bay Times notes, Florida was “a leading innovator of discriminatory barriers to voting.”)

Before his death, Moore’s efforts in the state helped increase the number of black voters by more than 100,000, according to the Moore Cultural Complex, a figure sure to catch the attention of influential politicians.

But success was a risky proposition. “Moore was coming into a situation in Central Florida where there was a lot of Klan activity, there were a lot of Klansman who had positions in government, and it was a very tenuous time for civil rights,” says Brotemarkle. “People were openly being intimidated and kept away from the polls, and Moore worked diligently to fight that.”

Moore was willing to risk much more than his job. He first became involved in anti-lynching efforts after three white men kidnapped 15-year-old Willie James Howard, bound him with ropes and drowned him in a river for the “crime” of passing a note to a white girl in 1944. The perpetual inaction in cases like Howard’s, in which no one was arrested, tried, or convicted, spurred Moore to effect change. In a 1947 letter to Florida’s congressional delegation, Moore wrote “We cannot afford to wait until the several states get ‘trained’ or ‘educated’ to the point where they can take effective action in such cases. Human life is too valuable for more experimenting of this kind. The Federal Government must be empowered to take the necessary action for the protection of its citizens.”

Moore letters show a polite, but persistent, push for change. His scholarly nature obscured the profound courage it took to stand up to the hostile forces around him in Florida. Those who knew him recall a quiet, soft-spoken man. “The fiery from the pulpit speech? That was not Harry T. Moore. He was much more behind the scenes, but no less aggressive. You can see it from his letters that he was every bit as brave,” says Brotemarkle.

Two years before his death, Moore placed himself in harm’s way in the most prominent manner yet with his involvement in the Groveland Four incident. The men had been accused of raping a white woman; a mob went to drag them from jail and not finding them there, burned and shot into nearby black residents’ homes. After their arrest, conviction by an all-white jury was practically a foregone conclusion, despite attorneys’ assertions that the defendants’ confessions were physically coerced. The case also pitted Moore against Sherriff Willis McCall, who was investigated numerous times in his career for misconduct related to race.

While transporting two of the suspects, McCall shot them, killing one. McCall claimed he had been attacked, but the shootings elicited furious protest. All this took place against the backdrop of the ongoing legal battle—eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered a re-trial, which again ended in the conviction of the surviving suspect, who was represented by Thurgood Marshall. (In recent years, Florida has posthumously pardoned and apologized to all four of the accused).

Moore wrote repeatedly to Governor Fuller Warren, methodically dismantling McCall’s claims. He admonished Warren that “Florida is on trial before the rest of the world,” calling on him to remove the officers involved in the shooting. He closed with a reminder that “Florida Negro citizens are still mindful of the fact that our votes proved to be your margin of victory in the [runoff election in] 1948. We seek no special favors; but certainly we have a right to expect justice and equal protection of the laws even for the humblest Negro. Shall we be disappointed again?”

Compounding Moore’s woes, just weeks after the shooting of the Groveland suspects and weeks before his own death, he lost his job at the NAACP. Moore had clashed with the organization’s national leadership for his forward political involvement and disagreements over fundraising. It was a severe blow, but he continued his commitment to the work—albeit now on an unpaid basis.

During the fall of 1951, Florida saw a rash of religious and racial violence. Over a three-month period, multiple bombs had hit Carver Village, a housing complex in Miami leasing to black tenants, in what was likely the work of the KKK; a synagogue and Catholic church were also menaced. “As dark shadow of violence has drifted across sunny Florida—cast by terrorist who blast and kill in the night,” the Associated Press reported days after the Christmas bombing. If lesser known black residents were targeted, then Moore’s prominence meant his situation was especially perilous.

“Moore ruffled a lot of feathers, and there was a large population of Florida that didn’t want to see the type of change that he was part of,” says Brotemarkle.

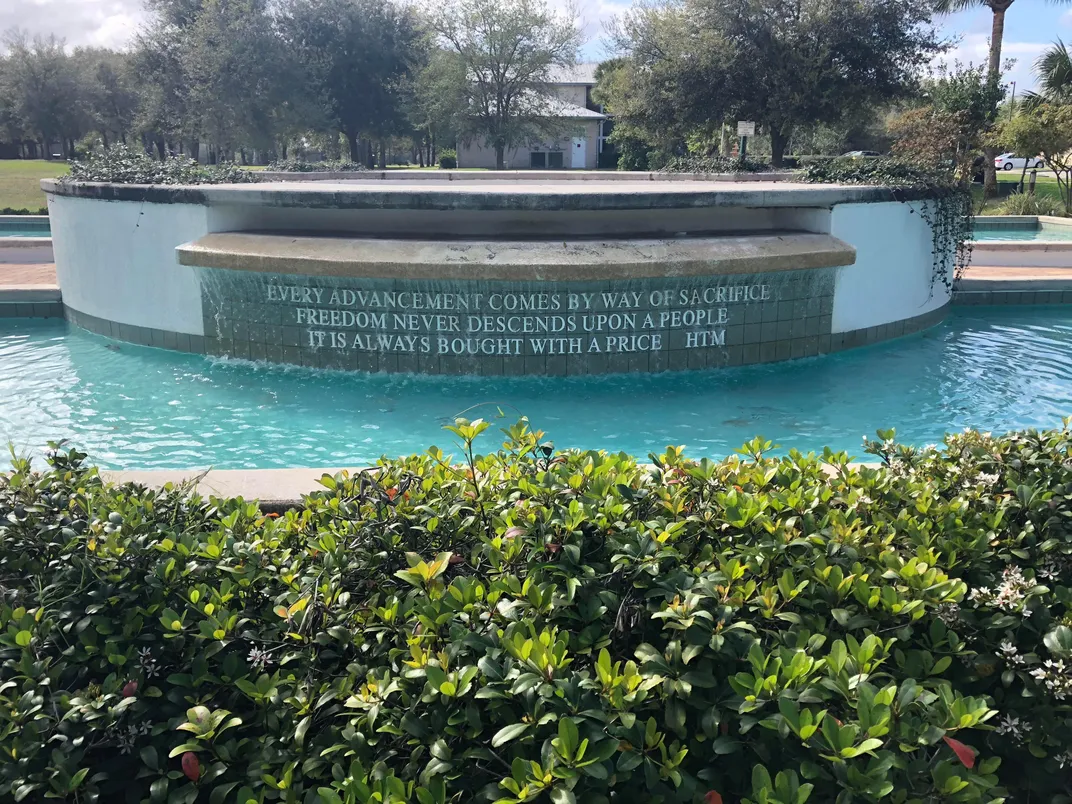

“I tried to get him to quit the N.A.A.C.P., thinking something might happen to him some day,” Rosa Moore told a reporter after the bombing. “But he told me, ‘I’m trying to do what I can to elevate the Negro race. Every advancement comes by the way of sacrifice, and if I sacrifice my life or health I still think it is my duty for my race.”

News of Moore’s Christmas night death made headlines across the country. Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt expressed her sadness. Governor Warren called for a full investigation but clashed with NAACP executive secretary Walter White, who accused the governor of not doing enough. Warren said White “has come to Florida to try to stir up strife” and called him a “hired Harlem hatemonger.”

While Moore may have been out of favor with the NAACP’s national leadership shortly before his death, he was venerated soon after. In March of 1952, the NAACP held a fundraising gala in New York City, featuring the “Ballad of Harry T. Moore,” written by poet Langston Hughes. His name was a rallying cry at numerous events.

“The Moore bombings set off the most intense civil rights uproar in a decade,” writes Ben Green in Before His Time: The Untold Story of Harry T. Moore, America’s First Civil Rights Martyr. “There had been more violent racial incidents…but the Moore bombing was so personal, so singular – a man and his wife blown up in their home on Christmas Day – that it became a magnifying glass to focus the nation’s revulsion.”

While the publicity helped galvanize awareness for civil rights on a national level, the assassination soon had a chilling effect on voter registration in Florida. “People were petrified, they were scared,” says Mallard. The KKK “terrorized you, they killed you, they lynched you, they scared you. They did all that to shut you up.”

Meanwhile Harriette Moore remained hospitalized for nine days, dying from her injuries one day after her husband’s funeral. “There isn't much left to fight for. My home is wrecked. My children are grown up. They don't need me. Others can carry on," she had told a reporter in a bedside interview. Harriette’s discouragement was palpable, after years of facing the same threats side by side with Harry. “She adored her husband,” says Mallard.

The crime has never been definitively solved, despite commitments from notorious FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover in the bombing’s aftermath and from Florida Governor Charlie Crist in the mid-2000s. After almost 70 years, the identity of the killer or killers may never be pinpointed, but those who have studied Moore’s life and the multiple investigations of the case are confident it was the work of the KKK.

“As the movement’s ranks swelled and the battle was carried to Birmingham, Nashville, Tallahassee, Little Rock, Greensboro and beyond, the unsolved murders of Harry and Harriette Moore, still hanging in limbo, were forgotten,” Green writes. “For Evangeline and Peaches Moore, the pain and heartache never ceased. The murderers of their parents still walked the streets, and no one seemed to care.”

Moore’s life and death underscore that not all heroes become legends. Today cities like Selma, Montgomery and Memphis—not Mims—evoke images of the Civil Rights struggle. Moore worked for almost two decades without the weight of national outrage behind him. No television cameras documented the brutal violence or produced the images needed to appall Americans in other states. The Maya Lin-designed Civil Rights Memorial situated across the street from the Southern Poverty Law Center’s office in Montgomery, Alabama, recognizes martyrs from 1955 until Martin Luther King Jr.’s death in 1968. That was 17 years after the Moores were killed.

“When you talk about the contemporary civil rights movement, [people] look at the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 as kind of the starting place for the timeline, and while that can be seen as true in a lot of ways, it overlooks a lot of activity that led up to that,” says Brotemarkle.

Nonetheless Moore’s work and legacy helped lay the groundwork for the expansion of civil rights onto the national platform, and Moore has received some belated recognition in recent decades. The Moore Cultural Complex in Mims welcomes visitors to a replica of their home, rebuilt on the original property. Several of their personal effects are on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, D.C.

In looking back at Moore’s life and work, it is abundantly clear he was never motivated by name recognition in the first place. Moore’s goal was singular - his daughter would later remember him saying before his death that “I have endeavored to help the Negro race and laid my life on the altar.”