Victorian Womanhood, in All Its Guises

Frances Benjamin Johnston’s self-portraits show a woman was never content playing just one role

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Indelible-Frances-Benjamin-Johnston-self-portrait-631.jpg)

Frances Benjamin Johnston made her name as a photographer in the 1890s, taking portraits of the political elite in Washington, D.C.—society hostesses such as Phoebe Hearst, and the wives of President Grover Cleveland’s cabinet members. At the same time, she befriended artists and other outsiders, hosted costume balls in her studio and traveled the country unescorted. Among the 20,000-odd prints she donated to the Library of Congress in 1947—including not only her portraiture, but also a substantial body of photojournalism—are the two self-portraits on these pages.

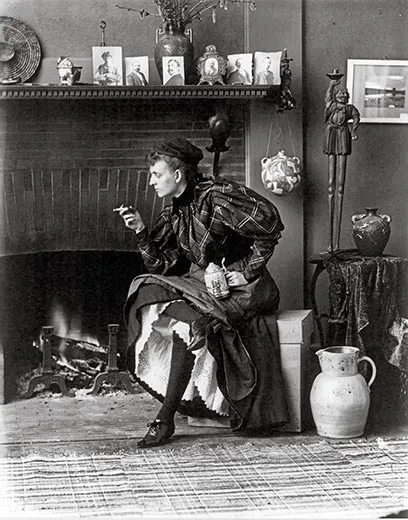

One shows her as a bohemian: holding a cigarette and a beer stein, crossing her legs like a man and revealing her petticoats, leaning aggressively forward, as if in mid-conversation (or confrontation). The photograph, taken around 1896, is self-consciously assertive—“She would not have actually sat that way and done all of those things at one time,” writes Laura Wexler, a professor of American studies at Yale University. The portrait seems to play with the Victorian assumption that unconventional women were somehow “masculine.” By ironic contrast, there’s the undated self-portrait showing her full face, in fur and beribboned hat, her gloved hand occupied in the delicate support of her chin. This lady is proper—and yet she, too, seems to toy with the conventions on display. As Johnston’s biographer Bettina Berch points out, these self-portraits “show viewers there was more than one woman, more than one consciousness, behind the surface they saw.”

These two self-portraits, along with several others, including some in which she wears men’s clothes, were not widely circulated in Johnston’s lifetime. Yet they define two poles of Victorian womanhood. While we might assume that women of Johnston’s time were forced to choose one role or the other, she made a career out of playing many (much as contemporary, role-playing photographer Cindy Sherman would do a century later).

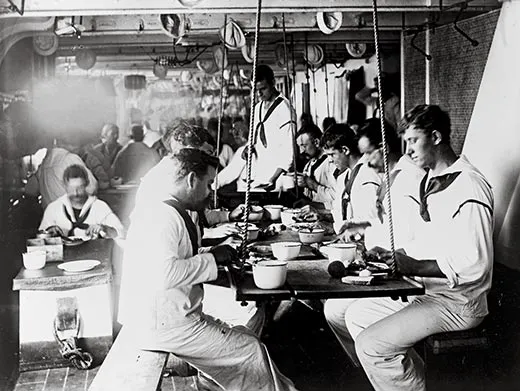

Johnston was born, in 1864, without wealth but with good connections: her father, Anderson Johnston, was head bookkeeper in the Treasury Department, and her mother, Frances Antoinette Johnston, was a Washington correspondent for the Baltimore Sun. They supported their only child’s interest in art, sending her to Paris to study painting. Returning to Washington in 1885, Johnston, then 21, set out to support herself, first as a magazine illustrator and later as a freelance photographer. Her commissions ranged from taking pictures of coal miners underground to documenting educational institutions, such as the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University), founded to educate former slaves. Her photographs of schools were displayed at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1900 as evidence of America’s progress in education. Toward the end of her career she turned to photographing gardens and Southern architecture, preserving views of many antebellum buildings that have since been razed.

While Johnston was running her studio in Washington, feminist campaigns to secure the vote and other rights were encouraging women to break out of their domestic roles. In 1897, she published an article in the Ladies’ Home Journal urging women to consider photography as a means of supporting themselves. “To an energetic, ambitious woman with even ordinary opportunities, success is always possible,” she wrote, adding that “hard, intelligent and conscientious work seldom fails to develop small beginnings into large results.” Johnston also used her influence to help other American female artists—for example, arranging exhibits of their work for the 1900 Paris Exposition. Her portraits of Susan B. Anthony, taken that same year, capture the stoic determination that the feminist leader needed—for half a century—to hold together the competing groups working toward women’s suffrage. And yet there is no evidence that Johnston ever participated in a feminist campaign.

She maintained her independence, financially and artistically, till she died, in 1952, at age 88. Wexler writes that Johnston was one of several women who “held a very significant place in American photography at the turn of the century and then were ‘lost’ to history.” Now, 90 years after the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote, Johnston’s bohemian artist still urges women forward at the same time her proper Victorian lady reminds us all to look back at what we have achieved. In both cases, the images show a woman using every angle to forge a new identity for herself and for the legions of women who would follow her.

Victoria Olsen last wrote for the magazine on Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits.