The time stamp on the first picture I made after the blast, out of focus and full of dust, says 11:26:06 a.m.

A few pictures later, at 11:27:41, team leader Cpl. Eric Hopp has a tourniquet on Cpl. Manuel Jimenez’s arm. Only about 1 minute and 35 seconds, from blast to stopping the bleed. I remember the force of the explosion and how it made my shoulders seize and then I couldn’t hear. How I looked back and forth, trying to figure out where it came from until I realized it was right behind me. I remember I wheeled around and saw a curtain of white and I felt Corporal Hopp running past me. I pushed the button and squeezed off a couple of pictures, but the camera wouldn’t focus. It felt like someone slowly turned up the volume in my head, and then I could hear Jimenez screaming. I ran into the white dust until I saw him on the ground, writhing, and Corporal Hopp above him, saving him.

The war in Afghanistan took Cpl. Manuel Jimenez’s left arm. But in the eight years since we shared that terrible day, he’s made it clear that an arm is all he let it take from him.

The mechanics of embedded photojournalism mean that you end up closer to some guys, both physically and otherwise. You go out on patrol, you walk kind of spread out, someone is assigned to watch out for you in case there is contact. You end up making a lot of pictures of the guys in front of and behind you. I arrived at a small firebase in Marjah, in southern Afghanistan’s Helmand Province, at the end of July 2010. I had spent time in the field with a few different military units, but never met a group of soldiers or Marines as capable as First Platoon, Fox Company, 2-6 Marines. I went out with Jimenez’s fire team on a handful of patrols my first few days and he was usually just behind me.

Soldiers on deployment sometimes seem desperate to fill shoes they haven’t quite grown into yet. Manny was different. There was no bravado, he was funny in a cynical, deadpan way, like he’d seen it all even though he was only 22. He was friendly but reserved, never boastful, quiet but always in the middle of things. He tended to lead from behind.

As we turned for home that afternoon, I was walking about 25 feet in front of him, keeping good dispersion. An improvised explosive device buried in the road exploded right as Manny walked by it. It blew apart his arm, filled him with shrapnel and almost severed his carotid artery. Corporal Hopp and other Marines wrapped what was left of his arm and carried him over a canal. They shielded him from the dust and rocks when the medevac came. They loaded him onto the helicopter, watched it carry him away and went on with their deployment. They were back on patrol the next day.

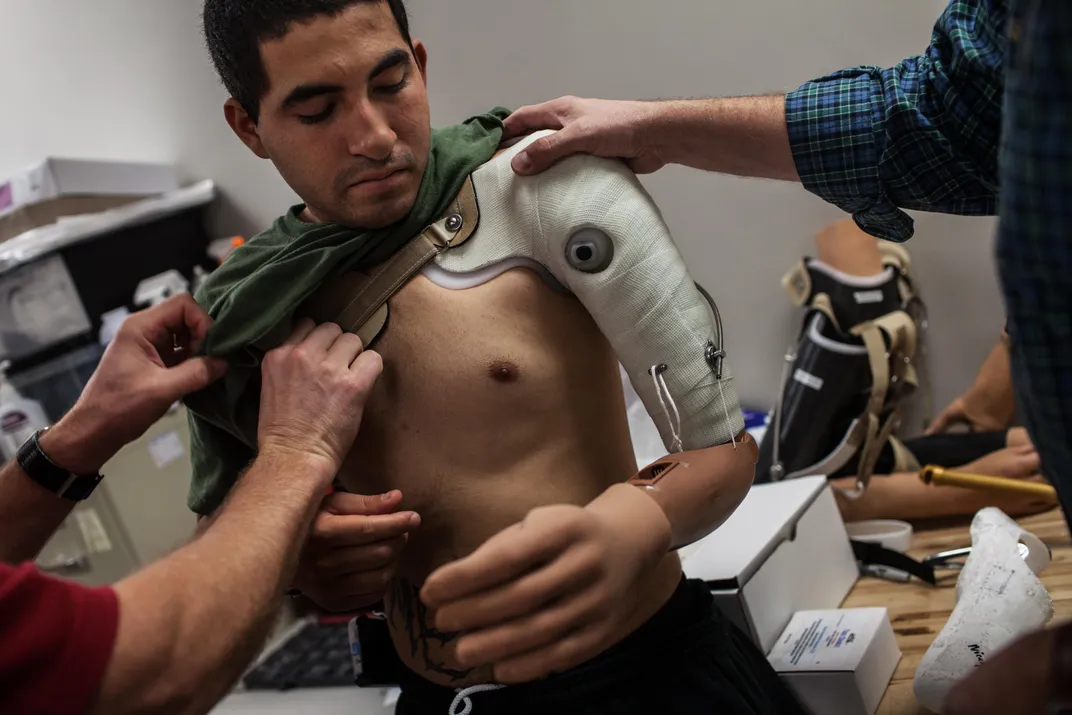

I photographed through the summer in Afghanistan, got back to the United States, and drove out to Bethesda, Maryland. Manny was at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, where he was recovering from another of his innumerable surgeries. Over the next few months, I returned a few times to see his recovery at the Military Advanced Training Center, or MATC, the rehab unit. Manny worked out there with his fellow amputees. The MATC was like a big gym with what looked at first glance like incomplete men, all of them missing one, two, sometimes four limbs.

Their wives or mothers, sometimes both, sat with them, looking confused and tired. I had never seen so much painful, quiet resolve in one place in my life. Manny and the other guys pushed themselves, sweated and winced through the hurt and frustration. They tried out new prostheses, they balanced on parallel bars, caught balls and lifted weights. They were like self-assembling puzzles, trying to rebuild new versions of themselves with some of their pieces missing. Every time I left that place I felt physically aware of my own limitations and unsure of my own grit.

I started going up to see Manny and his family in their home in New Britain, Connecticut, where he grew up in public housing. He has a big, loving, raucous Puerto Rican family—his brothers and sisters, his nephews and nieces and cousins, all of them seem to orbit his mom, Ana Mendoza, who is quick with a hug and a plate for dinner.

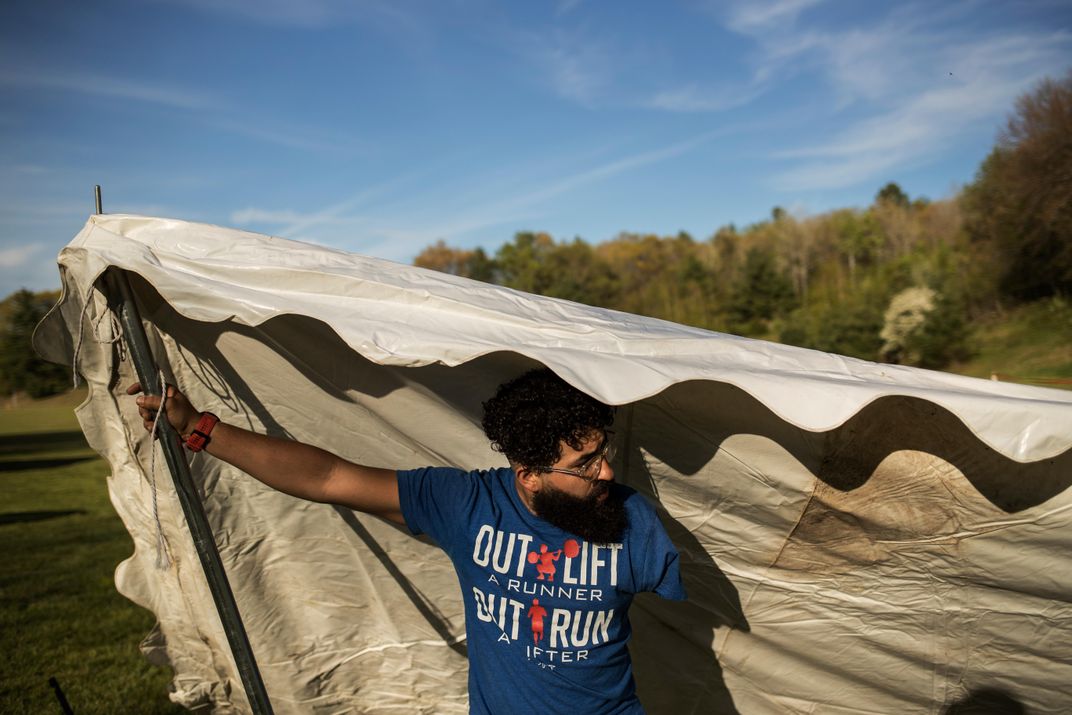

On Veterans Day, I went with Manny to visit his high school, when he said a few words before the football game, wearing his dress blues, his prosthetic hand rotating awkwardly in the cold. I showed up for a family picnic for the Fourth of July, where he tossed his little nephews in the inflatable pool with his one good arm. I hung out with him at a road race, a benefit for veterans, where he helped register the runners and hand out awards. Like a lot of wounded warriors, Manny embraced extreme athletics to fight his way to recovery. He tried a few things—cycling, swimming, golf—and settled on distance running. He’s run marathons all over the United States and Europe, always trying to beat his personal record.

After the Marine Corps, after Walter Reed, Manny spent time volunteering in New York after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, then stayed for a while in Florida with his cousins, before he settled back into his life in Connecticut.

A fortuitous introduction at a race connected him with Hope for the Warriors and Purple Heart Warriors—nonprofits providing mortgage assistance and custom-built houses for wounded veterans—and they got him his own place in the town of Glastonbury. He completed his B.A. in business, and started work as an analyst at a Fortune 500 company. He has reached past the blast, the disappointment of having to leave the Corps, and the loss of his arm.

This spring I went up to see Manny and accompany him on a “Hike to Remember,” an event that he and the Marine Corps League Detachment 40, a local veterans group, organized. They walked 14 miles around town to raise awareness for the epidemic of veteran suicides. The year they introduced the event, in 2012, they had nine participants. This year there were 210. I saw him coordinate, help with the event, rev up the tired and the slow-moving among the group. Two of his buddies from his unit, Jacob Rivera and Cory Loudenback, came to walk with him. They marched and hung out late, catching up. Manny looks out for these guys, he keeps in touch, he reaches out when things become suspiciously quiet. Manny has dealt with PTSD himself, but he’s learned to keep it in check. His sister Jahaira refused to let him isolate himself. “You can spiral wicked fast,” he says. “She was like, ‘You should go talk,’ and then she would always make me go to events.”

This year he and a buddy went to a training to help those who’ve suffered from military sexual trauma. He uses what he learned to help a friend who suffered a horrifying sexual assault as a soldier. They met running in races together, and he talks to her about once a week and attends her competitions when he can—he keeps track, makes sure she’s okay.

One afternoon after the hike, we sat down and talked about that day in Afghanistan. Weirdly enough, after all these years, we hadn’t ever really gone over it together. Manny kicked back on his couch, his chocolate lab Striker draped over him. At first, he said, so much of what happened was a blur—he suffered a traumatic brain injury—but over the years more has come back to him. “I remember getting blown up,” he said. “I flew, I remember my arm and yelling that my arm was f-----. I can’t see out of my eye. Then, Hopp was there.”

We shared the things we remembered, and marveled over the things we never knew. He told me about the chopper. The pain was excruciating, but the morphine injections they had already given him hadn’t knocked him out. “I was still conscious and they didn’t understand why,” he laughs. “I was still talking. They hit me with another pen right in the middle of the chest,” and the next thing he knew, he was in Germany, on his way home.

After we talked, we went outside and tossed a ball for Striker. Soon after, I packed the car, we said our goodbyes, and I drove away. It’s a strange thing. You spend such a short period of time with these guys, in such an extreme place, and then it’s over, and you go home and they finish their deployments.

I think I kept up with Manny because I wanted to see what happens when they get back from “over there” and become us again. And probably because I wanted to hang onto that day together. It had been so close for him, and he had made it, and I didn’t want to let that go.

:focal(3423x1149:3424x1150)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/9a/d49a45ef-b15d-420e-bd02-3b9107c3c5fc/janfeb2019_i05_photooneied.jpg)