We Had No Idea What Alexander Graham Bell Sounded Like. Until Now

Smithsonian researchers used optical technology to play back the unplayable records

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Clear-as-a-Bell-record-631.jpg)

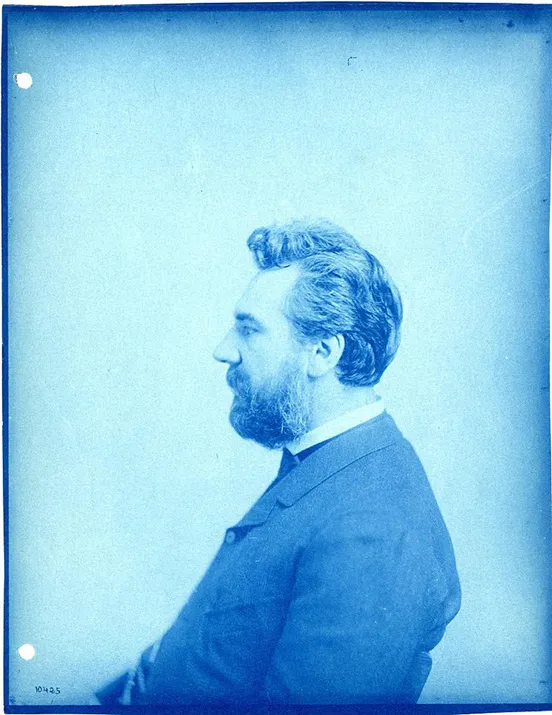

During the years I spent in the company of Alexander Graham Bell, at work on his biography, I often wondered what the inventor of the world’s most important acoustical device—the telephone—might have sounded like.

Born in Scotland in 1847, Bell, at different periods of his life, lived in England, then Canada and, later, the Eastern Seaboard of the United States. His favorite refuge was Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, where he spent the summers from the mid-1880s on. In his day, 85 percent of the population there conversed in Gaelic. Did Bell speak with a Scottish burr? What was the pitch and depth of the voice with which he loved to belt out ballads and music hall songs?

Someone who knew that voice was his granddaughter, Mabel Grosvenor, a noted Washington, D.C. pediatrician who retired in 1966. In 2004, I met with Dr. Mabel, as she was known in the family, when she was 99 years old—clearheaded, dignified and a bit fierce. I inquired whether her grandfather had an accent. “He sounded,” she said firmly, “like you.” As a British-born immigrant to Canada, my accent is BBC English with a Canadian overlay: It made instant sense to me that I would share intonations and pronunciations with a man raised in Edinburgh who had resided in North America from the age of 23. When Dr. Mabel died in 2006, the last direct link with the inventor was gone.

Today, however, a dramatic application of digital technology has allowed researchers to recover Bell’s voice from a recording held by the Smithsonian—a breakthrough announced here for the first time. From the 1880s on, until his death in 1922, Bell gave an extensive collection of laboratory materials to the Smithsonian Institution, where he was a member of the Board of Regents. The donation included more than 400 discs and cylinders Bell used as he tried his hand at recording sound. The holdings also documented Bell’s research, should patent disputes arise similar to the protracted legal wrangling that attended the invention of the telephone.

Bell conducted his sound experiments between 1880 and 1886, collaborating with his cousin Chichester Bell and technician Charles Sumner Tainter. They worked at Bell’s Volta Laboratory, at 1221 Connecticut Avenue in Washington, originally established inside what had been a stable. In 1877, his great rival, Thomas Edison, had recorded sound on embossed foil; Bell was eager to improve the process. Some of Bell’s research on light and sound during this period anticipated fiber-optic communications.

Inside the lab, Bell and his associates bent over their pioneering audio apparatus, testing the potential of a variety of materials, including metal, wax, glass, paper, plaster, foil and cardboard, for recording sound, and then listening to what they had embedded on discs or cylinders. However, the precise methods they employed in early efforts to play back their recordings are lost to history.

As a result, says curator Carlene Stephens of the National Museum of American History, the discs, ranging from 4 to 14 inches in diameter, remained “mute artifacts.” She began to wonder, she adds, “if we would ever know what was on them.”

Then, Stephens learned that physicist Carl Haber at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California, had succeeded in extracting sound from early recordings made in Paris in 1860. He and his team created high-resolution optical scans converted by computer into an audio file.

Stephens contacted Haber. Early in 2011, Haber, his colleague physicist Earl Cornell and Peter Alyea, a digital conversion specialist at the Library of Congress, began analyzing the Volta Lab discs, unlocking sound inaccessible for more than a century. Muffled voices could be detected reciting Hamlet’s soliloquy, sequences of numbers and “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

In autumn 2011, Patrick Feaster, an Indiana University sound-media historian, aided by Stephens, compiled an exhaustive inventory of notations on the discs and cylinders—many scratched on wax and all but illegible. Their scholarly detective work led to a tantalizing discovery. Documents indicated that one wax-and-cardboard disc, from April 15, 1885—a date now deciphered from a wax inscription—contained a recording of Bell speaking.

On June 20, 2012, at the Library of Congress, a team including Haber, Stephens and Alyea was transfixed as it listened to the inventor himself : “In witness whereof—hear my voice, Alexander Graham Bell.”

In that ringing declaration, I heard the clear diction of a man whose father, Alexander Melville Bell, had been a renowned elocution teacher (and perhaps the model for the imperious Prof. Henry Higgins, in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion; Shaw acknowledged Bell in his preface to the play).

I heard, too, the deliberate enunciation of a devoted husband whose deaf wife, Mabel, was dependent on lip reading. And true to his granddaughter’s word, the intonation of the British Isles was unmistakable in Bell’s speech. The voice is vigorous and forthright—as was the inventor, at last speaking to us across the years.